Eflornithine

-Eflornithin_Structural_Formulae_V.1.svg.png) | |

|

Enantiomer R of eflornithin (top) and S-eflornithin (middle) | |

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

|---|---|

| (RS)-2,5-diamino-2-(difluoromethyl)pentanoic acid | |

| Clinical data | |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | monograph |

| Licence data | EMA:Link, US FDA:link |

| |

| |

|

Intravenous (discontinued) Dermal | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability |

100% (Intravenous) Negligible (Dermal) |

| Metabolism | Not metabolised |

| Half-life | 8 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

|

70052-12-9 | |

| D11AX16 P01CX03 | |

| PubChem | CID 3009 |

| ChemSpider |

2902 |

| UNII |

ZQN1G5V6SR |

| KEGG |

D07883 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:41948 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL830 |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C6H12F2N2O2 |

| 182.2 g/mol | |

|

SMILES

| |

| |

| | |

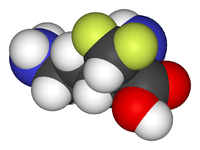

Eflornithine (α-difluoromethylornithine or DFMO) is a drug found to be effective in the treatment of facial hirsutism [1] (excessive hair growth) as well as in African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness).[2] Eflornithine hydrochloride cream for topical application is meant for women suffering from facial hirsutism. Eflornithine for injection against sleeping sickness is manufactured by Sanofi Aventis and sold under the brand name Ornidyl in the USA.[3] Both are prescription drugs.

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[4]

Mechanism of action

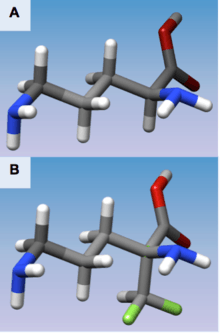

Schematic of mechanism of action

(A) 3D structure of L-Ornithine

(B) 3D structure of Eflornithine. This molecule is similar to the structure of L-Ornithine, but its alpha-difluoromethyl group allows interaction with Cys-360 in the active site

Derived from Poulin, R., et al. "Mechanism of the irreversible inactivation of mouse ornithine decarboxylase by alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Characterization of sequences at the inhibitor and coenzyme binding sites." Journal of Biological Chemistry 267.1 (1992): 150-158.

Mechanism of action description

Eflornithine is a “suicide inhibitor,” irreversibly binding to Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and preventing the natural substrate ornithine from accessing the active site (Figure 1). Within the active site of ODC, eflornithine undergoes decarboxylation with aid of the cofactor pyridoxal 5’-phosphate (PLP). Because of its additional difluoromethyl group in comparison to ornithine, eflornithine is able to bind to a neighboring Cys-360 residue, permanently remaining fixated within the active site.

During the reaction, eflornithine’s decarboxylation mechanism is analogous to that of ornithine in the active site, where transimination occurs with PLP followed by decarboxylation. During the event of decarboxylation, the fluoride atoms attached to the additional methyl group pull the resulting negative charge from the release of carbon dioxide, causing a fluoride ion to be released. In the natural substrate of ODC, the ring of PLP accepts the electrons that result from the release of CO2.

The remaining fluoride atom that resides attached to the additional methyl group creates an electrophilic carbon that is attacked by the nearby thiol group of Cys-360, allowing eflornithine to remain permanently attached to the enzyme following the release of the second fluoride atom and transimination.

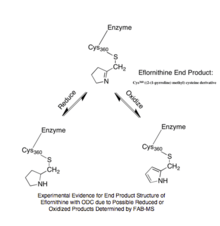

Evidence for mechanism of action

Experimental Evidence for Eflornithine End Product[5]

The reaction mechanism of Trypanosoma brucei’s ODC with ornithine was characterized by UV-VIS spectroscopy in order to identify unique intermediates that occurred during the reaction. The specific method of multiwavelength stopped-flow spectroscopy utilized monochromatic light and fluorescence to identify five specific intermediates due to changes in absorbance measurements.[6] The steady-state turnover number, kcat, of ODC was calculated to be 0.5 s-1 at 4 °C.[6] From this characterization, the rate-limiting step was determined to be the release of the product putrescine from ODC’s reaction with ornithine. In studying the hypothetical reaction mechanism for eflornithine, information collected from radioactive peptide and eflornithine mapping, high pressure liquid chromatography, and gas phase peptide sequencing suggested that Lys-69 and Cys-360 are covalently bound to eflornithine in T. Brucei ODC’s active site.[5] Utilizing fast-atom bombardment mass spectrometry (FAB-MS), the structural conformation of eflornithine following its interaction with ODC was determined to be S-((2-(1-pyrroline-methyl) cysteine, a cyclic imine adduct. Presence of this particular product was supported by the possibility to further reduce the end product to S-((2-pyrrole) methyl) cysteine in the presence of NaBH4 and oxidize the end product to S-((2-pyrrolidine) methyl) cysteine (Figure 2).[5]

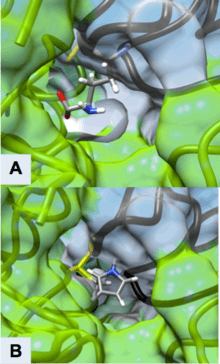

Eflornithine in the active site

Active Site of ODC Formed by Homodimerization (Green and White Surface Structures)

(A) Ornithine in the Active Site of ODC, Cys-360 highlighted in yellow

(B) Product of Eflornithine Decarboxylation bound to Cys 360 (highlighted in yellow). The pyrroline ring blocks ornithine from entering the active site

Derived from Grishin, Nick V., et al. "X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: the native structure and the structure in complex with α-difluoromethylornithine." Biochemistry 38.46 (1999): 15174-15184. PDB ID: 2TOD

Eflornithine’s suicide inhibition of ODC physically blocks the natural substrate ornithine from accessing the active site of the enzyme (Figure 3). There are two distinct active sites formed by the homodimerization of ornithine decarboxylase. The size of the opening to the active site is approximately 13.6 Å. When these openings to the active site are blocked, there are no other ways through which ornithine can enter the active site. During the intermediate stage of eflornithine with PLP, its position near Cys-360 allows an interaction to occur. As the phosphate of PLP is stabilized by Arg 277 and a Gly-rich loop (235-237), the difluoromethyl group of eflornithine is able to interact and remain fixated to both Cys-360 and PLP prior to transimination. As shown in the figure, the pyrroline ring interferes with ornithine’s entry (Figure 4). Eflornithine will remain permanently bound in this position to Cys-360. As ODC has two active sites, two eflornithine molecules are required to completely inhibit ODC from ornithine decarboxylation.

Figure 4

(A) Magnified Active Site of Ornithine Decarboxylase with PLP-Eflornithine-Cys-360 intermediate complex

(B) Important residues in ODC active site with intermediate state of Eflornithine (black) and PLP (red) complex[5]

Derived from Grishin, Nick V., et al. "X-ray structure of ornithine decarboxylase from Trypanosoma brucei: the native structure and the structure in complex with α-difluoromethylornithine." Biochemistry 38.46 (1999): 15174-15184. PDB ID: 2TOD

History

Eflornithine was initially developed for cancer treatment at Merrell Dow Research Institute in the late 1970s, but, while having little use in treating malignancies, it was found to be highly effective in reducing hair growth,[1] as well as in treatment of African trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness),[2] especially the West African form (Trypanosoma brucei gambiense).

Hirsutism

In the 1980s, Gillette was awarded a patent for the discovery that topical application of eflornithine HCl cream inhibits hair growth. In the 1990s, Gillette conducted dose-ranging studies with eflornithine in hirsute women that demonstrated that the drug slows the rate of facial hair growth. Gillette then filed a patent for the formulation of eflornithine cream. In July 2000, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) granted a New Drug Application for Vaniqa. The following year, the European Commission issued its Marketing Authorisation. Today, Vaniqa is marketed by Almirall in Europe, Menarini in Australia, Triton in Canada, Medison in Israel and SkinMedica in the USA.[7]

Sleeping sickness treatment

The drug was registered for the treatment of gambiense sleeping sickness on November 28, 1990.[8] However, in 1995 Aventis (now Sanofi-Aventis) stopped producing the drug, whose main market was African countries, because it didn't make a profit.[9]

In 2001, Aventis (now Sanofi-Aventis) and the WHO formed a five-year partnership, during which more than 320,000 vials of pentamidine, over 420,000 vials of melarsoprol, and over 200,000 bottles of eflornithine were produced by Sanofi-Aventis, to be given to the WHO and distributed by the association Médecins sans Frontières (also known as Doctors Without Borders)[10][11] in countries where the sleeping sickness is endemic.

According to Médecins sans Frontières, this only happened after "years of international pressure", and coinciding with the period when media attention was generated because of the launch of another eflornithine-based product (Vaniqa, geared to prevention of facial-hair in women),[9] while its life-saving formulation (the one against sleeping sickness) was not being produced.

From 2001 (when production was restarted) through 2006, 14 million diagnoses were made. This greatly contributed to stemming the spread of sleeping sickness, and to saving nearly 110,000 lives. This changed the epidemiological profile of the disease, meaning that eliminating it altogether can now be envisaged.[10]

Clinical use

Facial hirsutism in women

Hirsutism affects between 5-15% of all women across all ethnic backgrounds.[12] Depending on the definition and the underlying data, estimates indicate that approximately 40% of women have some degree of unwanted facial hair.[13]

Hirsutism is usually the result of an underlying adrenal, ovarian, or central endocrine imbalance.[13] Hirsutism is a commonly presenting symptom in dermatology, endocrinology and gynaecology clinics, and one that is considered to be the cause of much psychological distress and social difficulty.[14] Facial hirsutism often leads to the avoidance of social situations and to symptoms of anxiety and depression.[15]

Vaniqa is indicated for treatment of facial hirsutism in women.[16] It is the only topical prescription treatment that slows the growth of facial hair.[17] It is applied in a thin layer twice daily, a minimum of eight hours between applications. In clinical studies with Vaniqa, 81% percent of women showed clinical improvement after twelve months of treatment.[18] Positive results were seen after eight weeks.[18]

Vaniqa and laser treatment have complementary mechanisms of action.[19] As Vaniqa does not affect hair diameter, it does not decrease the efficacy of simultaneous or subsequent laser therapy.[20] Synergies between the two treatment methods lead to faster and better end results.[19]

Vaniqa treatment significantly reduces the psychological burden of facial hirsutism.[15]

Sleeping sickness

Human African trypanosomiasis (HAT) is a parasitic disease spread by the tsetse fly. It is found only in subtropical and equatorial Africa. In 1995, the WHO estimated that 300,000 people were afflicted with the disease. In its 2001 report, the WHO set the figure of people at risk of infection at 60 million, of which only 4 to 5 million had access to any kind of medical monitoring. In 2006, the WHO estimated that about 70,000 people could have the disease, which, if left untreated, is always fatal.[10][21]

Sleeping sickness is treated with pentamidine or suramin (depending on subspecies of parasite) delivered by intramuscular injection in the first phase of the disease, and with melarsoprol and eflornithine in intravenous injection (50 mg/kg every six hours for 14 days [7]) in the second phase of the disease.[10]

General importance and effectiveness

Clinical trials and effectiveness for human African trypanosomiasis

A 2008 cohort study in southern Sudan examined the effectiveness of eflornithine for 1055 patients diagnosed with second stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense. Results indicated that of the 924 patients whose final outcome was known or who were seen during follow up visits, “16 (1.7%) died during treatment, 70 (7.6%) relapsed, 15 (1.6%) died of disease during follow-up, 403 (43.6%) were confirmed cured, and 420 (45.5%) were probably cured (favorable progression until the last assessment).” [22] Children were also able to tolerate higher doses than previously recorded, but no advantage was observed.

Eflornithine is also effective in combination with other drugs, such as melarsoprol and nifurtimox. A study in 2005 compared the safety of eflornithine alone to melarsoprol and found eflornithine to be more effective and safe in treating second-stage sleeping sickness.[22] Another randomized control trial in Uganda compared the efficacy of various combinations of these drugs and found that the nifurtimox-eflornithine combination was the most promising first-line theory regimen.[23]

In 2000, the cost for the 14-day regimen was US $500; a price that endemic countries cannot afford.[24] A randomized control trial was conducted in Congo, Côte d'Ivoire, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Uganda to determine if a 7-day intravenous regimen was as efficient as the standard 14-day regimen for new and relapsing cases. The results showed that the shortened regimen was efficacious in relapse cases, but was inferior to the standard regimen for new cases of the disease.[24]

Trypanosome resistance

After its introduction to the market in the 1980s, eflornithine has replaced the other form of treatment, melarsoprol, as the first line medication against Human African trypanosomiasis due to its reduced toxicity to the host.[24] Trypanosoma brucei resistant to eflornithine has been reported as early as the mid-1980s.[24]

The gene TbAAT6, conserved in the genome of Trypanosomes, is believed to be responsible for the transmembrane transporter that brings eflornithine into the cell.[25] The loss of this gene due to specific mutations causes resistance to eflornithine in several trypanosomes.[26] If eflornithine is prescribed to a patient with Human African trypanosomiasis caused by a trypanosome that contains a mutated or ineffective TbAAT6 gene, then the medication will be ineffective against the disease. Resistance to eflornithine has increased the use of melarsoprol despite its toxicity, which has been linked to the deaths of 5% of recipient HAT patients [24]

Revival in chemo preventative therapy

It has been noted that ODC exhibits high activity in tumor cells, promoting cell growth and division, while absence of ODC activity leads to depletion of putrescine, causing impairment of RNA and DNA synthesis. Typically, drugs that inhibit cell growth are considered candidates for cancer therapy, so eflornithine was naturally believed to have potential utility as an anti-cancer agent. By inhibiting ODC, eflornithine inhibits cell growth and division of both cancerous and noncancerous cells.

However, several clinical trials demonstrated minor results.[27] It was found that inhibition of ODC by eflornithine does not kill proliferating cells, making eflornithine ineffective as a chemotherapeutic agent. The inhibition of the formation of polyamines by ODC activity can be ameliorated by dietary and bacterial means because high concentrations are found in cheese, red meat, and some intestinal bacteria, providing reserves if ODC is inhibited [28] Although the role of polyamines in carcinogenesis is still unclear, polyamine synthesis has been supported to be more of a causative agent than merely an associative effect in cancer.[27]

Other studies have suggested that eflornithine can still aid in some chemoprevention by lowering polyamine levels in colorectal mucosa with additional strong preclinical evidence available for application of eflornithine in colorectal and skin carcinogenesis.[27][28] This has made eflornithine a supported chemopreventive therapy specifically for colon cancer in combination with other medications. Several additional studies have found that eflornithine in combination with other compounds decreases the carcinogen concentrations of ethylnitrosourea, dimethylhydrazine, azoxymethane, methylnitrosourea, and hydroxybutylnitrosamine in the brain, spinal cord, intestine, mammary gland, and urinary bladder.[28]

Alzheimer's disease treatment

In 2015, Carol Colton and other researchers at Duke University published findings in the Journal of Neuroscience that difluoromethylornithine was successfully used to treat the symptoms of Alzheimer's disease in mice by blocking the uptake of arginine in immune cells. This uptake process appears necessary to create the amyloid plaque commonly thought to be responsible for the disease's detrimental effects.[29][30]

Available forms and dosage

Vaniqa

Vaniqa is a cream, which is white to off-white in colour. It is supplied in tubes of 30 g and 60 g in Europe.[31] Vaniqa contains 15% w/w eflornithine hydrochloride monohydrate, corresponding to 11.5% w/w anhydrous eflornithine (EU), respectively 13.9% w/w anhydrous eflornithine hydrochloride (U.S.), in a cream for topical administration.

Ornidyl

Ornidyl, intended for injection, is supplied in the strength of 200 mg eflornithine hydrochloride per ml.[32]

Contraindications

Vaniqa

Vaniqa is contraindicated for patients hypersensitive to eflornithine or to any of the excipients.[33]

Throughout clinical trials, data from a limited number of exposed pregnancies indicate that there is no clinical evidence that treatment with Vaniqa adversely affects pregnant women or fetuses.[33]

Ornidyl

Ornidyl’s risk-benefit should be assessed in patients with impaired renal function or pre-existing hematologic abnormalities, as well as those with eighth-cranial-nerve impairment.[34] Adequate and well-controlled studies with Ornidyl have not been performed regarding pregnancy in humans. Eflornithine should only be used during pregnancy if the potential benefit justifies the potential risk to the fetus. However, since African trypanosomiasis has such a high mortality rate if left untreated, treatment with eflornithine may justify any potential risk to the fetus.[34]

Adverse effects/side effects

Eflornithine is not genotoxic; no tumour-inducing effects have been observed in carcinogenicity studies, including one photocarcinogenicity study.[35] No teratogenic effects have been detected.[36]

Topical use

The most frequently reported side effect is acne (7-14%). Other side effects commonly (> 1%) reported are skin problems, such as skin reactions from in-growing hair, hair loss, burning, stinging or tingling sensations, dry skin, itching, redness or rash.[31]

Ornidyl

Most side effects related to systemic use of Ornidyl through injection are transient and reversible by discontinuing the drug or decreasing the dose. Hematologic abnormalities occur frequently, ranging from 10–55%. These abnormalities are dose-related and are usually reversible. Thrombocytopenia is thought to be due to a production defect rather than to peripheral destruction. Seizures were seen in approximately 8% of patients, but may be related to the disease state rather than the drug. Reversible hearing loss has occurred in 30–70% of patients receiving long-term therapy (more than 4–8 weeks of therapy or a total dose of >300 grams); high-frequency hearing is lost first, followed by middle- and low-frequency hearing. Because treatment for African trypanosomiasis is short-term, patients are unlikely to experience hearing loss.[34]

Interactions

Vaniqa

No interaction studies with Vaniqa have been performed.[33]

Ornidyl

Ornidyl may interact with bone marrow depressants and ototoxic medications.[34]

Market

Vaniqa

Vaniqa, granted marketing approval by the US FDA, as well as by the European Commission[7] among others, is currently the only topical prescription treatment that slows the growth of facial hair.[37] Besides being a non-mechanical and non-cosmetic treatment, it is the only non-hormonal and non-systemic prescription option available for women who suffer from facial hirsutism.[16] Vaniqa is marketed by Almirall in Europe, SkinMedica in the USA, Triton in Canada, Medison in Israel, and Menarini in Australia.[7]

Ornidyl

The positive results of the 2001-2006 partnership between Sanofi-Aventis and the WHO in the fight against sleeping sickness motivated and justified the decision taken by the Sanofi-Aventis Group's senior management to continue supporting the WHO at the same level for another five years, 2006-2011.[10]

Synthesis

Much attention has been focused upon the exciting promise of enzyme activated enzyme inhibitors for potential use in therapy. In contrast to the ordinary alkylating agents which are aggressive chemicals in the ground state and, thus, lack specificity in the body and produce many side effects and unwanted toxic actions, the so-called K-cat inhibitors or suicide substrates turn the enzyme's catalytic action against itself. The enzyme first accepts the suicide substrate as though it were the normal substrate and begins to process it at its active site. At this point, it receives a nasty surprise. This intermediate now is not a normal substrate which peacefully undergoes catalytic processing and makes way for another molecule of substrate, but rather is an aggressive compound which attacks the active site itself and inactivates the enzyme. As the suicide substrate is only highly reactive when processed by the enzyme, it achieves specificity through use of the selective recognition features of the enzyme itself and it works out its aggression at the point of generation sparing more distant nucleophiles. Thus, much greater specificity is expected from such agents than from electrophiles which are highly reactive in the ground state.

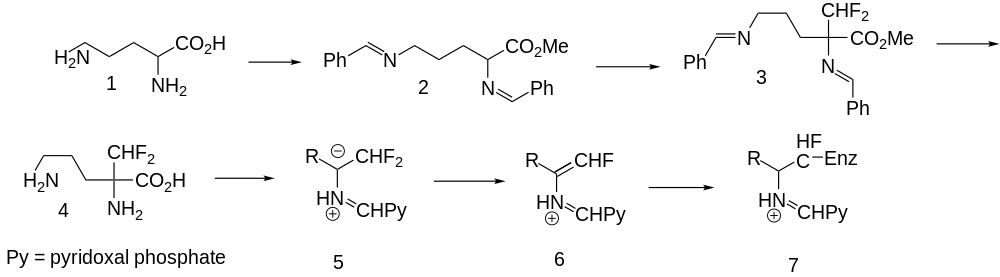

Eflornithine (4) represents such a suicide substrate. Cellular polyamines are widely held to be involved in cellular growth regulation and, in particular, their concentration is needed for accelerated growth of neoplastic cells. The enzyme ornithine decarboxylase catalyzes a rate determining step in cellular polyamine biosynthesis and a good inhibitor ought to have antitumor activity. The synthesis of eflornithine starts with esterification of the amino acid ornithine (1) followed by acid-catalyzed protection of the two primary amino groups as their benzylidine derivatives (2). The acidic proton is abstracted with lithium diisopropylamide and then alkylated with chlorodifluoromethane to give 3. This last is deprotected by acid hydrolysis to give eflornithine (4).[38]

Ornithine decarboxylase is a pyridoxal dependent enzyme. In its catalytic cycle, it normally converts ornithine (1) to putrescine by decarboxylation. If it starts the process with eflornithine instead, the key imine anion (5) produced by decarboxylation can either alkylate the enzyme directly by displacement of either fluorine atom or it can eject a fluorine atom to produce vinylogue 6 which can alkylate the enzyme by conjugate addition. In either case, 7 results in which the active site of the enzyme is alkylated and unable to continue processing substrate. The net result is a downturn in the synthesis of cellular polyamine production and a decrease in growth rate. Eflornithine is described as being useful in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia, as an antiprotozoal or an antineoplastic substance.[38][39]

See also

- Hirsutism

- African trypanosomiasis

- Caracemide

- Avridine

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Wolf JE, Shander D, Huber F, Jackson J, Lin CS, Mathes BM, Schrode K, and the Eflornithine Study Group. Randomized, double-blind clinical evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical eflornithine HCI 13.9% cream in the treatment of women with facial hair. Int J Dermatol 2007 Jan; 46(1): 94-8. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pepin J, Milord F, Guern C, Schechter PJ (1987). "Difluoromethylornithine for arseno-resistant Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness". Lancet 2 (8573): 1431–3. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)91131-7. PMID 2891995.

- ↑ "Ornidyl advanced consumer information". Drugs.com.

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines". World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Poulin, R; Lu, L; Ackermann, B; Bey, P; Pegg, AE (Jan 5, 1992). "Mechanism of the irreversible inactivation of mouse ornithine decarboxylase by alpha-difluoromethylornithine. Characterization of sequences at the inhibitor and coenzyme binding sites.". The Journal of Biological Chemistry 267 (1): 150–8. PMID 1730582.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Brooks, HB; Phillips, MA (Dec 9, 1997). "Characterization of the reaction mechanism for Trypanosoma brucei ornithine decarboxylase by multiwavelength stopped-flow spectroscopy.". Biochemistry 36 (49): 15147–55. doi:10.1021/bi971652b. PMID 9398243.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 "Vaniqa Training Programme Module 5".

- ↑ "New lease of life for resurrection drug".

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 "Supply of sleeping sickness drugs confirmed".

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 "Sanofi-Aventis Access to Medicines Brochure".

- ↑ "IFPMA Health Initiatives: Sleeping Sickness".

- ↑ Azziz R. "The evaluation and management of hirsutism. Obstet Gynaecol 2003; 101: 995 -1007".

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Blume-Peytavi U, Gieler U, Hoffmann R, Shapiro J,. "Unwanted Facial Hair: Affects, Effects and Solutions. Dermatology. 2007; 215(2): 139-46".

- ↑ Barth JH, Catalan J, Cherry CA, Day A. "Psychological morbidity in women referred for treatment of hirsutism. J Psychosom Res. 1993 Sep; 37(6): 615-9".

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Jackson J, Caro JJ, Caro G, Garfield F, Huber F, Zhou W, Lin CS, Shander D, Schrode K, and the Eflornithine HCl Study Group. "The effect of eflornithine 13.9% cream on the bother and discomfort due to hirsutism. Int J Derm 2007; 46: 976-981".

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "NHS and UKMi New Medicines Profile".

- ↑ Balfour JA, McClellan K. "Topical Eflornithine. Am J Clin Dermatol 2001; 2(3): 197-201".

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Schrode K, Huber F, Staszak J, Altman DJ, and the Eflornithine Study Group. "Evaluation of the long-term safety of eflornithine 15% cream in the treatment of women with excessive facial hair. Presented at 58th Annual Meeting of the Academy of Dermatology 2000, 10–15 March, San Francisco; USA, Poster 294".

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Hamzavi I, Tan E, Shapiro S, Harvey l. "A randomized bilateral vehicle-controlled study of eflornithine cream combined with laser treatment versus laser treatment alone for facial hirsutism in women. J Am Acad Dermatol 2007; 57(1): 54-59".

- ↑ Hoffmann R. "A 4-month, open-label study evaluating the efficacy of eflornithine 11.5% cream in the treatment of unwanted facial hair in women using TrichoScan. Eur J Dermatol 2008; 18(1): 65-70".

- ↑ "Sanofi-Aventis 2005 Sustainable Development Report".

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Priotto, Gerardo, et al. "Safety and effectiveness of first line eflornithine for Trypanosoma brucei gambiense sleeping sickness in Sudan: cohort study." Bmj 336.7646 (2008): 705-708.

- ↑ Chappuis, François, et al. "Eflornithine is safer than melarsoprol for the treatment of second-stage Trypanosoma brucei gambiense human African trypanosomiasis." Clinical Infectious Diseases 41.5 (2005): 748-751.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 Vincent, Isabel M., et al. "A molecular mechanism for eflornithine resistance in African trypanosomes." PLoS pathogens 6.11 (2010): e1001204.

- ↑ Sayé, Melisa, et al. "Proline Modulates the Trypanosoma cruzi Resistance to Reactive Oxygen Species and Drugs through a Novel D, L-Proline Transporter." PloS one 9.3 (2014): e92028.

- ↑ Barrett, M. P., et al. "Human African trypanosomiasis: pharmacological re‐engagement with a neglected disease." British journal of pharmacology 152.8 (2007): 1155-1171.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 27.2 Paul, F. "Revival of 2-(difluoromethyl) ornithine (DFMO), an inhibitor of polyamine biosynthesis, as a cancer chemopreventive agent." Biochemical Society Transactions 35.Pt 2 (2007): 353-355.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 Gerner, Eugene W., and Frank L. Meyskens. "Polyamines and cancer: old molecules, new understanding." Nature Reviews Cancer 4.10 (2004): 781-792.

- ↑ "Alzheimer's breakthrough: Scientists may have found potential cause of the disease in the behaviour of immune cells - giving new hope to millions - Health News - Health & Families - The Independent". Retrieved April 14, 2015.

- ↑ Kan, M. J.; Lee, J. E.; Wilson, J. G.; Everhart, A. L.; Brown, C. M.; Hoofnagle, A. N.; Jansen, M.; Vitek, M. P.; Gunn, M. D.; Colton, C. A. (2015). "Arginine Deprivation and Immune Suppression in a Mouse Model of Alzheimer's Disease". Journal of Neuroscience 35 (15): 5969. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4668-14.2015.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 "Vaniqa US Patient Information Leaflet".

- ↑ "Ornidyl facts".

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 "Vaniqa Summary of Product Characteristics 2008".

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 "Ornidyl Drug Information".

- ↑ Malhotra B, Noveck R, Behr D, Palmisano M. "Percutaneous absorption and pharmacokinetics of Eflornithine HCI 13.9% cream in women with unwanted facial hair. J Clin Pharmacol 2001; 41: 972-978".

- ↑ "Vaniqa Product Monograph".

- ↑ Balfour JA, McClellan K. Topical Eflornithine. "Am J Clin Dermatol 2001; 2(3): 197-201".

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Metcalf, B. W.; Bey, P.; Danzin, C.; Jung, M. J.; Casara, P.; Vevert, J. P. (1978). "Catalytic irreversible inhibition of mammalian ornithine decarboxylase (E.C.4.1.1.17) by substrate and product analogs". Journal of the American Chemical Society 100 (8): 2551. doi:10.1021/ja00476a050.

- ↑ Ho, W.; Tutwiler, G. F.; Cottrell, S. C.; Morgans, D. J.; Tarhan, O.; Mohrbacher, R. J. (1986). "Alkylglycidic acids: Potential new hypoglycemic agents". Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 29 (11): 2184. doi:10.1021/jm00161a009.

External links

- WHO Eflornithine page

- Almirall

- Sanofi Aventis

- Vaniqa

- History of Drug Development for African Sleeping Sickness

- Chemoprevention

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||