Efficient cake-cutting

Efficient cake-cutting is a problem in economics and computer science. It involves a heterogenous resource, such as a cake with different toppings or a land with different coverings, that is assumed to be divisible - it is possible to cut arbitrarily small pieces of it without destroying their value. The resource has to be divided among several partners who have different preferences over different parts of the cake, i.e., some people prefer the chocolate toppings, some prefer the cherries, some just want as large a piece as possible, etc. The division should be economically efficient. Several definitions to efficiency are described below.

Most often, efficiency is studied in connection with fairness, and the goal is to find a division which satisfies both efficiency and fairness criteria.

Assumptions

There is a cake C, which is usually assumed to be either a finite 1-dimensional segment, a 2-dimensional polygon or a finite subset of the multidimensional Euclidean plane Rd.

There are n people. Each person i has a subjective value function Vi which maps subsets of C to numbers.

C has to be divided to n disjoint subsets, such that each person receives a disjoint subset. The piece allocated to person i is called Pi, and  .

.

Example cake

In the following lines we will use the following cake as an illustration.

- The cake has two parts: chocolate and vanilla.

- There are two people: Alice and George.

- Alice values the chocolate as 9 and the vanilla as 1.

- George values the chocolate as 6 and the vanilla as 4.

Efficiency criteria

Efficiency can be defined in several ways.

First, we say that a division Q Pareto-dominates a division P, if at least one person feels that Q is better than P, and no person feels that Q is worse than P. In symbols:

and

and

A Pareto efficient (PE) division is a division that is not Pareto-dominated by any other division, i.e., it cannot be improved without objection. In the example cake, many PE divisions are possible. For example, every division that gives the entire cake to a single person is PE, since every change in the division will raise the objection of that single person. Of course a PE division is not necessarily fair.

A division that is both Pareto-efficient and proportional will be called PEPR and a division that is both PE and envy-free will be called PEEF for short.

A utilitarian-maximum (UM) division is a division which maximizes the sum of the subjective values of the agents (the name comes from the utilitarian philosophy). Every UM division is PE, but the opposite is not true.

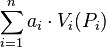

The concept of utilitarian-optimality can be generalized by assigning weights to the utilities of the agents. A Weighted-utilitarian-mamximum (WUM) division is a division maximizing a function of the following form:

Where the ai are positive constants. Every WUM division is PE. Moreover, every PE division is WUM for some selection of weights.[1]

The WUM concept can be further generalized to social welfare functions that are not necessarily linear. In general, a division is welfare-maximizing (WM) if it maximizes a certain welfare function that is monotonically increasing relative to the utility functions of the agents. Every WM division is PE, and every PE division is WM for some welfare function.

Finding efficient divisions

Disconnected pieces

When the value functions are additive, welfare-maximizing divisions always exist. Intuitively, we can give each fraction of the cake to the partner that values it the most, and the result is a UM division. In the example cake, a UM division would give the entire chocolate to Alice and the entire vanilla to George, achieveing a utilitarian value of 9+4=13.

This process is easy to carry out when the value functions are piecewise-constant, i.e. the cake can be divided to a finite number of pieces such that the value density of each piece is constant for all people.

What happens when the value functions are general (not piecewise-constant)?

The simple procedure of "give each piece to the one which wants it the most" does not work because there is an infinite number of different "pieces" to consider.

The good news is that UM divisions still exist. Theorem 2 of [2] proves the existence of UM divisions based on a generalization of the simple procedure, using the Radon-Nikodym derivatives of the value functions.

The bad news is that no finite algorithm can find a UM division. Proof:[3] A finite algorithm has value-data only about a finite number of pieces. I.e. there is only a finite number of subsets of the cake, for which the algorithm knows the valuations of the partners. Suppose the algorithm has stopped after having value-data about k subsets. Now, it may be the case that all partners answered all the queries as if they have the same value measure. In this case, the largest possible utilitarian value that the algorithm can achieve is 1. However, it is possible that deep inside one of the k pieces, there is a subset which two partners value differently. In this case, there exists a super-proportional division, in which each partner receives a value of more than 1/n, so the utilitarian value is strictly more than 1. Hence, the division returned by the finite algorithm is not UM.

Connected pieces

When the cake is 1-dimensional and the pieces must be connected, the simple algorithm of assigning each piece to the agent that values it the most no longer works, even when the pieces are piecewise-constant. In this case, the problem of finding a UM division is NP-hard, and furthermore no FPTAS is possible unless P=NP.

There is a 8-factor approximation algorithm, and a fixed-parameter tractable algorithm which is exponential in the number of players.[4]

For every set of positive weights, a WUM division exists and can be found in a similar way.

Combining efficiency and fairness

PEPR division - impossibility result

A PE division can be achieved trivially by giving the entire cake to a single partner. But, a PE division which is also proportional cannot be found by a finite algorithm. The proof[3] is essentially the same as for UM divisions.

PEEF division - general cakes

For n people with additive value functions, a PEEF division always exists.[5] The proof relies on the simple fact that, for every set of positive weights, a WUM division - a division maximizing the weighted utilitarian value - is PE. Here is an intuitive explanation:

- For every weight vector x=[x1,...,xn], find all WUM divisions - all divisions maximizing the function

. This maximization is done by giving each tiny piece of cake to the person i for whom

. This maximization is done by giving each tiny piece of cake to the person i for whom  is the largest. If there are two or more people for whom this value is the same, then every arbitrary division of that piece between them results in a WUM division.

is the largest. If there are two or more people for whom this value is the same, then every arbitrary division of that piece between them results in a WUM division. - A WUM division can be very unfair; for example, if xi is very small, then agent i might get the entire cake; if xi is very large, then agent i might get no cake at all. To mitigate this, consider, for every division, the vector of values enjoyed by the people, i.e. the vector: [V1(P1),...,Vn(P1)]. Make this the new set of weight vectors and return to step 1.

- By the Kakutani fixed-point theorem, this process has a fixed point, i.e., there is a vector x such that, one of the WUM divisions belonging to x generates a vector of values proportional to x. This division is obviously PE (because every WUM division is PE). It is also possible to show that this division is envy-free. Hence a PEEF division exists.

As an illustration, consider the example cake. Since there are two agents, the vector x can be represented by a single number - the ratio of the weight of Alice to the weight of George:

- If the ratio is less than 1:4, then a WUM division should give the entire cake to Alice. The ratio of values enjoyed by the people will be infinite (or 1:0), so of course no fixed point will be found in this range.

- If the ratio is exactly 1:4, then the entire chocolate should be given to Alice, but the vanilla can be divided arbitrarily between Alice and George. The ratio of values of the WUM divisions ranges between 1:0 and 9:4. This range does not contain the ratio 1:4, hence the fixed point is not here.

- If the ratio is between 1:4 and 9:6, then the entire vanilla should be given to George and the entire chocolate should be given to Alice. The ratio of values is 9:4, which is not in the range, so the fixed point is not found yet.

- If the ratio is exactly 9:6, then the entire vanilla should be given to George but the chocolate can be divided arbitrarily between Alice and George. The ratio of values of the WUM divisions ranges between 9:4 and 0:1. We see that 9:6 is in the range so we have a fixed point. It can be achieved by giving to George the entire vanilla and 1/6 of the chocolate (for a total value of 5) and giving to Alice the remaining 5/6 of the chocolate (for a total value of 7.5). This division is PEEF.

[6] provides an additional explanation of Weller's existence theorem from a geometric perspective.

[7] contains further discussion about PEEF division in the case of additive utilities.

PEEF division - special cakes

If the cake is a 1-dimensional interval and each person must receive a connected interval, the following general result holds: if the value functions are strictly monotonic (i.e. each person strictly prefers a piece over all its proper subsets) then every EF division is also PE.[7] Hence, the division produced by [8] is PEEF.

If the cake is a 1-dimensional circle (i.e. an interval whose two endpoints are topologically identified) and each person must receive a connected arc, then the previous result does not hold: an EF division is not necessarily PE. Additionally, there are pairs of (non-additive) value functions for which no PEEF division exists. However, if there are 2 agents and at least one of them has an additive value function, then a PEEF division exists.[9]

If the cake is 1-dimensional but each person may receive a disconnected subset of it, then an EF division is not necessarily PE. In this case, more complicated algorithms are required for finding a PEEF division.

If the value functions are additive and piecewise-constant, then there is an algorithm that finds a PEEF division.[10] If the value density functions are additive and Lipschitz continuous, then they can be approximated as piecewise-constant functions "as close as we like", therefore that algorithm approximates a PEEF division "as close as we like".[10]

Optimal EF division

An EF division is not necessarily UM.[11][12] One approach to handle this difficulty is to find, among all possible EF divisions, the EF division with the highest utilitarian value. This problem has been studied for a cake which is a 1-dimensional interval, each person may receive disconnected pieces, and the value functions are additive:[13]

- For n agents with piecewise-constant valuations: create a set of totally constant pieces. solve a set of linear equations. Give each agent a fraction of each totally constant piece.

- For 2 agents with piecewise-linear valuations: for each point in the cake, calculate the ratio between the utilities: r=u1/u2. Give player 1 the points with r>=r* and player 2 the points with r<r*, where r* is a threshold calculated so that the division is envy-free. In general r* cannot be calculated because it might be irrational, but in practice, when the valuations are piecewise-linear, r* can be approximated by an "irrational search" approximation algorithm.

- For n agents with general valuations: additive approximation to envy and efficiency, based on the piecewise-constant-valuations algorithm.

See also

References

- ↑ Varian, Hal R. (1976). "Two problems in the theory of fairness". Journal of Public Economics 5 (3-4): 249–260. doi:10.1016/0047-2727(76)90018-9.

- ↑ Dubins, Lester Eli; Spanier, Edwin Henry (1961). "How to Cut a Cake Fairly". The American Mathematical Monthly 68: 1. doi:10.2307/2311357. JSTOR 2311357.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Brams, Steven J.; Taylor, Alan D. Fair Division [From cake-cutting to dispute resolution]. p. 48. ISBN 0521556449.

- ↑ Aumann, Yonatan; Dombb, Yair; Hassidim, Avinatan (2013). Computing Socially-Efficient Cake Divisions. AAMAS.

- ↑ Weller, D. (1985). "Fair division of a measurable space". Journal of Mathematical Economics 14: 5. doi:10.1016/0304-4068(85)90023-0.

- ↑ Barbanel, J. (2010). "A Geometric Approach to Fair Division". The College Mathematics Journal 41 (4): 268. doi:10.4169/074683410x510263.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Berliant, M.; Thomson, W.; Dunz, K. (1992). "On the fair division of a heterogeneous commodity". Journal of Mathematical Economics 21 (3): 201. doi:10.1016/0304-4068(92)90001-n.

- ↑ Su, F. E. (1999). "Rental Harmony: Sperner's Lemma in Fair Division". The American Mathematical Monthly 106 (10): 930. doi:10.2307/2589747. JSTOR 2589747. Based on work by Forest Simmons (1980).

- ↑ Thomson, W. (2006). "Children Crying at Birthday Parties. Why?". Economic Theory 31 (3): 501. doi:10.1007/s00199-006-0109-3.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Reijnierse, J. H.; Potters, J. A. M. (1998). "On finding an envy-free Pareto-optimal division". Mathematical Programming 83: 291. doi:10.1007/bf02680564.

- ↑ Caragiannis, I.; Kaklamanis, C.; Kanellopoulos, P.; Kyropoulou, M. (2011). "The Efficiency of Fair Division". Theory of Computing Systems 50 (4): 589. doi:10.1007/s00224-011-9359-y.

- ↑ Aumann, Y.; Dombb, Y. (2010). "The Efficiency of Fair Division with Connected Pieces". Internet and Network Economics. Lecture Notes in Computer Science 6484. p. 26. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-17572-5_3. ISBN 978-3-642-17571-8.

- ↑ Cohler, Yuga Julian; Lai, John Kwang; Parkes, David C; Procaccia, Ariel (2011). Optimal Envy-Free Cake Cutting. AAAI.