Edward Steichen

| Edward Steichen | |

|---|---|

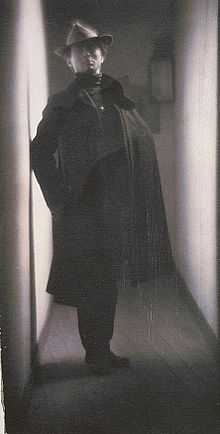

Edward Steichen, photographed by Fred Holland Day (1901) | |

| Born |

Éduard Jean Steichen March 27, 1879 Bivange, Luxembourg |

| Died |

March 25, 1973 (aged 93) West Redding, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Nationality | American |

| Known for | Painting, Photography |

Edward Jean Steichen (March 27, 1879 – March 25, 1973) was a Luxembourgian American photographer, painter, and art gallery and museum curator.

Steichen was the most frequently featured photographer in Alfred Stieglitz' groundbreaking magazine Camera Work during its run from 1903 to 1917. Together Stieglitz and Steichen opened the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, which eventually became known as 291 after its address.

His photos of gowns for the magazine Art et Décoration in 1911 are regarded as the first modern fashion photographs ever published. From 1923 to 1938, Steichen was a photographer for the Condé Nast magazines Vogue and Vanity Fair while also working for many advertising agencies including J. Walter Thompson. During these years, Steichen was regarded as the best known and highest paid photographer in the world. In 1944, he directed the war documentary The Fighting Lady, which won the 1945 Academy Award for Best Documentary.

After World War II, Steichen was Director of the Department of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art until 1962. While at MoMA, he curated and assembled the exhibit The Family of Man, which was seen by nine million people.

Early life

Steichen was born Éduard Jean Steichen in Bivange, Luxembourg, the son of Jean-Pierre and Marie Kemp Steichen.[1] Jean-Pierre Steichen initially immigrated to the United States in 1880.[1] Marie Steichen brought the infant Eduard along once Jean-Pierre had settled in Chicago, in 1881.[2] The family, with the addition of Eduard's younger sister Lilian, moved to Milwaukee in 1889, when Steichen was 10.[3]

In 1894, at the age of fifteen, Steichen began a four-year lithography apprenticeship with the American Fine Art Company of Milwaukee.[4] After hours, he would sketch and draw, and began to teach himself to paint.[5] Having come across a camera shop near to his work, he visited frequently with curiosity until he persuaded himself to buy his first camera, a secondhand Kodak box "detective" camera, in 1895.[6] Steichen and his friends who were also interested in drawing and photography pooled together their funds, rented a small room in a Milwaukee office building, and began calling themselves the Milwaukee Art Students League.[7] The group also hired Richard Lorenz and Robert Schade for occasional lectures.[4]

Steichen was naturalized as a U.S. citizen in 1900 and signed the naturalization papers as Edward J. Steichen; however, he continued to use his birth name of Eduard until after the First World War.[8]

Steichen married Clara Smith in 1903. They had two daughters, Katherine and Mary. In 1914, Clara accused her husband of having an affair with artist Marion H. Beckett, who was staying with them in France. The Steichens left France just ahead of invading German troops. In 1915, Clara Steichen returned to France with her daughter Kate, staying in their house in the Marne in spite of the war. Steichen returned to France with the Photography Division of the American Army Signal Corps in 1917, whereupon Clara returned to the United States. In 1919, Clara Steichen sued Marion Beckett for having an affair with her husband, but was unable to prove her claims.[9][10] Clara and Edouart Steichen eventually divorced in 1922. Steichen married Dana Desboro Glover in 1923. She died of leukemia in 1957. In 1960, aged 80, Steichen married Joanna Taub and remained married to her until his death, which occurred two days before his 94th birthday. Joanna Steichen died on July 24, 2010, in Montauk, New York, aged 77.[11]

Partnership with Stieglitz

Steichen met Alfred Stieglitz in 1900, while stopping in New York City en route to Paris from his home in Milwaukee.[12] In that first meeting, Stieglitz expressed praise for Steichen's background in painting and bought three of Steichen's photographic prints.[13]

In 1902, when Stieglitz was formulating what would become Camera Work, he asked Steichen to design the logo for the magazine with a custom typeface.[14] Steichen was the most frequently featured photographer in the journal.

In 1904, Steichen began experimenting with color photography. He was one of the first people in the United States to use the Autochrome Lumière process. In 1905, Stieglitz and Steichen created the Little Galleries of the Photo-Secession, which eventually became known as 291 after its address. It presented among the first American exhibitions of Henri Matisse, Auguste Rodin, Paul Cézanne, Pablo Picasso, and Constantin Brâncuși.

In 1911, Steichen was "dared" by Lucien Vogel, the publisher of Jardin des Modes and La Gazette du Bon Ton , to promote fashion as a fine art by the use of photography.[15] Steichen took photos of gowns designed by couturier Paul Poiret,[15] which were published in the April 1911 issue of the magazine Art et Décoration.[15] According to Jesse Alexander, this is "... now considered to be the first ever modern fashion photography shoot. That is, photographing the garments in such a way as to convey a sense of their physical quality as well as their formal appearance, as opposed to simply illustrating the object."[16]

Serving in the US Army in World War I (and the US Navy in the Second World War), Steichen commanded significant units contributing to military photography. After World War I, during which he commanded the photographic division of the American Expeditionary Forces, he reverted to straight photography, gradually moving into fashion photography. Steichen's 1928 photo of actress Greta Garbo is recognized as one of the definitive portraits of Garbo.

Later work

The initial publication of Ansel Adams' image Moonrise, Hernandez, New Mexico was in U.S. Camera Annual 1943, after being selected by Steichen, who was serving as photo judge for the publication.[17] This gave Moonrise an audience before its first formal exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1944.[18]

During World War II, Steichen served as Director of the Naval Aviation Photographic Unit.[19][20] His war documentary The Fighting Lady won the 1945 Academy Award for Best Documentary.

After the war, Steichen served as the Director of Photography at New York's Museum of Modern Art until 1962. Among other accomplishments, Steichen is appreciated for creating The Family of Man, a vast exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art consisting of over 500 photos that depicted life, love and death in 68 countries. Steichen's brother-in-law, Carl Sandburg, wrote a prologue for the exhibition catalog. As had been Steichen's wish, the exhibition was donated to the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. It is now permanently housed in the Luxembourg town of Clervaux.[21] In 1962, Steichen hired John Szarkowski to be his successor at the Museum of Modern Art.

On December 6, 1963, Steichen was presented with the Presidential Medal of Freedom by President Lyndon Johnson.

In 1970, an evening show was presented in Arles during The Rencontres d'Arles festival: "Edward Steichen, photographe" by Martin Boschet.

A show of early color photographs by Steichen was held at Mudam Luxembourg from July 14 to September 3, 2007.[22]

Steichen purchased a farm that he called Umpawaug in 1928, just outside West Redding, Connecticut.[23] Steichen lived there until his death in 1973.[24] After his death, Steichen's farm was made into a park, known as Topstone Park.[25] Topstone Park is open seasonally to this day.[26]

The Pond–Moonlight

In February 2006, a print of Steichen's early pictorialist photograph, The Pond—Moonlight (1904), sold for what was then the highest price ever paid for a photograph at auction, U.S. $2.9 million. (See List of most expensive photographs).

Steichen took the photograph in Mamaroneck, New York near the home of his friend, art critic Charles Caffin. The photo features a wooded area and pond, with moonlight appearing between the trees and reflecting on the pond. While the print appears to be a color photograph, the first true color photographic process, the autochrome process, was not available until 1907. Steichen created the impression of color by manually applying layers of light-sensitive gums to the paper. Only three known versions of the Pond—Moonlight are still in existence and, as a result of the hand-layering of the gums, each is unique. In addition to the auctioned print, the other two versions are held in museum collections. The extraordinary sale price of the print is, in part, attributable to its one-of-a-kind character and to its rarity.[27]

Gallery

-

"Landscape with Avenue of Trees," a painting by Steichen, 1902

-

Portrait of Auguste Rodin by Steichen, 1902

-

The cover of Camera Work, showing Steichen's design and custom typeface. Also, in this specific issue, Issue 2, the entire volume was devoted to Steichen's photographs.

-

"Self-portrait", by Edward Steichen. Published in Camera Work No 2, 1903

-

Portrait of J.P. Morgan, taken in 1903

-

The Flatiron Building in a photograph of 1904, taken by Steichen.

-

"Experiment in Three-Color Photography," by Steichen, published in Camera Work No 15, 1906

-

"Pastoral – Moonlight," by Steichen, published in Camera Work No 20, 1907

-

"Eugene, Stieglitz, Kühn and Steichen Admiring the Work of Eugene," by Frank Eugene from 1907. From left to right are Eugene, Alfred Stieglitz, Heinrich Kühn, and Steichen.

-

Picture by Steichen of Brâncuși's studio, 1920

-

Portrait of Constantin Brâncuși, taken at Steichen's home & studio at Voulangis, in 1922.

-

"Wind Fire." Thérèse Duncan, the adopted daughter of Isadora Duncan, dancing at the Acropolis of Athens, 1921, by Steichen.

-

"Aircraft of Carrier Air Group 16 return to the USS Lexington (CV-16) during the Gilberts operation, November 1943." Photographed by Commander Edward Steichen, USNR.

-

CDR Edward Steichen photographed above the deck of the aircraft carrier USS Lexington (CV-16) by Ens Victor Jorgensen, November 1943.

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 4

- ↑ Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 6

- ↑ Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 16

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Gedrim, Ronald J. (1996). Edward Steichen: Selected Texts and Bibliography Oxford, UK: Clio Press. ISBN 1-85109-208-0, p. xiii

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 28

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 29

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 42

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 66

- ↑ "ARTIST'S WIFE SUES FOR LOSS OF HIS LOVE; Mrs. Edouard Steichen Says Marion Beckett Alienated Her Husband's Affections. ASKS FOR $200,000 DAMAGES Declares Other Woman Followed the Painter to Paris, Where He Was Honored by France". The New York Times. July 5, 1919. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ Mitchell, Emily (2007). The last summer of the world. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-06487-2. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- ↑ "Joanna Steichen obituary". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4, p. 74

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 75

- ↑ Roberts, Pam (1997) "Alfred Stieglitz, 291 Gallery and Camera Work," contained in Stieglitz, Alfred (1997) Camera Work: The Complete Illustrations 1903–1917 Köln: Taschen. ISBN 3-8228-8072-8, p. 17

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Niven (1997), p. 352

- ↑ Alexander, Jesse, "Edward Steichen: Lives in Photography," HotShoe magazine, no. 151, December/January 2008, pp. 66 – 67

- ↑ Alinder, Mary Street (1996). Ansel Adams: a Biography. New York: Henry Holt and Co. ISBN 0-8050-5835-4, p. 192

- ↑ Alinder (1996), p. 193

- ↑ Faram, Mark D. (2009), Faces of War: The Untold Story of Edward Steichen's WWII Photographers, Berkeley Caliber, New York, New York, ISBN 978-0-425-22140-2

- ↑ Budiansky, Stephen, "The Photographer who Took the Navy's Portrait", World War II, Volume 26, No. 2, July/August 2011, p. 25

- ↑ Serge Moes. "Luxembourg Tourist Office in London – Clervaux". Luxembourg.co.uk. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ "Musée d'Art Moderne Grand-Duc Jean, Luxembourg, v3.0". Mudam.lu. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 530

- ↑ Niven (1997), p. 698

- ↑ Prevost, Lisa, the New York Times, "An Upscale Town With Upcountry Style," 3 January 1999

- ↑ Town of Redding (2012-05-31). "Town of Redding - Topstone Park". Townofreddingct.org. Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ "World | Americas | Rare photo sets $2.9m sale record". BBC News. February 15, 2006. Retrieved April 28, 2010.

References

- Haskell, Barbara (2000). Edward Steichen. New York: Whitney Museum of American Art.

- DePietro, Anne Cohen; Goley, Mary Anne (2003). Eduard Steichen: Four Paintings in Context. Hollis Taggart Galleries.

- DePietro, Anne Cohen (1985). The Paintings of Eduard Steichen. Huntington, NY: The Heckscher Museum. LCCN 85-80519 (Exhibition Catalog).

- Mitchell, Emily (2007). The Last Summer of the World. Norton. (A fictional narrative about Steichen.)

- Niven, Penelope (1997). Steichen: A Biography. New York: Clarkson Potter. ISBN 0-517-59373-4.

- Sandeen, Eric J. (1995). Picturing an Exhibition: The Family of Man and 1950's America. University of New Mexico Press.

- Smith, Joel (1999). Edward Steichen: The Early Years. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Steichen, Edward (1955). The Family of Man: The Greatest Photographic Exhibition of All Time. New York: Maco Pub. Co for the Museum of Modern Art.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Edward Steichen |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Edward Steichen. |

- Edward J. Steichen Online

- Edward Steichen Photographs

- bloom! Experiments in color photography by Edward Steichen at Mudam

- Edward Steichen at Museo Reina Sofia in Madrid, Spain from June 25, 2008, to September 22, 2008

- -- David Joseph (DJ) Marcou's cover-story Edward Steichen, HonFRPS: Renaissance Man in March 2004 RPS Journal, pp. 72-75.

- Triond link to David J. Marcou's article "From Luxembourg and America to the World: Edward Steichen's Photographic Legacy" relating to Mr. Steichen's Wisconsin background, in particular, can be found on La Crosse History Unbound Website.

- "A list of the 1963 recipients of the Medal of Freedom", John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

- Edward Steichen Archive at The Museum of Modern Art

|