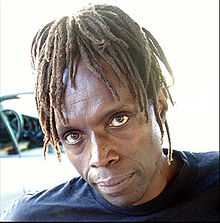

Edward C. Lawson

Edward C. Lawson was an African American civil rights activist, who was the plaintiff in the case of Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352 (1983), in which the United States Supreme Court ruled that a California statute authorizing a police officer to arrest a person for refusing to present identification was unconstitutionally vague.

Civil rights case

Between March 1975 and January 1977, Lawson was detained approximately fifteen times, as a pedestrian or as a diner in a cafe, and asked to present identification; some detentions lasted minutes, others lasted hours. He was arrested several times pursuant to California Penal Code § 647(e),[1] but prosecuted only twice, with one conviction (the second charge was dismissed). In 1975, Lawson, representing himself (known as pro se), brought a civil rights action against San Diego police chief William Kolender and others, taking the case through U.S. District Court and ultimately to the U.S. Supreme Court, which ruled in his favor.

The U.S. District Court ruled in Lawson's favor, enjoining enforcement of the law. Kolender appealed the ruling the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit; the ruling in Lawson v. Kolender, 658 F.2d 1362 (9th Cir. 1981) upheld the District Court, voiding § 647(e).[2] Kolender appealed the ruling to the U.S. Supreme Court, which in 1983 upheld the Court of Appeals in voiding the law.[3][4] This case is of historical importance not only because the California statute was voided, but also because it is one of the few examples of an ordinary citizen successfully representing himself all the way through the U.S. Supreme Court. Lawson received political support at the time from prominent Black leaders including Jesse Jackson, activist/comedian Dick Gregory, U.S. Congresswoman Maxine Waters D-Los Angeles, U.S. Congressman John Conyers D-Detroit, and others.

Lawson's Supreme Court brief was accompanied by amici curiae briefs from the ACLU, the National Lawyers Guild, the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, and others.

In 1983, Carl Stern, the CBS Evening News U.S. Supreme Court reporter commented that this case was the most reported U.S. Supreme Court case that year. Stern was referring to front page newspaper articles in the New York Times, The Washington Post, The Chicago Tribune, The Miami Herald, The Los Angeles Times as well as articles in Newsweek Magazine, Time Magazine, Fortune Magazine, The Village Voice and other news publications. And additionally Lawson made repeated appearances on The Oprah Winfrey Show, The Phil Donahue Show, Larry King Live, Crossfire (TV series), The Ricki Lake Show, The Today Show, and Good Morning America.

Harvard University law professor Lawrence Tribe commented during an appearance on The Oprah Winfrey Show television program that this case was the last time that the U.S. Supreme Court had decided favorably to a defendant in a civil rights case of this magnitude.

California Penal Code § 647(e) was repealed by the California Legislature in 2008.

1921 Tulsa race riot

By way of his grandmother, Lundy Bohanan, Edward C. Lawson is a direct descendant of a survivor of the 1921 Tulsa Race Riot and massacre in Oklahoma.

Death

On May 12, 2011, Edward C. Lawson died; This is reported by John Longenecker of Pro Per Inc., a longtime business partner and friend. To date, there has been no obituary. A report from a man with a similar name as Edward's relates that he died of pancreatic cancer.

- Edward C. Lawson -

Inveterate Pedestrian

Danced more than walked

Impassioned Voice

Cared more than talked

http://vimeo.com/groups/edwardlawson/videos/975968

See also

- Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada

- Kolender v. Lawson

- Police misconduct

- Racial profiling

- Stop and identify statutes

- Contempt of cop

- Driving While Black

- Arrest of Henry Louis Gates

External links

- Edward C. Lawson—official website

- U.S. Supreme Court video story

- Kolender v. Lawson, 461 U.S. 352 (1983)

- Jon Shane, author

- 1921 Tulsa Race Riot -- CNN

- 1921 Tulsa Race Riot -- OSU Library

- 2009-2011 Newark NJ

Notes

- ↑ California Penal Code §647(e) combined elements of a “stop and identify” law with elements of traditional vagrancy laws; it read, in relevant part,

- “Every person who commits any of the following acts is guilty of disorderly conduct, a misdemeanor: . . . (e) who loiters or wanders upon the streets or from place to place without apparent reason or business and who refuses to identify himself and to account for his presence when requested by any peace officer so to do, if the surrounding circumstances are such as to indicate to a reasonable man that the public safety demands such identification.”

- ↑ The Ninth Circuit held that § 647(e) violated the Fourth Amendment because it allowed arrest without probable cause, that it was void for vagueness, and that it invited arbitrary enforcement.

- ↑ A ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court is binding on all courts of inferior jurisdiction throughout the United States. But in voiding § 647(e) for vagueness, both the Ninth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court relied on a construction given that law by a California appellate court in People v. Solomon (1973), 33 Cal.App.3d 429. Consequently, the Supreme Court ruling did not necessarily invalidate nominally identical laws in other states.

- ↑ Because the U.S. Supreme Court were able to resolve Kolender on the issue of vagueness, they declined to rule on the Fourth Amendment issue. In Hiibel v. Sixth Judicial District Court of Nevada, 542 U.S. 177 (2004), the U.S. Supreme Court held that a Nevada law requiring persons detained upon reasonable suspicion of involvement in a crime to identify themselves to a peace officer did not violate the Fourth Amendment’s prohibition of unreasonable searches and seizures. The Court also held that, because Hiibel had no reasonable belief that his name would be used to incriminate him, the identification requirement did not violate the Fifth Amendment privilege against self-incrimination; however, the Court left open the possibility that Fifth Amendment privilege might apply in situations where there was a reasonable belief that giving a name could be incriminating (542 U.S. at 191).