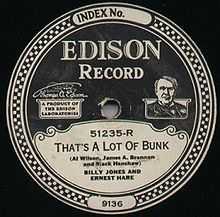

Edison Disc Record

The Edison Diamond Disc Record is a type of phonograph record marketed by Thomas A. Edison, Inc. on their Edison Record label from 1912 to 1929. They were named Diamond Discs because the matching Edison Disc Phonograph was fitted with a precision-made semi-permanent diamond stylus for playing them. Diamond Discs were incompatible with ordinary disc record players, the disposable steel needles of which would damage them while extracting hardly any sound. Uniquely, they are about 1/4 inch (6 mm) thick.

Edison had previously made only phonograph cylinders but decided to add a disc format to the product line because of the increasingly dominant market share of the shellac disc records (later called "78s" because of their typical rotational speed) made by competitors such as the Victor Talking Machine Company. Victor and most other makers recorded and played sound by a lateral or side-to-side motion of the stylus in the record groove, while in the Edison system the motion was vertical or up-and-down, known as "hill-and-dale" recording, as used for cylinder records. An Edison Disc Phonograph is distinguished by the diaphragm of the reproducer being parallel to the surface of the record. The diaphragm of a reproducer used for playing ordinary records is at a right angle to the surface.

In 1929 Edison also produced a short-lived series of ordinary thin lateral-cut "needle type" disc records.

History

|

Samuel Siegel and Marie Caveny play Ragtime Echoes

A 1918 Diamond Disc Record with Samuel Siegel on mandolin and Marie Caveny on ukulele. |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The grooves on an Edison Disc are smooth on the sides and have a variable depth. Standard lateral discs will have a more constant depth, but the sides of the groove are scalloped. As the Edison groove pitch (or "TPI", i.e. "threads per inch") was 150, a much finer grooving than that on lateral discs, Edison's 10-inch discs played considerably longer than Victor's or Columbia's -- up to nearly five minutes per side. The Edison Disc is also ¼-inch thick (supposedly to prevent warping), and was filled with wood flour, and later, china clay.[1]

Victor's system could not play Edison Discs as the needles used would cut through the recorded sound, and the Edison system could not play Victor or other lateral discs unless one used special equipment, like the Kent adapter. There is an example of a device to play Edison discs on a Victor machine.[2] The Brunswick Ultona and the Sonora Phonograph were the only machines besides the Diamond Disc player that could play Diamond Discs, but Edison made an attempt at curbing this (a phonograph/gramophone that could play Edison, Victor/lateral 78s, and Pathé discs) by stating "This Re-Creation should not be played on any instrument except the Edison Diamond Disc Phonograph and with the Edison Diamond Disc Reproducer, and we decline responsibility for any damage that may occur to it if this warning is ignored."[3]

Rise and fall

Edison discs enjoyed their greatest commercial success from the mid-1910s to the early 1920s, with sales peaking in 1920.[4] Diamond Discs arguably had better audio fidelity, but were more expensive than and incompatible with other brands of records, ultimately failing in the marketplace. Not least among the factors contributing to their downfall was Thomas Edison's insistence on imposing his own musical tastes on the catalog. As an elderly man who favored old-fashioned "heart" songs and had various idiosyncratic preferences about performance practices, he was increasingly out of touch with most of the record-buying public as the "Jazz Age" 1920s got underway. It was not until mid-decade that he reluctantly ceded control to a younger generation.

In 1926, an attempt at reviving interest in Edison records was made by introducing a long-playing Diamond Disc which still rotated at 80 rpm but tripled the standard groove pitch to 450 threads per inch by using an ultra-fine groove, achieving a playing time of 24 minutes per 10-inch disc (12 on each side) and 40 minutes per 12-inch disc. A special reproducer and modified feed screw mechanism were required to play them. There were problems with skipping, groove wall breakdown and overall low volume (about 40% of that of the regular Diamond Discs). Only 14 different "Edison Long Play" discs were issued before they were discontinued.

In August 1927, electronic recording began, making Edison the last major record company to adopt it, over two years after Victor, Columbia and Brunswick had converted from acoustical recording. Sales continued to drop, however, and although Edison Diamond Discs were available from dealers until the company left the record business in late October 1929, the last vertically-cut direct masters were recorded in the early summer of that year. Priority had been redirected to introducing a new line of Edison lateral or so-called "Needle Type" thin shellac records, compatible with ordinary record players, but although their audio quality was excellent this concession to commercial reality came too late to prevent the demise of Edison Records just one day before the 1929 stock market crash.

See also

- Edison Records

- Brunswick Records

- Victor Records

- Columbia Records

- Gramophone record

- Unusual types of gramophone records

References

- ↑ "Tim Gracyk's Phonographs, Singers, and Old Records -- Edison Diamond Discs: 1912 - 1929". Gracyk.com. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Very rare reproducer made for Victrola machines to play Edison DD records.". Pat.kagi.us. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "Tim Gracyk's Phonographs, Singers, and Old Records -- Brunswick Phonographs and Records". Gracyk.com. Retrieved 18 September 2014.

- ↑ "EDISON DIAMOND DISC MANUFACTURING PROCESSES - By Paul B. Kasakove / THOMAS A. EDISON, INC.". Mainspringpress.com. Retrieved 18 September 2014.