Eddy Merckx

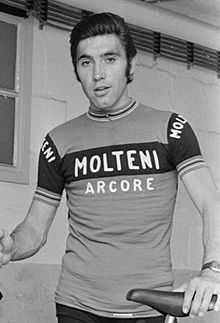

Merckx in 1973 | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal information | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Full name | Edouard Louis Joseph Merckx | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Nickname | The Cannibal | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Born |

17 June 1945 Meensel-Kiezegem, Brabant, Belgium[1] | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Height | 1.85 m (6 ft 1 in) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Weight | 74 kg (163 lb; 11.7 st) | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Team information | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| Current team | Retired | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Discipline | Road and track | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Role | Rider | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Rider type | All-rounder | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Amateur team(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1961–1964 | Evere Kerkhoek Sportif | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Professional team(s) | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1965 | Solo-Superia | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1966–1967 | Peugeot-BP-Michelin | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1968–1970 | Faema | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1971–1976 | Molteni | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1977 | Fiat | |||||||||||||||||||||

| 1978 | C&A | |||||||||||||||||||||

| Major wins | ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Medal record

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

Edouard Louis Joseph, Baron Merckx (Dutch pronunciation: [ˈmɛrks]) (born 17 June 1945), better known as Eddy Merckx, is a Belgian former professional road and track bicycle racer, considered to be the greatest cyclist ever. Merckx was caught doping three times.[2]

The French magazine Vélo described Merckx as "the most accomplished rider that cycling has ever known,"[3] while VeloNews of the United States declared him to be the greatest and most successful cyclist of all time.[4]

He dominated men's cycling in his era. Merckx, who turned professional in 1965, won the World Championship thrice, the Tour de France and Giro d'Italia five times each, and the Vuelta a España once. He also won all of professional cycling's classic "monument" races at least twice each (with 19 Classics victories in all).[3] Merckx was World Champion once as an amateur and three times as a professional, and he broke the world hour record before retiring in 1978.

Since then, Merckx has remained active in professional cycling through various commercial and sporting projects, most notably by manufacturing and selling his own line of bicycles, Eddy Merckx Cycles.[5]

Early life and amateur career

Eddy Merckx is one of three children born to a couple who ran a grocery in the middle-class area of Sint-Pieters-Woluwe, near Brussels, Belgium.[6] His brother and sister are twins.[7] The family moved to the suburb when he was young.[7]

He acquired his first racing bike, second-hand, when he was eight. His hero was Stan Ockers, who died in a fall on an Antwerp track in 1956.[7]

Merckx rode his first race at Laeken[2] on 16 July 1961,[8] riding for the Evere Kerkhoek Sportif club.[9] He rode 12 races before winning his first, at Petit-Enghien, on 1 October 1961.[3] Merckx moved from the youth to the senior amateur class two months early.[10] Patrick Sercu rode with him in newcomers' and junior races on the track at the Palais des Sports in Brussels. Merckx could not beat him on the track but Sercu said that when he saw Merckx on the road he believed he was looking at a future winner of the Tour de France.[10]

Professional career

Early years

In 1964 he rode the road race at the 1964 Summer Olympics and finished 12th.[11][n 1] In the same year, he became world amateur champion at Sallanches, France. He said his victory was tainted by the long list of riders who had won the amateur championship and done nothing afterwards.[10]

He turned professional on 29 April 1965,[1] after 80 wins as an amateur.[8] He joined Solo-Superia under Rik van Looy. One of the other riders was Jean van Buggenhout, who became his manager.[3] His first win was at Vilvoorde on 11 May. He came second to Walter Godefroot in the national championship and was picked for the national team for the world championship near San Sebastian, Spain. The race was won by Tom Simpson. Simpson rode normally for Peugeot and Merckx moved there the following year after nine wins with Solo.[1] There he won the first of seven editions of Milan – San Remo[12] still aged 20.

In 1967 he repeated his 1966 Milan – San Remo success and also won La Flèche Wallonne. His first grand tour was the 1967 Giro d'Italia, in which he won two stages and finished ninth. Later that year he out-sprinted Jan Janssen and the Spaniard Ramon Saez to become world professional champion at Heerlen, Netherlands.[12][13] Merckx was earning 125,000 Belgian francs a year when he won the championship (approx €25,000 at 2012 values). He didn't buy his first car until he had been a professional for three years.[10]

Move to Italy

At Peugeot, Merckx had to pay for his wheels and tyres.[10] In 1968 he moved to the Italian Faema team.[1][14] The Italian coffee machine company had returned to sponsorship, having backed teams led by van Looy and others in the past.[14] Coca-Cola offered Merckx a million Belgian francs (US$20,000 not adjusted for inflation) to ride in 1968, van Buggenhout urged him to accept, but Merckx refused believing himself not strong enough to ride both the Giro – which was important to Faema – and the Tour – which wasn't.[15][n 2]

Merckx won Paris–Roubaix and started his domination of the grands tours by becoming the first Belgian to win the Giro d'Italia in 1968.[16] He did this another four times, equalling the record of five by Alfredo Binda and Fausto Coppi.

In 1969, he first won Paris–Nice. In the time trial, he overtook the five-time Tour de France winner, Jacques Anquetil,[17] who for 15 years had been the world's best time-triallist. Merckx won Milan–San Remo, the Tour of Flanders and Liège–Bastogne–Liège.

During the 1969 Giro d'Italia, he was found to have used drugs and was disqualified.[8] (See below – Doping)

Tour de France

1969 Tour de France

The 1969 Tour de France was the first which Merckx won,[12] even though he was almost deprived of it by a doctor in Lille who found abnormalities in his heart rhythm.[18] Merckx was cleared to start after medical colleagues said the hearts of endurance athletes were often unusual.

Merckx won the 17th stage, over four cols from Luchon to Mourenx[n 3] by eight minutes after riding alone for 140 km.[12] He climbed the col du Tourmalet in a small group including Roger Pingeon and Raymond Poulidor, having dropped Felice Gimondi. On the final bend to the summit, Merckx attacked and opened a few seconds. By the foot of the col d'Aubisque he had more than a minute and by the top eight minutes. He maintained the pace for the remaining 70 km to Mourenx, an industrial town near Pau.

He won the general classification (yellow jersey), points classification (green jersey) and the mountains classification. No other rider has achieved this triple in the Tour de France, and only Tony Rominger and Laurent Jalabert have matched it in any grand tour.[n 4] Merckx also won the combination classification and the combativity award. Merckx led the race from stage six to twenty-two. His 17-minute 54 second margin of victory over second-placed Roger Pingeon has never been matched since. It was the first time a Belgian had won the Tour since Sylvère Maes 30 years earlier, and Merckx became a national hero.

1970 Tour de France

In the 1970 Tour de France, Merckx took the yellow jersey in the prologue, thrashing his bike. As the previous year he let the yellow jersey pass to a teammate, this time Italo Zilioli, taking it back after seven stages at Valenciennes. He won the prologue, in road stages, the final time trial and on Mont Ventoux. There he pushed himself so hard that he collapsed while talking to journalists, saying "No, it's impossible!"[19] He was carried to an ambulance for oxygen.[12] His eight stages equalled the record set in 1930 by Charles Pélissier.[20] He won the mountains classification and finished second in the sprinter's classification. He won by 12m 41s over Joop Zoetemelk.

1971 Tour de France

Merckx chose a different preparation for his third Tour de France in 1971. In order to arrive fresher and as well to be in better condition in the autumn, Merckx chose not to defend his title at the Tour of Italy and instead rode two-week-long stage races, the Critérium du Dauphiné Libéré and the Grand Prix du Midi Libre, both of which he won the first stage and held on to the lead of both races until the end. Merckx arrived at the start of the Tour which began that year in Mulhouse to the pre-Tour hype which was summed up by former winner Jacques Anquetil who, speaking on French television program Les Dossiers de l'Ecran the day before the race began, said he wished that Merckx would be defeated.[21] The only rider of the period to shake Merckx was the Spaniard, Luis Ocaña, who lived near Mont-de-Marsan in south-west France. Ocaña cared little for Merckx's reputation and attacked him on the Puy de Dôme, dropping him but not taking the yellow jersey. Three days later, Ocaña attacked when the race reached the Alps. By Orcières-Merlette he had taken 8m 41s out of the Belgian. By then resentment had built at the way Merckx was winning everything.[22] Chany wrote, "There was a feeling that it would be good for cycling if he lost."[23]The title on the front page of Paris-Match was: "Is Merckx going to kill the Tour?" A rider at the Grand Prix du Midi Libre was quoted as saying: "When you know how much Merckx is earning, you sometimes lose the will to make an effort if you're paid in loose change [rabais]."[23] The resentment left Merckx to chase Ocaña without help. One rider, Celestino Vercelli, said:

Merckx never let anybody break away. But that day... we don't know.... The start was on an upgrade and he wasn't that brilliant in the beginning. Maybe he was still warming up and his adversaries, Luis Ocaña, Joaquim Agostinho, Joop Zoetemelk, noticed that and decided to break away immediately. It cost him dearly because the stage was long and very hard and there were four or five climbs. He took it badly, because it had never happened to him to be behind and lose so much time. Usually he was the one who was nine minutes in front the others![24]

A rest day followed and then a stage from Orcières-Merlette to Marseille. It started with 20 km downhill, followed by 280 km along a valley. Merckx and his team attacked from the start, led by Rini Wagtmans, immediately gaining several minutes. But the speed downhill and the heavier braking needed for bends led rims to overheat, melting the glue that held tyres to the rim. It happened to several riders and Merckx lost some of his teammates as a result.[24]

Merckx got to Marseille half an hour faster than the fastest expected time. The entire Kas team finished outside the time limit but were reinstated.[25] Only 1,000 spectators were at the finish early enough. Among those too late was the mayor of the city, Gaston Deferre,[n 5] who decided to see the finish at the last moment but arrived after the riders had left for the showers and the officials for their hotels. He forbade the Tour to return to the city for the rest of his career.[22] It next stopped in Marseille in 1989, three years after his death. Despite a stage that averaged 45.4 km/h, Merckx cut Ocaña's lead only to 7m 32s. He waited for the Pyrenees. There, on the col de Mente, hail and rain flooded the road. Unable to shake off Ocaña on the way up, Merckx tried to do so on the way down. The storm broke at the summit. Merckx missed a bend, hit a low wall and fell. He got up straight away but two spectators had gone to help him. Ocaña ran into them, crashed heavily and was hit by Zoetemelk and then two other riders who had been following by a few seconds. Merckx who was descending the mountain fell a further two times before hearing what had happened behind him.[21] Ocaña's fall had taken him out of the race and gave the yellow jersey to Merckx, although he declined to wear it next morning in respect for the Spaniard.[22][26] Merckx won the Tour by 9m 51s over Zoetemelk and 11m 6s over Lucien Van Impe. After the Tour, the Belgian Cycling Federation named the team for the world championships and despite his wish to have several trade teammates on the team, Merckx would only have one trade teammate. In response, Merckx re-arranged his post-Tour schedule and trained with complete resolution to win. On a challenging circuit in Mendrisio, Switzerland Merckx attacked several times and broke away with Felice Gimondi whom he beat in the sprint to take his second rainbow jersey.[21]

1972 Tour de France

In 1972, there was anticipation of a rematch between Merckx and Ocaña.[27] Merckx won the prologue at Angers but lost the yellow jersey when Cyrille Guimard won the following day at St-Brieuc. Guimard held the lead for seven stages, despite growing knee pain. Merckx won the stage at Luchon on day eight and with it the lead. He kept the yellow jersey to the end, winning the sprint competition and coming second to Van Impe in the mountains. The battle with Ocaña fizzled out when the Spaniard crashed in the Pyrenees again,[27] falling on the Aubisque, and dropping out with a lung infection on the 15th day.[28]

With four wins, Merckx was approaching Jacques Anquetil's record of five, and the French public was becoming hostile. He had already been whistled at the finish in Vincennes after winning in 1970.[29] For that reason, the Tour organisers asked Merckx not to start in 1973; instead he won the Vuelta a España, where he beat Luis Ocaña and Bernard Thévenet, and he won the Giro.

1974 Tour de France

By 1974, "the wear and tear was beginning to show," Merckx acknowledged.[30] Yet he still won the Giro, the Tour de Suisse and the Tour de France, including its closing stage in Paris, within eight weeks. Far from challenging Merckx, Ocaña rode the Vuelta with bronchitis, started the Midi-Libre but dropped out, then broke a bone in the Tour de l'Aude. His sponsor, the pen and lighter company, Bic, fired him.[31][n 6]

The novelty of the Tour was its first excursion to England, for a criterium up and down an unopened bypass near Plymouth. By the ninth stage, the race looked over. Patrick Sercu had the sprinters' jersey after winning three stages, and Merckx was in yellow. The Dutchman, Gerben Karstens, challenged both by collecting repeated bonuses in the intermediate sprints each day but lost his chance in a war of words as well as wheels[32] when Sercu and Merckx joined forces as rivals against a common enemy. The race then settled in to ride round France in a heatwave. And then, said Chany, came a remarkable attack on the Mont du Chat, above Lac du Bourget.

Poulidor's tentative attack didn't succeed and next day he lost five minutes. But he twice more bettered Merckx in the Pyrenees, at St-Lary and on the Tourmalet. Merckx won the Tour 8m 4s ahead of Poulidor and a further three in front of Vicente Lopez-Carril. It left journalists divided about whether they had seen a remarkable comeback by Poulidor or the first signs of vulnerability in Merckx.[33] Michel Pollentier, "at the price of unbelievable contortions [on his bike]",[31] beat Merckx by 10 seconds in the time trial at Orléans just before Paris.

Victory gave Merckx five wins in the Tour, equalling Anquetil. Over the next 25 years, only Bernard Hinault and Miguel Indurain were able to equal him.

1975 Tour de France

Merckx's domination in the grands tours ended in 1975. The race started well – he held the yellow jersey for eight days, raising his total to 96 – but ended in disappointment.

The finishing climb on the Puy de Dôme (12 km, 7% gradient) was the beginning of the end for Merckx. The legendary giant of the Massif Central has provided the Tour with great drama over the years. This year's battle would write another chapter in Tour history. Just over 4 kilometers up the finishing climb, Thevenet charged off the front with Van Impe in tow. The two slowly pulled away from Merckx and Zoetemelk. The race leader, trying to limit his time loss, was forced to do all the work in pursuit of the breakaway. As Merckx tried to close the gap near the top of the climb he was punched by a spectator. Review of French TV film shows the man standing alongside the road with his hands at his side. As Merckx passes him the man punches him in the lower right abdomen (not a kidney punch as has been claimed in the past) with as much force as he probably could from launching the punch from a hip position. Most of the force was pushed away as the man's arm was thrown back from the momentum of the movement of Merckx up the hill. Merckx grabbed his side for a second. But, a second later, he had both hands back on the handlebar and was moving at the same speed as he was before the spectator hit him. The image of the spectator is very clear in the film. He was identified and charged with assault on Merckx that day and fined with symbolic one franc. The exhausted Merckx couldn't close the gap. But, he did hold on to finish third, 34 seconds behind Thevenet who was second and, Van Impe who was first. But, the Frenchman had landed a fatal blow that cut into the overall lead and trailed Merckx by only 58 seconds as the Tour headed into the Alps .

After a rest day in Nice, the Tour continued with a 5-climb stage. On the Col des Champs, the third climb of the day, Thevenet repeatedly attacked in an effort to crack the race leader. Gamely Merckx was able to cover all of Thevenet's moves and launched an attack of his own on the descent. Thevenet managed to catch Merckx in the valley just before the Col d'Allos. The always-aggressive Merckx, searching for weakness, attacked again on the Allos. Over the top with a lead, he plunged down the descent. On the narrow bumpy road, Merckx took all the risks necessary to gain time. He sailed through the bottom of the descent with over a minute lead on the Thevenet led chasers. The Cannibal then set his sights on the final climb to the top of Pra Loup. He had a 2-minute lead on the chasers as the road turned upward.

Merckx was 6 km from putting the race out of reach. However, the long breakaway effort had taken its toll and Merckx began to slow. Gimondi was the first to catch the leader, then Thevenet, then Van Impe and Zoetemelk. The Frenchman sensed a weakness and sprinted by the tired race leader. Thevenet took the stage win by 1m 58s over Merckx and gained the race lead.

Inspired by the yellow jersey, Thevenet attacked on the next stage and rode away from the Merckx group on the classic climb of the Col d'Izoard. He rode alone to win his second stage in a row. Thevenet's win and time gain widened the gap to the now second-place Merckx to 3m 20s. There was still one climbing stage remaining in the Alps and Merckx needed time gains.

Eddy Merckx had one intention at the start of stage 17 in Valloire, get back the yellow jersey. Merckx launched an all-out attack from the starting line, 225 km from the finish at the top of the Col d'Avoriaz. Misfortune struck early when Merckx slid and crashed heavily. Although injured, he quickly remounted his bicycle and continued the race. His injuries include a bruised hip and knee, as well as a broken jaw, but he continued to ride hard. Although struggling to breathe, he refused treatment. By the end of the stage, the injured Cannibal finished third, 2 seconds ahead of Thevenet. The "never say die" Belgian was fighting all adversities to the end.

Gamely, Merckx gained another 15 seconds on the final ITT in Chatel, but the finish in Paris was only four flat stages away. When the Tour reached the final stage, Thevenet had an insurmountable 2m 47s lead on Merckx and cruised down the Champs Elysees for his first Tour de France victory. Gracious in defeat the second-place Merckx said, "I tried everything and it didn't work. It's always the strongest that wins, and the strongest is Thevenet." The winner returned the compliment saying, "Tell me who was second to you and I will tell you the value of your victory."

He said riding the 1975 Tour did not in itself shorten his career, but...

...the fact that I continued in the 1975 Tour de France after I crashed definitely did shorten it. My build-up to that race had already been problematical, and actually I wasn't in the best of health when I started it. But after the crash, in which I fractured my cheekbone, I suffered like you cannot imagine possible. I could not take in anything but liquids. I had to race on empty. I had to continue for the sake of the race, for honour and for my teammates. They depended on my prize money. Remember that I still finished second. What I should have done, looking back, was pay my riders what I would have earned out of my own pocket and left the race. Then maybe with my strength rebuilt I could have been competitive in 1976.[7]

1976 Tour de France

Merckx began 1976 by winning his seventh Milan – San Remo[34] but missed winning the Tour of Flanders after falling on the Koppenberg and walking to the top because it was too steep to get back in the saddle.[34] A saddle sore still troubled him and his doctor told him not to ride the Tour.[35]

1977 Tour de France

"It was no different until the [1977] season got into full swing. I prepared well and actually won my first big race, the Tour of the Mediterranean, but as soon as more racing came along my body failed. I kept catching colds and other minor illnesses, where before I rarely did. I started to get little niggling strains and injuries too. Still, I was sixth in the Tour de France that year, and won 17 races. Wouldn't Belgium like to have someone who could finish sixth in the Tour now?

But deep down I knew it was gone."

The 1977 Tour was one too many for Merckx.[34] He suffered on the col de la Madeleine and lost 13 seconds to Hennie Kuiper on Alpe d'Huez. Didi Thurau, a 22-year-old German, beat him in the Pyrenees and bettered him by 50 seconds in the time trial. With Géminiani, his manager in the Fiat team, he had agreed to ride a light start to the season with the aim of a sixth win.[36] But having been outridden by both Thurau and Thévenet, he fell ill. Chany wrote:

By St-Étienne, Merckx had risen to sixth place and began talking of riding the Tour again in 1978, "stupifying those who heard him and splitting his team," according to Chany. The 1977 Tour collapsed into a doping scandal when Zoetemelk was found guilty. Rumours abounded about others. Thévenet won for the second time and four months later said he had succeeded by taking cortisone.[37] Merckx finished sixth, 12m 38s behind. He never did ride in 1978, the year which produced the first victory by Bernard Hinault, the next to win the Tour de France five times.

Giro d'Italia

Merckx won the Giro d'Italia in 1968, 1970, 1972, 1973 and 1974. Following his 1968 win, he said he knew he could win the Tour de France. He won 24 Giro stages in his career. His final victory came in a battle with the Italians Gianbattista Baronchelli, whom he beat by 12 seconds, and Felice Gimondi, who lost by 33 seconds.[38]

World championship victories

Merckx also won the world championship in 1974 for the third time, which only Alfredo Binda and Rik van Steenbergen had done before him, and only Óscar Freire would do after him. Because of his victories in the three most important races of the year, the 1974 Tour de France, the 1974 Giro d'Italia and the 1974 world championship, Merckx won the Triple Crown of Cycling. Since then, only Stephen Roche has been able to do that, in 1987.

Classics victories

Merckx had an impressive list of victories in one-day races, the Classic cycle races, (See Significant victories by race). Among highlights are a record seven victories in Milan – San Remo (absolute record in one classic), two in the Tour of Flanders, three in Paris–Roubaix, five in Liège–Bastogne–Liège (record), and two in the Giro di Lombardia, a total of 19 victories. He also won the world road championship a record three times in 1967, 1971 and 1974, and most of the major classic races, a notable exception being Paris–Tours.

The only rider to have won all the classics is Rik van Looy, Merckx having missed Paris–Tours. A lesser Belgian rider, Noël van Tyghem, won Paris–Tours in 1972[39] and said: "Between us, I and Eddy Merckx have won every classic that can be won. I won Paris–Tours, Merckx won all the rest."[40]

Hour record

Merckx set the hour record in 1972. On 25 October, after he had raced a full road season winning the Tour, Giro and four classics, Merckx covered 49.431 km at high altitude in Mexico City.[41][42]Merckx used a Colnago bicycle to break the record, which had been lightened to a weight of 5.75 kg - lighter than bicycles used in subsequent hour record attempts by Francesco Moser, Graeme Obree and Chris Boardman. Merckx described his ride for the hour record as “the longest of my career”.[43]

The record remained untouched until 1984, when Francesco Moser broke it using a specially designed bicycle, meticulous improvements in streamlining and medical advice from Francesco Conconi. Over 15 years, various racers improved the record to more than 56 km. However, because of the increasingly exotic design of the bikes and position of the rider, these performances were no longer reasonably comparable to Merckx's achievement. In response, the UCI in 2000 required a "traditional" bike to be used. When time trial specialist Chris Boardman, who had retired from road racing and had prepared himself specifically for beating the record, had another go at Merckx's distance 28 years later, he beat it by slightly more than 10 meters (at sea level). To date, only Boardman and Ondřej Sosenka have improved on Merckx's record using traditional equipment.

Track crash

In 1969 Merckx crashed in a derny race in the Blois velodrome towards the end of the season. A pacer and a cyclist fell in front of Merckx's pacer, Fernand Wambst. Wambst died instantly, and Merckx was knocked unconscious. He cracked a vertebra and twisted his pelvis. He said his riding was never the same after the injuries.[8] He frequently adjusted his saddle while riding – including coming down the col de la Faucille on the way to Divonne-les-Bains – and was often in pain, especially while climbing.[7]

Doping

Merckx has condemned doping but he tested positive three times.[2] The first time was in the 1969 Giro d'Italia[8] where he tested positive for the stimulant fencamfamine (Reactivan) at Savona, after leading the race through 16 stages. He was expelled from the Giro. The controversy began to swirl when his test results were not handled in the correct manner; they were released to the press before all parties involved (Merckx and team officials) were notified.[44] Merckx was very upset, and to this day, protests his innocence.[8] He argued there were no counter-experts nor counter-analysis. He said the stage during which he was allegedly using drugs was easy so there was no need. He said:

At the time, the controls weren't reliable and I wasn't able to defend myself. They had started on the analysis and the counter-analysis during the night, without anyone from my team's being present. They had, they said, tried to get my manager, Vincenzo Giacotto, by phone, but he hadn't left his room all evening. The following morning, I was in my racing clothes, ready to leave, when they came to tell me I was positive and therefore excluded from the Giro.[8]

"I've never seen sporting opinion so inflamed," wrote Marcel De Leener from Belgium. "Even members of parliament have got themselves involved in the affair; the Opposition has questioned the minister of public health in the Lower Chamber, the Cabinet is in an uproar, the Foreign Minister has questioned his opposite number in Italy. In the streets, in factories, in offices, in public transport, they talk of little else."[45] The Italian federation stuck by its findings but the Belgians refused to agree and it took four hours of debate in Brussels for the professional section of the Union Cycliste Internationale to quash his sentence. The president of the Fédération Internationale du Cyclisme Professional was Félix Lévitan, organiser of the Tour de France. It was diplomacy and, "let us be frank, hypocrisy too", reported Cycling.[46] The hearing praised the Italians and accepted their evidence; however, Merckx was cleared to ride the Tour.

Prince Albert of Belgium sent a plane to bring him to Belgium.

Merckx was also found positive after winning the Giro di Lombardia in 1973.[8] He had taken Mucantil (Iodinated glycerol).[47]

It was Dr Cavalli, of Molteni, who prescribed it to me a bit lightly [un peu légèrement]. And he admitted his error publicly. Looking back, I can't see why they could disqualify me for such a ridiculous and inoffensive product as norephedrine."[8]

Then he was caught after taking Stimul (pemoline) in the 1977 Flèche Wallonne. Merckx said:

"That, I can't deny. I was positive along with around 15 others. I was wrong to trust a doctor."[8]

In 1974, a Belgian biochemist, Professor Michel Debackere, perfected a test for a group of piperidine stimulant drugs (Lidepran, Meratran, and Ritalin) which were used by pro cyclists. Since they were now detectable, this group of drugs fell out of favor within the pro peloton, and some riders instead used pemoline, another amphetamine-like drug. Then in 1977, Debackere once again developed a new drug test, which could detect pemoline. This test caught three of the biggest names in Belgium: Merckx, Freddy Maertens and Michel Pollentier.[48]

The World Anti-Doping Agency removed norephedrine, phenylpropanolamine, from the list of banned drugs in 2004;[8] however, this drug is currently on the WADA list of banned substances and therefore would garner a suspension of current riders.[49] Merckx said in 2007 that he wanted the Union Cycliste Internationale to give him back his victory: "I was disqualified for taking a syrup which had been taken off the list of forbidden products." At the time, 1973, banned drugs were listed individually; they were later classed by category.

Because of his doping record, the organisers of the 2007 World Championships in Stuttgart asked Merckx to stay away. The decision was criticized in the press and by the UCI.[50] When he confirms his stance against doping, Merckx points out that cycling is unfairly treated compared to other sports.

In the 1990s, he became a friend of Lance Armstrong, and supported him when Armstrong was accused of drug use, stating he rather "believed what Lance told him than what appeared in newspapers". Dr. Michele Ferrari claimed that Merckx introduced him to Armstrong in 1995.[51]

Retirement

Merckx's last victory was an omnium at Zürich on 10 February 1978 with Patrick Sercu, in preparation for the 1978 road season and after a successful yet demanding Six Days saison, winning five out of seven participations, cramped into a period two and a half months, and winning the European Championship Madison in November, all with Sercu as his racing partner in these events. His last race was the Omloop van het Waasland, at Kemzeke on 19 March 1978. He finished 12th. He had already abandoned the Omloop Het Volk, exhausted. His sponsor, the clothing chain, C&A, had supported his team only after long and difficult negotiations[52] and did not intend to continue next season. Merckx told his soigneur, Pierrot De Wit, during their journey home that he had ridden his last race. De Wit argued but Merckx announced his decision at a press conference in Brussels on 18 May 1978. Merckx said:

I am living the most difficult day of my life. I can no longer prepare myself for the Tour de France, which I wanted to ride for a final time as a farewell [apothéose]. After consulting my doctors, I've decided to stop racing.[52]

Bicycle company

On 28 March 1980, Merckx opened a bicycle factory in Brussels, Belgium, called Eddy Merckx Cycles. It quickly gained prominence in the cycling world, and today still is considered one of the most prestigious brands in the world of cycling.[5][53]

Other activities

Merckx is a race commentator on RTBF television.[2] He was coach of the Belgian national cycling team during the mid-90s, and part of the Belgian Olympic Committee. Merckx is still asked to comment as an authority. As such, he was advisor for the Tour of Qatar in 2002. He lives in Meise, Vlaams-Brabant.

Personal life

In December 1967 Merckx married Claudine Acou, a 21-year-old teacher, daughter of Lucien Acou, trainer of the national amateur team.[54][55] The couple married at the town hall in Anderlecht, a suburb of Brussels. The mayor said: "Sometimes I am envious of cycling champions. When they win, there is always a pretty girl to give them a kiss. For my part, no one kisses me when I have a good win, so I'm going to profit from this occasion by kissing the bride now."[54] The witnesses to the marriage were Merckx's manager, Jean van Buggenhout, and a cabinet-maker from Etterbeek, who taught Merckx to ride a bike. The religious service which followed was in Merckx's local church rather than his bride's. Merckx's mother asked the priest, Father Fabien, to celebrate the ceremony in French, a choice that ended up being a contentious issue in Belgium.[n 7] The priest said: "You are now started on a tandem race; believe me, it will not be easy."[54] The couple have two children: a daughter (Sabrina) and a son, Axel, who also became a professional cyclist.[8]

In 1996 Albert II of Belgium King of the Belgians, gave him the title of baron.[2] In 2000 he was chosen Belgian "Sports Figure of the Century". In March 2000 he was received by the Pope in the Vatican.[30]

Merckx is known as a quiet and modest person. Three of his former riders have worked in his bicycle factory and join him during recreational bike tours.[7] Merckx has become an ambassador for the Damien The Leper Society, a foundation named after a Catholic priest, which battles leprosy and other diseases in developing countries. Merckx is an art lover; his favourite artist is René Magritte; a Belgian surrealist.[7]

In May 2004, he had an esophagus operation to cure stomach ache suffered since he was young. He lost almost 30 kg and took up recreational cycling again. In March 2013, Merckx had surgery to add a pacemaker to correct the problem with his heart's rhythm.[56]

Friends and rivals

Because Merckx was so dominant, very few fellow riders wanted to help him to win races, the rivalry was especially strong with other Belgian riders. But Merckx was able to get a few loyal team mates to help him, such as Joseph Bruyere. A star of the winter Six-Day track circuit Patrick Sercu was one of the very few riders that could match Merckx for status, and together they made a very formidable racing partnership, winning several Six-Day races. Merckx was often treated like a royal VIP wherever he went, which sometimes upset other riders, who felt they deserved more respect. Even after his retirement, many subsequent stars still feel over-shadowed by his fame and race results. Merckx befriended Fiorenzo Magni when he began racing for an Italian team.[57]

Career achievements

Grand Tour general classification and World Championship results timeline

| Grand Tour | 1965 | 1966 | 1967 | 1968 | 1969 | 1970 | 1971 | 1972 | 1973 | 1974 | 1975 | 1976 | 1977 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vuelta a España | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | - | - | - | - |

| Giro d'Italia | - | - | 9 | 1 | Dsq | 1 | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 8 | - |

| Tour de France | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | - | 1 | 2 | - | 6 |

| World Championship |

29 | 12 | 1 | 8 | Abn | 29 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 5 | 33 |

Dsq : disqualified for doping

Abn : abandoned

See also

- Cycling records

- Yellow jersey statistics

- Pink jersey statistics

- List of Grand Tour general classification winners

- List of Tour de France general classification winners

- List of Tour de France secondary classification winners

- List of Giro d'Italia general classification winners

- List of Vuelta a España general classification winners

- List of Vuelta a España classification winners

- List of noble families in Belgium

- List of Belgians

Notes

- ↑ The British weekly, Cycling, had only his surname in a report about the 1964 Summer Olympics supplied by a news agency. Needing to add a name, the magazine gambled and referred to him as "Willi Merckx."

- ↑ In 1968 Merckx decided he was not strong enough to ride both the Giro and the Tour, so declined the Tour. The Giro was more important to his team. Merckx has never regretted the decision, not least because that year's race – the "Tour of Health" as it was billed after the death of Tom Simpson the previous year – turned into a slow procession which led the organiser, Félix Lévitan, to accuse journalists who complained of reporting "with tired eyes", after which the journalists went on strike. The 1968 race was ridden by national rather than trade teams, which explains why Faema was less interested.

- ↑ The "Eddy Merckx" velodrome at Mourenx was named in his honour on the 30th anniversary of his first Tour de France victory in 1969. Merckx was present for the ceremony.

- ↑ Tony Rominger (1993) and Laurent Jalabert (1995) have won all 3 jerseys in the Vuelta a España

- ↑ Gaston Defferre was mayor of the city of Marseille for more than 30 years. He was repeatedly linked to dubious business ventures and to the Mafia. The city became Europe's biggest drug-provider in the two decades after the war, culminating in the so-called French Connection. In 1983 he managed to be re-elected with fewer votes than his opponent, having changed the city's voting rules while also minister of the interior.

- ↑ The Ocaña episode ended Bic's sponsorship. The team wasn't pleased that he had raced when he was ill, nor to read in the papers rather than hear from Ocaña that he wouldn't ride the Tour. On the other hand, Ocaña had complained publicly that he had not been paid. The Baron Marcel Bich, owner of Bic, said the money had left him. When he heard that it hadn't reached Ocaña, he dropped out of professional cycling. See Raphaël Géminiani.

- ↑ Brussels is a largely French-speaking enclave in the Dutch-speaking, northern half of Belgium. History, changes in regional prosperity and different attitudes have long separated Belgium more than geographically. Merckx, who is bilingual, was born in one of the few regions of Brussels in which both languages were spoken but more Dutch than French. He then lived in one in which the languages were reversed. His command of both languages and his residence in Brussels meant both communities claimed him. Even his name confuses the situation. Merckx, with its consonants, is a Dutch-sounding name. The contraction of Edouard to "Eddy" is a French customary nickname. Had he been a pure Fleming, it would probably have been shortened to "Ward". Merckx has always resisted saying whether he feels aligned to one community more than another. He finished high in both the Flemish (3rd) and Walloon (4th) editions of the Greatest Belgian contest in 2005.

Citations

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 L'Equipe, Rider database, Eddie Merckx

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 "Eddy MERCKX : Biographie de Eddy MERCKX". Monsieur-Biographie.com. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Vélo, France, November 2000

- ↑ Velonews.com (17 June 2005). "Happy Birthday, Eddy!". Retrieved 13 June 2008.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Friebe 2012, p. 328.

- ↑ Graham Robb (2012-03-16). "Merckx: Half-Man, Half-Bike by William Fotheringham – review". The Guardian (Guardian Media Group). Retrieved 2013-04-13.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 7.7 "Crazy about Belgium, Cycling Greats. Eddy Merckx". Crazyaboutbelgium.co.uk. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 8.8 8.9 8.10 8.11 L'Équipe, France, 13 March 2007

- ↑ Cycling Plus, UK, undated cutting

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Vélo, France, October 2005

- ↑ "Eddy Merckx Olympic Results". sports-reference.com. Retrieved 22 August 2014.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 12.4 "L'Equipe, Cycling Portfolio – Eddy Merckx". L'Équipe. France. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Cycling, UK, 9 September 1967, p5

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Cycling, UK, 23 September 1967, p19

- ↑ L'Équipe, France, 3 July 2003

- ↑ Thonon, Pierre (1970). Eddy Merckx du maillot arc en ciel au maillot jaune. De Schorpioen.

- ↑ Ollivier 2001, p. 14.

- ↑ Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 592.

- ↑ L'Équipe, France, 10 July 1970

- ↑ "Historical results – Tour de France". Cycling hall of fame. Retrieved 28 September 2009.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Merckx 1971.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "Eurosport, Cyclisme, One day in the Tour". Eurosport.fr. Retrieved 17 July 2010."Trek N Ride".

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 610.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 "BikeRaceInfo Oral History – Celestino Vercelli". Bikeraceinfo.com. 2 June 1969. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 616.

- ↑ Augendre, Jacques (1986), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p64

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Memoire du Cyclisme 1972 Tour de France". Memoire-du-cyclisme.net. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Merckx 1972.

- ↑ L'Équipe, France, 24 July 1970

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 Procycling, UK, May 2000

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 639.

- ↑ Ollivier 2001, p. 21.

- ↑ Augendre, Jacques (1986), Le Tour de France, Panorama d'un Siècle, Société du Tour de France, France, p67

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 "Eddy Merckx (6)". Memoire du Cyclisme. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Le Net du Cyclisme – 1976

- ↑ Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 664.

- ↑ Cazeneuve & Chany 2011, p. 672.

- ↑ Vanwalleghem 2000.

- ↑ "wedstrijdfichestatscdet.php?wedstrijdid=1102&landid=17 Cykelsiderne. Database. Sejre/Etaper pr. land Paris – Tours Belgien". Cykelsiderne.net. 27 June 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "The Independent, Friday 6th July, 2007, Tour de France: Alternative view of the ultimate road race". The Independent (UK). 6 July 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Cycling Passion – Eddy Merckx Hour record

- ↑ Clemitson, Suze (19 September 2014). "Why Jens Voigt and a new group of cyclists want to break the Hour record". The Guardian. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ Clemitson, Suze (19 September 2014). "Why Jens Voigt and a new group of cyclists want to break the Hour record". theguardian.com. Retrieved 19 September 2014.

- ↑ "Cycling Revealed, Timeline, 1969, 52nd Giro d'Italia 1969 By Barry Boyce, Merckx DQ'd". Cyclingrevealed.com. 8 June 1969. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Cycling, UK, 14 June 1969, p21

- ↑ Cycling, UK, 21 June 1969, p14

- ↑ "Iodinated glycerol". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "MedLibrary, Doping at the Tour de France, Steroids and allied drugs". Medlibrary.org. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ "List of Prohibited Substances and Methods". WADA. Retrieved 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Cyclingnews.com (26 September 2007). "Eddy Merckx joins list of unwelcome people in Stuttgart". Retrieved 28 September 2007.

- ↑ An Interview With Dr. Michele Ferrari, part two, 2003, Tim Maloney / Cyclingnews European Editor

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 L'Équipe, France, undated cutting

- ↑ "website of Eddy Merckx bicycle factory". Eddymerckx.be. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 54.2 Cycling, UK, 16 December 1967, p22

- ↑ Lucien Acou at Dutch Wikipedia

- ↑ "Eddy Merckx fitted with a pacemaker to control heart issues — VeloNews.com". Velonews.competitor.com. 2013-03-22. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

- ↑ "Giro d'Italia Hall of Fame inducts Eddy Merckx as its first member — VeloNews.com". Velonews.competitor.com. 2012-04-25. Retrieved 2013-10-30.

References

- Cazeneuve, Thierry; Chany, Pierre (2011). La fabuleuse histoire du Tour de France [The Story of the Tour de France] (in French). Paris: La Martinière. ISBN 978-2-7324-4792-6. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Friebe, Daniel (2012). Eddy Merckx: The Cannibal. London: Ebury Press. ISBN 978-0-09-194314-1. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Merckx, Eddy (1972). Plus d'un tour dans mon sac: Mes carnets de route 1972 (in French). Arts et Voyages. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Merckx, Eddy (1971). Jeuniau, Marc, ed. Mes carnets de route (in French). Paris: Éditions Albin Michel. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Ollivier, Jean-Paul (2001). Maillot Jaune: The Tour de France Yellow Jersey. Ingram Pub Services. ISBN 978-1-884737-98-5. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Vanwalleghem, Rik (2000). Eddy Merckx: The Greatest Cyclist of the 20th Century. Boulder, Colorado: VeloPress. ISBN 978-1-884737-72-5. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

Further reading

- Fotheringham, William (2012). Merckx: Half Man, Half Bike. London: Yellow Jersey Press. ISBN 978-0-224-09195-4. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- Vanwalleghem, Rik (1989). Eddy Merckx, mijn levensverhaal : de ware selfmade man als wielrenner en als zakenman (in Dutch). Helios. ISBN 90-289-1465-X.

- Rosier, Erik (1973). Eddy Merckx (in Dutch). Franco-Suisse. OCLC 57423874.

- Cornand, Jan and Blancke, Andre (1975). Hoe Merckx de tour verloor / wielerseizoen 1975 van A tot Z (in Dutch). Het Volk.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eddy Merckx. |

- Eddy Merckx profile at Cycling Archives

| Records | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Ole Ritter |

UCI hour record (49.431 km) 25 October 1972 – 27 October 2000 |

Succeeded by Chris Boardman |

|