Economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

| Economy of Democratic Republic of Congo | |

|---|---|

Kinshasa, capital and economic center of the Democratic Republic of the Congo | |

| Currency | Congolese Franc (CDF) |

| Calendar Year | |

Trade organisations | AU, African Development Bank, SADC, World Bank, IMF, WTO, Group of 77 |

| Statistics | |

| GDP |

Rank: 114 (2012 est.) |

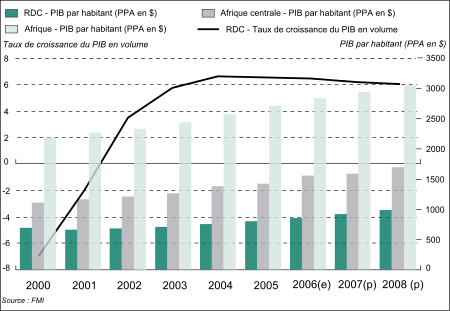

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita |

$694 (PPP) (2014 est.) Rank: 186 (2012 est.) |

GDP by sector |

agriculture (44.2%) industry (22.6%) services (33.1%) (2012 est.) |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | 70% (2011 est.) |

Labour force | 35.86 million (2012 est.) |

Labour force by occupation | N/A |

| Unemployment | N/A |

Main industries | mining (copper, cobalt, gold, diamonds, coltan, zinc, tin, tungsten), mineral processing, consumer products (including textiles, plastics, footwear, cigarettes, processed foods, beverages), metal products, lumber, cement, commercial ship repair |

| 183rd[1] | |

| External | |

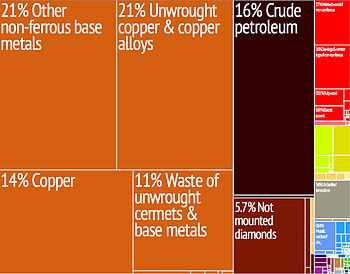

| Exports |

|

Export goods | gold, diamonds, copper, cobalt, coltan, zinc, tin, tungsten, crude oil, wood products, coffee |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports |

|

Import goods | machinery, transportation equipment, fuel, food |

Main import partners |

|

Gross external debt |

|

| Public finances | |

| Revenues | $5.941 billion (2014 est.) |

| Expenses | $5.537 billion (2012 est.) |

Foreign reserves |

|

Sparsely populated in relation to its area, the Democratic Republic of the Congo is home to a vast potential of natural resources and mineral wealth. Its untapped deposits of raw minerals are estimated to be worth in excess of US$24 trillion. Despite this, the economy has declined drastically since the mid-1980s.[4]

At the time of its independence in 1960, the Democratic Republic of the Congo was the second most industrialized country in Africa after South Africa. It boasted a thriving mining sector and its agriculture sector was relatively productive.[4] Since then, corruption, war and political instability have been a severe detriment to further growth, today leaving DRC with a GDP per capita among the world's lowest.

Economic Implications of Conflicts

The two recent conflicts (the First and Second Congo Wars), which began in 1996, have dramatically reduced national output and government revenue, have increased external debt, and have resulted in deaths of more than five million people from war, and associated famine and disease. Malnutrition affects approximately two thirds of the country's population.[5]

Agriculture is the mainstay of the economy, accounting for 57.9% of GDP in 1997. In 1996, agriculture employed 66% of the work force.

Rich in minerals, the Democratic Republic of the Congo has a difficult history of predatory mineral extraction, which has been at the heart of many struggles within the country for many decades, but particularly in the 1990s. The economy of the third largest country in Africa relies heavily on mining. However, much economic activity occurs in the informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data.[6]

In 2006 Transparency International ranked the Democratic Republic of the Congo 156 out of 163 countries in the Corruption Perception Index, tying Bangladesh, Chad, and Sudan with a 2.0 rating.[7] President Joseph Kabila established the Commission of Repression of Economic Crimes upon his ascension to power in 2001.[8]

Economic history

Zaire

After the Congo crisis Mobutu arose as the country's sole ruler and stabilized the country politically. Economically, however, the situation continued to decline and by 1979 the purchasing power was only 4% of that from 1960.[9] Starting in 1976 the IMF provided stabilizing loans to the dictatorship. Much of the money was embezzled by Mobutu and his circle.[9] This was not a secret as the 1982 report by IMF’s envoy Erwin Blumenthal documented. He stated, it is “alarmingly clear that the corruptive system in Zaire with all its wicked and ugly manifestations, its mismanagement and fraud will destroy all endeavors of international institutions, of friendly governments, and of the commercial banks towards recovery and rehabilitation of Zaire’s economy".[10] Blumenthal indicated that there was “no chance” that creditors would ever recover their loans. Yet the IMF and the World Bank continued to lend money that was either embezzled, stolen, or "wasted on elephant projects".[11] “Structural adjustment programmes” implemented as a condition of IMF loans cut support for health care, education, and infrastructure.[9]

1990s

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) Trust Fund for the Congo. Poor infrastructure, an uncertain legal framework, corruption, and lack of openness in government economic policy and financial operations remain a brake on investment and growth. A number of International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank missions have met with the new government to help it develop a coherent economic plan but associated reforms are on hold.

Faced with continued currency depreciation, the government resorted to more drastic measures and in January 1999 banned the widespread use of U.S. dollars for all domestic commercial transactions, a position it later adjusted. The government has been unable to provide foreign exchange for economic transactions, while it has resorted to printing money to finance its expenditure. Growth was negative in 2000 because of the difficulty of meeting the conditions of international donors, continued low prices of key exports, and post-coup instability. Although depreciated, congolese francs have been stable for few years (Ndonda, 2014)

2000s

Conditions improved in late 2002 with the withdrawal of a large portion of the invading foreign troops. A number of IMF and World Bank missions have met with the government to help it develop a coherent economic plan, and President Kabila has begun implementing reforms.

Special Economic Zone

The DRC is embarking on the establishment of special economic zones (SEZ) to encourage the revival of its industry. The first SEZ was planned to come into being in 2012 in N'Sele, a commune of Kinshasa, and will focus on agro-industries. The Congolese authorities also planned to open another zone dedicated to mining (Katanga) and a third dedicated to cement (in the Bas-Congo).[12]

Implications of Instability on Economy

Ongoing conflicts dramatically reduced government revenue increased external debt. As Reyntjens wrote, “Entrepreneurs of insecurity are engaged in extractive activities that would be impossible in a stable state environment. The criminalization context in which these activities occur offers avenues for considerable factional and personal enrichment through the trafficking of arms, illegal drugs, toxic products, mineral resources and dirty money.”16

International Relations

International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD) Trust Fund for the Congo. Poor infrastructure, an uncertain legal framework, corruption, and lack of openness in government economic policy and financial operations remain a brake on investment and growth. A number of International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank missions have met with the new government to help it develop a coherent economic plan but associated reforms are on hold.

Faced with continued currency depreciation, the government resorted to more drastic measures and in January 1999 banned the widespread use of U.S. dollars for all domestic commercial transactions, a position it later adjusted. The government has been unable to provide foreign exchange for economic transactions, while it has resorted to printing money to finance its expenditure. Growth was negative in 2000 because of the difficulty of meeting the conditions of international donors, continued low prices of key exports, and post-coup instability.

World Bank

Ease of Doing Business Rank (EDBR)

The Democratic Republic of Congo ranks 183 on the low end of the ease of doing business scale as ranked by the World Bank. This measures the difficulties of starting a business, enforcing contracts, paying taxes, resolving insolvency, protecting investors, trading across borders, getting credit, getting electricity, dealing with construction permits and registering property (World Bank 2014:8). [13]

Sectors

Agriculture

Agriculture is the mainstay of the economy, accounting for 57.9% of the GDP in 1997. Main cash crops include coffee, palm oil, rubber, cotton, sugar, tea, and cocoa. Food crops include cassava, plantains, maize, groundnuts, and rice. In 1996, agriculture employed 66% of the work force.

Fishing

The Democratic Republic of Congo also possesses 50 percent of Africa’s forests and a river system that could provide hydro-electric power to the entire continent, according to a United Nations report on the country’s strategic significance and its potential role as an economic power in central Africa.[14] Fish are the single most important source of animal protein in the DRC. Total production of marine, river, and lake fisheries in 2003 was estimated at 222,965 tons, all but 5,000 tons from inland waters. PEMARZA, a state agency, carries on marine fishing.

Forestry

Forests cover 60 percent of the total land area. There are vast timber resources, and commercial development of the country’s 61 million hectares (150 million acres) of exploitable wooded area is only beginning. The Mayumbe area of Bas-Congo was once the major center of timber exploitation, but forests in this area were nearly depleted. The more extensive forest regions of the central cuvette and of the Ubangi River valley have increasingly been tapped.

Roundwood removals were estimated at 72,170,000 m3 in 2003, about 95 percent for fuel. Some 14 species are presently being harvested. Exports of forest products in 2003 totalled $25.7 million. Foreign capital is necessary in order for forestry to expand, and the government recognizes that changes in tax structure and export procedures will be needed to facilitate economic growth.

Mining

Rich in minerals, the DRC has a difficult history of predatory mineral extraction, which has been at the heart of many struggles within the country for many decades, but particularly in the 1990s. Although the economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the second largest country in Africa has historically relied heavily on mining, this is no longer reflected in the GDP data as the mining industry has suffered from long-term "uncertain legal framework, corruption, and a lack of transparency in government policy." The informal sector .[6]

In her book entitled The Real Economy of Zaire, MacGaffey described a second, often illegal economy, "system D," which is outside the official economy (MacGaffey 1991:27).[15] and therefore is not reflected in the GDP.

exploitation of mineral substances as MIBA EMAXON and De Beers The economy of the second largest country in Africa relies heavily on mining. The Congo is the world's largest producer of cobalt ore,[16] and a major producer of copper and industrial diamonds. The Congo has 70% of the world’s coltan, and more than 30% of the world’s diamond reserves.,[17] mostly in the form of small, industrial diamonds. The coltan is a major source of tantalum, which is used in the fabrication of electronic components in computers and mobile phones. In 2002, tin was discovered in the east of the country, but, to date, mining has been on a small scale.

[18] Smuggling of the conflict minerals, coltan and cassiterite (ores of tantalum and tin, respectively), has helped fuel the war in the Eastern Congo.

Copper and Cobalt

Katanga Mining Limited, a London-based company, owns the Luilu Metallurgical Plant, which has a capacity of 175,000 tonnes of copper and 8,000 tonnes of cobalt per year, making it the largest cobalt refinery in the world. After a major rehabilitation program, the company restarted copper production in December 2007 and cobalt production in May 2008.[19]

Informal sector

Much economic activity occurs in the informal sector and is not reflected in GDP data.[6]

Transport

Ground transport in the Democratic Republic of Congo has always been difficult. The terrain and climate of the Congo Basin present serious barriers to road and rail construction, and the distances are enormous across this vast country. Furthermore, chronic economic mismanagement and internal conflict has led to serious under-investment over many years.

On the other hand, the Democratic Republic of Congo has thousands of kilometres of navigable waterways, and traditionally water transport has been the dominant means of moving around approximately two-thirds of the country.

See also

- Democratic Republic of the Congo

- List of companies based in the Democratic Republic of the Congo

- Mining industry of the Democratic Republic of the Congo

References

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

This article incorporates public domain material from websites or documents of the CIA World Factbook.

- ↑ Doing Business in Congo, Dem. Rep. 2013 (Report). World Bank. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- ↑ "Export Partners of Democratic Republic of Congo". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ "Import Partners of Democratic Republic of Congo". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Centre National d'Appui au Développement et à la Participation Paysanne CENADEP (2009-10-23). Province orientale :le diamant et l'or quelle part dans la reconstruction socio - économique de la Province ? (Report).

- ↑ Seema Shekhawat (January 2009). Governance Crisis and Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (PDF) (Report). Working Paper No. 6. Mumbai: Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Dublin - Research and Markets

- ↑ J. Graf Lambsdorff (2006). "Corruption Perceptions Index 2006". Transparency International. Retrieved 2008-01-21.

- ↑ Werve, Jonathan (2006). The Corruption Notebooks 2006. p. 57.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 David van Reybrouck. Congo: The Epic History of a People. HarperCollins, 2012. p. 374ff. ISBN 978-0-06-220011-2.

- ↑ Georges Nzongola-Ntalaja. The Crisis in Zaire: Myths and Realities. Africa World Press, 1986. p. 226. ISBN 0-86543-023-3.

- ↑ Aikins Adusei (30 May 2009). "IMF and World Bank: Agents of Poverty or Partners of Development?". Modern Ghana. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- ↑ Le "paradis" où le droit fera la loi, L'Echo, novembre 2010 (French)

- ↑ Economy Profile: Democratic Republic of Congo (PDF) (Report). Washington, DC: [World Bank: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development www.worldbank.org]. 2013. Retrieved 2013.

- ↑ Democratic Republic of the Congo economic and strategic significance

- ↑ Janet MacGaffey (1991). The Real Economy of Zaire: The Contribution of Smuggling and Other Unofficial Activities to National Wealth. London: James Currey. p. 175.

- ↑ "Cobalt: World Mine Production, By Country". Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- ↑ "DR Congo poll crucial for Africa" BBC News. 16 November 2006.

- ↑ Polgreen, Lydia (16 November 2008). "Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

- ↑ "Katanga Project Update and 2Q 2008 Financials, Katanga Mining Limited,". 8 12 08. Check date values in:

|date=(help)

External links

- Janet MacGaffey (1991). The Real Economy of Zaire: The Contribution of Smuggling and Other Unofficial Activities to National Wealth. London: James Currey. p. 175.

- Seema Shekhawat (January 2009). Governance Crisis and Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (PDF) (Report). Working Paper No. 6. Mumbai: Centre for African Studies, University of Mumbai. Retrieved 23 March 2013.

- Economy of the Democratic Republic of the Congo at DMOZ

- Democratic Republic of the Congo latest trade data on ITC Trade Map

- First Blood Diamonds, Now Blood Computers? by Elizabeth Dias, Time Magazine, 24 July 2009

- Oasis Kodila Tedika et Francklin Kyayima Muteba, The sources of growth in DRC before independence. A cointegration analysis, CRE Working paper, n°02/10, juin 2010

- Exenberger, Andreas/Hartmann, Simon (2007): The Dark Side of Globalization. The Vicious Cycle of Exploitation from World Market Integration: Lesson from the Congo, Working Papers in Economics and Statistics 31-2007 7yjmyry

- Doing Business in Congo, Dem. Rep. 2013 (Report). World Bank. Retrieved 2013-03-25.

- Polgreen, Lydia (16 November 2008). "Congo's Riches, Looted by Renegade Troops". The New York Times. Retrieved 27 March 2010.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||