Economy of Venezuela

| Economy of Venezuela | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Currency | Bolívar fuerte (VEF) |

| calendar | |

Trade organisations | WTO, OPEC, Unasur, MERCOSUR, ALBA |

| Statistics | |

| GDP |

$402.1 (2012, PPP) $338 billion (2012, Real)[1][2] |

| GDP rank | 31st (nominal) / 33rd (PPP) |

GDP growth |

|

GDP per capita | $13,200 (2012, PPP)[1] |

GDP by sector | agriculture: 4.1%, industry: 34.9%, services: 61.1% (2010 est.) |

|

| |

Population below poverty line | 27.3% (2013 est.)[7] |

Labour force | 13.7 million (2012 est.) |

Labour force by occupation | agriculture: 7.3%, industry: 21.8%, services: 70.9% (2011 est.) |

| Unemployment | 7.9% (Jan. 2015)[8] |

Main industries | Petroleum, construction materials, food processing, iron ore mining, steel, aluminum; motor vehicle assembly, real estate, tourism and ecotourism |

| 182nd[9] | |

| External | |

| Exports | $96.9 billion (2012)[1] |

Export goods | Petroleum, chemicals, agricultural products, basic manufactures |

Main export partners |

|

| Imports | $56.7 billion (2012)[1] |

Import goods | food, clothing, cars, technological items, raw materials, machinery and equipment, transport equipment, construction material |

Main import partners |

|

| Public finances | |

| 49% of GDP (2012 est.) | |

| Revenues | $116.3 billion |

| Expenses | $175.3 billion (2012 est.); including capital expenditures of $2.6 billion (2012 est.) |

|

Standard & Poor's:[12] Moody's:[13] CCC Outlook: Negative | |

Foreign reserves |

|

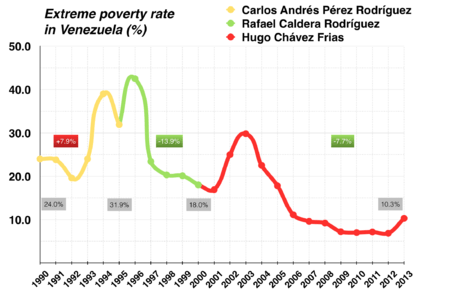

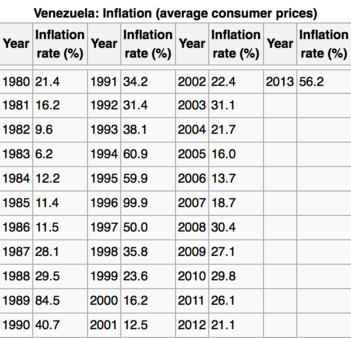

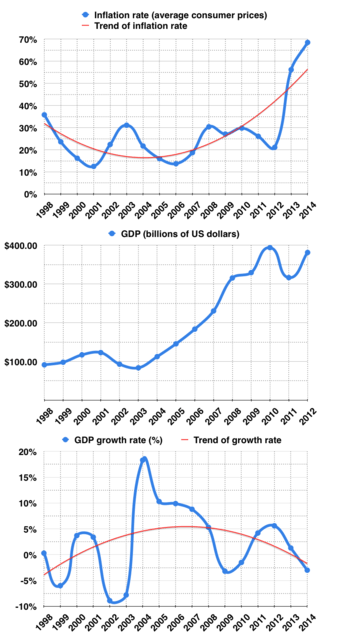

The economy of Venezuela is largely based on the petroleum sector and manufacturing.[16] Revenue from petroleum exports accounts for more than 50% of the country's GDP and roughly 95% of total exports. Venezuela is the fifth largest member of OPEC by oil production. From the 1950s to the early 1980s the Venezuelan economy experienced a steady growth that attracted many immigrants, with the nation enjoying the highest standard of living in Latin America. During the collapse of oil prices in the 1980s the economy contracted, and inflation skyrocketed to reach peaks of 84% in 1989 and 99% in 1996, three years prior to Hugo Chávez taking office. With high oil prices and rising government expenditures, Venezuela's economy grew by 9% in 2007.

Manufacturing contributed 17% of GDP in 2006. Venezuela manufactures and exports heavy industry products such as steel, aluminium and cement, with production concentrated around Ciudad Guayana, near the Guri Dam, one of the largest in the world and the provider of about three-quarters of Venezuela's electricity. Other notable manufacturing includes electronics and automobiles, as well as beverages, and foodstuffs. Agriculture in Venezuela accounts for approximately 3% of GDP, 10% of the labor force, and at least one-fourth of Venezuela's land area. Venezuela exports rice, corn, fish, tropical fruit, coffee, pork, and beef. The country is not self-sufficient in most areas of agriculture.

In spite of strained relations between the two countries, the United States is Venezuela's most important trading partner. U.S. exports to Venezuela include machinery, agricultural products, medical instruments, and cars. Venezuela is one of the top four suppliers of foreign oil to the United States. About 500 U.S. companies are represented in Venezuela.[16] According to Central Bank of Venezuela, the government received from 1998 to 2008 around 325 billion USD through oil production and export in general,[17] and according to the International Energy Agency, to June 2010 has production of 2.2 million barrels per day, 800,000 of which go to the United States of America.[18]

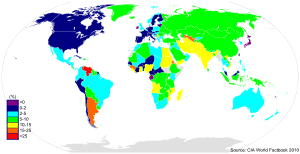

Since Hugo Chávez imposed stringent currency controls in 2003 in an attempt to prevent capital flight,[19] there have been a series of currency devaluations, disrupting the economy.[20] Price controls, expropriation, and other government policies have caused severe shortages of food and other goods, including medical supplies.[21] Venezuela has one of the highest inflation rates in the world averaging 29.1% in 2010, according to the CIA World Fact Book.[22]

History

1922 - 1964

When oil was discovered at the Maracaibo strike in 1922, Venezuela's dictator, Juan Vicente Gómez, allowed US oil companies to write Venezuela's petroleum law.[23] But oil history was made in 1943 when Standard Oil of New Jersey accepted a new agreement in Venezuela based on the 50-50 principle, "a landmark event."[24] Terms even more favorable to Venezuela were negotiated in 1945, after a coup brought to power a left-leaning government that included Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonso.

From the 1950s to the early 1980s the Venezuelan economy was the strongest in South America. The continuous growth during that period attracted many immigrants.

In 1958 a new government again included Pérez Alfonso, who devised a plan for the international oil cartel that would become OPEC.[25] In 1973 Venezuela voted to nationalize its oil industry outright, effective 1 January 1976, with Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) taking over and presiding over a number of holding companies; in subsequent years, Venezuela built a vast refining and marketing system in the US and Europe.[26]

During Pérez Jimenez' dictatorship from 1952 to 1958, Venezuela enjoyed remarkably high GDP growth, so that in the late 1950s Venezuela's real GDP per capita almost reached West Germany's. On 1950, Venezuela was the world's 4th largest wealthiest nation per capita[27] However, from 1958/1959 onward, Romulo Betancourt (president from 1959 to 1964) inherited an enormous internal and external debt caused by rampant public spending during the dictatorship. Nevertheless, he managed to balance Venezuela's public budget and initiate an unsuccessful agrarian reform.[28]

1960s - 1990s

Buoyed by a strong oil sector in the 1960s and 1970s,Venezuela's governments were able to maintain social harmony by spending fairly large amounts on public programs including health care, education, transport, and food subsidies. Literacy and welfare programs benefited tremendously from these conditions.[29] Because of the oil wealth, Venezuelan workers "enjoyed the highest wages in Latin America."[30] This situation was reversed when oil prices collapsed during the 1980s. The economy contracted, and the number of people living in poverty rose from 36% in 1984 to 66% in 1995.[31] The country suffered a severe banking crisis (Venezuelan banking crisis of 1994).

When world oil prices collapsed in the 1980s, the economy contracted and inflation levels (consumer price inflation) rose, remaining between 6 and 12% from 1982 to 1986.[32][33] In the late 80s and early 90s inflation rose to around 30 - 40% annually, with a 1989 peak of 84%.[33] The mid-1990s saw annual rates of 50-60% (1993 to 1997) with an exceptional peak in 1996 at 99.88%.[33] Subsequently inflation then remained in a range of around 15% to 30% until the end of Hugo Chávez's presidency.[33]

By 1998, the economic crisis had grown even worse. Per capita GDP was at the same level as 1963 (after adjusting 1963 dollar to 1998 value), down a third from its 1978 peak; and the purchasing power of the average salary was a third of its 1978 level.[34]

1999 - 2012

Hugo Chávez was elected president in December 1998 and took office in February 1999. In 2000, oil prices soared, offering Chavez funds not seen since Venezuela's economic collapse since the 1980s.[32] Chavez then used economic policies that were more socialistic than those of his predecessors, using populist approaches with oil funds that made Venezuela's economy dependent on high oil prices.[32] Chavez also played a leading role within OPEC to reinvigorate that organisation and obtain members' adherence to lower production quotas designed to drive up the oil price. Venezuelan oil minister Alí Rodríguez Araque's announcement in 1999 that his country would respect OPEC production quotas marked "a historic turnaround from the nation's traditional pro-US oil policy." [35]

In the first four years of the Chávez presidency, the economy grew at first (1999–2001), then contracted from 2001 - 2003 to GDP levels similar to 1997, at first because of low oil prices, then because of the turmoil caused by the 2002 coup attempt and the 2002-2003 business strike. Other factors in the decline were an exodus of capital from the country, and a reluctance of foreign investors. Gross Domestic Product was 50.0 trillion bolivares in 1998. At the bottom of the recession, 2003, it was 42.4 trillion bolivares (in constant 1998 bolivares).[36] However, with a calmer political situation in 2004, GDP rebounded 50.1 trillion bolivares, and rose to 66.1 trillion bolivares in 2007 (both in constant 1998 bolivares).[37]

The government sought international assistance to finance reconstruction after massive flooding and landslides in December 1999 caused an estimated US$15 billion to $20 billion in damage.

The hardest hit sectors in the worst recession years, 2002–2003, were construction (−55.9%), petroleum (−26.5%), commerce (−23.6%) and manufacturing (−22.5%). The drop in the petroleum sector was caused by adherence to the OPEC quota established in 2002 and the virtual cessation of exports during the PdVSA-led Venezuelan general strike of 2002-2003. The non-petroleum sector of the economy contracted by 6.5% in 2002. The bolivar, which has been suffering from serious inflation and devaluation relative to international standards since the late 1980s,[38] continued to weaken.

The inflation rate, as measured by consumer price index, was 35.8% in 1998, falling to a low of 12.5% in 2001 and rising to 31.1% in 2003. Historically, the highest yearly inflation was 99.9% in 1996. On 23 January 2003, in an attempt to support the bolivar and bolster the government's declining level of international reserves, as well as to mitigate the adverse impact from the oil industry work stoppage on the financial system, the Ministry of Finance and the central bank suspended foreign exchange trading. On 6 February, the government created CADIVI, a currency control board charged with handling foreign exchange procedures. The board set the US dollar exchange rate at 1,596 bolivares to the dollar for purchases and 1,600 to the dollar for sales.

The housing market in Venezuela has shrunk significantly in recent years. Developers have avoided Venezuela due to the massive number of companies who have had their property expropriated by the government.[39] According to the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal, Venezuela has the weakest property rights in the world, scoring only 5.0 on a scale of 100; expropriation without compensation is common.[40] The shortage of housing is so significant that in 2007, a group of squatters occupied Centro Financiero Confinanzas, a cancelled economic center that was supposed to symbolize Venezuela's growing economy.[41] However, this building still does symbolize the economy of Venezuela under Chávez as it hasn't been able to fully recover to the same heights since the building was abandoned nearly twenty years ago.[42] There are currently thousands of occupants still inside of the complex today.

The Venezuelan economy shrank 5.8 percent in the first three months of 2010 compared to the same period last year[43] and now has the highest inflation rate in Latin America (30.5%).[43] President Hugo Chávez expressed optimism that Venezuela would soon emerge from recession,[43] despite the International Monetary Fund forecasts showing that Venezuela would be the only country in the region to remain in recession that year.[44] The IMF qualified as "delayed and weak" the economic recovery of Venezuela in comparison with other countries of the region.[45] However, after Chavez's death in early 2013, Venezuela's economy continued to fall into an even greater recession.

2013 - present

According to the 2013 Global Misery Index Scores, Venezuela was ranked as the top spot globally with the highest misery index score,[46] while the Heritage Foundation ranked Venezuela 175th out of 178 countries in economic freedom, classifying it as a "Repressed" economy.[47] In early 2013, Venezuela devalued its currency due to growing shortages in the country.[48] The shortages included necessities such as toilet paper, milk, and flour.[49] Fears rose so high due to the toilet paper shortage that the government occupied a toilet paper factory.[50] In late 2013, Venezuela's inflation rates increased even higher, to 54.3%,[51] and forecasts from the International Monetary Fund show Venezuela as one of the slowest-growing economies in Latin America for 2013.[52] Black market estimates that most Venezuelans have to use for purchases have risen to almost ten times the official exchange rate.[53]

Venezuela's bond ratings have also decreased multiple times in 2013 due to decisions by President Nicolás Maduro. One of his decisions was to force stores and their warehouses to sell all of their products, which may lead to even more shortages in the future.[54] President Maduro also created "a freeze on commercial rents at rates more than 50 percent lower than they had been at some malls" which resulted with Venezuela's malls and retail industry losing 75% of their incomes.[55] Venezuela's outlook has also been deemed negative by most bond-rating services.[56] According to a Johns Hopkins University professor, Venezuela had a 297% implied inflation rate for 2013.[57]

As of early 2014, many companies have either slowed or stopped operation due to the lack of hard currency in the country. Ford Motor Co. is one of the largest companies that has slowed production in Venezuela due to its lack of foreign currency for supplies. Because of recent economic uncertainties, Ford also believes that there will be a significant devaluation of the bolívar as well.[58] In January 2014, many airlines, including Air Canada, Air Europa, American Airlines, Copa Airlines, TAME, TAP Airlines, and United Airlines, suspended international flights operating in Venezuela because the government has been restricting access to the U.S. dollar.[59][60] There are talks among airlines of canceling even more international flights out of the country since Venezuela still owes foreign airlines nearly $3.3 billion USD.[61] Venezuela has also dismantled CADIVI, a government body in charge of currency exchange. CADIVI was known for holding money from the private sector and suspected to be corrupt.[62] In February, Toyota, the largest automobile manufacturer, has stopped production indefinitely in Venezuela due to an 87% drop in automotive sales.[63] General Motors Company has also suspended production after losing $162 million USD and stated that they "saw no horizon or resolutions to business operations in Venezuela".[64] In February 2014, doctors at University of Caracas Medical Hospital stopped performing surgeries due to the lack of supplies, even though nearly 3,000 people require surgery.[65] The government's currency policy has made it difficult to import drugs and other medical supplies.[66] The Venezuelan government stopped publishing medical statistics in 2010 and does not supply enough dollars for medical supplies; doctors say that 9 of 10 of large hospitals have only 7% of required supplies with private doctors reporting many patients that are "impossible" to count are dying from easily treated illnesses due to the "downward sliding economy".[67]

In March 2014, the executive director of the Venezuelan Association of Hospitals and Clinics explained how in less than a month, shortages of 53 medical products rose to 109 products and explained how the CADIVI system is to blame since 86% of supplies are imported.[68] Both public and private sector hospitals have only about 2 months of supplies with private sector hospitals claiming they owe suppliers US$15 billion in order to pay for debts.[69]

In April 2014, the International Monetary fund said that activity in Venezuela is uncertain but may continue to slow saying that "loose macroeconomic policies have generated high inflation and a drain on official foreign exchange reserves". The IMF suggested that "more significant policy changes are needed to stave off a disorderly adjustment".[70] Venezuela was also the only country in the world that the International Monetary Fund predicts will experience a drop in GDP. They predicted Venezuela's GDP to contract at a rate around -.5% for the year 2014.[71] Coca-Cola Company announced that Venezuela's currency controls created "adverse impact" on its operations expecting a "negative impact of 7% in their overall performance this year from the impact of currency exchange".[72] El Tiempo reported that some goods in Venezuelan stores had a 114% to 425% premium due to "under the table" negotiations between the Venezuelan government and traders.[73] El Nuevo Herald reported that SEBIN has cut down its work due to the lack of money limiting their work to the monitoring of "potential external threats" and asking for Cuban intelligence agents to return to Venezuela.[74]

In May 2014, the Central Bank of Venezuela announced that the shortage rate of automobiles was at 100%.[75] Citibank believed " that the economy has little prospect of improvement" and that the state of the economy was a "disaster".[76] General Motors Venezolana stopped automotive production after 65 years of service due to a lack of supplies.[77][78]

Sectors

Petroleum and other resources

Venezuela is a major producer of petroleum products, which remain the keystone of the Venezuelan economy. The International Energy Agency shows how Venezuela's oil production has fallen in the last years, producing only 2,300,000 barrels (370,000 m3) daily, down from 3.5 million in 1998, but with the recent currency devaluation the oil incomes will double its value in local currency.[79]

A range of other natural resources, including iron ore, coal, bauxite, gold, nickel, and diamonds, are in various stages of development and production. In April 2000, Venezuela's President decreed a new mining law, and regulations were adopted to encourage greater private sector participation in mineral extraction. During Venezuela's economic crisis, the rate of gold excavated fell 64.1% between February 2013 and February 2014 and iron production dropped 49.8%.[80]

Venezuela utilizes vast hydropower resources to supply power to the nation's industries. The national electricity law is designed to provide a legal framework and to encourage competition and new investment in the sector. After a 2-year delay, the government is proceeding with plans to privatize the various state-owned electricity systems under a different scheme than previously envisioned.

Manufacturing

Manufacturing contributed 15% of GDP in 2009. The manufacturing sector is experiencing severe difficulties, amidst lack of investment and accusations of mismanagement.[81][82] Venezuela manufactures and exports steel, aluminium, transport equipment, textiles, apparel, beverages, and foodstuffs. It produces cement, tires, paper, fertilizer, and assembles cars both for domestic and export markets.

Agriculture

Agriculture in Venezuela accounts for approximately 3% of GDP, 10% of the labor force, and at least a quarter of Venezuela's land area. Venezuela exports rice, corn, fish, tropical fruit, coffee, beef, and pork. The country is not self-sufficient in most areas of agriculture. Venezuela imports about two-thirds of its food needs. In 2002, U.S. firms exported $347 million worth of agricultural products, including wheat, corn, soybeans, soybean meal, cotton, animal fats, vegetable oils, and other items to make Venezuela one of the top two U.S. markets in South America. The United States supplies more than one-third of Venezuela's food imports. Recent government policies have led to problems with food shortages.[19]

Trade

Thanks to petroleum exports, Venezuela usually posts a trade surplus. In recent years, nontraditional (i.e., nonpetroleum) exports have been growing rapidly but still constitute only about a quarter of total exports. The United States is Venezuela's leading trade partner. During 2002, the United States exported $4.4 billion in goods to Venezuela, making it the 25th-largest market for the U.S. Including petroleum products, Venezuela exported $15.1 billion in goods to the U.S., making it its 14th-largest source of goods. Venezuela opposes the proposed Free Trade Agreement of the Americas.

Since 1998 People's Republic of China-Venezuela relations have seen an increasing partnership between the government of the Venezuelan president Hugo Chávez and the People's Republic of China. Sino-Venezuelan trade was less than $500m per year before 1999, and reached $7.5bn in 2009, making China Venezuela's second-largest trade partner,[83] and Venezuela China's biggest investment destination in Latin America. Various bilateral deals have seen China invest billions in Venezuela, and Venezuela increase exports of oil and other resources to China.

Labor

Under Chávez, Venezuela has also instituted worker-run "co-management" initiatives in which workers' councils play a key role in the management of a plant or factory. In experimental co-managed enterprises, such as the state-owned Alcasa factory, workers develop budgets and elect both managers and departmental delegates who work together with company executives on technical issues related to production.[84]

In November 2010, following the expropriation of U.S. bottle-maker Owens-Illinois, workers spent a week protesting outside factories in Valera and Valencia.[85]

Infrastructure

In the 20th century when Venezuela benefitted from oil sales, infrastructure flourished in Venezuela.[32] However, in recent years, Venezuela's public services and infrastructure has suffered; especially utilities such as electricity and water.[32][86]

Transportation

Venezuela has an extensive road system that was initially created in the 1960s helped aid the oil and aluminum industries.[32] The capital Caracas had a modern subway system designed by the French that was finished in 1995, with the subway tunneling more than over 31.6 mi (51 km).[32]

In 1870, Antonio Guzmán Blanco helped create Venezuela's railway system.[32]

The Chavez government launched a National Railway Development Plan designed to create 15 railway lines across the country, with 8,500 miles (13,700 km) of track by 2030. The network is being built in cooperation with China Railways, which is also cooperating with Venezuela to create factories for tracks, railway cars and eventually locomotives. However, Venezuela's rail project is being put on hold due to Venezuela not being able to pay the $7.5 billion and owing China Railway nearly $500 million.[87]

Energy

Venezuela's electrical grid is plagued with occasional blackouts in various districts of the country. In 2011, it had so many problems that rations on electricity were put in place to help ease blackouts.[86] On September 3, 2013, 70% of the country plunged into darkness with 14 of 23 states of Venezuela stating they did not have electricity for most of the day.[88] Another power outage on December 2, 2013 left most of Venezuela in the dark again and happened just days before elections.[89]

Statistics

Economy Data

The Macroeconomic Stabilization Fund (FIEM) decreased from US$2.59 billion in January 2003 to US$700 million in October, but central bank-held international reserves actually increased from US$11.31 billion in January to US$19.67 billion in October 2003.From 2004 to the first half of 2006, non-petroleum On the black market the bolívar fell 28% in 2007 to Bs. 4,750 per US$,[90] and declined to around VEF 5.5 (Bs 5500) per US$ in early 2009.[91]

The economy recovered and grew by 16.8% in 2004. This growth occurred across a wide range of sectors - the oil industry directly provides only a small percentage of employment in the country. International reserves grew to US$27 billion (old data, probably circa 2004). Polling firm Datanalysis noted that real income in the poorest sectors of society grew by 33% in 2004.

On 7 March 2007 the government announced that the Venezuelan bolívar would be redenominated at a ratio of 1 to 1000 at the beginning of 2008 and renamed the bolívar fuerte ("strong bolivar"), to ease accounting and transactions. This was carried out on 1 January 2008, at which time the exchange rate was 2.15 bolívar fuerte per US$.[92] The ISO 4217 code for the bolívar fuerte is "VEF".

Government spending as a percentage of GDP in Venezuela in 2007 was 30%, smaller than other capitalist mixed-economies such as France (49%) and Sweden (52%).[93] According to official sources from the United Nations, the percentage of people below the national poverty line has decreased during the presidency of Hugo Chávez, from 48.1% in 2002 to 28% in 2008.[94][95]

With the 2007 rise in oil prices and rising government expenditures, Venezuela's economy grew by 9% in 2007. Oil prices fell starting in July 2008 resulting in a major loss of income. Hit by a global recession, the economy contracted by 2% in the second quarter of 2009,[96] contracting a further 4.5% in the third quarter of 2009. Chavez's response has been that these standards mis-state economic fact and that the economy should be measured by socialistic standards.[97] For 17 November 2009 the Central Bank reported that private sector activity declined by 4.5% and that inflation was averaging 26.7%. Compounding such problems is a drought which the government says was caused by El Nino, resulting in rationing of water and electricity and a short supply of food.[98]

The year 2010 promises a Venezuela still in recession as Gross Domestic Product has fallen by 5.8% in the first quarter of 2010.[99] The Central Bank has stated that the recession is due largely "to restricted access to foreign currency for imports, lower internal demand and electricity rationing." The oil sector's performance is also particularly troubling, with oil GDP shrinking by 5%. More importantly the Central Bank hints at the root cause of the oil contraction: "the bank said it was due to falls in production, "operative problems", maintenance stoppages and the channeling of diesel to run thermal generators during a power crisis."[99] While the public sector of the economy has fallen 2.8%, the private sector has dropped off 6%.[99]

The year 2013 proved to be difficult for Venezuela as shortages of necessities and extreme inflation attacked the nation's economy. Items became so scarce that nearly one quarter of items were not in stock.[100] The bolívar was devalued to 6.3 per USD in early 2013 taking one third of its value away.[101] However, inflation still continued to rise drastically in the country to the point President Maduro forced stores to sell their items just days before elections. Maduro said that the stores were charging unreasonable prices even though the owners were only charging so much due to the actual devaluation of the bolivar.[102]

As the year 2014 began, it was pretty rough as well. The central bank of Venezuela stopped releasing statistics for the first time in its history as a way to possibly manipulate the image of economy.[103] Venezuela has also dismantled CADIVI, a government body in charge of currency exchange.[62]

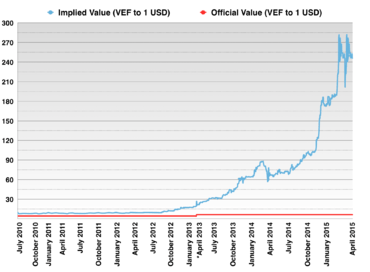

Currency Black Market

*March/April 2013 data is missing

Sources: Banco Central de Venezuela, Dolar Paralelo, Federal Reserve Bank, International Monetary Fund.

The implied value or "black market value" is what Venezuelans believe the Bolivar Fuerte is worth compared to the United States dollar.[104] In the first few years of Chavez's office, his newly created social programs required large payments in order to make the desired changes. On February 5, 2003, the government created CADIVI, a currency control board charged with handling foreign exchange procedures. Its creation was to control capital flight by placing limits on individuals and only offering them so much of a foreign currency.[105] This limit to foreign currency led to a creation of a currency black market economy since Venezuelan merchants rely on foreign goods that require payments with reliable foreign currencies. As Venezuela printed more money for their social programs, the bolívar continued to devalue for Venezuelan citizens and merchants since the government held the majority of the more reliable currencies.[106]

As of January 2014, the official exchange rate is 1 USD to 6.3 VEF while the black market exchange rate is over ten times higher since the actual value of the bolívar is overvalued for Venezuelan businesses. Since merchants can only receive so much necessary foreign currency from the government, they must resort to the black market which in turn raises the merchant's prices on consumers.[107] The high rates in the black market make it difficult for businesses to purchase necessary goods since the government often forces these businesses to make price cuts. This leads to businesses selling their goods and making a low profit, such as Venezuelan McDonald's franchises offering a Big Mac meal for only $1.[108] Since businesses make low profits, this leads to shortages since they are unable to import the goods that Venezuela is reliant on. Venezuela's largest food producing company, Empresas Polar, has stated that they may need to suspend some production for nearly the entire year of 2014 since they owe foreign suppliers $463 million.[109] The last report of shortages in Venezuela showed that 22.4% of necessary goods are not in stock.[110] This was the last report by the government since the central bank no longer posts the scarcity index. This has led to speculation that the government is hiding its inability to control the economy which may create doubt about future economic data released.[111]

Socioeconomic indicators

Like most Latin American countries, Venezuela has an unequal distribution of wealth. The rich tend to be very rich and the poor very poor. In 1970, the poorest fifth of the population had 3% of national income, while the wealthiest fifth had 54%.[112] For comparison the UK 1973 figures were 6.3% and 38.8%, and the US in 1972, 4.5% and 42.8%.[112]

The more recent income distribution data available is for distribution per capita, not per household. The two are not strictly comparable because poor households tend to have more members than rich households; thus, the per household data tends to show less inequality than the per capita data. The table below shows the available per capita data for recent years from the World bank.

| Personal Income Distribution | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Share of personal income (%) received by: | GINI index | |||||

| Poorest fifth | 2nd fifth | 3rd fifth | 4th fifth | Wealthiest fifth | Wealthiest 10% | ||

| 1987 | 4.7 | 9.2 | 14.0 | 21.5 | 50.6 | 34.2 | ~43.42 |

| 1995 | 4.3 | 8.8 | 13.8 | 21.3 | 51.8 | 35.6 | 46.8 |

| 1996 | 3.7 | 8.4 | 13.6 | 21.2 | 53.1 | 37.0 | 48.8 |

| 2000 | 4.7 | 9.4 | 14.5 | 22.1 | 45.4 | 29.9 | 42.0 |

| 2004 | 3.5 | — | 12.9 | — | 54.8 | — | 45.59 |

| 2007 | 5.1 | — | 14.2 | — | 47.7 | — | 42.37 |

| 2010 | 5.7 | — | 14.9 | — | 44.8 | — | 38.98 |

| 2011 | 5.7 | — | 15.9 | — | 44.8 | — | 39.02 |

|

Note that personal (per capita) income distribution, given in this table, is not exactly comparable with household income distribution, given in the previous table, because poor households tend to have more members.

All of the above publications are by the World Bank. | |||||||

Poverty in Venezuela increased during the 1980s and early 1990s, but decreased greatly in the mid to late 1990s. The decreasing trend continued through the Chávez presidency, with the exception of the troubled years 2002 and 2003. The table below shows the percentage of people, and the percentage of households, whose income is below a poverty line which is equal to the price of a market basket of necessities such as food.[114] Note that as an income-based measure of poverty, this omits the effect of some other factors that may affect economic wellbeing, such as the availability of free health care and education.

| Percentage of people and households with income below national poverty line | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | 1989 | ↛ | 1997 | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 | 2003 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 |

| Households | – | ↛ | 48.1 | 43.9 | 42.0 | 40.4 | 39.0 | 48.6 | 55.1 | 47.0 | 37.9 | 30.6 | 28.5 | 27.5 | 26.7 | 26.9 | 26.5 | 21.1 | 27.3 |

| People | 31.3 | ↛ | 54.5 | 50.4 | 48.7 | 46.3 | 45.4 | 55.4 | 62.1 | 53.9 | 43.7 | 36.3 | 33.6 | 32.6 | 31.8 | 32.5 | 31.6 | 25.4 | 32.1 |

| |||||||||||||||||||

| indicator | % |

|---|---|

| Real GDP growth | 1.6 |

| Inflation | 56.2 |

| Gross national saving: (% of GDP) | 23.8 |

| Leading markets 2013 | % of total | Leading suppliers | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 39.1 | United States | 31.7 |

| China | 14.3 | China | 16.8 |

| India | 12.0 | Brazil | 9.1 |

| Netherlands Antilles | 7.8 | Colombia | 4.8 |

| Major exports | % of total | Major imports | % of total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oil & gas | 90.4 | Raw materials and intermediate goods | 44.5 |

| Other | 9.6 | Consumer goods | 24.5 |

| Capital goods | 31.0 | ||

Miscellaneous data

Electricity – production by source:

fossil fuel:

35.7% (2012 est.)

"hydroelectric"

64.3 (2012 est.)

nuclear:

0% (2012 est.)

other:

0% (2012 est.)

Electricity production 127.6 billion kWh (2012 est.)

Electricity – consumption: 85.05 billion kWh (2011 est.)

Electricity – exports: 633 million kWh (2009 est.)

Electricity – imports: 260 million kWh (2009 est.)

Electricity - installed generating capacity: 27.5 million kW (2012 est.)

Agriculture – products: maize, sorghum, sugar cane, rice, bananas, vegetables, coffee; beef, pork, milk, eggs; fish

Currency: 1 bolívar fuerte (Bs. F.) = 100 centimos (Currency code: VEF)

Exchange rates:

bolívares fuertes (Bs. F) per US$1: 6,30 (February 2013), 4,30 (May 2012)

bolívares (Bs) per US$1: 2150 (January 2006), 1440 (September 2002), 652,33 (January 2000), 605,71 (1999), 547,55 (1998), 488,63 (1997), 417,33 (1996), 176,84 (1995)

Social development

In recent years, the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, under the direction of President Hugo Chávez, has made improvements in the realm of social development. With social programs such as the Bolivarian Missions, Venezuela has made progress in areas such as health, education, and poverty. Through what President Hugo Chávez terms 21st Century Socialism,[118] Many of the social policy pursued by Chávez and his administration were jumpstarted by the Millennium Development Goals, eight goals that Venezuela and 188 other nations agreed to in September 2000.[119] According to the United Nations Development Programme, Venezuela was still categorized as having high human development on its Human Development Index in 2013, although human development had declined in Venezuela with the country dropping 10 ranks in one year.[120]

When the international community agreed to the Millennium Development Goals, each country pledged to use social policy to achieve each of the eight goals. The former President of the General Assembly of the United Nations, Ali Abdessalam Treki, stated: “What Venezuela has achieved with regards to the Millennium Development Goals should serve as a model for all other countries."[121]

The country has allocated much of its government spending on social policy. From 1999-2009, 60% of government revenues focused on social programs.[122] Social investment went from 8.4% of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) in 1988 to 18.8% in 2008.[123]

Millennium Development Goals

In 2000, the United Nations adopted the Millennium Development Goals, eight goals that combat social problems in our world today.[124] The eight goals are as follows: eradicate extreme poverty and hunger, achieve universal primary education, promote gender equality and empower women, reduce child mortality, improve maternal health, combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases, ensure environmental sustainability, and develop a global partnership for development. At the September 2010 United Nations Summit, Jorge Valero, Vice-Minister of Foreign Affairs stated: “Venezuela has achieved the majority of the Millennium Development Goals.”[122]

Goal 1: Eradicate extreme poverty and hunger

- Target 1A: Halve the proportion of people living on less than $1 a day

- Target 1B: Achieve decent employment for women, men, and young people

- Target 1C: Halve the proportion of people who suffer from hunger

According to Venezuela government statistics, the percentage of people living in extreme poverty was 29.8% in 2003 and decreased to 12.5% in 2006, the year Venezuela officially met the first target of this goal.[125] The percentage of those living in extreme poverty continued declining and in 2011 was 6.8%.[126] The overall poverty index was 49% in 1998 and lowered to 24.2% in 2009.[127] In terms of unemployment, Venezuela has been able to lower the rate to 7.5% in 2009 in spite of the global financial crisis.[122] However in 2013 during Venezuela's own financial crisis, Venezuela's poverty rate increased to 28.35% with extreme poverty rates increasing 44% to 10.3% according to the Venezuelan government's INE.[128] Estimates of poverty by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC) and Luis Pedro España, a sociologist at the Universidad Católica Andrés Bello, show an increase of poverty in Venezuela.[129] ECLAC showed a 2013 poverty rate of 32% while Pedro España calculated a 2015 rate of 48% with a poverty rate of 70% possible by the end of 2015.[129] According to Venezuelan NGO PROVEA, by the end of 2015, there would be the same number of Venezuelans living in poverty as there was in 2000, reversing the advancements against poverty by Hugo Chávez.[129]

In relation to hunger, under-nutrition was lowered drastically from its 1998-2000 level of 21% to its 2005-2007 level of 6%.[122] Between 1998 and 2010, Venezuela’s food production increased by 44%.[126] In 1991, the population that was undernourished was 10% and decreased to 7% in 2007.[130] The percentage of children under the age of five who are moderately or severely underweight decreased from 6.7% in 1990 to 3.7% in 2007.[130] Infant malnutrition in children below five years of age decreased from 7.7% in 1990 to 2.9% in 2011.[131]

Goal 2: Achieve universal primary education

- Target 2A: By 2015, all children can complete a full course of primary schooling, girls and boys

The total net enrollment ratio in primary education for both sexes increased from 87% in 1999 to 93.9% in 2009.[130] The primary completion rate for both sexes reached 95.1% in 2009, as compared to 80.8% in 1991.[130] In 2005, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization declared Venezuela free of illiteracy.[126] The literacy rates of 15-24 year olds in 2007, for men and women, were 98% and 98.8%, respectively.[130] The free government program, Misión Robinson, is largely responsible for Venezuela's success with literacy rates. Since starting in 2003, the program has taught more than 2.3 million people to read and write. The program has also focused much of its attention on reaching out to geographically isolated and historically excluded members of the population, including indigenous groups and Afro-descendents.[132] According to the Venezuelan government, improvements in primary education and literacy are on target to achieve this goal by the year 2015.[125]

Goal 3: Promote gender equality and empower women

- Target 3A: Eliminate gender disparity in primary and secondary education preferably by 2005, and at all levels by 2015

Gender equality in the education sector has already been achieved, with a ratio of 103 girls for every 100 boys registered in schools.[125] In university education, women’s participation increased by 1.46% in 2009, and there are now more women enrolled in universities than men.[126] Elias Eljuri, President of Venezuela’s National Institute of Statistics, stated that Venezuela ranks second after Cuba in university enrollment.[131]

In the working sector, the percentage of women in the non-agricultural workforce has increased from 35.44% in 1994 to 41.96% in 2009.[122] The percentage of seats held by women in the national parliament has increased to 17% in 2011 from 10% in 1990.[130] At the time of the September 2010 UN Summit, four of Venezuela’s five branches of government were led by women (the legislature, judiciary, electoral authority, and citizen’s branch).[122]

In October 2014, the UN Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women stated that despite the claims made for reform in the 1999 Venezuelan Constitution, there are still "very clear discriminatory laws" against women within Venezuela, with the Venezuelan Supreme Court replying to the stated laws as "antiquated rules".[133]

Goal 4: Reduce child mortality

- Target 4A: Reduce by two-thirds, between 1990 and 2015, the under-five mortality rate

In 2008, the children under-five mortality rate was 16.35 per every 1,000 births, a 49% decrease from 1990.[122] The infant mortality rate decreased from 28 per 1,000 live births in 1990 to 16 per 1,000 live births in 2010,[130] though it increased to 19.33 deaths per 1,000 births in 2014.[134]

The percentage of one year olds immunized against measles has varied between highs of 98% in 2001 and 92% in 1998, from 61% in 1990 and 1992 and a low of 47% in 1995. In 2011, the last year with results available, the rate was 86%.[130]

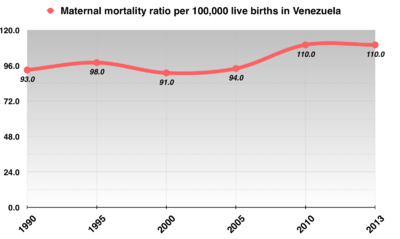

Goal 5: Improve maternal health

Source: United Nations

- Target 5A: Reduce by three quarters, between 1990 and 2015, the maternal mortality ratio

- Target 5B: Achieve, by 2015, universal access to reproductive health

The Venezuelan government has increased the total expenditure on health as a percentage of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the years. In 1996, the level was 3.5% and rose to 6.0% in 2009.[135]

5A - In 2010, the World Bank reported that the maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births was 92, essentially unchanged since 2000 when it was 91, but down from 94 in 1990.[136] However, the United Nations reported an increase in the maternal mortality ratio, which increased from 93 per 100,000 in 1990 to 110 per 100,000 in 2013.[137]

5B - The current contraceptive use among married women 15–49 years old increased from 58% in 1993 to 70.3% in 1998.[130] The Venezuelan government said it has implemented policies and programs aimed at accomplishing on this goal: Proyecto Madre, Misión Barrio Adentro, Misión Niño Jesús, and the National Sexual and Reproductive Health Program.[125] Misión Niño Jesús (Mission Baby Jesus in English) aims to provide better attention to pregnant women. The program attempts to improve hospital infrastructure, increase the availability of medicine, provide health education for pregnant women and young children, and construct prenatal care houses.[138] In 2014 following shortages of many medical and common goods, Venezuelan women have had difficulties accessing contraceptives and were forced to change prescriptions or search several stores and the Internet for their medications.[139]

Goal 6: Combat HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases

- Target 6A: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the spread of HIV/AIDS

- Target 6B: Achieve, by 2010, universal access to treatment for HIV/AIDS for all those who need it

- Target 6C: Have halted by 2015 and begun to reverse the incidence of malaria and other major diseases

6A/6B - The number of primary health care physicians treating HIV/AIDS and other diseases has increased from 1,628 in 1998 to 19,500 in 2009.[126] The number of people receiving free antiretroviral therapy increased from 1,059 in 1999 to 25,657 in 2008. Spending on HIV has exceeded US $230 million.[125] As of 2014, shortages of antiretroviral medicines to treat HIV/AIDS affected about 50,000 Venezuelans, potentially causing thousands of Venezuelans with HIV to develop AIDS.[140]

6C - In 2010, the Venezuelan Ministry of Health reported that they were intensifying efforts to reach all sectors of the population in order to reduce the prevalence of diseases such as HIV/AIDS and malaria.[141] The prevalence of tuberculosis per 100,000 people has decreased slightly from 51 in 1990 to 48 in 2010.[135] The tuberculosis treatment success rate has increased from 68% in 1994 to 83% in 2008.[130]

In terms of malaria, during the period lasting from 1995 to 2004, the malaria mortality rate ranged from 0.10-0.36 deaths per 100,000 people. Almost a third of these deaths were children.[142] However, as of August 2014, Venezuela is the only country in Latin America where the incidence of malaria is increasing, allegedly due to illegal mining and in 2013, Venezuela registered the highest number of cases of malaria in the past 50 years, with 300 of 100,000 Venezuelans being infected with the disease. Medical shortages in the country also hampered the treatment of Venezuelans.[143]

Goal 7: Ensure environmental sustainability

- Target 7A: Integrate the principles of sustainable development into country policies and programs; reverse loss of environmental resources

- Target 7B: Reduce biodiversity loss, achieving, by 2010, a significant reduction in the rate of loss

- Target 7C: Halve, by 2015, the proportion of the population without sustainable access to safe drinking water and basic sanitation (for more information see the entry on water supply)

- Target 7D: By 2020, to have achieved a significant improvement in the lives of at least 100 million slum-dwellers

7A/7B - Venezuela has one of the highest biodiversity richness levels in the world. The nation is ranked in the top 10 countries with the highest biodiversity on the planet.[144] Venezuela has some known 2,356 known species of amphibians, birds, mammals, and reptiles. Out of these, 13.3% are endemic, meaning they exist in no other country, and 5.6% are threatened. There are over 21,000 species of plants in the country, and 38.0% of them are endemic.[145]

The Ministry of People’s Power for the Environment received $675 million from the 2012 national budget to develop policies, strategies, plans, and actions aimed at boosting environmental conservation and education.[126] Roughly 73% of Venezuela’s territory is covered with natural areas under protection. The country ranks second behind Ecuador in the amount of protected area.[146] In 2006, President Hugo Chávez launched Misión Arbol, a program that attempts to combat the deforestation of Venezuela.[147] Through this project, 22,000 acres of trees have been planted.[125]

Despite changes made by the Ministry of People’s Power for the Environment, in August 2014, the Venezuelan government merged it into the newly formed Ministry of Housing, Habitat and Eco-socialism, an action criticized by multiple environmental organizations in Venezuela. The Ecological Movement of Venezuela rejected the move saying it "demonstrates the failure of Nicolás Maduro and his Cabinet in environmental management".[148][149] The president of the environmental group Vitalis, Diego Diaz Martin, stated that Venezuela was thrown back 40 years in environmental management due to the ministerial merger calling the move "more ideological than technical or economic".[150][151]

7C - The proportion of people with sustainable access to safe drinking water increased from 68% in 1990 to 92% in 2007, above the target of 84%.[123] The proportion of the population using improved sanitation facilities increased to 91 in 2005 from 82 in 1990.[130]

Goal 8: Develop a global partnership for development

- Target 8A: Develop further an open, rule-based, predictable, non-discriminatory trading and financial system

- Target 8B: Address the special needs of least developed countries, landlocked developing countries and small island developing States

- Target 8C: Deal comprehensively with developing countries' debt

- Target 8D: In cooperation with pharmaceutical companies, provide access to affordable, essential drugs in developing countries

- Target 8E: In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technologies, especially information and communications

8A - In 2014, Venezuela's economic freedom was ranked fourth as one of the least free countries in the 2014 Index of Economic Freedom by the Heritage Foundation and the Wall Street Journal.[152] Venezuela was ranked as an unfree rating since the late 1990s.[153]

8B - The Bolivarian Government of Venezuela has continuously defend Palestine[154][155][156] Israel's interests in Venezuela would be represented by Canada.[157] Venezuela officially recognized the State of Palestine in 2009.[158]

8C - In dealing with debt, Venezuela's debt service as a percentage of exports and net income from abroad has decreased from its 1990 level of 19.6% to 10.5% in 2004.[159] Venezuela's debt has increased

8D - In Venezuela, shortages of several pharmaceutical items were limited due to economic difficulties; including antiretroviral medicines to treat HIV/AIDS[140] and acetaminophen.[160]

8E - In 1990, the number of Internet users was minimal, but by 2010, 35.63% of Venezuelans were Internet users.[130] In fact, the number of Internet subscribers has increased sixfold.[125] Programs such as the National Technological Literacy Plan, which provides free software and computers to schools, have assisted Venezuela in meeting this goal.[161] However, several experts state that the poor infrastructure in Venezuela had created a poor quality of Internet in Venezuela, which has one of the slowest Internet speeds in the world.[162] The lack of US dollars due to the Venezuelan governments currency controls has also damaged Internet services because technological equipment must be imported into Venezuela.[162]

The number of fixed telephone lines per 100 inhabitants was 7.56 in 1990. The number increased to 24.44 in 2010.[130] In 2000, 2,535,966 Venezuelans had landline telephones. By 2009, this had increased to 6,866,626.[122]

The Bolivarian government has also launched an aerospace program in cooperation with the People's Republic of China who built and launched two satellites that are currently in orbit—a communications satellite called Simón Bolívar, and a remote sensing satellite called Miranda. In July 2014 President Maduro announced that a third satellite would be built by Chinese-Venezuelan bilateral cooperation.[163][164]

See also

- Central Bank of Venezuela

- List of Venezuelan companies

- List of Venezuelan cooperatives

Sources

Government of Venezuela, Instituto Nacional de Estadística (National Institute of Statistics.) Wide range of statistics. Adding pobreza/menupobreza.asp to the URL gives a menu of poverty statistics.

United Nations, UNdata Explorer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Venezuela: Economy. CIA World Factbook. 19 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ World Economic Outlook Database, October 2012

- ↑ "Country and region specific forecasts and data". World Bank. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Eclac: Venezuela's GDP at -3% in 2014". El Universal. 3 January 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Venezuela 2014 inflation hits 68.5 pct -central bank". Reuters. 13 February 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- ↑ Boyd, Sebastian (30 December 2014). "Venezuelan 1,000% Inflation Seen by BofA Without Weaker Bolivar". Bloomberg. Retrieved 4 January 2015.

- ↑ "En un año hogares pobres crecieron en 416.326". El Nacional. 24 May 2014. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- ↑ "Desempleo se ubicó en 7,9% en enero, según el INE". La Patilla. 13 March 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Ease of Doing Business in Venezuela, RB". Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Export Partners of Venezuela". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "Import Partners of Venezuela". CIA World Factbook. 2012. Retrieved 2013-07-25.

- ↑ "S&P slashes Venezuela credit rating on oil rout". Reuters. 9 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- ↑ "Rating Action: Moody's downgrades Venezuela's rating to Caa3 from Caa1; outlook stable The document has been translated in other languages". Moody's. Retrieved 13 January 2015.

- ↑ "Fitch Downgrades Venezuela's IDRs to 'CCC'". Reuters. 18 December 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's international reserves total USD 19.81 billion". El Universal. 10 October 2014. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Background Note: Venezuela U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 29 October 2011.

- ↑ (Spanish)"Ingresos Petroleros de Venezuela 1999-2008." Centro de Investigaciones Económicas. 21 June 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ "Crude Oil Supply Vs. OPEC Output Target:Venezuela." IEA Oil Market Report. 11 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 "Venezuela’s currency: The not-so-strong bolívar". The Economist. 11 February 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- ↑ Mander, Benedict (10 February 2013). "Venezuelan devaluation sparks panic". Financial Times. Retrieved 11 February 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela’s economy: Medieval policies". The Economist. 20 August 2011. Retrieved 23 February 2014.

- ↑ (Spanish)"Venezuela es el país de Latinoamérica que tiene la inflación más alta." Noticias 24. 13 May 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Yergin, Daniel. The Prize: The Epic Quest for Oil, Money, and Power. New York:Simon and Schuster. 1990. pp 233-36; 432

- ↑ Yergin 1990, p 435

- ↑ Yergin 1990, pp 510-13

- ↑ Yergin 1990, p 767

- ↑ NationMaster. "GDP per capita in 1950 statics.".

- ↑ Alexander, Robert. "Nature and Progress of Agrarian Reform in Latin America." The Journal of Economic History. Vol. 23, No. 4 (Dec. 1963), pp 559-573.

- ↑ McCaughan, Michael. The Battle of Venezuela. New York: Seven Stories Press. 2005. p 63.

- ↑ McCaughan, Michael. The Battle of Venezuela. London: Latin America Bureau. 2004. p 31.

- ↑ McCaughan 2004, p 32.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 32.7 Heritage, Andrew (December 2002). Financial Times World Desk Reference. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 618–621. ISBN 9780789488053.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 "Venezuela Inflation rate (consumer prices)". Indexmundi. 2010. Retrieved 16 August 2010.

- ↑ Kelly, Janet, and Palma, Pedro (2006), "The Syndrome of Economic Decline and the Quest for Change", in McCoy, Jennifer and Myers, David (eds, 2006), The Unraveling of Representative Democracy in Venezuela, Johns Hopkins University Press. p207

- ↑ McCaughan 2004, p 73.

- ↑ United Nations data, National accounts estimates of main aggregates.

- ↑ Weisbrot and Sandoval, 2008. Sections: 'Executive Summary,' and 'Social Spending, Poverty, and Employment.'

- ↑ UN data site >> World Bank estimates >> GDP deflator, national currency.

- ↑ Grant, Will (15 November 2010). "Why Venezuela's government is taking over apartments". BBC. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ "Expropriations in Venezuela". The Economist. 29 October 2010.

- ↑ Romero, Simon (28 February 2011). "A 45-Story Walkup Beckons the Desperate". New York Times. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- ↑ Mead, Derek. "Inside Caracas' Tower of David, the World's Tallest Slum". Vice. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 43.2 Toothaker, Christopher. "Chavez: Venezuela's economy soon to recover." Bloomberg Businessweek. 8 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Cancel, Daniel. "Chavez Says Venezuela's Economy Is `Already Recovering' Amid Recession." Bloomberg. 8 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ (Spanish)"FMI: Venezuela único país cuya economía se contraerá este año." El Universal. 21 April 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Hanke, John H. "Measuring Misery around the World". The CATO Institute. Retrieved 30 April 2014.

- ↑ "Country Rankings: World & Global Economy Rankings on Economic Freedom". The Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 26 March 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Slashes Currency Value". Wall Street Journal. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Lopez, Virginia (26 September 2013). "Venezuela food shortages: 'No one can explain why a rich country has no food'". The Guardian. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Facing shortages, Venezuela takes over toilet paper factory". CNN. 21 September 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuelan Inflation Hits New Heights". Wall Street Journal. 7 November 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "World Economic outlook April 2013" (PDF). International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Mogollon, Mery; Kraul, Chris (12 November 2013). "Stuck in Venezuela with those currency exchange blues". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Bases, Daniel (14 December 2013). "UPDATE 2-S&P cuts Venezuela debt rating to B-minus". Reuters. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Sanchez, Fabiola (23 April 2014). "Venezuela's Economic Crisis Catches up With Malls". ABC News. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Rating: Venezuela Credit Rating". Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Hanke, Steve. "Venezuela’s Playbook: The Communist Manifesto". CATO Institute. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ "Ford Cutting Production in Venezuela on Growing Dollar Shortage". Businessweek. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ Mogollon, Mery (24 January 2014). "Venezuela sees more airlines suspend ticket sales, demand payment". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (24 January 2014). "Airlines keep cutting off Venezuelans from tickets". USA Today. Retrieved 25 January 2014.

- ↑ Wilson, Peter (10 January 2014). "Venezuelans blocked from buying flights out". USA Today. Retrieved 15 January 2014.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 "Venezuela Shuffles Economic Team". The Wall Street Journal. 15 January 2014. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Hagiwara, Yuki (7 February 2014). "Toyota Halts Venezuela Production as Car Sales Fall". Bloomberg. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ Deniz, Roberto (7 February 2014). "General Motors sees no resolution to operations in Venezuela". El Universal. Retrieved 8 February 2014.

- ↑ "Médicos del Hospital Universitario de Caracas suspenden cirugías por falta de insumos". Globovision. 21 February 2014. Retrieved 21 February 2014.

- ↑ "Latin America’s weakest economies are reaching breaking-point". Economist. 1 February 2014.

- ↑ "Doctors say Venezuela's health care in collapse". Associated Press. Retrieved 22 February 2014.

- ↑ Fernanda Zambrano, María (19 March 2014). "Clínicas del país presentan fallas en 109 productos". Union Radio. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ Chinea, Eyanir (20 March 2014). "Sin dólares para importar medicinas, salud de Venezuela en terapia intensiva". Reuters (Latin America). Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- ↑ "WORLD ECONOMIC OUTLOOK April 2014" (PDF). Report. International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ "IMF Data Mapper". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 9 April 2014.

- ↑ "Coca Cola prevé un impacto desfavorable en sus operaciones en Venezuela". La Patilla. 15 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ "El pollo es comercializado con sobreprecio de 114 a 231%". El Tiempo. 14 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ "La crisis golpea a los servicios de inteligencia de Venezuela Read more here: http://www.elnuevoherald.com/2014/04/13/1724939/la-crisis-golpea-a-los-servicios.html#storylink=cpy". El Nuevo Herald. 13 April 2014. Retrieved 15 April 2014.

- ↑ Deniz, Roberto (4 May 2014). "Banco Central reporta que la escasez de vehículos llega al 100%". El Universal. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "Citi considera que la economía venezolana es un "desastre"". El Universal. 3 May 2014. Retrieved 5 May 2014.

- ↑ "En imágenes: Así fue el último día de General Motors en Venezuela". Venezuela Al Dia. 16 May 2014. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ↑ "Dolorosa imagen de nuestra industria automotriz: El cierre de General Motors Venezolana". La Patilla. Retrieved 19 May 2014.

- ↑ (Spanish) "Contribución petrolera se duplica por ajuste cambiario." El Universal. 11 January 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Blasco, Emili (23 April 2014). "Venezuela se queda sin suficientes divisas para pagar las importaciones". ABC News (Spain). Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela's aluminum industry operates at 29% of capacity". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ "Venezuela's aluminum and steel production below 1997 numbers". Retrieved 15 November 2012.

- ↑ Suggett, James. "Latest Venezuela-China Deals: Orinoco Agriculture, Civil Aviation, Steel, and $5 Billion Credit Line." Venezuelanalysis.com. 3 August 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Bruce, Iain. "Chavez calls for democracy at work." BBC News. 17 August 2005. Retrieved 22 September 2006.

- ↑ Devereux, Charlie (26 October 2010). "Owens-Illinois Seizure by Chavez May Undermine Venezuela's Empresas Polar". Bloomberg.

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Toothaker, Christopher (16 June 2011). "Venezuela's Electricity To Be Rationed Following Recurring Power Outages". Huffington Post. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Han Shih, Toh (11 April 2013). "China Railway Group's project in Venezuela hits snag". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Power cut paralyses Venezuela". The Guardian. 4 September 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ "Venezuela Power Outage Plunges Most Of Nation Into Darkness". Huffington Post. 2 December 2013. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- ↑ Romero, Simon. "Venezuela to Give Currency New Name and Numbers." New York Times. 18 March 2007. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Molano, Walter. "Venezuela is Priced for Failure." Latin American Herald Tribune. 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Ellsworth, Brian. "Venezuela cuts three zeros off bolivar currency." Reuters. 1 January 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Weisbrot, Mark, and Sandoval, Luis.The Venezuelan Economy in the Chávez Years.Center for Economic and Policy Research. July 2007.

- ↑ Forero, Juan. "Despite billions in U.S. aid, Colombia struggles to reduce poverty." Washington Post. 19 April 2010. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ (Spanish) "Situación de la pobreza en la región." Panorama social de América Latina. 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2010.

- ↑ Daniel, Frank. "Venezuela economy shrinks for first time in 5 years." Reuters. 20 August 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Daniel, Frank. "Chavez says Venezuela in recession, by US yardstick." Reuters. 22 November 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ Márquez, Humberto. "El Niño Dries Up Water, Power, Food Supply." IPS News. 23 October 2009. Retrieved 3 September 2010.

- ↑ 99.0 99.1 99.2 Cawthorne, Andrew."Venezuela recession drags, GDP falls 5.8 pct Q1". Reuters. 25 May 2010. Retrieved 13 August 2010

- ↑ "Venezuela’s Forced Price Cuts Damp World’s Fastest Inflation (2)". Businessweek. 30 December 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Slashes Currency Value". The Wall Street Journal. 9 February 2013. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Mogollon, Mery; Kraul, Chris (16 November 2013). "Government-ordered price cuts spawn desperation shopping in Venezuela". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ Kurmanaev, Anatoly (9 January 2014). "Venezuela in Data Denial After Inflation Tops 50%: Andes Credit". Bloomberg. Retrieved 16 January 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela’s black market rate for US dollars just jumped by almost 40%". Quartz. 26 March 2014. Retrieved 27 March 2014.

- ↑ CADIVI, CADIVI, una medidia necesaria

- ↑ Hanke, Steve. "The World's Troubled Currencies". The Market Oracle. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Gupta, Girish (24 January 2014). "The ‘Cheapest’ Country in the World". TIME. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Pons, Corina (14 January 2014). "McDonald’s Agrees to Cut the Price of a Venezuelan Big Mac Combo". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Goodman, Joshua (22 January 2014). "Venezuela overhauls foreign exchange system". Bloomberg. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ Vyas, Kejal (30 December 2013). "Venezuela's Consumer Prices Climbed 56% in 2013". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela inflation data under scrutiny". Buenos Aires Herald. 31 December 2013. Retrieved 26 January 2014.

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 World Bank. "Table 24." World Development Report. 1980. pp 156–157.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 113.3 http://www.ine.gov.ve/documentos/Boletines_Electronicos/Estadisticas_Sociales_y_Ambientales/Sintesis_Estadistica_de_Pobreza_e_Indicadores_de_Desigualdad/pdf/BoletinPobreza.pdf

- ↑ "Ficha Técnicas de Línea de Pobreza por Ingreso." Estadísticas Sociales y Ambientales. El Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. Retrieved 4 September 2010. The Instituto Nacional de Estadística describes their method for compiling these statistics.

- ↑ "Pobreza". instituto nacional de estadistica. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela Achieves Millennium Goals" (PDF). Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. Retrieved 1 September 2014.

- ↑ "Factsheet". The Economist. Retrieved 17 February 2009.

- ↑ Wilpert, Gregory. "The Meaning of 21st Century Socialism for Venezuela." Venezuela Analysis. 11 July 2006. Web. 19 March 2012. <http://venezuelanalysis.com/analysis/1834>.

- ↑ "The Millennium Development Goals Report 2011." United Nations. 2011. Web. 2 April 2012. <http://www.un.org/millenniumgoals/11_MDG%20Report_EN.pdf>.

- ↑ "2014 Human Development Report Summary" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 2014. pp. 21–25. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ↑ Mather, Steven. “UN General Assembly President Praises Venezuela for Development Goals Progress.” Venezuela Analysis. 24 June 2010. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ 122.0 122.1 122.2 122.3 122.4 122.5 122.6 122.7 “Fact Sheet: Millennium Development Goals.” Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. 12 October 2010. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ 123.0 123.1 Janicke, Kiraz. “Venezuela Reaches the Millennium Development Goals.” Venezuela Analysis. 14 July 2009. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ “United Nations Millennium Declaration.” UN General Assembly. 8 September 2000. Web. 4 March 2012.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 125.3 125.4 125.5 125.6 “Venezuela Achieves Millennium Goals.” Ministry of People's Power for Communication and Information. 2010. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 126.2 126.3 126.4 126.5 “Venezuela Leads on UN Human Development Goals.” Australia-Venezuela Solidarity Network. 21 November 2011. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ "Press Conference by Venezuela on Millennium Development Goals." UN News Center. 21 September 2010. Web 19 March 2012.

- ↑ "Pobreza". INE. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 129.2 Gallagher, J. J. (25 March 2015). "Venezuela: Does an increase in poverty signal threat to government?". The Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 130.3 130.4 130.5 130.6 130.7 130.8 130.9 130.10 130.11 130.12 “Millennium Development Goals Indicators.” United Nations Statistics Division. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 President of the National Institute of Statistics, Elias Eljuri “Venezuela has a universal and inclusive social policy” Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela. 4 February 2012. Web 4 March 2012.

- ↑ Ellis, Edward. "Venezuela Celebrates Five Years Free of Illiteracy." Venezuela Analysis. 7 November 2010. Web. 20 March 2012.

- ↑ "ONU denuncia que en Venezuela persisten leyes que discriminan a las mujeres". La Patilla. 21 October 2014. Retrieved 22 October 2014.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- ↑ 135.0 135.1 "Global Health Observatory Data Repository." World Heath Organization. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Maternal Mortality Ratio." The World Bank. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Maternal mortality ratio per 100,000 live births". Millennium Development Goals Indicators. United Nations.

- ↑ Pearson, Tamara. "New Venezuelan Mission Aims to Lower Maternal and Infant Mortality Rates." Venezuela Analysis. 23 December 2009. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Higuerey, Edgar (5 September 2014). "Escasez de anticonceptivos hace cambiar tratamientos". El Tiempo. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ 140.0 140.1 "Venezuela Faces Health Crisis Amid Shortage of HIV/Aids Medication". Fox News Latino. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ Pearson, Tamara. "Chávez Introduces New Venezuelan Health Minister and New Maternity Facilities." Venezuela Analysis. 23 May 2010. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Rodriguez-Morales, Alfonso; Benitez, J. A.; Arria, M. (2007). "Malaria Mortality in Venezuela". Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 54 (2): 94–101. doi:10.1093/tropej/fmm074. PMID 17906318.

- ↑ Pardo, Daniel (23 August 2014). "The malaria mines of Venezuela". BBC. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑ "Country Profile - Venezuela." Convention on Biological Diversity. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Venezuela." Mongabay. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Environment Statistics." Nation Master. Web 1 April 2012.

- ↑ Fox, Michael. "Misión Arbol: Reforesting Venezuela." Venezuela Analysis. 23 June 2006. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ "Movimiento ecológico: Sacudón sólo afectó al ambiente y al quinto motor". El Tiempo. 3 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "Movimiento Ecológico rechazó eliminación del Ministerio de Ambiente". El Universal. 5 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela retrocede 40 años en materia ambiental con fusión ministerial". El Universal. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "Ambientalistas: Venezuela retrocede 40 años en la materia con fusión ministerial". El Nacional. 4 September 2014. Retrieved 7 September 2014.

- ↑ "Venezuela". Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "Graph The Data". Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 20 October 2014.

- ↑ "World reacts to the conflict in Gaza". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- ↑ Venezuela's Support for Palestine A Model for Third World Democracy

- ↑ Associated Press, Haaretz, 16 September 2009, Venezuela: Spain will represent our interests in Israel

- ↑ Canada-Israel Committee, 5 August 2009, Canada to Help Israel with Visas in Venezuela

- ↑ Venezuelanalysis.com, 30 April 2009, Venezuela and the Palestinian Authority Establish Diplomatic Relations

- ↑ "Millennium Development Goals: Goal 8." Index Mundi. Web 2 April 2012.

- ↑ Forero, Juan (22 September 2014). "Venezuela Seeks to Quell Fears of Disease Outbreak". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 24 September 2014.

- ↑ "Fact Sheet: Venezuela and the Millennium Development Goals." Embassy of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela to the UK and Ireland. Web. 20 March 2012.

- ↑ 162.0 162.1 Pardo, Daniel (22 September 2014). "¿Por qué internet en Venezuela es tan lento?". BBC. Retrieved 25 September 2014.

- ↑ 21 July 2014. "En 7 claves - Los acuerdos China-Venezuela firmados este lunes". Últimas Noticias. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

The agreement, signed for the development of the program satellite VRSS2, provides for the two nations to share knowledge about the manufacture of the new remote sensing satellite, which will serve to strengthen mapping capabilities in the country, and to contribute to the development of the Venezuelan aerospace industry.

- ↑ Magan, Veronica (23 August 2013). "Venezuela: Latin America’s Next Space Pioneer?". Satellite Today. Retrieved 28 September 2014.

External links

- Venezuela Energy Profile from the Energy Information Administration

- Venezuela to Give Currency New Name and Numbers

- Banco Central de Venezuela

- Venezuela's Economy During the Chavez Years

- Venezuela Nationalizes Gas Plant and Steel Companies, Pledges Worker Control by James Suggett, 22 May 2009

- Venezuela's Economic Recovery: Is It Sustainable? - Center for Economic and Policy Research report, September 2012

- Map of Venezuela's economic and transportation network

- Tariffs applied by Venezuela as provided by ITC's Market Access Map, an online database of customs tariffs and market requirements.

- International Trade Statistics - Venezuela

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||