Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union

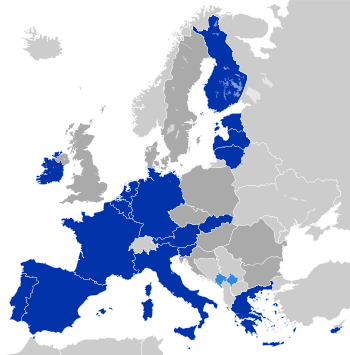

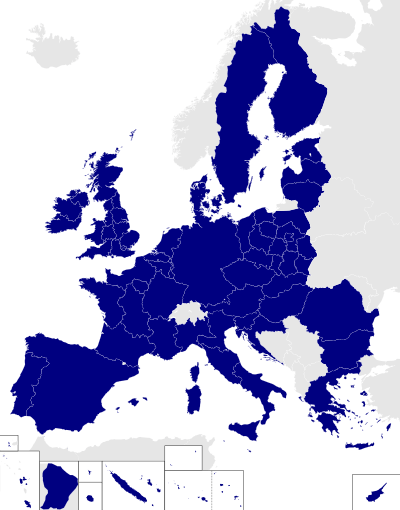

The Economic and Monetary Union (EMU)[1][2] is an umbrella term for the group of policies aimed at converging the economies of all member states of the European Union at three stages. Both the 19 eurozone states and the 9 non-euro states are EMU members. A Member State however needs to comply and be a part of the "third EMU stage", before being able to adopt the euro currency; and as such the "third EMU stage" has also become largely synonymous with the eurozone.

All Member States of the European Union, except Denmark and the United Kingdom, have committed themselves by treaty to join the "third EMU stage". The Copenhagen criteria is the current set of conditions of entry for new states wanting to join the EU. It contains the requirements that need to be fulfilled and the time framework within which this must be done, in order for a country to join the monetary union. An important element of this, is a participation for minimum two years in the European Exchange Rate Mechanism ("ERM II"), in which candidate currencies demonstrate economic convergence by maintaining limited deviation from their target rate against the euro.

Nineteen member states of the European Union, including most recently Lithuania, have entered the "third EMU stage" and have adopted the euro as their currency. Denmark participate in the Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM II). Denmark and United Kingdom has received a special opt out from the EU Treaties, allowing for a permanent membership of ERM II, without being required to enter into the "third EMU stage". In regards of the remaining non-euro member states (Sweden, Poland, Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Bulgaria and Croatia), they are committed by treaty to enter the third stage upon the time of complying with all convergence criteria; of which the last one (ERM II membership) however is something the member state can choose not to apply for, if they do not want to adopt the euro. The non-euro EU member states will continue to use their own local and historic currencies.

History

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

Elections

|

First ideas of an economic and monetary union in Europe were raised well before establishing the European Communities. For example, already in the League of Nations, Gustav Stresemann asked in 1929 for a European currency[3] against the background of an increased economic division due to a number of new nation states in Europe after World War I.

A first attempt to create an economic and monetary union between the members of the European Communities goes back to an initiative by the European Commission in 1969, which set out the need for "greater co-ordination of economic policies and monetary cooperation,"[4] which was followed by the decision of the Heads of State or Government at their summit meeting in The Hague in 1969 to draw up a plan by stages with a view to creating an economic and monetary union by the end of the 1970s.

On the basis of various previous proposals, an expert group chaired by Luxembourg’s Prime Minister and Finance Minister, Pierre Werner, presented in October 1970 the first commonly agreed blueprint to create an economic and monetary union in three stages (Werner plan). The project experienced serious setbacks from the crises arising from the non-convertibility of the US dollar into gold in August 1971 (i.e., the collapse of the Bretton Woods System) and from rising oil prices in 1972. An attempt to limit the fluctations of European currencies, using a snake in the tunnel, failed.

The debate on EMU was fully re-launched at the Hannover Summit in June 1988, when an ad hoc committee (Delors Committee) of the central bank governors of the twelve member states, chaired by the President of the European Commission, Jacques Delors, was asked to propose a new timetable with clear, practical and realistic steps for creating an economic and monetary union.[5] This way of working was derived from the Spaak method.

The Delors report of 1989 set out a plan to introduce the EMU in three stages and it included the creation of institutions like the European System of Central Banks (ESCB), which would become responsible for formulating and implementing monetary policy.[6]

The three stages for the implementation of the EMU were the following:

Stage One: 1 July 1990 to 31 December 1993

- On 1 July 1990, exchange controls are abolished, thus capital movements are completely liberalised in the European Economic Community.

- The Treaty of Maastricht in 1992 establishes the completion of the EMU as a formal objective and sets a number of economic convergence criteria, concerning the inflation rate, public finances, interest rates and exchange rate stability.

- The treaty enters into force on the 1 November 1993.

Stage Two: 1 January 1994 to 31 December 1998

- The European Monetary Institute is established as the forerunner of the European Central Bank, with the task of strengthening monetary cooperation between the member states and their national banks, as well as supervising ECU banknotes.

- On 16 December 1995, details such as the name of the new currency (the euro) as well as the duration of the transition periods are decided.

- On 16–17 June 1997, the European Council decides at Amsterdam to adopt the Stability and Growth Pact, designed to ensure budgetary discipline after creation of the euro, and a new exchange rate mechanism (ERM II) is set up to provide stability above the euro and the national currencies of countries that haven't yet entered the eurozone.

- On 3 May 1998, at the European Council in Brussels, the 11 initial countries that will participate in the third stage from 1 January 1999 are selected.

- On 1 June 1998, the European Central Bank (ECB) is created, and in 31 December 1998, the conversion rates between the 11 participating national currencies and the euro are established.

Stage Three: 1 January 1999 and continuing

- From the start of 1999, the euro is now a real currency, and a single monetary policy is introduced under the authority of the ECB. A three-year transition period begins before the introduction of actual euro notes and coins, but legally the national currencies have already ceased to exist.

- On 1 January 2001, Greece joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2002, the euro notes and coins are introduced.

- On 1 January 2007, Slovenia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2008, Cyprus and Malta join the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2009, Slovakia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2011, Estonia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2014, Latvia joins the third stage of the EMU.

- On 1 January 2015, Lithuania joins the third stage of the EMU.

Criticism

There have been debates as to whether the Eurozone countries constitute an optimum currency area.[7]

There has also been a lot of doubt if all eurozone states really fulfilled a "high degree of sustainable convergence" as demanded by the Maastricht treaty as condition to join the Euro without getting into financial trouble later on.

Monetary policy inflexibility

Since membership of the eurozone establishes a single monetary policy for the respective states, they can no longer use an isolated monetary policy, e.g. to increase their competitiveness at the cost of other eurozone members by printing money and devalue, or to print money to finance excessive government deficits or pay interest on unsustainable high government debt levels. As a consequence, if member states do not manage their economy in a way that they can show a fiscal discipline (as they were obliged by the Maastricht treaty), they will sooner or later risk a sovereign debt crisis in their country without the possibility to print money as an easy way out. This is what happened to Greece, Ireland, Portugal, Cyprus, and Spain.[8]

Plans for a Genuine Economic and Monetary Union

Being of the opinion that the pure austerity course was not able to solve the Euro-crisis, French President François Hollande reopened the debate about a reform of the architecture of the Eurozone. The intensification of work on plans to complete the existing EMU in order to correct its economic errors and social upheavals soon introduced the keyword "genuine" EMU.[9] However, a correction of the defective Maastricht currency architecture with the introduction of a fiscal capacity of the EU, common debt management and a completely integrated banking union appears to be no prospect of that at present.[10] Additionally, there is a widespread fear that a process of strengthening the Union's power to intervene in Euro Area member states and to impose flexible labour markets and flexible wages might constitute a serious threat to Social Europe.[11]

References

- ↑ EMU is sometimes incorrectly referenced as the "European Monetary Union". The official and correct name is "Economic and Monetary Union", of which both the 18 eurozone states and the 10 non-euro states are members.

- ↑ ECB webpage on Economic and Monetary Union

- ↑ Link

- ↑ Barre Report

- ↑ Verdun A., The role of the Delors Committee in the creation of EMU: an epistemic community?, Journal of European Public Policy, Volume 6, Number 2, 1 June 1999 , pp. 308–328(21)

- ↑ Delors Report

- ↑ "As Euro Nears 10, Cracks Emerge in Fiscal Union" (New York Times, 1 May 2008)

- ↑ "Project Syndicate-Martin Feldstein-The French Don't Get It-December 2011". Project-syndicate.org. 2011-12-28. Retrieved 2012-05-14.

- ↑ Hacker, Björn (2013): On the Way to a Fiscal or a Stability Union? The Plans for a »Genuine« Economic and Monetary Union, FES, online at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/10400.pdf

- ↑ Busch, Klaus (2012): Is the Euro Failing? Structural Problems and Policy Failures Bringing Europe to the Brink, FES, online at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/09034.pdf

- ↑ Janssen, Ronald (2013): A Social Dimension For A Genuine Economic Union, SEJ, online at: http://www.social-europe.eu/2013/03/a-social-dimension-for-a-genuine-economic-union/

Further reading

- Simonazzi, A. and Vianello, F. [1998], “Italy towards European Monetary Union (and domestic socio-economic disunion)”, in: B.H. Moss, J. Michie (eds.), The Single European Currency in National Perspective. A community in Crisis?, Macmillan, London, ISBN 978-03-33-79293-3.

- Hacker, Björn (2013): On the Way to a Fiscal or a Stability Union? The Plans for a »Genuine« Economic and Monetary Union, FES, online at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/id/ipa/10400.pdf

External links

- EMU: A Historical Documentation (European Commission)

- The euro (European Commission Economic and Financial Affairs)

- Central Bank Rates: ECB Key Rate, chart and data

- European integration process: 1969-1979 Crises and revival: Economic and Monetary Union cooperation subject file by the CVCE (Centre of European Studies)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||