Eastern Front (1941)

| Eastern Front (1941) | |

|---|---|

_cover.jpg) | |

| Developer(s) | Chris Crawford |

| Publisher(s) | APX, Atari, Inc. |

| Platform(s) | Atari 8-bit |

| Release date(s) | 1981 |

| Genre(s) | Turn-based strategy |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

| Distribution | Cassette, floppy disk, cartridge |

Eastern Front (1941) is a computer wargame for the Atari 8-bit series created by Chris Crawford in 1981. Recreating the German invasion of Russia during World War II, Eastern Front covers the historical area of operations during the 1941–1942 period. The player commands German units at the corps level and must contend with the computer-controlled Russians, as well as terrain, weather, supplies, unit morale, and fatigue. Eastern Front was widely lauded in the press.

Gameplay

- Unless otherwise noted, this section refers to the original game manual, available here.

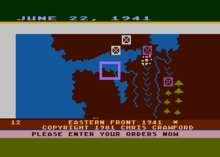

Eastern Front puts the user in control of the Germans, in white, while the computer plays the Russians, in red. Units are represented as boxes for armored corps or cavalry, and crosses for infantry, an attempt to replicate conventional military symbols given the low resolution.

The screen shows only 1/9 of the entire map at one time, smooth-scrolling around it when the joystick-controlled cursor reaches the edges of the screen.[1] According to creator Chris Crawford, it is the first wargame to feature a smooth-scrolling map.[2][3] The map covers the area from just north of Leningrad at the top to Sevastopol at the bottom, and from Warsaw on the left to just east of Stalingrad on the right. The terrain is varied, including flatland, forests, mountains, rivers and swamps, each with their own effects on movement. Cities are displayed in white, and are a major source of "victory points", the player's score.

The game is modal, switching between an order entry mode and a combat mode. During order entry the joystick is used to select units and enter movement in the four cardinal directions. Up to eight orders can be entered for any unit. Orders are remembered from turn to turn, and new orders can be added in future turns after watching an animation of any remaining ones. The orders for any given unit can be cancelled by pressing the space bar.

After entering orders, the combat phase is started by pressing the Start function key. Units will attempt to follow their orders to the greatest extent possible, delayed by terrain, blocking friendly units, or combat with enemy units. The screen shows combat by flashing the "attacked" unit, which might be forced to retreat, or be destroyed outright. When all possible movement and combat is exhausted, the game returns to the order-entry phase. Each turn represents one week in-game time, and the game ends on March 29, 1942, after 41 turns.[4] The highest possible score is 255, and the documentation suggests that any score above 100 is good. Computer Gaming World estimated that the actual German army in 1941 scored 110 to 120.[5]

The game engine includes a number of features that increases the "depth" compared to other wargames of the era, such as zones of control,[6] which allows front lines to be constructed without requiring contiguous lines of units. This includes muster and combat strengths, which simulates losses due to combat, and reinforcements that slowly returns a unit to muster strength over time. Supply lines are also simulated, and surrounding the enemy to cut off their supplies is an important strategy for the human player, who faces an overwhelming enemy numerical superiority.

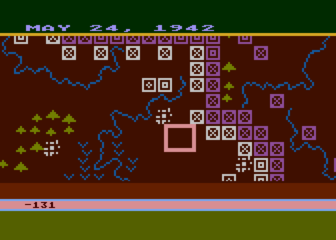

The most obvious effect in terms of gameplay is the changing of the seasons, with the rivers and land freezing from north to south. Winter and spring weather dramatically reduces mobility and supply levels, at which point the German side is forced into a purely defensive role. If the player can survive the winter, the arrival of spring offers a renewed offensive capability, but only for a short period before the game ends.

AI

In an example of pondering, the computer AI calculates its moves during the period between vertical blank interrupts (VBI). The rest of the game, what the user sees, is run during the VBI period of a few hundred cycles. According to Crawford in Chris Crawford on Game Design, the system starts with a basic "plan" and then applies any available cycles to trying variations on that plan, selecting higher-valued outcomes. A few thousand cycles are available between each VBI, so given a typical order-entry phase of a minute, the computer has millions of cycles to spend on refining its plan.

The AI is based on three basic measures of the game state: The strategic situation which attempts to take and hold cities, the tactical situation which attempts to block player movements, and the overall arrangement of the front line.[7] The AI firsts attempt to build a continuous front line in an attempt to prevent encirclements, it then sends additional units on intercept courses to block player movements, and finally any remaining units are sent to undefended cities.

Although the AI is not particularly strong, it has greater numbers. Against a player "playing fair" the computer can put up a credible defence. Direct fights are hopeless for the player, as newly arriving units eventually overwhelm the German forces. Crawford spent considerable time "tuning" the arrival of new units to balance the gameplay,[8] and warned that a player who attempted to overwhelm the Russians with tanks is "guaranteed to lose. What you are supposed to do is maneuver, encircle, demoralize, and defeat".[9] In typical games, the player attempts to break eastward and encircle the ever-growing block of Russian units. The Russians are short of the highly mobile armored units early in the game, so it is possible to outmaneuver them and cut off their supplies, drawn from the far right edge of the screen.

According to Crawford, Eastern Front is an example of a game with a sharp jump in the learning curve; "apparently there is just one trick in the game, mastery of which guarantees mastery of the game". While he did not specify the trick,[10] there are ways to trick the AI. One is to break the German forces into two blocks, and then advance them on alternate turns. The tactical part of the AI attempts to intercept these movements, sending its mobile forces first one way, then the other, never actually making contact. Another strategy is to keep flanking forces behind a spearhead, which the AI would attempt to block. This results in the computer forces clumping up in front of the Germans, allowing the wings to move in once motion was difficult.

One bug in the first version's game engine was exploited by players. Since the AI calculates its moves while the user entered their orders, reducing the amount of time the user took to plan their own moves reduces the quality of the computer response. This can be reduced to zero by pressing the Start key repeatedly, at which point neither the player or the computer does anything. This way combat during the winter can be avoided entirely, allowing the player to break out the next spring with full-strength units.

Development and versions

Crawford wrote the first version of what he called Ourrah Pobieda (Russian for "Horray for the Motherland!") in May and June 1979 on a Commodore PET using Commodore BASIC. The game was at the time a division-level simulation of combat on the Eastern Front. He described the initial version as "dull, confusing, and slow", and did not return to the project for 15 months. After he began working for Atari, in September 1980 he saw a fellow employee demonstrate smooth scrolling in a text window on an Atari 8-bit and realized the technique's potential for a war game. By December he produced a smoothly scrolling map of Russia, in January 1981 produced a written description of the design for what he by now envisioned as a "48K disk-based game with fabulous graphics", and began working 20 hours a week during nights and weekends to produce a demonstrable game by the Origins Convention in July.[8]

Crawford first playtested the game in May and again found it disappointing. To simplify the project, he reduced the game's scope from the entire 1941-1945 campaign to just the first year; introduced zones of control to reduce the number of units and the burden on the computer's artificial intelligence; and added logistics, which permitted encirclement. Crawford also found that the game fit into 16K RAM instead of 48K, and maintained the size. He distributed the game to other playtesters in June, demonstrated a playable version at Origins, then further refined the game for six weeks by fixing bugs and adjusting game balance.[8] In a 1987 interview, he estimated he had worked a total of 800 hours on Eastern Front, and believed that the game had influenced the industry to simplify user interfaces and prove that there was a market for an "intelligent", non-action game.[11]

Crawford approached Atari about selling the game, but the company felt that wargames for Atari computers would not be popular.[12] He turned to the Atari Program Exchange (APX), a separate Atari group that distributed third-party applications. APX began selling the game—renamed Eastern Front just before completion—in August 1981, and sold over 60,000 copies ($40,000 in royalties to Crawford).[13][8] By 1983 it was APX's best seller,[14] and APX offered a scenario editor by Crawford and user-created scenarios for the game;[15] its manager later said that Eastern Front and De Re Atari "paid the bills, i.e. were our biggest sellers".[16] Crawford stated in 1987 that the game had been the most lucrative for him "by at least a factor of four",[11] and in 1992 that it had sold "fabulously well — far better than anybody (myself included) expected", with most purchasers not traditional wargamers.[17] Crawford released the source code to the game through APX for $49.95,[15] and was surprised that while it sold well, no other game used it.[18] The source code is now available on the internet, allowing it to be examined, although only within the Atari Assembler Editor, perhaps in an emulator.

The game was so successful that Atari asked Crawford to do a conversion to cartridge as an official Atari product. To improve the gameplay he revamped the AI code, and eliminated the ability to "fast forward" the game and avoid combat. Five difficulty levels are added, the "learner" mode with a single German unit in order to teach the user how to use the controls, and each level above that adding more units up to "advanced", which is identical to the original game. In the highest level, "expert", air force corps (Fliegercorp) are added, and the units can be placed in one of several modes; normal, assault, or defend and move. In "expert" the user can also choose to start in either 1941 with the standard opening, or 1942, with fully developed lines deep within Russia. The new version also adds the ability to save and restore games, colored cities to indicate ownership, and added city names to the in-game map (which were previously visible only in the manual). The conversion from APX to official Atari product was rare, although Caverns of Mars and Dandy underwent similar conversions for the same reasons.

Crawford used many of the ideas pioneered in Eastern Front in Legionnaire for Avalon Hill in 1982. Legionnaire uses the same map engine to simulate the Roman legions fighting the barbarians, but modifies it to move units in real time.[19] This makes the game much more difficult to outthink than Eastern Front, as the human user must find the enemy units on the map, plan strategy, and move their units at the same time.

Reception

Eastern Front received critical praise from contemporary magazines. Computer Gaming World in 1981 called it "to this date, the most impressive computer wargame on the market". The review praised the graphics and the artificial intelligence, noting its pondering, and suggested that the game would encourage consumers to purchase Atari computers.[20] In 1987 the magazine rated the game five out of five points, stating "obsolete by contemporary programming standards, it is still fun to play",[21] and in 1993 the magazine rated the game four stars out of five.[22] Creative Computing called it "one of the very best war games available for a personal computer ... a technical masterpiece", praising its artificial intelligence and "magnificent" scrolling map. The magazine concluded that Eastern Front was "also a virtuoso demonstration of the awesome built-in capabilities of the Atari computer. This game literally could not be done on any other computer in as satisfactory an execution",[23] and named it Game of the Year in 1981.[24]

Jerry White gave the game a rating of 9.3 out of 10 in A.N.A.L.O.G. magazine, calling it "truly magnificent".[1] Compute! called Eastern Front "a paradigm for computer war games" and praised its graphics and gameplay, with the only major criticism being the inability to save and restore a game.[25] InfoWorld rated it "Excellent" overall in December 1981,[26] and later referred to it as one of "... the deepest computer games around."[9] BYTE stated that Eastern Front "is possibly the first fun war game for people who hate war games".[27] The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software 1984 gave the game an overall A rating, calling it "perhaps the best-designed computer war game to appear on any microcomputer to date" and praising the graphics and joystick-driven user interface. The book concluded that it "is the first war game that non-warriors might enjoy ... Highly recommended."[28]

In 1987 Crawford stated that Eastern Front was one of the three games he was proud of, with Legionnaire and Balance of Power.[11] In 2002 GameSpy wrote that it was considered to be one of the first computer wargames that paper-and-pencil wargamers approved of.[6]

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 White, pg. 22

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 131

- ↑ Chris Crawford, "Ga-Ga over Graphics", Works and Days, Volume 22 Issue 43/44 (2004), pg. 113

- ↑ McMahon, pg. 94

- ↑ Proctor, Bob (May–June 1982). "A Beginner's Guide to Strategy and Tactics in Eastern Front". Computer Gaming World. p. 10.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Cervo, Tony (2002). "1981 Winners". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 2006-05-05. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ Overview from examining the source code, available below.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 Crawford, Chris (August 1982). "Eastern Front: A Narrative History". Creative Computing. p. 100. Retrieved 18 November 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Mace, pg. 34

- ↑ Crawford, Chris (December 1982). "Design Techniques and Ideas for Computer Games". BYTE. p. 96. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "Designer Profile: Chris Crawford (Part 2)". Computer Gaming World. Jan–Feb 1987. pp. 56–59. Retrieved 1 November 2013.

- ↑ Hague, see "Why was "Eastern Front" released through the Atari Program Exchange?"

- ↑ Crawford, pg. 257

- ↑ DeWitt, Robert (June 1983). "APX / On top of the heap". Antic. Retrieved 30 October 2013.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 "Eastern Front (1941) Scenario Editor / Eastern Front Scenarios 1942, 1943, 1944 / Source Code for Eastern Front (1941)". APX Product Catalog. Fall 1983. pp. 61–62. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- ↑ Kevin Savetz, "Fred Thorlin: The Big Boss at Atari Program Exchange", April 2000

- ↑ Brooks, M. Evan (1992-08). "Wargaming Personalities Debate Hobby's Future". pp. 114–115. Retrieved 3 July 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Hague, see "Was it your idea to sell the source code?"

- ↑ DeWitt, pg. 34

- ↑ Greenlaw, Stanley (November–December 1981). "Eastern Front". Computer Gaming World (review). pp. 29–30. Retrieved 31 October 2013.

- ↑ Brooks, M. Evan (April 1987). "Kilobyte Was Here!". Computer Gaming World. p. 6.

- ↑ Brooks, M. Evan (1993-09). "Brooks' Book of Wargames: 1900-1950, A-P". Computer Gaming World. p. 118. Retrieved 30 July 2014. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Blank, George (January 1982). "Eastern Front / The Atari Goes to War". Creative Computing. pp. 44–47. Retrieved 30 January 2015.

- ↑ DeWitt, pg. 56

- ↑ McMahon, Edward P. (February 1982). "Review: Eastern Front (1941)". Compute!. p. 94. Retrieved 6 October 2013.

- ↑ David Cortesi, "Eastern Front (1941), wargame from Atari Exchange", InfoWorld, December 7, 1981, pf. 34

- ↑ "The Coinless Arcade". BYTE. December 1981. pp. 38–41. Retrieved 19 October 2013.

- ↑ Stanton, Jeffrey; Wells, Robert P. Ph.D.; Rochowansky, Sandra; Mellid, Michael Ph.D., ed. (1984). The Addison-Wesley Book of Atari Software. Addison-Wesley. p. 184. ISBN 0-201-16454-X.

Bibliography

- Chris Crawford, "Chapter 18. Eastern Front (1941)", Chris Crawford on Game Design, O'Reilly, 2003, pg. 131–137

- Scott Mace, "Chris Crawford's Kingdom", InfoWorld, August 27, 1984, pg. 34

- Jerry White, "Eastern Front", A.N.A.L.O.G. Number 5 (1982), pg. 22

- James Hague, "Interview with Chris Crawford", Halcyon Days

- Robert DeWitt, "With Legionnaire, fight Caeser's battles on Atari", InfoWorld, February 14, 1983, pg. 56

- Edward McMahon, "Review: Eastern Front (1941)", Compute!, February 1982, pg. 94

External links

- Eastern Front at MobyGames

- Eastern Front can be played for free in the browser at the Internet Archive

- atariarchives.com; Eastern Front by Chris Crawford – APX Cat. No. 20050

- atariarchives.com; source code for Eastern Front – APX Cat. No. 20095

- atarimania.com; Atari Eastern Front (1941) information and scans (APX package).

- Atari Age; Eastern Front (1941), Atari – RX8039.