East Coast Main Line

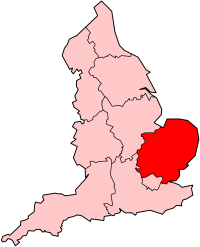

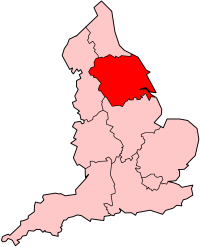

The East Coast Main Line (ECML) is a 393-mile long (632 km)[2] railway[1] link between London and Edinburgh via Peterborough, Doncaster, Wakefield, Leeds, York, Darlington and Newcastle, the line is electrified along the whole route. Services north of Edinburgh to Aberdeen and Inverness use diesel trains. The main franchise on the line is operated by Virgin Trains East Coast.

The route forms a key artery on the eastern side of Great Britain and is broadly paralleled by the A1 trunk road. It links London, the South East and East Anglia, with Yorkshire, the North East Regions and Scotland. It also carries key commuter flows for the north side of London. It is, therefore, important to the economic health of several areas of England and Scotland. It also handles cross-country, commuter and local passenger services, and carries heavy tonnages of freight traffic. The route has ELRs ECM1 - ECM9.

Route definition and description

The ECML forms part of Network Rail's Strategic Route G which comprises six separate lines:[3]

- The main line between London King's Cross and Edinburgh Waverley stations, via Stevenage, Peterborough, Grantham, Newark North Gate, Retford, Doncaster, York, Darlington, Durham, Newcastle, Morpeth, Alnmouth, Berwick-upon-Tweed and Dunbar;

- The Doncaster branch of the Wakefield Line, between Doncaster and Leeds, via Wakefield Westgate;

- The Northern City Line from Finsbury Park to Moorgate; and

- The Hertford Loop Line from Alexandra Palace to Stevenage.

- The branch line to North Berwick

- The Dunbar loop

The core part of the route is the main line between King's Cross and Edinburgh, with the Hertford Loop used for local and freight services and the Northern City Line only used on weekdays for inner suburban services.[3]

History

The line was built by three railway companies, each serving their own area, but with the intention of linking up to form the through route that became the East Coast Main Line. From north to south they were

- the North British Railway, from Edinburgh to Berwick-upon-Tweed, completed in 1846,

- the North Eastern Railway from Berwick-upon-Tweed to Shaftholme

- the Great Northern Railway from Shaftholme to Kings Cross, completed in 1850.

When first completed, the GNR made an end-on connection at Askern, famously described by the GNR's chairman as, "a ploughed field four miles north of Doncaster",[4] with the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway, a short section of which was used to reach the NER at Knottingley. In 1871, the route was shortened - NER opened a direct line which ran from an end-on junction with the GNR, at Shaftholme, just south of Askern to Selby and then (once over Selby bridge on the Leeds- Hull Line) direct to York[4]

Realising that through journeys were an important part of their business, the companies established special rolling stock in 1860 on a collaborative basis; it was called the "East Coast Joint Stock".

In 1923 the three companies were grouped into the London and North Eastern Railway (LNER). This later became part of British Railways in 1948.

Numerous alterations to short sections of the original route have taken place, the most notable being the opening of the King Edward VII Bridge in Newcastle upon Tyne in 1906 and the Selby diversion, built to by-pass anticipated mining subsidence from the Selby coalfield and a bottleneck at Selby station. The Selby diversion was opened in 1983 and diverged from the original ECML at Temple Hirst, north of Doncaster, and joined the Leeds to York Line at Colton Junction.

.jpg)

The ECML has been the backdrop for a number of famous rail journeys and locomotives. The line was worked for many years by Pacific locomotives designed by Gresley, including the famous steam locomotives "Flying Scotsman" and "Mallard". Mallard achieved a world record speed for a steam locomotive, at 126 miles per hour (203 km/h) and this record was never beaten. It made the run on the Grantham-to-Peterborough section, on the descent of Stoke Bank.

Steam locomotives were replaced by Diesel electrics in the early 1960s, when the purpose-built Deltic locomotive was developed by English Electric. The prototype was successful and a fleet of 22 locomotives was built, to handle all the important express traffic. The Class 55s were powered by two engines originally developed for fast torpedo boats, and the configuration of the engines led to the Deltic name. Their characteristic throaty exhaust roar and chubby body outline made them unmistakable in service. The Class 55 was for a time the most powerful diesel locomotive in service in Britain, at 3,300 hp (2,500 kW).

It was just after the Deltics were introduced that the first sections of the East Coast Main Line were upgraded to officially allow 100 miles per hour (160 km/h) running. The first length to be cleared for the new higher speed was a 17 miles (27 km) stretch between Peterborough and Grantham on 15 June 1965, the second was 12 miles (19 km) between Grantham and Newark.[5]

As the demand for higher speed intensified, the Deltics were eventually superseded by the High Speed Train (HST), introduced between 1976 and 1981 and still in service in 2013 (re-engined, with the original Paxman Valenta power units replaced by MTU engines).

A prototype of the HST, the Class 41 achieved 143 mph (230 km/h) on the line in 1973.[6][7] Current UK legislation requires in-cab signalling for speeds of over 125 mph which is the primary reason preventing the InterCity 225 train-sets from operating at their design speed of 140 mph (225 km/h) in normal service.

A secondary factor was that the signalling technology of the time was insufficiently advanced to allow detection of two broken rails on the line on which the train was operating.[8]

Before the present in-cab regulations came in, British Rail experimented with 140 mph running by introducing a fifth, flashing green signalling aspect on track between New England North and Stoke Tunnel. The fifth aspect is still shown in normal service and appears when the next signal is showing a green (or another flashing green) aspect and the signal section is clear, which ensures that there is sufficient braking distance to bring a train to a stand from 140 mph.[6] Locomotives have operated on the ECML at speeds of up to 161.7 mph (260.2 km/h) in test runs.[9]

Electrification

The ECML was electrified using 25 kV AC overhead lines in two phases between 1976 and 1991: The first phase between London (Kings Cross) and Hitchin was carried out between 1976 and 1978 as part of the Great Northern Suburban Electrification Project. This included the Hertford Loop Line.[10] The second phase began in 1984, when authority was given to electrify to Edinburgh and Leeds. Construction began in 1985, and the section between Hitchin and Peterborough was completed in 1987, Doncaster and York were reached in 1989. By 1990 electrification had reached Newcastle, and in 1991 Edinburgh. At the peak of the electrification project during the late 1980s, it was claimed to be the "longest construction site in the world" at over 250 miles (400 km). The current InterCity 225 rolling stock was introduced in 1990 to work the electrified line.[11]

Infrastructure

The line is mainly four tracks from London to Stoke Tunnel, south of Grantham. However, there are two major twin-track sections: the first of these is near Welwyn North Station as it crosses the Digswell Viaduct and passes through two tunnels; the second is a section around 'Stilton Fen', between Fletton Junction near Peterborough, and southwards towards Holme Junction; furthermore, the section between Holme Junction south to Huntingdon is mostly triple track. North of Grantham the route is twin track except for four-track sections at Retford around Doncaster, between Colton Junction (which is south of York), Thirsk and Northallerton, and another at Newcastle.[12]

The main route is electrified along the full route and only the line between Leeds and York (Neville Hill Depot to Colton Junction) is non-electrified.[12] However, this diversionary route will be electrified as part of the transpennine electrification scheme, to be completed by December 2018.

With most the of the line rated for 125 mph (200 km/h) operation, the ECML was the fastest main line in the UK until the opening of High Speed 1. These relatively high speeds are possible because much of the ECML travels on fairly straight track on the flatter, eastern regions of England, through Lincolnshire and Cambridgeshire, though there are significant speed restrictions (due to curvature) particularly North of Darlington and between Doncaster and Leeds. By contrast, the West Coast Main Line has to traverse the Trent Valley and the mountains of Cumbria, leading to many more curves and a lower general speed limit of 110 mph (180 km/h). Speeds on the WCML have been increased in recent years with the introduction of tilting Pendolino trains and now match the 125 mph speeds available on the ECML.

Rolling stock

Most express passenger services use the InterCity 225 rolling stock. Some diesels still operate on line, including:

- CrossCountry's Class 220 Voyagers, Class 221 Super Voyagers and, occasionally, HST sets that CrossCountry introduced after it took over from Virgin CrossCountry. (Joining the ECML at York and continuing to Newcastle, Edinburgh, Glasgow, Dundee and Aberdeen)

- First Hull Trains Class 180 Adelantes (Kings Cross–Hull)

- Virgin Trains East Coast HST sets work to Inverness and Aberdeen, as well as daily services to Lincoln, Hull and Harrogate .

- East Midlands Trains operates a limited service of HSTs over a portion of the route between Doncaster and Leeds, and a summer Saturday service with Class 222 Meridians from York and Scarborough to London St Pancras, and back.

- Grand Central's HSTs and Class 180 Zephyrs (Kings Cross–Sunderland/Bradford)

Operators

The line's current principal operator is Virgin Trains East Coast, whose services include regular trains between King's Cross, the East Midlands, Yorkshire, the North East of England and Scotland. Virgin Trains East Coast is jointly operated by Stagecoach Group and Virgin Group and took over from East Coast on 1 March 2015. Other operators of passenger trains on the line are:

- Great Northern: long distance services between King's Cross, Peterborough, Cambridge and King's Lynn and commuter services between Moorgate and Stevenage via either Welwyn Garden City or the Hertford Loop.

- First Hull Trains: operate six trains per day between Kings Cross and Hull and one per day between Kings Cross and Beverley on weekdays, whilst on weekends there are seven trains a day between Kings Cross and Hull.

- East Midlands Trains: local services between Grantham and Peterborough, part of the service that runs between Liverpool Lime Street and Norwich, as well as infrequent services between London-York and Scarborough, extensions of services running to/from Sheffield, Leicester and London St Pancras.

- CrossCountry: cross-country services north of Sheffield are routed via either Leeds or Doncaster. Leeds trains use the ECML between Wakefield Westgate and Leeds and then again north of York. Doncaster trains use the ECML north of Doncaster. Services run to and beyond Edinburgh. Occasional services run from Doncaster to Leeds before rejoining the ECML at York.

- First TransPennine Express: between Liverpool Lime Street and Newcastle also between Manchester Airport and Middlesbrough before they divert off the ECML to Middlesbrough via Yarm.

- Northern Rail: suburban services from Doncaster to Leeds and Chathill to Newcastle via Morpeth railway station and infrequent services between Newcastle and Darlington that continue to Middlesbrough and Saltburn. Services between Selby and York also use the line from Hambleton Junction to York.

- Abellio ScotRail: services from Edinburgh Waverley to North Berwick and Dunbar. The overnight Caledonian Sleeper occasionally uses the ECML when engineering works prevent it from using its normal train path on the WCML.

- Grand Central: intercity operate five daily services between Kings Cross and Sunderland, branching off the main line at Northallerton; and four daily services between Kings Cross and Bradford, branching off at Doncaster.

Eurostar previously held the rights to run five trains a day on the line for services from continental Europe to cities north of London, as part of the Regional Eurostar plan, although such services have never been run.[13]

DB Schenker, FirstGBRf, Freightliner, Freightliner Heavy Haul and Direct Rail Services operate freight services.

Development

Capacity problems

The ECML is one of the busiest lines on the British rail network and there is currently insufficient capacity on parts of the line to satisfy all the requirements of both passenger and freight operators.

There are bottlenecks at the following locations:

- The section of twin track within a four-line section at Welwyn North over the Digswell Viaduct and through the Welwyn tunnels[14]

- The twin and triple track sections located between Huntingdon and Peterborough.[15]

- Just north of Newark station at a flat crossing with the Nottingham to Lincoln Line.[16]

- The section of double track between Peterborough and Doncaster.[15]

- Doncaster station has limited facilities for terminating branch trains on the up side of the station.

- South of Newcastle to Northallerton (which is also predominately double track), leading to proposals to reopen the Leamside line to passenger and freight traffic.[15][17]

Rail services are vulnerable during high winds and there have been several de-wirements over the years due to the unusually wide spacing between the supporting masts of the overhead lines. The other cost-cutting measure was the use of headspan catenary support systems over the quadruple tracked sections which are not as robust as the older portal and TTC type designs used on the WCML. This was a result of extreme pressure from the Department for Transport to reduce avoidable costs when the line was originally electrified between 1985 and 1990.[18]

Recent developments

- The Allington Chord was constructed near Grantham in 2006, allowing services between Nottingham and Skegness to call at Grantham without having to use the ECML, trains now passing under the line. This provided sufficient extra capacity for National Express East Coast to run 12 additional services between Leeds and London each day.[19][20]

- A new platform at London Kings Cross was opened on 20 May 2010. This was originally to be called "Platform Y".[21] Instead it has been named Platform 0 to avoid confusion of lettered and numbered platforms.

- The southern side of York station was given new track, OLE and signalling systems. An additional line (a fourth track at Holgate Junction) and new junction were completed in early 2011. This work helped to remove one of the bottlenecks on the East Coast Main Line. Previously, trains would sometimes have to wait before entering the station. The improvement allows for better flow of trains in and out of the station.[21][22][23]

- Provision of a grade-separated junction to the north of Hitchin (the Hitchin flyover) enabling down Cambridge trains to cross the main line[21][24][25] The work was completed by 26 June 2013[26]

- Major remodelling of Peterborough station was completed during early 2014 providing three platform faces for services in the up direction towards London and two for ECML services travelling north on the down lines. An additional two platform faces are also available for Cross Country services to and from stations to the east of Peterborough.[21]

- A new flyover just south of Joan Croft level crossing in South Yorkshire to allow freight trains from Immingham to pass over the line on their way to Eggborough and Drax power stations, was completed in very early 2014. The project, known as the North Doncaster Chord, also replaced the level crossing on a minor road with a new overbridge just to the north of the original crossing point.[21][23]

- Renewal and gauge enhancement of the GNGE (Great Northern - Great Eastern) Line which runs parallel to the ECML between Peterborough and Doncaster. This will remove freight traffic from a heavily congested section of the ECML.

- A new Rail Operating Centre (ROC), with training facilities, opened in early 2014 at the "Engineer's Triangle" in York. The ROC will enable signalling and day-to-day operations of the route to be undertaken in a single location. Signalling control/traffic management using ERTMS is scheduled to be introduced from 2020 on on the ECML between London Kings Cross and Doncaster - managed from the York ROC.

Planned developments

Over the years successive infrastructure managers have developed schemes for route improvements.[12] The most recent of which is the £240 million "ECML Connectivity Fund" included in the 2012 HLOS with the objective of increasing capacity and reducing journey times. Current plans include the following:

- Connection of the ECML to Thameslink as part of the Thameslink Programme (for Thameslink and Great Northern commuter services to be extended to south London).

- Full reversible signalling over the Stilton Fen section

- Power supply upgrades (PSU) along the route, including some overhead lines (OLE) support improvements and rewiring of the contact and catenary wires.

- Re-quadrupling of the route between Huntingdon and Holme which was rationalised in the 1980s (part of the ECML Connectivity programme)

- Power supply enhancement on the diversionary Hertford Loop route

- Level crossing closures between Kings Cross and Doncaster

- Additional down platform and turnback facility at Stevenage (part of the ECML Connectivity programme)

- Provision of a new Up bay platform (Platform 0) at Doncaster station (part of the ECML Connectivity programme)

- Enhanced passenger access to the platforms at Peterborough and Stevenage

- Modified north throat at York Station to reduce congestion for services calling at Platforms 9 - 11 (part of the ECML Connectivity programme)

- Increasing maximum speeds on the fast lines between Woolmer Green and Dalton-on-Tees up to 140 mph (225 km/h) in conjunction with the introduction of the Intercity Express Programme, level crossing closures, ETRMS fitments, OLE rewiring and the OLE PSU.

- Remodelling north of Peterborough to provide a new grade separated junction at Werrington to allow freight services to join or be diverted off the ECML to/from the GNGE without crossing all four tracks at level.

- Upgrading of Shaftholme Junction from 100 mph to 125 mph.

- Replacement of the Newark North Gate Flat Crossing with a flyover (scheme developed currently to GRIP Stage 2)[27]

- The line between London King's Cross to the approach of Doncaster will be signalled with Level 2 ERTMS. The target date for operational ERTMS services is December 2018 with completion in 2020[28]

- An £8.6 million redevelopment of Newcastle Central Station will be undertaken enhancing the existing station and provide a state-of-the-art station for thousands of passengers.[29]

Accidents

The ECML has been witness to a number of incidents resulting in death and serious injury:

| Title | Date | Killed | Injured | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Welwyn Tunnel rail crash | 9 June 1866 | 2 | 2 | Three-train collision in tunnel, caused by guard's failure to protect train and signalling communications error |

| Hatfield rail crash (1870) | 26 December 1870 | 8 | 3 | Wheel disintegrated causing derailment killing six passengers and two bystanders |

| Abbots Ripton rail disaster | 21 January 1876 | 13 | 59 | Flying Scotsman crashed during a blizzard. |

| Morpeth rail crash (1877) | 25 March 1877 | 5 | 17 | Derailment caused by faulty track. |

| Thirsk rail crash (1892) | 2 November 1892 | 10 | 43 | Signalman forgot about a goods train standing at his box and accepted the Scotch Express onto his line with inevitable consequences. |

| Grantham rail accident | 19 August 1906 | 14 | 17 | Runaway or overspeed on junction curve causing derailment - no definite cause established. |

| Welwyn Garden City rail crash | 15 June 1935 | 14 | 29 | Two trains collided due to a signaller's error. |

| King's Cross railway accident | 4 February 1945 | 2 | 26 | Train slipped on gradient and slid back into station. |

| Potters Bar rail crash | 10 February 1946 | 2 | 17 | Local train hit buffers fouling main line with wreckage hit by two further trains. |

| Goswick rail crash | 26 October 1947 | 28 | 65 | Edinburgh-London Flying Scotsman failed to slow down for a diversion and derailed. Signal passed at danger |

| Doncaster rail crash | 16 March 1951 | 14 | 12 | Train derailed south the station and struck a bridge pier. |

| Goswick Goods train derailment | 28 October 1953 | 1 | 'Glasgow to Colchester' Goods train was derailed at Goswick.[30][31] | |

| Connington South rail crash | 5 March 1967 | 5 | 18 | Express train was derailed. |

| Thirsk rail crash | 31 July 1967 | 7 | 45 | Cement train derailed and hit by North bound express hauled by prototype locomotive. DP2 |

| Morpeth rail crash (1969) | 7 May 1969 | 6 | 46 | Excessive speed on curve. |

| Penmanshiel Tunnel collapse | 17 March 1979 | 2 | Two workers killed when the tunnel collapsed during engineering works. | |

| Morpeth rail crash (1984) | 24 June 1984 | 35 | Excessive speed on curve. | |

| Newcastle Central railway station collision | 30 November 1989 | 15 | Two InterCity expresses collided.[32] | |

| Morpeth rail crash (1992) | 13 November 1992 | 1 | Collision between two freight trains. | |

| Morpeth rail crash (1994) | 27 June 1994 | 1 | Excessive speed led to the locomotive and the majority of carriages overturning. | |

| Hatfield rail crash | 17 October 2000 | 4 | 70 | InterCity 225 derailed due to a failure to replace a fractured rail. The accident highlighted poor management at Railtrack and led to its partial re-nationalisation. |

| Great Heck rail crash | 28 February 2001 | 10 | 82 | A Land Rover Defender swerved down an embankment off the M62 motorway into the path of a southbound GNER Intercity 225. |

| Potters Bar rail crash (2002) | 10 May 2002 | 7 | 70 | Derailment caused by a badly maintained set of points. Resulted in the end of the use of external contractors for routine maintenance. |

| Copmanthorpe rail crash | 25 September 2006 | 1 | A car crashed through a fence onto the line. |

Passenger volume

| Station usage | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Station Name | 2002–03 | 2004–05 | 2005–06 | 2006–07 | 2007–08 | 2008–09 | 2009–10 | 2010–11 | 2011–12 | 2012–13 | 2013–14 |

| Edinburgh to Doncaster | |||||||||||

| Edinburgh Waverley | 12,470,767 | 14,219,772 | 14,645,022 | 15,285,837 | 16,169,294 | 17,571,392 | 19,312,458 | 19,957,346 | |||

| Musselburgh | 161,121 | 170,852 | 193,386 | 202,895 | 306,185 | 385,274 | 389,240 | 364,690 | |||

| Wallyford | 90,351 | 110,686 | 126,719 | 135,819 | 159,949 | 209,260 | 227,874 | 221,772 | |||

| Prestonpans | 91,789 | 108,398 | 129,192 | 142,604 | 170,388 | 192,574 | 202,296 | 206,808 | |||

| Longniddry | 117,121 | 122,678 | 135,040 | 140,490 | 161,410 | 165,716 | 157,908 | 154,040 | |||

| Drem | 73,871 | 78,009 | 80,563 | 84,905 | 99,735 | 109,418 | 107,844 | 100,208 | |||

| Dunbar | 224,552 | 266,142 | 288,282 | 299,172 | 332,377 | 339,094 | 318,976 | 333,916 | |||

| Berwick-upon-Tweed | 331,108 | 378,727 | 395,000 | 380,555 | 391,772 | 405,828 | 419,454 | 454,568 | |||

| Chathill | 1,482 | 1,503 | 2,279 | 1,037 | 1,847 | 1,864 | 2,612 | 2,642 | |||

| Alnmouth | 86,436 | 134,902 | 165,049 | 172,170 | 181,912 | 197,222 | 192,380 | 214,230 | |||

| Acklington | 727 | 917 | 1,137 | 985 | 948 | 778 | 268 | 108 | |||

| Widdrington | 5,481 | 7,740 | 6,618 | 5,523 | 4,707 | 6,314 | 6,398 | 5,124 | |||

| Pegswood | 2,417 | 3,564 | 2,940 | 2,281 | 2,332 | 2,788 | 2,688 | 1,102 | |||

| Morpeth | 123,142 | 163,627 | 177,497 | 188,798 | 206,458 | 226,652 | 228,252 | 243,982 | |||

| Cramlington | 40,886 | 68,472 | 77,304 | 83,314 | 87,737 | 89,828 | 87,374 | 85,454 | |||

| Manors | 1,409 | 1,882 | 1,390 | 1,002 | 1,406 | 2,574 | 2,998 | 2,976 | |||

| Newcastle Central | 4,869,662 | 5,728,348 | 6,108,240 | 6,230,498 | 6,447,267 | 7,098,624 | 7,163,284 | 7,500,338 | |||

| Chester-le-Street | 86,686 | 126,033 | 151,486 | 160,799 | 192,519 | 186,930 | 197,398 | 205,572 | |||

| Durham | 1,359,425 | 1,649,935 | 1,739,801 | 1,774,271 | 1,858,078 | 1,996,852 | 2,051,432 | 2,180,044 | |||

| Darlington | 1,509,282 | 1,795,683 | 1,906,131 | 2,013,516 | 2,099,480 | 2,184,436 | 2,164,428 | 2,209,274 | |||

| Northallerton | 293,137 | 380,622 | 413,038 | 453,459 | 488,647 | 531,676 | 544,070 | 556,990 | |||

| Thirsk | 124,877 | 142,359 | 147,333 | 148,260 | 161,474 | 173,944 | 174,826 | 189,288 | |||

| York | 4,985,396 | 5,795,978 | 6,148,333 | 6,363,387 | 6,534,388 | 6,802,004 | 6,855,682 | 7,173,016 | |||

| Leeds to Doncaster | |||||||||||

| Leeds | 11,285,693 | 14,733,503 | 16,059,517 | 17,356,732 | 18,121,572 | 22,421,732 | 21,978,372 | 24,491,616 | |||

| Outwood | 108,221 | 166,801 | 187,314 | 208,174 | 211,079 | 301,388 | 299,434 | 354,792 | |||

| Wakefield Westgate | 1,451,587 | 1,760,373 | 1,846,988 | 1,877,981 | 1,610,947 | 2,017,854 | 1,866,320 | 2,148,410 | |||

| Sandal and Agbrigg | 86,415 | 97,328 | 107,190 | 118,718 | 123,387 | 162,448 | 158,610 | 180,046 | |||

| Fitzwilliam | 79,428 | 105,216 | 116,088 | 126,419 | 142,144 | 180,606 | 178,518 | 195,542 | |||

| South Elmsall | 209,839 | 253,244 | 265,547 | 281,906 | 304,642 | 353,696 | 351,194 | 351,140 | |||

| Adwick | 115,496 | 176,479 | 175,754 | 156,826 | 160,541 | 253,986 | 244,904 | 247,964 | |||

| Bentley (South Yorkshire) | 81,494 | 114,419 | 123,292 | 98,641 | 95,264 | 159,788 | 153,550 | 152,994 | |||

| Doncaster to London Kings Cross | |||||||||||

| Doncaster | 2,347,584 | 2,772,500 | 2,837,400 | 2,790,811 | 2,903,339 | 3,780,314 | 3,676,152 | 3,784,752 | |||

| Retford | 252,113 | 298,398 | 320,410 | 363,084 | 357,812 | 376,066 | 374,322 | 399,996 | |||

| Newark North Gate | 335,126 | 377,172 | 400,286 | 1,187,545 | 923,070 | 960,948 | 924,528 | 976,526 | |||

| Grantham | 806,299 | 917,447 | 935,848 | 999,186 | 1,032,641 | 1,054,634 | 1,033,374 | 1,071,320 | |||

| Peterborough | 3,386,580 | 3,689,729 | 3,720,034 | 3,960,429 | 4,070,725 | 4,099,754 | 3,930,704 | 4,076,724 | |||

| Huntingdon | 1,277,164 | 1,360,288 | 1,373,378 | 1,448,338 | 1,564,270 | 1,592,696 | 1,542,100 | 1,629,780 | |||

| St Neots | 715,993 | 768,708 | 822,064 | 888,971 | 979,356 | 1,029,338 | 1,001,248 | 1,091,388 | |||

| Sandy | 344,127 | 391,673 | 400,416 | 424,161 | 449,698 | 446,186 | 424,906 | 444,122 | |||

| Biggleswade | 582,318 | 638,358 | 653,872 | 689,369 | 751,155 | 734,458 | 703,386 | 739,632 | |||

| Arlesey | 256,882 | 327,106 | 349,725 | 369,425 | 398,128 | 413,870 | 411,056 | 444,680 | |||

| Hitchin | 1,806,889 | 1,948,003 | 2,049,217 | 2,368,121 | 2,543,526 | 2,569,494 | 2,478,832 | 2,594,012 | |||

| Stevenage | 3,267,031 | 3,495,795 | 3,539,052 | 3,968,033 | 4,206,418 | 4,257,732 | 4,093,020 | 4,222,776 | |||

| Knebworth | 328,011 | 344,003 | 343,752 | 392,409 | 457,813 | 480,706 | 471,564 | 494,182 | |||

| Welwyn North | 368,789 | 406,270 | 395,304 | 428,164 | 455,322 | 468,312 | 454,296 | 485,856 | |||

| Welwyn Garden City | 1,717,434 | 2,002,197 | 2,020,502 | 2,322,204 | 2,502,240 | 2,522,398 | 2,385,014 | 2,431,948 | |||

| Hatfield | 1,130,146 | 1,407,219 | 1,429,839 | 1,642,091 | 1,768,214 | 1,904,588 | 1,836,546 | 1,928,032 | |||

| Welham Green | 114,701 | 125,769 | 120,413 | 134,934 | 147,553 | 153,116 | 145,220 | 160,884 | |||

| Brookmans Park | 136,394 | 143,537 | 150,325 | 167,346 | 185,759 | 198,784 | 191,500 | 203,654 | |||

| Potters Bar | 1,382,046 | 1,440,036 | 1,445,179 | 1,604,056 | 1,681,137 | 1,649,420 | 1,569,258 | 1,599,666 | |||

| Hadley Wood | 181,811 | 206,767 | 244,961 | 344,989 | 393,690 | 402,194 | 353,224 | 343,208 | |||

| New Barnet | 658,099 | 673,521 | 674,532 | 1,057,667 | 1,126,244 | 1,013,310 | 1,029,964 | 1,069,706 | |||

| Oakleigh Park | 571,227 | 601,453 | 623,602 | 993,003 | 993,011 | 909,208 | 917,232 | 952,304 | |||

| New Southgate | 291,538 | 291,290 | 299,461 | 476,100 | 550,758 | 498,252 | 512,446 | 553,174 | |||

| Alexandra Palace | 592,357 | 609,875 | 692,845 | 1,042,833 | 1,310,940 | 1,057,712 | 1,063,484 | 1,114,960 | |||

| Hornsey | 391,655 | 362,488 | 381,659 | 737,369 | 1,031,000 | 896,096 | 942,828 | 1,068,740 | |||

| Harringay | 387,794 | 328,145 | 317,815 | 775,050 | 1,102,321 | 901,968 | 963,282 | 1,039,098 | |||

| Finsbury Park | 3,006,865 | 5,021,634 | 5,041,828 | 5,875,109 | 5,545,881 | 5,492,164 | 6,566,019 | 7,337,297 | |||

| London Kings Cross | 19,137,693 | 20,805,979 | 20,301,663 | 22,503,777 | 23,945,017 | 24,641,427 | 24,817,616 | 26,254,644 | |||

| The annual passenger usage is based on sales of tickets in stated financial years from Office of Rail Regulation statistics. The statistics are for passengers arriving and departing from each station and cover twelve month periods that start in April. Please note that methodology may vary year on year. | |||||||||||

Popular culture

The cuttings and tunnel entrances just north of King's Cross make a memorable smoky appearance in the 1955 Ealing comedy film The Ladykillers. Also during the 1950s, the line featured in the 1954 documentary short Elizabethan Express. Later, the 1971 British gangster film Get Carter features a journey from London Kings Cross to Newcastle in the opening credits. The motoring show Top Gear featured a race including LNER A1 60163 Tornado running up this line from London to Edinburgh.

The route has been featured in several train simulator games. Trainz Simulator 2010 features the route between London and York, while Trainz Simulator 12 extends the route to Newcastle. Both routes take place during the 1970s, around the time the InterCity 125 was introduced. This is reinforced by instructions in the driving session included with TS2010 not to move until the guard has locked the doors, since the trains did not have pneumatic locks initially.

King's Cross is also known as the starting point of the Hogwarts Express from the books and films in the Harry Potter series. Within the station concourse there is a tourist attraction of the Platform 9¾ sign and a luggage trolley partially embedded in the station wall with an owl cage and suitcases on it.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Route 5 - West Anglia" (PDF). Network Rail. Retrieved 2009-05-22.

- ↑ East Coast Main Line Rail Route Upgrading, United Kingdom

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Network Rail (31 March 2010). "Route Plans 2010: Route Plan G East Coast & North East" (PDF). p.5. Retrieved 1 August 2012.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Joy, David (1978). A Regional History of the Railways of Great Britain - Volume 8: South and West Yorkshire. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. p. 304. ISBN 0 7153 7783 3.

- ↑ "Railway Magazine". November 1965. p. 858.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Barnett, Roger (June 1992). "British Rail's InterCity 125 and 225" (PDF). UCTC Working Paper No. 114. University of California Transportation Center; University of California, Berkeley. p. 32. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- ↑ Testing the prototype HST in 1973 - Welcome to my testing site. Retrieved 22 September 2012.

- ↑ Heath, Don (August 1994). "Electrification of British Rail's East Coast Main Line". Paper No. 105. Proceedings of the Institute of Civil Engineers (Transportation). p. 232.

- ↑ Keating, Oliver. "The Inter-city 225". High Speed Rail. Retrieved 29 May 2008.

- ↑ "Your NEW Electric Railway, The Great Northern Suburban Electrification" (PDF). British Railways. 1973. Retrieved 18 March 2014.

- ↑ Semmens, P.W.B. (March 1991). Electrifying the East Coast Route: Making of Britain's First 140m.p.h. Railway. Patrick Stephens Ltd. ISBN 978-0850599299.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Route Business Plan" (PDF). Network Rail. 2008.

- ↑ Millward, David (10 April 2006). "'Phantom trains' haunt drive to improve East Coast line". The Daily Telegraph (London). Retrieved 17 June 2008.

- ↑ "Misery line cheers up". BBC Track Record. November 1999. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "East Coast Main Line 2016 Capacity Review". Railway Development Society. February 2011. Retrieved 2 April 2014.

- ↑ "ECML Route Utilisation Strategy: Railfuture Response" (PDF). Railway Development Society. 13 September 2007. Retrieved 28 July 2009.

- ↑ "ECML Route Utilisation Strategy" (PDF). Network Rail. pp. 66, 134. Retrieved 29 July 2009.

- ↑ Wolmar, Christian (2005). On the wrong line: How ideology and incompetence wrecked Britain's railways. London: Aurum. ISBN 978-1-85410-998-9.

- ↑ "New services are just the ticket". BBC News. 13 October 2005. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ↑ "Trains get 6,000 more seats a day". BBC News. 21 May 2007. Retrieved 17 December 2007.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 Pigott, Nick, ed. (March 2010). "Flyovers to go ahead at Hitchin, Ipswich, Shaftholme". The Railway Magazine (London) 156 (1307): 9. ISSN 0033-8923.

- ↑ "Faster trains and more services at York" (Press release). Network Rail. 3 January 2012.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Broadbent, Steve (10 February 2010). "Moving Yorkshire Forward". Rail (637) (Peterborough). p. 62.

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rOZWyzAOTp8

- ↑ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RhMR9lgsrjs

- ↑ http://www.networkrail.co.uk/news/2013/june/Passenger-services-start-using-Hitchin-flyover/

- ↑ "East Midlands Route Utilisation Strategy Draft for Consultation" (PDF). Network Rail. 2009.

- ↑ "ERTMS Deployment in the UK: Re-signalling as a Key Measure to Enhance Rail Operations" (PDF). ERTMS. 2012.

- ↑ "New Era for Newcastle Central Station". EastCoast. 2013.

- ↑ Northumberland Railways - Goswick station

- ↑ Railways Archive - Ministry report.

- ↑ "Chronology of rail crashes". BBC News. 10 May 2002. Retrieved 28 December 2009.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to East Coast Main Line. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||