Early life of Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson (18 September 1709 [O.S. 7 September] – 13 December 1784) was an English author born in Lichfield, Staffordshire. He was a sickly infant who early on began to exhibit the tics that would influence how people viewed him in his later years. From childhood he displayed great intelligence and an eagerness for learning, but his early years were dominated by his family's financial strain and his efforts to establish himself as a school teacher.

After a year spent studying at Pembroke College, Oxford, Johnson was forced to leave by lack of financial support. He tried to find employment as a teacher, but was unable to secure a long-term position. In 1735 he married Elizabeth "Tetty" Porter, a widow 20 years older than himself, and the responsibilities of this marriage made him determined to succeed as an educator. He established his own school, but the venture was unsuccessful. Thereafter, leaving his wife behind in Lichfield, he moved to London, where he spent the rest of his life. In London he began writing essays for The Gentleman's Magazine, and also befriended Richard Savage, a notorious rake and aspiring poet who claimed to be the disavowed son of a nobleman. Eventually he wrote the Life of Mr Richard Savage, his first successful literary biography. He also wrote the powerful poem London, an 18th-century version of Juvenal's Third Satire, as well as the tragic drama Irene, which was not produced until 1749, and even then was not successful.

Johnson began his literary career as a minor Grub Street hack writer, but he went on to make lasting contributions to English literature as a poet, essayist, moralist, novelist, literary critic, biographer, editor and lexicographer. His early works, especially London and Life of Mr Richard Savage, contain Johnson's emerging views on biography, morality, and literature in general.

Parents

Johnson's parents were Michael Johnson, a bookseller, and his wife, Sarah Ford.[1] Michael was the first bookseller of reputation in the Staffordshire community of Lichfield. He also owned a parchment factory, which allowed him to produce his own books. Little is known of his background, except that he and his brothers were apprenticed as booksellers. Michael's father, William Johnson, was described as a "yeoman" and a "gentleman" in the Stationers' Company records, but there is little evidence to suggest that he was from a noble family. William was the first Johnson to move to Lichfield and died shortly thereafter. Michael Johnson, after leaving his apprenticeship at 24, followed in his father's footsteps and took up a job selling books on Sadler Street, Lichfield. Three years later Michael Johnson became warden of a charity known as the Conduit Lands Trust, and shortly afterwards was made churchwarden of St Mary's church.[2]

At the age of 29, Michael Johnson was engaged to be married to a local woman, Mary Neild, but she cancelled the engagement.[3] Twenty years later, in 1706, he married Sarah Ford. She came from a middle-class milling and farming family and was twelve years his junior, daughter of Cornelius Ford. Although both families had money, Samuel Johnson often claimed that he grew up in poverty. It is uncertain what happened between the marriage of his parents and Samuel's birth three years later to provoke a decline in the family's fortunes, but Michael Johnson quickly became overwhelmed with debt from which he was never able to recover.[4]

Childhood

Johnson was born in Lichfield at 4:00 pm on Wednesday, 18 September 1709 at the family home above his father's bookshop, near Market Square, across from St Mary's Church.[1] His mother was 40 when she gave birth, a matter for sufficient concern that George Hector, a "man-midwife" and a surgeon of "great reputation", was brought in to assist during the birth.[5] The baby was named Samuel, after Sarah's brother Samuel Ford.[1] He did not cry and, with doubts surrounding the newborn's health, his aunt claimed "that she would not have picked such a poor creature up in the street".[6] As it was feared the baby might die, the vicar of St Mary's was summoned to perform a baptism.[7] Two godfathers were chosen: Samuel Swynfen, a physician and graduate of Pembroke College, and Richard Wakefield, a lawyer, coroner, and Lichfield town clerk.[8]

Johnson's health improved and he was placed in the nursing care of Joan Marklew. During this period he contracted what is believed to have been scrofula,[9] known at that time as the "King's Evil". Sir John Floyer, a former physician to King Charles II, recommended that the young Johnson should receive the "royal touch",[10] which he received from Queen Anne on 30 March 1712 at St James's Palace. Johnson was given a ribbon in memory of the event, which he claimed to have worn for the rest of his life. However, the ritual was ineffective and an operation was performed that left him with permanent scarring across his face and body.[11] Sarah later gave birth to a second boy, Nathaniel. Having two children put financial strain on the family; Michael was unable to keep on top of the debts he had accumulated over the years, and his family was no longer able to maintain the lifestyle it had previously enjoyed.[12]

When he was a child in petticoats, and had learned to read, Mrs Johnson one morning put the common prayer-book into his hands, pointed to the collect for the day, and said, 'Sam, you must get this by heart.' She went up stairs, leaving him to study it: But by the time she had reached the second floor, she heard him following her. 'What's the matter?' said she. 'I can say it,' he replied; and repeated it distinctly, though he could not have read it over more than twice.[13]

Johnson demonstrated signs of great intelligence as a child, and his parents, to his later disgust, took pleasure in showing off his "newly acquired accomplishments".[14] His education began at the age of three, when his mother had him memorise and recite passages from the Book of Common Prayer.[15] When Johnson turned four, he was sent to a nearby "school" on Dam Street, where "Dame" Anne Oliver, the proprietor, gave lessons to young children in the living-room of a cottage. Johnson especially enjoyed his time with Dame Oliver, later remembering her fondly. At the age of six he was sent to a retired shoemaker to continue his education,[16] and a year later was enrolled at Lichfield Grammar School; he excelled in Latin under Humphrey Hawkins, his teacher in the lower school.[17]

During this time Johnson began exhibiting the tics that would influence how others viewed him in his later years,[18] and which formed the basis for his posthumous diagnosis of Tourette syndrome (TS).[19][20][21] TS develops in childhood;[19] it follows a fairly reliable course in terms of the age of onset and the history of the severity of symptoms. Tics may appear up to the age of eighteen, but the most typical age of onset is from five to seven.[22] Johnson's tics and gesticulations manifested after his childhood scrofula;[18][19][23] studies suggest that environmental and infectious factors—while not causing Tourette's—can affect the severity of the disorder.[24][25] Pearce describes Johnson's birth as a "very difficult and dangerous labour",[20] and adds that Johnson had many illnesses throughout his life: he "suffered from bouts of melancholy, crushing guilt, habitual insomnia, and he endured a morbid fear of loneliness and of dying." He also was "disturbed by scruples of infidelity" from the age of 10.[20]

Although TS caused problems in his private and public life, it lent Johnson "great verbal and vocal energy".[18] He excelled in his education and was promoted to the upper school at the age of nine,[17] to be tutored by Edward Holbrooke.[26] The school was directed by the Reverend John Hunter, a man known for his scholarship and, like Holbrooke, his brutality, which caused Johnson to become dissatisfied with his education.[27] However, during this time he did befriend Edmund Hector, nephew of his "man-midwife" George Hector, and John Taylor, both of whom he remained in contact with throughout his life.[28]

Cornelius Ford

At the age of 16, Johnson was given the opportunity to stay with his cousins, the Fords, at Pedmore, Worcestershire.[29] There he bonded with Cornelius Ford, the son of his mother's brother,[30] and Ford employed his knowledge of the classics to tutor Johnson while he was not attending school. Johnson enjoyed his time with Ford, who encouraged Johnson to pursue his studies and to become a man of letters. Johnson remembered one moment of Ford's teachings: Ford told him to "grasp the leading praecognita of all things... grasps the trunk hard only, and you will shake all the branches".[31] Ford was a successful, well-connected academic, familiar with many society figures such as Alexander Pope.[32]

Ford was also a notorious alcoholic whose excesses contributed to his death six years after Johnson's visit.[32] This event deeply affected Johnson, and he remembered Ford in his Life of Fenton, saying that Ford's abilities, "instead of furnishing convivial merriments to the voluptuous and dissolute, might have enabled him to excel among the virtuous and the wise".[33] Having spent six months with his cousins, Johnson returned to Lichfield, but Hunter, "angered by the impertinence of this long absence", refused to allow him to continue at the grammar school.[34]

Unable to return to Lichfield Grammar School, Johnson was enrolled, with the help of Ford and his half-brother Gregory Hickman, into the King Edward VI grammar school at Stourbridge. The headmaster was John Wentworth, and he took care to work with Johnson on his translation exercises.[35] Because the school was located near Pedmore, Johnson was able to spend more time with the Fords and get to know his other relatives in the area.[34] During this time he began writing poems and produced many verse translations.[36] However, he spent only six months at Stourbridge before returning once again to his parents' home in 1727. When Boswell was writing his Life of Samuel Johnson, he was told by Johnson's school friend Edmund Hector Johnson's leaving the Stourbridge school was due in part to a fight Johnson and Wentworth had over Latin grammar.[37] For companionship, Johnson spent time with Hector and John Taylor, two of his schoolfriends, and he soon fell in love with Hector's younger sister, Ann. This first love was not to last, and Johnson later claimed to Boswell, "She was the first woman with whom I was in love. It dropped out of my head imperceptibly, but she and I shall always have a kindness for each other."[38]

Johnson's future now began to look uncertain, as his father was deeply in debt.[38] To earn money, Johnson stitched books for his father, although poor eyesight—a result of his childhood illness—meant he eschewed the work involved. It is possible that Johnson spent most of his time in his father's bookshop reading various works and building his literary knowledge. During this time, Johnson met Gilbert Walmesley, the Registrar of the Ecclesiastical Court and a frequent visitor to the bookshop.[39] Walmesley took a liking to Johnson, and the two discussed various intellectual topics during the two years Johnson spent working in the shop.[40] Their relationship was soon put on hold; Sarah Johnson's cousin, Elizabeth Harriotts, died in February 1728 and left her £40 (about £4,700 as of 2015), which was used to send Johnson back to school.[41][42]

College

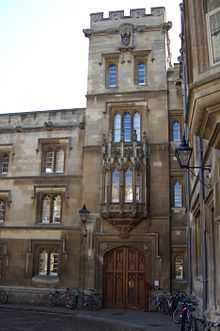

On 31 October 1728, a few weeks after he turned 19, Johnson entered Pembroke College, Oxford as a fellow-commoner.[43] The inheritance did not cover all of his expenses at Pembroke, but Andrew Corbet, a friend and student at Pembroke, offered to make up the deficit. Corbet left Pembroke soon after Johnson arrived, so this source of aid disappeared. To meet the expenses, Michael Johnson allowed his son to borrow a hundred books from his bookshop, at a great cost to himself, and these books were not fully returned to Michael until many years later.[44]

On the day of Johnson's entrance interview for Pembroke, his anxious father introduced him to his future tutor, William Jorden, hoping to make an impression.[45] During the interview, his father was "very full of the merits of his son, and told the company he was a good scholar, and a poet, and wrote Latin verses", which caused Johnson significant embarrassment.[46] Michael's praise was unnecessary; Johnson's interview went so well that one of the interviewers, a 26-year-old William Adams (Jorden's cousin, later Master of Pembroke), claimed that Johnson was "the best qualified for the University that he had ever known come there".[47] Throughout the interview, Johnson sat quietly while listening to his father and the interviewers, until he interrupted and quoted Macrobius.[46] The interviewers were surprised that "a School-boy should know Macrobius", and he was accepted immediately.[48]

At Pembroke, Johnson made many friends, but neglected many of the mandatory lectures, and ignored calls for poems. He did complete one poem, the first of his tutorial exercises, on which he spent comparable time, and which provoked surprise and applause.[49] He was later asked by his tutor to produce a Latin translation of Alexander Pope's Messiah as a Christmas exercise.[50] Johnson completed half of the translation in one afternoon and the rest the following morning. Although the poem brought him praise, it did not bring the material benefit he had hoped for. The poem was brought to Pope's attention; according to Sir John Hawkins, Pope claimed that he could not tell if it was the original or not. However, Johnson's friend John Taylor dismissed this "praise" because Johnson's father had already published the translation before Johnson sent a copy to Pope, and Pope could have been remarking about it being a duplication of the published edition.[51]

Dr Adams told me that Johnson, while he was at Pembroke College, 'was caressed and loved by all about him, was a gay and frolicksome fellow, and passed there the happiest part of his life.' But this is a striking proof of the fallacy of appearances, and how little any of us know of the real internal state even of those whom we see most frequently; for the truth is, that he was then depressed by poverty, and irritated by disease. When I mentioned to him this account as given me by Dr Adams, he said, 'Ah, Sir, I was mad and violent. It was bitterness which they mistook for frolick. I was miserably poor, and I thought to fight my way by my literature and my wit; so I disregarded all power and all authority.'[52]

Regardless, Pope remarked that the work was very finely done, but that did not prevent Johnson from being violently angry at his father's actions in preempting his sending Pope a copy of the poem. The poem later appeared in Miscellany of Poems (1731), edited by John Husbands, a Pembroke tutor, and is the earliest surviving publication of any of Johnson's writings. Johnson spent the rest of his time studying, even over the Christmas vacation. He drafted a "plan of study" called "Adversaria", which was left unfinished, and used his time to learn French while working on his knowledge of Greek.[53]

Although he later praised Jorden, Johnson came to odds with him over what he considered to be Jorden's "meanness" of abilities.[54] He discouraged his friend Taylor, who came to Pembroke in March, from having Jorden as his tutor, and Taylor was soon encouraged to go to Christ Church to be taught by Edmund Bateman. Johnson appreciated Bateman's skill as a lecturer, and he would often travel to meet Taylor to discuss the lectures.[55] However, Johnson lacked the funds to even replace his shoes, and so he started to make the journey barefoot. In response, those of Christ Church began to mock Johnson, and he soon kept to his own room for the rest of his time at Pembroke, with Taylor visiting him instead.[56]

After thirteen months, poverty forced Johnson to leave Oxford without taking a degree, and he returned to Lichfield.[42] During his last weeks at Oxford, Jorden left Pembroke, and Johnson was given William Adams as a tutor in his place. He enjoyed Adams as a tutor, but by December, Johnson was already a quarter behind in his student fees, and he was forced to return home. He left behind many of the books that his father had previously lent him, both because he could not afford the expense of transporting all of them and as a symbolic gesture that he hoped to return to the school soon.[57]

Early career

There is little record of Johnson's life between the end of 1729 and 1731; he most likely lived with his parents when experiencing bouts of mental anguish and physical pains.[58] After these years of illness, his tics and gesticulations associated with TS became more noticeable and were "commented on by many observers".[59] To further complicate Johnson's life, his father was deeply in debt by 1731 and had lost much of his standing in Lichfield. An usher's position became available at Stourbridge Grammar School, but Johnson's lack of a degree saw him passed over, on 6 September 1731.[58] Instead, he stayed at the home of Gregory Hickman, Cornelius Ford's half brother, writing poetry. It was there that he heard the devastating news that Cornelius had died in London, on 22 August 1731; later, in his personal "Annales", he pointed to that moment as one of the most important of his life.[60]

At about the same time, Johnson's father became ill; he developed an "inflammatory fever" by the end of the year.[61] He died in December 1731 and was buried at St. Michael's Church on 7 December 1731. He left no will, and Johnson received only £20 from Michael's estate of £60 (£8.6 thousand as of 2015).[41][61] In an act "almost like religious penance", Johnson honoured his father's memory 50 years later by returning to his bookstall in Uttoxeter to make amends for his refusal to work the stall while his father lay dying.[62] Richard Warner kept Johnson's account of the scene:

... a postchaise to Uttoxeter, and going into the market at the time of high business, uncovered my head, and stood with it bare an hour before the stall which my father had formerly used, exposed to the sneers of the standers-by and the inclemency of the weather.[63]

Johnson eventually found employment as undermaster at a school in Market Bosworth, Leicestershire. He was paid £20 a year (£2.9 thousand as of 2015), enough to support himself.[41] The school was run by Sir Wolstan Dixie, who allowed Johnson to teach even though he did not have a degree. The unconventional Dixie allowed Johnson to live in his own mansion, Bosworth Hall.[64] Although the arrangement may seem congenial, Johnson was treated as "a kind of domestick chaplain, so far, at least, as to say grace at table, but was treated with what he represented as intolerable harshness; and, after suffering for a few months such complicated misery, he relinquished a situation which all his life afterwards he recollected with the strongest aversion, and even a degree of horrour".[65] Still, Johnson found pleasure in teaching even though he thought it boring. By June 1732, he had returned home, and, after a fight with Dixie, quit the school.[66]

Johnson spent the rest of his time at Lichfield looking for a position at the other local schools, and, after being turned down for a position in Ashbourne, he spent his time with his friend, Hector.[67] Hector lived in the home of Thomas Warren, on High Street Birmingham, and Johnson was invited to stay there as a guest in the autumn of 1732. Warren was at that time starting his Birmingham Journal, and he enlisted Johnson's help, although no copies of the essays he wrote for the paper now survive.[68] His stay with Hector and Warren was not to last, and Johnson moved into the house of a man named Jarvis on 1 June 1733.[69] During this time, Johnson started to slip into a "state of 'absence'" and he began to treat his friends with "abuse".[70]

His connection with Warren continued to grow, and Johnson proposed to translate Jeronimo Lobo's account of the Abyssinians.[71] Johnson read Abbe Joachim Le Grand's French translations, and he thought that a shorter version might be "useful and profitable".[72] He began work on the edition and a finished section was taken to be printed during the winter of 1733–1734. Johnson's nerves got the best of him, and after a breakdown he was unable to continue working, but felt obligated to meet his contract.[73] To finish the rest, Johnson dictated directly to Hector, who then took the copy to the printer and made any corrections. It amounted to a month's work, and, a year later, his A Voyage to Abyssinia was finally published.[72]

Johnson returned to Lichfield in February 1734, where he began an annotated edition of Poliziano's Latin poems, along with a history of Latin poetry from Petrarch to Poliziano. The work was designed to fill 480 pages and provide a detailed commentary and corresponding notes. By completing such a work as this, Johnson hoped to become known as a scholar-poet similar to Julius Caesar Scaliger, Daniel and Nikolaes Heinsius, Desiderius Erasmus, and Poliziano, all of whom Johnson admired.[73] Johnson began on 15 June 1743 and printed a Proposal for the work on 5 August 1734. However, the project did not receive enough funds and it was soon brought to an end.[74] Although the project failed, it shows that Johnson identified himself with neo-Latin humanism.[75]

Marriage

Johnson identified himself as a poet and, in November 1734, applied to Edward Cave to work on the poetry reviews for The Gentleman's Magazine.[75] In a letter written under the name S. Smith, Johnson said, "As You appear no less sensible than Your Readers of the defects of your Poetical Article, You will not be displeased, if, in order to the improvement of it, I communicate to You the sentiments of a person, who will undertake on reasonable terms sometimes to fill a column".[76] In particular, Johnson suggested removing the magazine's "low Jests" and "awkward Buffoonery" and then replacing them with poems, inscriptions, and "short literary Dissertations in Latin or English" written by himself.[76] Cave did not accept Johnson's proposal to write a column, but he did employ Johnson occasionally to work on minor aspects of the periodical.[75]

Around this time, Johnson became close to a man named Harry Porter, and remained with him during his terminal illness.[77] Porter died on 3 September 1734, leaving his wife Elizabeth Jervis Porter (otherwise known as "Tetty") widowed at the age of 45, with three children.[78] Months later, Johnson began to court the widow; Reverend William Shaw claims that "the first advances probably proceeded from her, as her attachment to Johnson was in opposition to the advice and desire of all her relations".[79] Johnson and Elizabeth became close, and they quickly fell in love. She admired Johnson greatly and claimed that he was "the most sensible man that I ever saw in my life".[75]

Johnson was inexperienced in relationships, but the well-to-do widow encouraged him and provided for him with her substantial savings.[80] The two were married on 9 July 1735, at St. Werburgh's Church in Derby.[81] The Porter family did not approve of the match, partly because Johnson was 25 and Elizabeth was 21 years his elder. His mother's marriage to Johnson so disgusted her son Jervis that he stopped talking to her.[82] Her other son Joseph later accepted the marriage, and her daughter, Lucy, accepted Johnson from the start.[83]

Edial Hall

During the previous June while working as a tutor for Thomas Whitby's children, Johnson had applied for the position of headmaster at Solihull School.[84] Walmesley lent his support to Johnson's application, but Johnson was passed over because the school's directors thought he was "a very haughty, ill-natured gent., and that he has such a way of distorting his face (which though he can't help) the gent[s] think it may affect some lads".[85] He was also rejected for a position at a school in Brewood for similar reasons.[86] Johnson did not give up his ambition to teach; with Walmesley's encouragement, he decided to set up his own school.[87]

In the autumn of 1735, Johnson opened a private academy at Edial, near Lichfield. The building, Edial Hall, was a large house with a pyramid-shaped roof and a unique design; a back room served as the schoolroom while the rest housed Johnson's family. He had only three pupils, David Garrick, George Garrick and Lawrence Offley; David Garrick—18 at the time—went on to become one of the most famous actors of his day.[85] Johnson designed a curriculum that focused on the reading of classical literature, starting with what he considered to be easier works, such as those by Corderius and Erasmus, before slowly progressing to Cornelius Nepos and finally onto Ovid, Vergil, and Horace. The school was advertised in the June and July 1736 editions of The Gentleman's Magazine: "At Edial, near Litchfield, in Staffordshire, Young Gentlemen are Boarded, and Taught the Latin and Greek Languages, by Samuel Johnson".[88]

After being open for little more than a year, the school failed in February 1737, gaining Johnson a reputation as a failed schoolmaster.[88] He slowly abandoned his desire to teach to focus more on writing his first major work, the historical tragedy Irene. The play did not earn him the money he had hoped for, though, until Garrick produced it in 1749.[89]

From Mr Garrick's account he did not appear to have been profoundly reverenced by his pupils. His oddities of manner, and uncouth gesticulations, could not but be the subject of merriment to them; and in particular, the young rogues used to listen at the door of his bed-chamber, and peep through the key-hole that they might turn into ridicule his tumultuous and awkward fondness for Mrs Johnson, whom he used to name by the familiar appellation of Tetty or Tetsey.[90]

On 2 March 1737, penniless, Johnson left for London with his former pupil David Garrick. To make things worse, Johnson received word that his brother had died on the day they left. However, their prospects were not completely hopeless, as Garrick was set to inherit a large sum the next year. Also, Garrick had connections in London, and the two would stay with his distant relative, Richard Norris, who lived on Exeter Street.[91] Johnson did not stay there long, and set out for Greenwich near the Golden Hart Tavern to finish Irene.[92] During that time, he wrote to Cave on 12 July 1737 and proposed a translation for Paolo Sarpi's The History of the Council of Trent (1619), which Cave did not accept until months later.[93]

Johnson started working on the translation of Sarpi before Cave approved, and he returned home to his wife during this time. In all, he managed to write between four hundred and eight hundred pages of text with corresponding commentary before he stopped working on it in April 1739.[94] In October 1737, Johnson brought his wife to London; they first lived at Woodstock Street and then moved to 6 Castle Street. Soon, Johnson found employment with Cave, and wrote for his The Gentleman's Magazine.[95] His work for the magazine and other publishers during this time "is almost unparalleled in range and variety", and "so numerous, so varied and scattered" that "Johnson himself could not make a complete list".[96]

In May 1738, his first major work, a poem called London, was published anonymously.[97] The work was based on Juvenal's Third Satire and describes the character Thales's leaving for Wales to escape the problems of London.[98] In particular, the poem describes how London is a place of crime, corruption, and the neglect of the poor. Johnson could not bring himself to regard the poem as granting him any merit as a poet;[99] however, Alexander Pope claimed that the author "will soon be déterré" (brought to light, become well known), although it did not immediately happen.[97]

In August, Johnson was denied a position as master of the Appleby Grammar School because a Master's degree from Oxford or Cambridge was required. To ensure that he would not suffer rejection again, Pope asked John Gower, a man with influence in the Appleby community, to have a degree awarded to Johnson.[6] Gower attempted to have a degree awarded to Johnson from Oxford, but he was told that it was "too much to be asked."[100] Gower then wrote to a friend of Jonathan Swift to persuade him to use his influence at the University of Dublin to have a masters awarded to Johnson, which could then be used to justify a masters awarded to Johnson from Oxford.[100] However, Swift refused to act on Johnson's behalf.[101] Regardless of Swift's motivation in not acting on Johnson's behalf, or how Johnson reacted to Swift's actions, it is known that Johnson then after refused to appreciate Swift as a poet, writer, or a satirist, with one exception: Swift's Tale of a Tub, of which Johnson doubted Swift's authorship.[102]

Between 1737 and 1739, Johnson became close to Richard Savage.[103] Feeling guilty for his own poverty, Johnson stopped living with his wife and spent time with Savage.[104] Together, they would roam the streets at night without enough money to stay in taverns or sleep in "night-cellars".[105] Savage was both a poet and a playwright, and Johnson was reported to enjoy spending time and discussing various topics with him, along with drinking and other merriment.[105] However, poverty eventually caught up with Savage, and Pope, along with Savage's other friends, gave him an "annual pension" in return for him agreeing to move to Wales. Savage ended up in Bristol however, and once again fell into debt by reliving his former London lifestyle. He was soon in debtors' prison and died in 1743.[106] A year later, Johnson wrote Life of Mr Richard Savage (1744) at Cave's prompting, and this work formed the beginning of Johnson's long-lasting success. The biography was a "moving" work that, according to Walter Jackson Bate, "remains one of the innovative works in the history of biography".[107]

Early works

Johnson's early works and early life have been neglected topics within Johnson scholarship. As a result, he is primarily known for the events surrounding his later life and later works like A Dictionary of the English Language. This imbalance originates in the failure of James Boswell, Johnson's friend and companion, to discuss in great detail Johnson's childhood and the beginning of his career within the Life of Samuel Johnson, the most famous biography on Johnson. In particular, Boswell ignored Johnson's early politics and political writings which show a concern with Sir Robert Walpole's political administration.[108]

His first major work, the poem London, contains an early version of Johnson's ethics and morality system. Within the poem, he combined attacks on the politics of Walpole and the British government with the immoral actions of the common Londoner to form a general satire of 18th-century London society.[109] Johnson compares London to the Roman Empire in its decline and blames moral and political corruption for its fall.[110] Although Johnson did not start his literary criticism career until later, London is an example of what Johnson thought poetry should be: it is youthful and joyous, but it also relies on simple language and easy to understand imagery.[111]

Johnson's first major success came with Life of Savage, but it was not his first biography; Savage was the fourth in a series which also included biographies of Jean-Philippe Baratier, Robert Blake and Francis Drake.[112] Although it was not the only biography that appeared immediately after Savage's death, it became the most popular, and it embodied Johnson's ideas on what a biography should be.[43]

The book did contain some inaccuracies, particularly those surrounding Savage's claim that he was the illegitimate child of a nobleman. It was successful in its partial analysis of Savage's poetry and in portraying insights into Savage's personality, but for all of its literary achievements it did not bring immediate fame or income to Johnson or to Cave;[113] it did, though, provide Johnson with a welcome small income at an opportune time in his life. More importantly, the work helped to mould Johnson into a biographical career; it was included in his later Lives of the Most Eminent English Poets series.[112]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Bate 1977, p. 5

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 10–13

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 12

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 13–14

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 15–16

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Watkins 1960, p. 25

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 16

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 18

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 19–20

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 20–21

- ↑ Boswell 1986, p. 38

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 18–19

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 21

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 25–26

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Lane 1975, p. 26

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Demaria 1994, pp. 5–6

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 19.2 Murray 1979

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Pearce 1994

- ↑ Stern, Burza & Robertson 2005

- ↑ Leckman et al. 2006

- ↑ Martin 2008, p. 94

- ↑ Zinner 2000

- ↑ Santangelo et al. 1994

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 29

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 31; Lane 1975, p. 27

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 23, 31

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 29

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 43

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 32

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Lane 1975, p. 30

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 350

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Lane 1975, p. 33

- ↑ Wain 1974, pp. 32–33

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 61

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 34

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Lane 1975, p. 34

- ↑ Lane 1975, pp. 34–36

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 38

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 UK CPI inflation numbers based on data available from Gregory Clark (2014), "What Were the British Earnings and Prices Then? (New Series)" MeasuringWorth.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Bate 1977, p. 87

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Lane 1975, p. 39

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 88

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 89

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Boswell 1986, p. 44

- ↑ Boswell 1986, p. 43

- ↑ Boswell 1969, p. 23

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 90–91

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 91–92

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 92

- ↑ Boswell 1986, p. 47

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 93–94

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 95

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 96

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 104–105

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 106–107

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Bate 1977, p. 127

- ↑ Wiltshire 1991, p. 24

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 128

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 Bate 1977, p. 129

- ↑ Watkins 1960, p. 56

- ↑ Warner 1802, p. 105

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 130–131

- ↑ Hopewell 1950, p. 53

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 131–132

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 132–134

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 134

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 136

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 137

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 137–138

- ↑ 72.0 72.1 Bate 1977, p. 138

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 Demaria 1994, p. 32

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 140–141

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 75.2 75.3 Demaria 1994, p. 33

- ↑ 76.0 76.1 Johnson 1992, p. 6

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 144

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 143

- ↑ Boswell 1969, p. 88

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 145

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 147

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 65

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 146

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 153–154

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 Bate 1977, p. 154

- ↑ Demaria 1994, p. 34

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 153

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Demaria 1994, p. 35

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 156

- ↑ Boswell 1986, p. 52

- ↑ Bate 1977, pp. 164–165

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 168–169

- ↑ Wain 1974, p. 81; Bate 1977, p. 169

- ↑ Demaria 1994, pp. 45–46

- ↑ Boswell 1986, pp. 169–170

- ↑ Bate 1955, p. 14

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 Lynch 2003, p. 5

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 172

- ↑ Bate 1955, p. 18

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Bate 1977, p. 182

- ↑ Watkins 1960, pp. 25–26

- ↑ Watkins 1960, pp. 26–27

- ↑ Watkins 1960, p. 51

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 178

- ↑ 105.0 105.1 Bate 1977, p. 179

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 181

- ↑ Bate 1977, p. 180

- ↑ Greene 2000, p. xxi

- ↑ Folkenflik 1997, p. 106

- ↑ Weinbrot 1997, p. 46

- ↑ Greene 1989, pp. 28, 35

- ↑ 112.0 112.1 Clingham 1997, p. 161

- ↑ Lane 1975, p. 100

References

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1955), The Achievement of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Oxford University Press, OCLC 355413.

- Bate, Walter Jackson (1977), Samuel Johnson, New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, ISBN 0-15-179260-7.

- Boswell, James (1969), Waingrow, Marshall, ed., Correspondence and Other Papers of James Boswell Relating to the Making of the Life of Johnson, New York: McGraw-Hill, OCLC 59269.

- Boswell, James (1986), Hibbert, Christopher, ed., The Life of Samuel Johnson, New York: Penguin Classics, ISBN 0-14-043116-0.

- Demaria, Robert (1994), The Life of Samuel Johnson, Oxford: Blackwell, ISBN 1-55786-664-3.

- Clingham, Greg (1997), "Life and literature in the Lives", in Clingham, Greg, The Cambridge companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 161–191, ISBN 0-521-55625-2

- Folkenflik, Robert (1997), "Johnson's politics", in Clingham, Greg, The Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 102–113, ISBN 0-521-55625-2.

- Greene, Donald (2000), "Introduction", in Greene, Donald, Political Writings, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, ISBN 0-86597-275-3.

- Greene, Donald (1989), Samuel Johnson: Updated Edition, Boston: Twayne Publishers, ISBN 0-8057-6962-5.

- Hopewell, Sydney (1950), The Book of Bosworth School, 1320–1920, Leicester: W. Thornley & Son, OCLC 6808364.

- Johnson, Samuel (1992), Redford, Bruce, ed., The Letters of Samuel Johnson, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-06881-X.

- Lane, Margaret (1975), Samuel Johnson & his World, New York: Harper & Row Publishers, ISBN 0-06-012496-2.

- Leckman, JF; Bloch, MH; King, RA; Scahill, L (2006), "Phenomenology of tics and natural history of tic disorders", Adv Neurol 99: 1–16, PMID 16536348.

- Lynch, Jack (2003), "Introduction to this Edition", in Lynch, Jack, Samuel Johnson's Dictionary, New York: Walker & Co, pp. 1–21, ISBN 0-8027-1421-8.

- Martin, Peter (2008), Samuel Johnson: A Biography, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Belknap Press, ISBN 978-0-674-03160-9.

- Murray, TJ (16 June 1979), "Dr Samuel Johnson's Movement Disorder", Br Med J 1 (6178): 1610–14, doi:10.1136/bmj.1.6178.1610, PMC 1599158, PMID 380753.

- Pearce, JMS (July 1994), "Doctor Samuel Johnson: 'the Great Convulsionary' a victim of Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome", J R Soc Med 87 (7): 396–9, PMC 1294650, PMID 8046726.

- Santangelo, SL; Pauls, DL; Goldstein, JM et al. (July–August 1994), "Tourette's syndrome: what are the influences of gender and comorbid obsessive-compulsive disorder?", J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 33 (6): 795–804, doi:10.1097/00004583-199407000-00004, PMID 8083136.

- Stern, JS; Burza, S; Robertson, MM (January 2005), "Gilles de la Tourette's syndrome and its impact in the UK", Postgrad Med J 81 (951): 12–9, doi:10.1136/pgmj.2004.023614, PMC 1743178, PMID 15640424,

It is now widely accepted that Dr Samuel Johnson had Tourette's syndrome

. - Wain, John (1974), Samuel Johnson, New York: Viking Press, OCLC 40318001.

- Warner, Richard (1802), A tour through the northern counties of England, and the borders of Scotland, Bath: R. Cruttwell, OCLC 945413.

- Watkins, W. B. C. (1960), Perilous Balance: The Tragic Genius of Swift, Johnson, and Sterne, Cambridge, MA: Walker-deBerry, Inc., OCLC 40318001.

- Weinbrot, Howard (1997), "Johnson's poetry", in Clingham, Greg, The Cambridge Companion to Samuel Johnson, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 34–53, ISBN 0-521-55625-2.

- Wiltshire, John (1991), Samuel Johnson in the Medical World, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-38326-9.

- Zinner, SH (2000), "Tourette disorder", Pediatr Rev 21 (11): 372–83, PMID 11077021.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||