Dybbuk

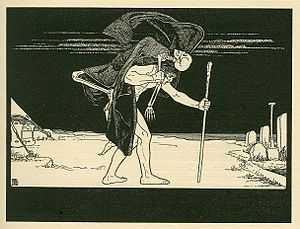

In Jewish mythology, a dybbuk (Yiddish: דיבוק, from Hebrew word meaning adhere or cling[1]) is a malicious possessing spirit believed to be the dislocated soul of a dead person.[2][3] It supposedly leaves the host body once it has accomplished its goal, sometimes after being helped.[3]

Etymology

"Dybbuk" is an abbreviation of dibbuk me-ru'aḥ ra'ah ("a cleavage of an evil spirit"), or dibbuk min ha-hiẓonim ("dibbuk from the outside"), which is found in man. "Dybbuk" comes from the Hebrew word "דיבוק," which means the act of sticking from the root "דבק," which means cling.

History

The term first appears in a number of 16th century writings,[1][4] though it was ignored by mainstream scholarship until S. Ansky's play The Dybbuk popularised the concept in literary circles.[4] Earlier accounts of possession (such as that given by Josephus) were of demonic possession rather than that by ghosts.[5] These accounts advocated orthodoxy among the populace[1] as a preventative measure. For example, it was suggested that a sloppily made mezuzah or entertaining doubt about Moses' crossing of the Red sea opened one's household to dybbuk possession. Very precise details of names and locations have been included in accounts of dybbuk possession. Rabbi Yoel Teitelbaum, the Satmar rebbe (1887–1979) is reported to have supposedly advised an individual said to be possessed to consult a psychiatrist.[5]

Ansky's play is a significant work of Yiddish theatre, and has been adapted a number of times by writers, composers and other creators including Jerome Robbins/Leonard Bernstein and Tony Kushner. In the play, a young bride is possessed by the ghost of the man she was meant to marry had her father not broken a marriage agreement.

There are other forms of soul transmigration in Jewish mythology. In contrast to the dybbuk, the ibbur (meaning "impregnation") is a positive possession, which happens when a righteous soul temporarily possesses a body. This is always done with consent, so that the soul can perform a mitzvah. The gilgul (Hebrew: גלגול הנשמות, literally "rolling") puts forth the idea that a soul must live through many lives before it gains the wisdom to rejoin with God.

In psychological literature the Dybbuk has been described as a hysterical syndrome.[6]

In popular culture

Film

Michał Waszyński's 1937 film The Dybbuk, based on the Yiddish play by S. Ansky, is considered one of the classics of Yiddish film-making.[7]

The dybbuk has been portrayed in popular culture in theatrical releases such as the films A Serious Man (2009), The Unborn (2009) and The Possession (2012).

In "Love and Death" (1975), a Woody Allen satire on Russian Literature, Boris (Woody) is flirting with Sonja (Diane Keaton) who is with a fish monger she is set to marry. As the fish monger keeps getting in the way, Boris asks Sonja, "Did you have to bring the dybbuk"

In Romain Gary's 1967 novel The Dance of Genghis Cohn, a concentration camp commander is haunted by the dybbuk of one of his victims. [8]

In Ellen Galford's 1993 novel The Dyke and the Dybbuk, lesbian taxi-driver Rainbow Rosenbloom is haunted by, and gets the better of, a female dybbuk haunting her as a result of a curse placed on her ancestor 200 years ago.[5]

The dybbuk appears in written fiction in The Inquisitor's Apprentice (2011), a novel by Chris Moriarty.

In the comic series Girl Genius, the forcible insertion of the mind of Agatha's mother, the main villain Lucrezia Mongfish/"The Other", into her own was compared to a dybbuk by one of her followers when reporting the situation to someone else.

Television

The Dybbuk is mentioned in a scary story told by Boris Kropotkin in the Rugrats episodes "Monster in the Garage" and "Toys in the Attic".

See also

Further reading

- J.H. Chajes, Between Worlds: Dybbuks, Exorcists, and Early Modern Judaism, University of Pennsylvania Press, Aug 31, 2011.

- Rachel Elior, Dybbuks and Jewish Women in Social History, Mysticism and Folklore, Urim Publications, 1 Sep 2008.

- Fernando Peñalosa, The Dybbuk: Text, Subtext, and Context. Jan 2013.

- Fernando Peñalosa. Parodies of An-sky’s The Dybbuk. Nov 2012

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews, by Avner Falk, p.538, Fairleigh Dickinson Univ Press, 1996

- ↑ "Dybbuk", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, retrieved 2009-06-10

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Dibbuk", Encyclopedia Judaica, by Gershom Scholem.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Spirit Possession in Judaism: Cases and Contexts from the Middle Ages to the Present, by Matt Goldish, p.41, Wayne State University Press, 2003

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Tree of Souls:The Mythology of Judaism, by Howard Schwartz, pp. 229–230, Oxford University Press, 1 Nov 2004

- ↑ Billu, Y; Beit-Hallahmi, B. (1989). "Dybbuk-Possession as a hysterical symptom: Psychodynamic and socio-cultural factors". Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Science 26: 138-149.

- ↑ "The Dybbuk". The National Center for Jewish Film. Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ Schwartz, Howard (1998). Reimagining the Bible: The Storytelling of the Rabbis. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195104998.

External links

- "The Dybbuk" by Ansky Jewish Heritage Online Magazine

- Spiritual Possession and Jewish Folklore

- Encyclopedia Britannica