Dutch language

| Dutch | |

|---|---|

| Flemish | |

| Nederlands, Vlaams | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈneːdərlɑnts] |

| Native to | Mainly the Netherlands, Belgium, and Suriname; also in Aruba, Curaçao, Sint Maarten, as well as France (French Flanders). |

| Region | mainly Western Europe, today also in Africa, South America and the Caribbean. |

Native speakers |

22 million (2012)[1] 28 million (L1 plus L2 speakers) (2012)[2][3] |

Early forms |

Old Dutch

|

|

Latin (Dutch alphabet) Dutch Braille | |

| Signed Dutch (Nederlands met Gebaren) | |

| Official status | |

Official language in |

|

| Regulated by |

Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-1 |

nl |

| ISO 639-2 |

dut (B) nld (T) |

| ISO 639-3 |

Variously: nld – Dutch/Flemish vls – West Flemish (Vlaams) zea – Zealandic (Zeeuws) |

| Glottolog |

mode1257[4] |

| Linguasphere |

52-ACB-a (varieties: |

|

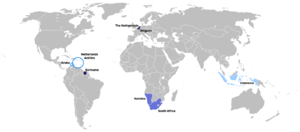

Dutch-speaking world (included are areas of daughter-language Afrikaans). | |

|

Distribution of the Dutch language and its dialects in Western Europe | |

Dutch (![]() Nederlands ) is a West Germanic language and the native language of most of the population of the Netherlands, and about sixty percent of the populations of Belgium and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second language for another 5 million people.[2][3][5][6]

Nederlands ) is a West Germanic language and the native language of most of the population of the Netherlands, and about sixty percent of the populations of Belgium and Suriname, the three member states of the Dutch Language Union. Most speakers live in the European Union, where it is a first language for about 23 million and a second language for another 5 million people.[2][3][5][6]

Dutch also holds official status in the Caribbean island nations of Aruba, Curaçao and Saint Maarten, whereas Dutch or dialects assigned to it continue to be spoken in parts of France and Germany, and to a lesser extent, in Indonesia,[n 1] and up to half a million native Dutch speakers may be living in the United States, Canada, and Australia.[n 2] The Cape Dutch dialects of Southern Africa have been standardised into Afrikaans, a partially mutually intelligible daughter language[n 3] which today is spoken by an estimated total of 15 to 23 million people in South Africa and Namibia.[n 4]

Dutch is closely related to German and English[n 5] and is said to be roughly in between them.[n 6] Dutch shares with German a similar word order, grammatical gender, and a largely Germanic vocabulary; it has however—like English—not undergone the High German consonant shift, does not use Germanic umlaut as a grammatical marker, and has levelled much of its morphology, including the case system.[n 7] Dutch has three grammatical genders,[7] but this distinction has fewer grammatical consequences than in German.[n 8] Dutch also shares with German the use of modal particles,[8] [9] final-obstruent devoicing, and the use of subject–verb–object word order in main clauses and subject–object–verb in subordinate clauses[n 9]. The view about mutual intelligibility between Dutch and German varies.[10][11][12] Dutch vocabulary is mostly Germanic and contains the same Germanic core as German and English, incorporating more Romance loans than German and fewer than English.[n 10]

Names

While "Dutch" generally refers to the language as a whole, Belgian varieties are sometimes collectively referred to as "Flemish". In both Belgium and the Netherlands, the native official name for Dutch is Nederlands, and its dialects have their own names, e.g. Hollands "Hollandish", West-Vlaams "Western Flemish", Brabants "Brabantian".[13]

The language has been known under a variety of names. In Middle Dutch, dietsc (in the South) and diutsc, duutsc (in the North) were used to refer variably to Dutch, Low German, and German. This word is derived from diet "people" and was used to translate Latin (lingua) vulgaris "popular language" to set apart the Germanic vernacular from Latin (the language of writing and the Church) and Romance.[14] An early form of this word appears Latinized in the Strasbourg Oaths (AD 842) as teudisca (lingua) to refer to the Rhenish Franconian portion of the oath and also underlies dialectal French thiois "Luxembourgish", "Lorraine Franconian", and which has survived in Italian as tedesco, "German".

During the Renaissance in the 16th century, duytsch (modern Duits) "German" and nederduytsch "Low German" began to be differentiated from dietsch or nederlandsch "Dutch",[15] a distinction that is echoed in English later the same century with the terms High Dutch "German" and Low Dutch "Dutch". However, owing to Dutch commercial and colonial rivalry in the 16th and 17th centuries, the English term came to refer exclusively to the Dutch. In modern Dutch, Duits has narrowed in meaning to refer to "German", Diets went out of common use because of its Nazi associations[16] and now somewhat romantically refers to older forms of Dutch,[17] whereas Vlaams is sometimes used to name the language as a whole for the varieties spoken in Belgium.[18]

Nederlands, the official Dutch word for "Dutch", did not become firmly established until the 19th century. The repeated use of neder- or "low" to refer to the language is a reference to the Netherlands' downriver location at the mouth of the Rhine (harking back to Latin nomenclature, e.g. Germania inferior vs. Germania superior) and its position at the lowest dip of the Northern European plain.[19][20][21]

Classification

Dutch belongs to its own West Germanic sub-group, West Low Franconian, paired with its sister language Limburgish, or East Low Franconian, both of which stand out by mixing characteristics of Low German and High German.[22] Dutch is at one end of a dialect continuum known as the Rhenish fan where German gradually turns into Dutch. Dutch is also at one end of a dialect continuum with Low German, but these dialects however are gradually becoming extinct.

All three languages have shifted earlier /θ/ > /d/, show final-obstruent devoicing (Du brood "bread" [broːt]), and experienced lengthening of short vowels in stressed open syllables which has led to contrastive vowel length that is used as a morphological marker. Dutch stands out from Low German and High German in its retention of the clusters /sp/ and /st/, while shifting of /sk/ to /sx/. It also did not develop i-mutation as a morphological marker, although some eastern dialects did. In earlier periods, Low Franconian of either sort differed from Low German by maintaining a three-way plural verb conjugation (Old Dutch -un, -it, -unt → Middle Dutch -en, -t, -en).

In modern Dutch, the former 2nd-person plural (-t) took the place of the 2nd-person singular, and the plural endings were reduced into a single form -en (cf. Du jij maakt "you(sg) make" vs. wij/jullie/zij maken "we/you(pl)/they make"). However, it is still possible to distinguish it from German (which has retained the three-way split) and Low German (which has -t in the present tense: wi/ji/se niemmet "we/you(pl)/they take"). Dutch and Low German show the collapsing of older ol/ul/al + dental into ol + dental, but in Dutch wherever /l/ was pre-consonantal and after a short vowel, it vocalized, e.g., Du goud "gold", zout "salt", woud "woods" : LG Gold, Solt, Woold : Germ Gold, Salz, Wald.

With Low German, Dutch shares:

- The development of /xs/ > /ss/ (Du vossen "foxes", ossen "oxen", LG Vösse, Ossen vs. Germ Füchse, Ochsen)

- /ft/ → /xt/ though it is far more common in Dutch (Du zacht "soft", LG sacht vs. Germ sanft, but Du lucht "air" vs. LG/Germ Luft)

- Generalizing the dative over the accusative case for certain pronouns (Du mij "me" (MDu di "you (sg.)"), LG mi/di vs. Germ mich/dich)

- Lack of the second consonant shift

- Monophthongization of Germanic *ai > ē and *au > ō, e.g., Du steen "stone", oog "eye", LG Steen, Oog vs. G Stein, Auge, although this is not true of Limburgish (cf. sjtein, oug). Exceptions include klein "small" and geit "goat" (but West Flemish kleene, geet).

- Loss of Germanic -z (which later became -r) in monosyllabic words. For example, the German pronoun wir "we" corresponds to Du wij (but Limburgish veer), LG wi.

With German (but not with Low German), Dutch shares:

- The reflexive pronoun zich (Germ sich). This was originally borrowed from Limburgian, which is why in most dialects (Flemish, Brabantine) the usual reflexive is hem/haar or z'n eigen, just like in the rest of West Germanic.

- Diphthongization of Germanic ē² > ie > i and ō > uo > u (Du hier "here", voet "foot", Germ hier, Fuß (from earlier fuoz) vs. LG hier [iː], Foot [oː])

- Voicing of pre-vocalic initial voiceless alveolar fricatives, e.g., Du zeven "seven", Germ sieben [z] vs. LG söven, seven [s].

- Final-obstruent devoicing

Diachronic

The table below shows the succession of the significant historical stages of each language (horizontally) and their approximate groupings in subfamilies (vertically). Vertical sequence within each group does not imply a measure of greater or lesser similarity.

- ^1 There are conflicting opinions on the classification of Lombardic. It has also been classified as close to Old Saxon.

- ^2 Late Middle Ages refers to the post-Black Death period. Especially for the language situation in Norway this event was important.

- ^3 From Early Northern Middle English.[23] McClure gives Northumbrian Old English.[24] In the Oxford Companion to the English Language (p. 894) the 'sources' of Scots are described as "the Old English of the Kingdom of Bernicia" and "the Scandinavian-influenced English of immigrants from Northern and Midland England in the 12-13c [...]." The historical stages 'Early—Middle—Modern Scots' are used, for example, in the "Concise Scots Dictionary"[25] and "A Dictionary of the Older Scottish Tongue".[26]

- ^4 The speakers of Norn were assimilated to speak Modern Scots varieties (Insular Scots).

- ^5 Modern Gutnish (Gutamål), the direct descendant of Old Gutnish (Gutniska), has been marginalized by the Gotlandic dialect/accent of Standard Swedish (Gotländska).

- ^6 Mainland Old Norwegian existed along a dialect continuum between West and East Old Norse.

Geographic distribution

| Country | Speakers | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Netherlands[n 11] | 15,700,000[27] | 2012 |

| Belgium | 5,660,000[27] | 2012 |

| Suriname | 200,000[27] | 1997 |

| Caribbean Netherlands | 20,900[27] | N/A |

| Curaçao | 11,400[27] | 2011 |

| Aruba | 5,290[27] | N/A |

| Sint Maarten | 2,000[27] | 2011 |

| Total worldwide | 21,944,690[27] | N/A |

Dutch is an official language of the Netherlands, Belgium, Suriname, Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten. Dutch is also an official language of several international organisations, such as the European Union, Union of South American Nations [28] and the Caribbean Community.

Europe

Netherlands

Dutch is the official and foremost language of the Netherlands, a nation of 16.7 million people of whom 96 percent speak Dutch as their mother tongue.[29] In the province of Friesland and a small part of Groningen, Frisian is also recognised and is spoken by a few hundred thousand Frisians. In the Netherlands there are many different dialects, but these are often overruled and replaced by the language of the media, school, government (i.e., Standard Dutch).

Immigrant languages are Indonesian, Turkish, German, Berber, Moroccan Arabic, English, Spanish, Papiamento, and Sranan. In the second generation these newcomers often speak Dutch as their mother tongue, sometimes alongside the language of their parents.

Belgium

Belgium, a nation of 11 million people, has three official languages, which are, in order from the largest speaker population to the smallest, Dutch (sometimes colloquially referred to as Flemish), French, and German. An estimated 59% of all Belgians speak Dutch as their first language, while French is the mother tongue of 40%.[30]

Dutch is the official language of the Flemish Region (where it is the mother tongue of about 97% of the population)[29] and one of the two official languages—along with French—of the Brussels Capital Region. Dutch is not official nor a recognised minority language in the Walloon Region, although on the border with the Flemish Region, there are four municipalities with language facilities for Dutch speakers. The most important Dutch dialects spoken in Belgium are West Flemish (also spoken in French Flanders), East Flemish, Brabantian, and Limburgish, the latter having a dialect continuum in northeastern Wallonia and adjacent areas of Germany (as Low Dietsch).

Brussels

.svg.png)

Since the founding of the Kingdom of Belgium in 1830, its capital Brussels has transformed from being almost entirely Dutch-speaking, with a small French minority, to being a multilingual city with French as the majority language and lingua franca. This language shift, the Frenchification of Brussels, is rooted in the 18th century but accelerated after Belgium became independent and Brussels expanded past its original boundaries.[32][33]

Not only is French-speaking immigration responsible for the frenchification of Brussels, but more importantly the language change over several generations from Dutch to French was performed in Brussels by the Flemish people themselves. The main reason for this was the low social prestige of the Dutch language in Belgium at the time.[34] From 1880 on more and more Dutch-speaking people became bilingual resulting in a rise of monolingual French speakers after 1910. Halfway through the 20th century the number of monolingual French speakers carried the day over the (mostly) bilingual Flemish inhabitants.[35]

Only since the 1960s, after the fixation of the Belgian language border and the socio-economic development of Flanders was in full effect, could Dutch stem the tide of increasing French use.[36] This phenomenon is, together with the future of Brussels, one of the most controversial topics in all of Belgian politics.[37][38]

Today an estimated 16 percent of city residents are native speakers of Dutch, while an additional 13 percent claim to have a "good to excellent" knowledge of Dutch.[31]

France

French Flemish, a variant of West Flemish, is spoken in the north-east of France by an estimated population of 20,000 daily speakers and 40,000 occasional speakers. It is spoken alongside French, which is gradually replacing it for all purposes and in all areas of communication.[39] Neither Dutch nor its regional French Flemish variant is afforded legal status in France, either by the central or regional public authorities, by the education system or before the courts. In brief, the state takes no measures to ensure the use of Dutch in France.[39]

In the 9th century the Germanic–Romance language border went from the mouth of the Canche to just north of the city of Lille, where it coincided with the present language border in Belgium.[40] From the late 9th century on, the border gradually started to shift northward and eastward to the detriment of the Germanic language.[40]

Boulogne-sur-Mer was bilingual up to the 12th century, Calais up to the 16th century, and Saint-Omer until the 18th century. The western part of the County of Flanders, consisting of the castellanies of Bourbourg, Bergues, Cassel and Bailleul, became part of France between 1659 and 1678. However, the linguistic situation in this formerly monolingually Dutch-speaking region did not dramatically change until the French Revolution in 1789, and Dutch continued to fulfil the main functions of a cultural language throughout the 18th century.[40]

During the 19th century, especially in the second half of it, Dutch was banned from all levels of education and lost most of its functions as a cultural language. The cities of Dunkirk, Gravelines and Bourbourg had become predominantly French-speaking by the end of the 19th century. In the countryside, until World War I, many elementary schools continued to teach in Dutch, and the Roman Catholic Church continued to preach and teach the cathechism in Flemish in many parishes.[40]

Nonetheless, since French enjoyed a much higher status than Dutch, from about the interbellum onward everybody became bilingual, the generation born after World War II being raised exclusively in French. In the countryside, the passing on of Flemish stopped during the 1930s or 1940s. As a consequence, the vast majority of those still having an active command of Flemish belong to the generation of over the age of 60.[40] Therefore, complete extinction of French Flemish can be expected in the coming decades.[40]

Asia

Despite the Dutch presence in Indonesia for almost 350 years, the Dutch language has no official status there[42] and the small minority that can speak the language fluently are either educated members of the oldest generation, or employed in the legal profession,[43] as some legal codes are still only available in Dutch.[44] Many universities include Dutch as a source language, mainly for law and history students (roughly 35,000 of them nationally).[45][46]

Unlike other European nations, the Dutch chose not to follow a policy of language expansion amongst the indigenous peoples of their colonies.[47] In the last quarter of the 19th century, however, a local elite gained proficiency in Dutch so as to meet the needs of expanding bureaucracy and business.[48] Nevertheless, the Dutch government remained reluctant to teach Dutch on a large scale for fear of destabilising the colony. Dutch, the language of power, was supposed to remain in the hands of the leading elite.[48]

Instead, use of local languages—or, where this proved to be impractical, of Malay—was encouraged. As a result, fewer than 2% of Indonesians could speak Dutch in 1940.[48] Only when in 1928 the Indonesian nationalist movement had chosen Malay as a weapon against Dutch influence, the colonial authorities gradually began to introduce Dutch into the educational curriculum. But because of the chaos of the 1942 Japanese invasion and the subsequent Indonesian independence in 1945, this shift in policy did not come into full effect.[48]

After independence, Dutch was dropped as an official language and replaced by Malay. Yet the Indonesian language inherited many words from Dutch: words for everyday life as well as scientific and technological terms.[49] One scholar argues that 20% of Indonesian words can be traced back to Dutch words,[50] many of which are transliterated to reflect phonetic pronunciation e.g. kantoor (Dutch for "office") in Indonesian is kantor, while bus ("bus") becomes bis.

In addition, many Indonesian words are calques on Dutch, for example, rumah sakit (Indonesian for "hospital") is calqued on the Dutch ziekenhuis (literally "sick house"), kebun binatang ("zoo") on dierentuin (literally "animal garden"), undang-undang dasar ("constitution") from grondwet (literally "basic law"). These account for some of the differences in vocabulary between Indonesian and Malay.

The first spelling system for Indonesian, devised by Charles van Ophuijsen[50] was influenced by Dutch, with the use of Dutch letter combinations such as oe. For example, tempo doeloe (meaning "the past") was pronounced as "dulu". In 1947, this was changed to u, hence tempo dulu. However, the letter combination oe continued to be used in people's names, e.g. the first two Presidents of Indonesia, Sukarno and Suharto, are often written as Soekarno and Soeharto. In 1972, following an agreement with Malaysia to harmonise the spelling of Indonesian and Malay, other Dutch-influenced letter combinations were replaced, e.g. tj and dj became c and j, respectively. For instance tjap ("brand" in Indonesian) became cap and Djakarta, the country's capital, became Jakarta.

Dutch-based creole languages spoken (now or formerly) in the Dutch East Indies include Javindo and Petjo, most of whose speakers were Indo or Eurasians. As a result of Indo emigration to the Netherlands following independence, the use of these languages declined.

The century and half of Dutch rule in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and southern India left few traces of the Dutch language. A few words such as tapal, kokin and kakhuis are still used in some of the Indian languages.

Oceania

After the declaration of independence of Indonesia, Western New Guinea remained a Dutch colony until 1962, known as Netherlands New Guinea.[51] Despite prolonged Dutch presence, the Dutch language is not spoken by many Papuans, the colony having been ceded to Indonesia in 1963.

Immigrant communities can be found in Australia and New Zealand. The 2006 Australian census showed 36,179 people speaking Dutch at home.[52] At the 2006 New Zealand Census, 26,982 people, or 0.70 percent of the total population, reported to speak Dutch to sufficient fluency that they could hold an everyday conversation.[53]

Americas

In contrast to the colonies in the East Indies, from the second half of the 19th century onwards, the Netherlands envisaged expansion of Dutch in its colonies in the West Indies. Until 1863, when slavery was abolished in the West Indies, slaves were forbidden to speak Dutch. Most important were the efforts of Christianisation through Dutchification, which did not occur in Indonesia owing to a policy of non-involvement in the Islamised regions. Secondly, most of the people in the Colony of Surinam (now Suriname) worked on Dutch plantations, which reinforced the importance of Dutch as a means for direct communication.[48][54] In Indonesia, the colonial authorities had less interference in economic life. The size of the population was decisive: whereas the Antilles and Surinam combined only had a few hundred thousand inhabitants, Indonesia had many millions, by far outnumbering the population of the Netherlands.[48]

Suriname

In Suriname, where in the second half of the 19th century the Dutch authorities introduced a policy of assimilation,[48] Dutch is the sole official language[55] and over 60 percent of the population speaks it as a mother tongue.[5] A further twenty-four percent of the population speaks Dutch as a second language.[56] Suriname gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1975 and has been an associate member of the Dutch Language Union since 2004.[57] The lingua franca of Suriname, however, is Sranan Tongo,[58] spoken natively by about a fifth of the population.[29][59]

Caribbean

In Aruba, Curaçao and Sint Maarten, all parts of the Kingdom of the Netherlands, Dutch is the official language but spoken as a first language by only 7% to 8% of the population,[60] although most native-born people on the islands can speak the language since the education system is in Dutch at some or all levels.[61] The lingua franca of Aruba, Bonaire and Curaçao is Papiamento, a creole language that originally developed among the slave population. The population of the three northern Antilles, Sint Maarten, Saba, and Sint Eustatius, is predominantly English-speaking.[48]

North America

In New Jersey in the United States, an almost extinct dialect of Dutch, Jersey Dutch, spoken by descendants of 17th-century Dutch settlers in Bergen and Passaic counties, was still spoken as late as 1921.[62] Other Dutch-based creole languages once spoken in the Americas include Mohawk Dutch (in Albany, New York), Berbice (in Guyana), Skepi (in Essequibo, Guyana) and Negerhollands (in the United States Virgin Islands). Pennsylvania Dutch is not a member of the set of Dutch dialects and is less misleadingly called Pennsylvania German.[63]

Martin Van Buren, the eighth President of the United States, spoke Dutch as his first language and is the only U.S. President to have spoken a language other than English as his first language. Dutch prevailed for many generations as the dominant language in parts of New York along the Hudson River. Another famous American born in this region who spoke Dutch as a first language was Sojourner Truth.

According to the 2000 United States census, 150,396 people spoke Dutch at home,[64] while according to the 2006 Canadian census, this number reaches 160,000 Dutch speakers.[65] In Canada, Dutch is the fourth most spoken language by farmers, after English, French and German,[66] and the fifth most spoken non-official language overall (by 0.6% of Canadians).[67]

Africa

Belgian Africa

Belgium, which had gained its independence from the Netherlands in 1830, also held a colonial empire from 1901 to 1962, consisting of the Belgian Congo and Ruanda-Urundi. Unlike Belgium itself, the colonies had no de jure official language.[68][69] Although a majority of Belgians residing in the colonies were Dutch-speaking,[68] French was de facto the sole language used in administration, jurisdiction and secondary education.[70]

After World War II, proposals of dividing the colony into a French-speaking and a Dutch-speaking part—after the example of Belgium—were discussed within the Flemish Movement.[70][71] In general, however, the Flemish Movement was not as strong in the colonies as in the mother country.[72] Although in 1956, on the eve of Congolese independence, an estimated 50,000 out of a total of 80,000 Belgian nationals would have been Flemish,[68] only 1,305 out of 21,370 children were enrolled in Dutch-language education.[73]

When the call for a better recognition of Dutch in the colony got louder, the évolués ("developed Congolese")—among them Mobutu Sese Seko—argued that Dutch had no right over the indigenous languages, defending the privileged position of French.[68][73] Moreover, the image of Afrikaans as the language of the apartheid was injurious to the popularity of Dutch.[73]

The colonial authorities used Lingala, Kongo, Swahili and Tshiluba in communication with the local population and in education.[70] In Ruanda-Urundi this was Kirundi.[74] Knowledge of French—or, to an even lesser extent, Dutch—was hardly passed on to the natives,[68] of whom only a small number were taught French to work in local public services.[48] After their independence, French would become an official language of the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda and Burundi.[74] Of these, Congo is the most francophone country. Knowledge of Dutch in former Belgian Africa is almost nonexistent, except for the people who have learned the language while living or being emigrants in Belgium.

Afrikaans

|

0–20%

20–40%

40–60% |

60–80%

80–100% |

|

<1 /km²

1–3 /km²

3–10 /km²

10–30 /km²

30–100 /km² |

100–300 /km²

300–1000 /km²

1000–3000 /km²

>3000 /km² |

The largest legacy of the Dutch language lies in South Africa, which attracted large numbers of Dutch, Flemish and other northwest European farmer (in Dutch, boer) settlers, all of whom were quickly assimilated.[75] The long isolation from the rest of the Dutch-speaking world made the Dutch as spoken in Southern Africa evolve into what was then Afrikaans.[76] In 1876, the first Afrikaans newspaper called Die Afrikaanse Patriot was published in the Cape Colony.[77]

European Dutch remained the literary language[76] until the start of the 1920s, when under pressure of Afrikaner nationalism the local "African" Dutch was preferred over the written, European-based standard.[75] In 1925, section 137 of the 1909 constitution of the Union of South Africa was amended by Act 8 of 1925, stating "the word Dutch in article 137 [...] is hereby declared to include Afrikaans".[78][79] The constitution of 1983 only listed English and Afrikaans as official languages. It is estimated that between 90% to 95% of Afrikaans vocabulary is ultimately of Dutch origin.[80][81]

Both languages are still largely mutually intelligible, although this relation can in some fields (such as lexicon, spelling and grammar) be asymmetric, as it is easier for Dutch speakers to understand written Afrikaans than it is for Afrikaans speakers to understand written Dutch.[82] Afrikaans is grammatically far less complex than Dutch, and vocabulary items are generally altered in a clearly patterned manner, e.g. vogel becomes voël ("bird") and regen becomes reën ("rain").[83]

It is the third language of South Africa in terms of native speakers (~13.5%),[84] of whom 53 percent are Coloureds and 42.4 percent Whites.[85] In 1996, 40 percent of South Africans reported to know Afrikaans at least at a very basic level of communication.[86] It is the lingua franca in Namibia,[75][87][88] where it is spoken natively in 11 percent of households.[89] In total, Afrikaans is the first language in South Africa alone of about 6.8 million people[84] and is estimated to be a second language for at least 10 million people worldwide,[90] compared to over 23 million[5] and 5 million respectively, for Dutch.[2]

History

The history of the Dutch language begins around AD 450–500 after Old Frankish, one of the many West Germanic tribal languages, was split by the Second Germanic consonant shift. At more or less the same time the Ingvaeonic nasal spirant law led to the development of the direct ancestors of modern Dutch Low Saxon, Frisian and English. The northern dialects of Old Frankish generally did not participate in either of these two shifts, except for a small amount of phonetic changes, and are hence known as Old Low Franconian; the "Low" refers to dialects not influenced by the consonant shift.

The most south-eastern dialects of the Franconian languages became part of High—though not Upper—German even though a dialect continuum remained. The fact that Dutch did not undergo the sound changes may be the reason why some people say that Dutch is like a bridge between English and German. Within Old Low Franconian there were two subgroups: Old East Low Franconian and Old West Low Franconian, which is better known as Old Dutch.

Old Dutch

Old Dutch is the language ancestral to the Low Franconian languages, including Dutch itself. It was spoken between the 6th and 11th centuries, continuing the earlier Old Frankish language.

The present Dutch standard language is derived from Old Dutch dialects spoken in the Low Countries that were first recorded in the Salic law, a Frankish document written around 510. From this document originated the oldest sentence that has been identified as Dutch: "Maltho thi afrio lito" as sentence used to free a serf. Other old segments of Dutch are "Visc flot aftar themo uuatare" ("A fish was swimming in the water") and "Gelobistu in got alamehtigan fadaer" ("Do you believe in God the almighty father"). The latter fragment was written around 900.

Arguably the most famous text containing "Old Dutch" is: "Hebban olla vogala nestas hagunnan, hinase hic enda tu, wat unbidan we nu" ("All birds have started making nests, except me and you, what are we waiting for"), dating around the year 1100, written by a Flemish monk in a convent in Rochester, England.

The oldest known single word is vadam (modern Dutch wad, English: mudflat), from the year 107 CE.

East Low Franconian was eventually absorbed by Dutch as it became the dominant form of Low Franconian, although it remains a noticeable substrate within the southern Limburgish dialects of Dutch. As the two groups were so similar, it is often difficult to determine whether a text is Old Dutch or Old East Low Franconian; hence most linguists will generally use Old Dutch synonymously with Old Low Franconian and mostly do not differentiate.

Development phases

Dutch, like other Germanic languages, is conventionally divided into three development phases which were:

- 450(500)–1150 Old Dutch (First attested in the Salic Law)

- 1150–1500 Middle Dutch (Also called "Diets" in popular use, though not by linguists)

- 1500–present Modern Dutch (Saw the creation of the Dutch standard language and includes contemporary Dutch)

The transition between these languages was very gradual and one of the few moments linguists can detect somewhat of a revolution is when the Dutch standard language emerged and quickly established itself. Standard Dutch is very similar to most Dutch dialects.

The development of the Dutch language is illustrated by the following sentence in Old, Middle and Modern Dutch:

- "Irlôsin sol an frithe sêla mîna fan thên thia ginâcont mi, wanda under managon he was mit mi" (Old Dutch)

- "Erlossen sal [hi] in vrede siele mine van dien die genaken mi, want onder menegen hi was met mi" (Middle Dutch)

(Using same word order)

- "Verlossen zal hij in vrede ziel mijn van degenen die [te] na komen mij, want onder menigen hij was met mij" (Modern Dutch)

(Using correct contemporary Dutch word order, without inversion )

- "Hij zal mijn ziel in vrede verlossen van degenen die mij te na komen, want onder menigen was hij met mij" (Modern Dutch) (see Psalm 55:19)

- "He shall my soul in peace free from those who me too near come, because amongst many was he with me" (English literal translation in the same word order)

- "He will deliver my soul in peace from those who attack me, because, amongst many, he was with me" (English translation in unmarked word order) (see Psalm 55:18)

A process of standardisation started in the Middle Ages, especially under the influence of the Burgundian Ducal Court in Dijon (Brussels after 1477). The dialects of Flanders and Brabant were the most influential around this time. The process of standardisation became much stronger at the start of the 16th century, mainly based on the urban dialect of Antwerp. In 1585 Antwerp fell to the Spanish army: many fled to the Northern Netherlands, especially the province of Holland, where they influenced the urban dialects of that province. In 1637, a further important step was made towards a unified language,[91] when the Statenvertaling, the first major Bible translation into Dutch, was created that people from all over the United Provinces could understand. It used elements from various, even Dutch Low Saxon, dialects but was predominantly based on the urban dialects of Holland of post 16th century which in turn were heavily influenced by the 16th century dialects of Brabant. Brabantian has had a large influence on the development of Standard Dutch. This was because of Brabant was being the dominant region in the Netherlands when standardization of the Dutch started in the 16th century. The first major formation of standard Dutch also took place in Antwerp, where a Brabantian dialect is spoken.[92]

Dialects

Dutch dialects are primarily the dialects that are both cognate with the Dutch language and are spoken in the same language area as the Dutch standard language. Dutch dialects are remarkably diverse and are found in the Netherlands and northern Belgium.

The province of Friesland is bilingual. The West Frisian language, distinct from Dutch, is spoken here along with standard Dutch and the Stadsfries dialect. A (West) Frisian standard language has also been developed.

First dichotomy

In the east there is an extensive Dutch Low Saxon dialect area: the provinces of Groningen (Gronings), Drenthe and Overijssel are almost exclusively Low Saxon, and a major part of the province of Gelderland also belongs to it. The IJssel river roughly forms the linguistic watershed here. This group, though not being Low Franconian and being very close to neighbouring Low German, is still regarded as Dutch, because of the superordination of the Dutch standard language in this area ever since the seventeenth century; in other words, this group is Dutch synchronically but not diachronically.

Extension across the borders

- Gronings, spoken in Groningen (Netherlands), as well as the closely related varieties in adjacent East Frisia (Germany), has been influenced by the Frisian language and takes a special position within the Low Saxon Language.

- South Guelderish (Zuid-Gelders) is a dialect spoken in Gelderland (Netherlands) and in adjacent parts of North Rhine-Westphalia (Germany).

- Brabantian (Brabants) is a dialect spoken in Antwerp, Flemish Brabant (Belgium) and North Brabant (Netherlands).

- Limburgish (Limburgs) is spoken in Limburg (Belgium) as well as in Limburg (Netherlands) and extends across the German border.

- West Flemish (Westvlaams) is spoken in West Flanders (Belgium), the western part of Zeelandic Flanders (Netherlands) and historically also in French Flanders (France).

- East Flemish (Oostvlaams) is spoken in East Flanders (Belgium) and the eastern part of Zeelandic Flanders (Netherlands).

Holland and the Randstad

In Holland, Hollandic is spoken, though the original forms of this dialect (which were heavily influenced by a Frisian substratum and, from the 16th century on, by Brabantian dialects) are now relatively rare. The urban dialects of the Randstad, which are Hollandic dialects, do not diverge from standard Dutch very much, but there is a clear difference between the city dialects of Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam or Utrecht.

In some rural Hollandic areas more authentic Hollandic dialects are still being used, especially north of Amsterdam. Another group of dialects based on Hollandic is that spoken in the cities and larger towns of Friesland, where it partially displaced West Frisian in the 16th century and is known as Stadsfries ("Urban Frisian").

Minority languages

Limburgish has the status of official regional language (or streektaal) in the Netherlands and Germany (but not in Belgium). It receives protection by chapter 2 of the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages. Limburgish has been influenced by the Rhinelandic dialects like the Cologne dialect Kölsch, and has had a somewhat different development since the late Middle Ages.

Dutch Low Saxon has also been elevated by the Netherlands (and by Germany) to the legal status of streektaal (regional language) according to the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages.

Gronings is very much alive in the province of Groningen, although it is not so popular in the city of the same name.

The Vlaemsch (West Flemish) dialect is listed as a minority language in France, however only a very small and ageing minority of the French-Flemish population still speaks and understands West Flemish.

Belgium didn't choose to list any dialect as a minority language, because of the already complicated language situation that appears in the country.

Recent use

Dutch dialects and regional languages are not spoken as often as they used to be. Recent research by Geert Driessen shows that the use of dialects and regional languages among both Dutch adults and youth is in heavy decline. In 1995, 27 percent of the Dutch adult population spoke a dialect or regional language on a regular basis, while in 2011 this was no more than 11 percent. In 1995, 12 percent of the primary school aged children spoke a dialect or regional language, while in 2011 this had declined to 4 percent. Of the three officially recognized regional languages Limburgish is spoken most (in 2011 among adults 54%, among children 31%) and Dutch Low Saxon least (adults 15%, children 1%); Frisian occupies a middle position (adults 44%, children 22%). In Belgium, however, dialects are very much alive; many senior citizens there are unable to speak standard Dutch.

Flanders

In Flanders, there are four main dialect groups:

- West Flemish (West-Vlaams) including French Flemish in the far North of France,

- East Flemish (Oost-Vlaams),

- Brabantian (Brabants), which includes several main dialect branches, including Antwerpian, and

- Limburgish (Limburgs).

Some of these dialects, especially West and East Flemish, have incorporated some French loanwords in everyday language. An example is fourchette in various forms (originally a French word meaning fork), instead of vork. Brussels is especially heavily influenced by French because roughly 85% of the inhabitants of Brussels speak French.

The different dialects show many sound shifts in different vowels (even shifting between diphthongs and monophthongs), and in some cases consonants also shift pronunciation.

For example, an oddity of West Flemings (and to a lesser extent, East Flemings) is that, the voiced velar fricative (written as "g" in Dutch) shifts to a voiced glottal fricative (written as "h" in Dutch), while the letter "h" in West Flemish becomes mute (just like in French). As a result, when West Flemish try to talk Standard Dutch, they're often unable to pronounce the g-sound, and pronounce it similar to the h-sound. This leaves f.e. no difference between "held" (hero) and "geld" (money). Or in some cases, they are aware of the problem, and hyper-correct the "h" into a voiced velar fricative or g-sound. Again leaving no difference.

Next to sound shifts, there are ample examples of suffix differences. Often simple suffix shifts (like switching between -tje, -ske, -ke, -je, ...), sometimes the suffixes even depend on quite specific grammar rules for a certain dialect. Again taking West Flemish as an example. In that language, the words "ja" (yes) and "nee" (no) are also conjugated to the (often implicit) subject of the sentence. These separate grammar rules are a lot more difficult to imitate correctly than simple sound shifts, making it easy to recognise people who didn't grow up in a certain region, even decades after they moved.

Dialects are still most often spoken in rural areas, however, a lot of cities have a distinct city dialect. For example, the city of Ghent has very distinct "g", "e" and "r" sounds, differing a lot from the surrounding villages. Or the Brussels dialect, that's the original Brabantian dialect combined with Walloon and French dialects.

Some Flemish dialects are so distinct that they might be considered as separate language variants, although the strong significance of language in Belgian politics would prevent the government from classifying them as such. West Flemish in particular has sometimes been considered a distinct variety. Dialect borders of these dialects do not correspond to present political boundaries, but reflect older, medieval divisions.

The Brabantian dialect group, for instance, also extends to much of the south of the Netherlands, and so does Limburgish. West Flemish is also spoken in Zeelandic Flanders (part of the Dutch province of Zeeland), and by older people in French Flanders (a small area that borders Belgium).

Sister and daughter languages

Many native speakers of Dutch, both in Belgium and the Netherlands, assume that Afrikaans and West Frisian are 'deviant' dialects of Dutch. In fact, they are separate and different languages, a daughter language and a sister language, respectively. Afrikaans evolved mainly from 17th century Dutch dialects, but had influences from various other languages in South Africa. However, it is still largely mutually intelligible with Dutch. (West) Frisian evolved from the same West Germanic branch as Anglo-Saxon and is less akin to Dutch.

Phonology

This section gives only a general overview of the phonemes of Dutch. For further details on different realisations of phonemes, dialectal differences and example words, see the full article at Dutch phonology.

Consonants

Like most Germanic languages, the Dutch consonant system did not undergo the High German consonant shift and has a syllable structure that allows fairly complex consonant clusters. Dutch also retains full use of the velar fricatives that were present in Proto-Germanic, but lost or modified in many other Germanic languages.

Dutch has final-obstruent devoicing: at the end of a word, voicing distinction is neutralised and all obstruents are pronounced voiceless. For example, goede ("good") is /ˈɣudə/ but the related form goed is /ɣut/.

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Velar/ Uvular |

Glottal | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | ŋ | |||

| Plosive | p b | t d | k ɡ | (ʔ) | ||

| Fricative | f v | s z | ʃ ʒ | x ɣ | ɦ | |

| Trill | r | |||||

| Approximant | ʋ | l | j | |||

Notes:

- [ʔ] is not a separate phoneme in Dutch, but is inserted before vowel-initial syllables within words after /a/ and /ə/ and often also at the beginning of a word.

- The realization of /r/ phoneme varies considerably from dialect to dialect and even between speakers in the same dialect area. Common realisations are an alveolar trill [r], alveolar tap [ɾ], uvular trill [ʀ], voiced uvular fricative [ʁ], and alveolar approximant [ɹ].

- The realization of /ʋ/ also varies somewhat by area and speaker. The main realisation is a labiodental approximant [ʋ], but some speakers, particularly in the south, use a bilabial approximant [β̞] or a labiovelar approximant [w].

- The lateral /l/ is slightly velarized postvocalically in most dialects, particularly in the north.[93]

- /x/ and /ɣ/ may be true velars [x] and [ɣ], uvular [χ] and [ʁ] or palatal [ç] and [ʝ]. The more palatal realisations are common in southern areas, while uvulars are common in the north.

- Some northern dialects have a tendency to devoice all fricatives regardless of environment. This is particularly common with /ɣ/ but can affect others as well.

- /ʃ/ and /ʒ/ are not native phonemes of Dutch, and usually occur in borrowed words, like show and bagage ('baggage').

- /ɡ/ is not a native phoneme of Dutch and only occurs in borrowed words, like garçon.

Vowels

Dutch has an extensive vowel inventory, as is common for Germanic languages. Vowels can be grouped as back rounded, front unrounded and front rounded. They are also traditionally distinguished by length or tenseness.

Vowel length is not always considered a distinctive feature in Dutch phonology, because it normally co-occurs with changes in vowel quality. One feature or the other may be considered redundant, and some phonemic analyses prefer to treat it as an opposition of tenseness. However, even if not considered part of the phonemic opposition, the long/tense vowels are still realised as phonetically longer than their short counterparts. The changes in vowel quality are also not always the same in all dialects, and in some there may be little difference at all, with length remaining the primary distinguishing feature. And while it is true that older words always pair vowel length with a change in vowel quality, new loanwords have reintroduced phonemic oppositions of length. Compare zonne(n) [ˈzɔnə] ("suns") versus zone [ˈzɔːnə] ("zone") versus zonen [ˈzoːnə(n)] ("sons"), or kroes [krus] ("mug") versus cruise [kruːs] ("cruise").

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- The distinction between /i y u/ and /iː yː uː/ is only slight, and may be considered allophonic for most purposes. However, some recent loanwords have introduced distinctively long /iː yː uː/, making the length distinction marginally phonemic.

- The long close-mid vowels /eː øː oː/ are realised as slightly closing diphthongs [eɪ øʏ oʊ] in many northern dialects.

- The long open-mid vowels /ɛː œː ɔː/ only occur in a handful of loanwords, mostly from French.

- The long close and close-mid vowels are often pronounced more closed or as centering diphthongs before an /r/ in the syllable coda. This may occur before coda /l/ as well.

Dutch also has several diphthongs. All of them end in a close vowel (/i y u/), but may begin with a variety of other vowels. They are grouped here by their first element.

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Notes:

- /ɛi œy ɑu/ are the most common diphthongs and commonly the only ones considered "true" phonemes in Dutch. /ɑi/ and /ɔi/ are rare and occur only in some words. The "long/tense" diphthongs, while they are indeed realised as proper diphthongs, are generally analysed phonemically as a long/tense vowel followed by a glide /j/ or /ʋ/.

Phonotactics

The syllable structure of Dutch is (C)(C)(C)V(C)(C)(C)(C). Many words, as in English, begin with three consonants; for example, straat /straːt/ (street). There are words that end in four consonants, e.g., herfst /ɦɛrfst/ 'autumn', ergst /ɛrxst/ 'worst', interessantst 'most interesting', sterkst /stɛrkst/ 'strongest', the last three of which are superlative adjectives.

The highest number of consonants in a single cluster is found in the word slechtstschrijvend /ˈslɛxtstˌsxrɛi̯vənt/ 'writing worst' with 7 consonant phonemes. Similar is angstschreeuw ![]() /ˈɑŋstsxreːu̯/ "scream in fear", with six in a row.

/ˈɑŋstsxreːu̯/ "scream in fear", with six in a row.

Polder Dutch

A notable change in pronunciation has been occurring in younger generations in the provinces of Utrecht, North and South Holland, which has been dubbed "Polder Dutch" by Jan Stroop.[94] These speakers pronounce ⟨ij/ei⟩, ⟨ou⟩, and ⟨ui⟩, which used be pronounced as /ɛi/, /ʌu/, and /œy/, increasingly lowered, as [ai], [au], and [ay] respectively. Instead, /eː/, /oː/, and /øː/ are pronounced as diphthongs now, as [ɛi], [ɔu], and [œy] respectively, which makes this change an instance of a chain shift.

This change is interesting from a sociolinguistic point of view because it has apparently happened relatively recently, in the 1970s, and was pioneered by older well-educated women from the upper middle classes.[95] The lowering of the diphthongs has long been current in many Dutch dialects, and is comparable to the English Great Vowel Shift, and the diphthongisation of long high vowels in Modern High German, which centuries earlier reached the state now found in Polder Dutch. Stroop theorizes that the lowering of open-mid to open diphthongs is a phonetically "natural" and inevitable development and that Dutch, after having diphthongised the long high vowels like German and English, "should" have lowered the diphthongs like German and English as well.

Instead, he argues, this development has been artificially frozen in an "intermediate" state by the standardisation of Dutch pronunciation in the 16th century, where lowered diphthongs found in rural dialects were perceived as ugly by the educated classes and accordingly declared substandard. Now, however, in his opinion, the newly affluent and independent women can afford to let that natural development take place in their speech. Stroop compares the role of Polder Dutch with the urban variety of British English pronunciation called Estuary English.

Among Belgian Dutch speakers and speakers from other regions in the Netherlands, this vowel shift is not taking place, as ⟨ij⟩, ⟨ou⟩, and ⟨ui⟩ are normally pronounced as the monophthongs [ɛː], [ɔː] and [œː].

Grammar

Dutch is grammatically similar to German, such as in syntax and verb morphology (for a comparison of verb morphology in English, Dutch and German, see Germanic weak verb and Germanic strong verb). Dutch has grammatical cases, but these are now mostly limited to pronouns and a large number of set phrases. Inflected forms of the articles are also often found in surnames and toponyms.

Standard Dutch has three genders: masculine, feminine and neuter. In general, Belgian speakers distinguish masculine and feminine words (see Gender in Dutch). This three gender system is similar to the one in German. For most non-Belgian speakers, the masculine and feminine genders have merged to form the common gender (de), while the neuter (het) remains distinct as before. This gender system is similar to those of most Continental Scandinavian languages. As in English, but to a lesser degree, the inflectional grammar of the language (e.g., adjective and noun endings) has simplified over time.

Genders and cases

Modern Dutch has mostly lost its case system.[96] However, certain idioms and expressions continue to include now archaic case declensions. The table of definite articles below demonstrates that contemporary Dutch is less complex than German. The article has just two forms, de and het, more complex than English, which has only "the". The use of the older inflected form den in the dative or accusative as well as use of 'der' in the dative are restricted to numerous set phrases, surnames and toponyms.

| Dutch | German | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Masculine singular | Feminine singular | Neuter singular | Plural (any gender) | Masculine singular | Feminine singular | Neuter singular | Plural (any gender) | |

| Nominative | de | de | het | de | der | die | das | die |

| Genitive | van de / des | van de / der | van het / des | van de / der | des | der | des | der |

| Dative | (aan / voor) de | (aan / voor) de | (aan / voor) het | (aan / voor) de | dem | der | dem | den |

| Accusative | de | de | het | de | den | die | das | die |

In modern Dutch, the genitive articles 'des' and 'der' are commonly used in idioms. Other usage is typically considered archaic, poetic or stylistic. In most circumstances, the preposition 'van' is instead used, followed by the normal definitive article 'de' or 'het'. For the idiomatic use of the articles in the genitive, see for example:

- Masculine singular: "des duivels" (litt: of the devil) (common proverbial meaning: Seething with rage)

- Feminine singular: het woordenboek der Friese taal (the dictionary of the Frisian language)

- Neuter singular: de vrouw des huizes (the lady of the house)

- Plural: de voortgang der werken (the progress of (public) works)

In contemporary usage, the genitive case still occurs a little more often with plurals than with singulars, as the plural article is 'der' for all genders and no special noun inflection must be taken account of. 'Der' is commonly used in order to avoid reduplication of 'van', e.g. het merendeel der gedichten van de auteur instead of het merendeel van de gedichten van de auteur ("the bulk of the author's poems").

There are also genitive forms for the pronoun die/dat ("that [one], those [ones]"), namely diens for masculine and neuter singulars and dier for feminine singular and all plurals. Although usually avoided in common speech, these forms can be used instead of possessive pronouns to avoid confusion, these forms often occur in writing . Compare:

- Hij vertelde van zijn zoon en zijn vrouw. – He told about his son and his (own) wife.

- Hij vertelde van zijn zoon en diens vrouw. – He told about his son and the latter's wife.

Analogically, the relative and interrogative pronoun wie ("who") has the genitive forms wiens and wier (corresponding to English "whose", but less frequent in use).

Dutch also has a range of fixed expressions that make use of the genitive articles, which can be abbreviated using apostrophes. Common examples include "'s ochtends" (with 's as abbreviation of des; in the morning) and "desnoods" (lit: of the need, translated: if necessary).

The Dutch written grammar has simplified over the past 100 years: cases are now mainly used for the pronouns, such as ik (I), mij, me (me), mijn (my), wie (who), wiens (whose: masculine or neuter singular), wier (whose: feminine singular; masculine, feminine or neuter plural). Nouns and adjectives are not case inflected (except for the genitive of proper nouns (names): -s, -'s or -'). In the spoken language cases and case inflections had already gradually disappeared from a much earlier date on (probably the 15th century) as in many continental West Germanic dialects.

Inflection of adjectives is more complicated. The adjective receives no ending with indefinite neuter nouns in singular (as with een /ən/ 'a/an'), and -e in all other cases. (This was also the case in Middle English, as in "a goode man".) Note that fiets belongs to the masculine/feminine category, and that water and huis are neuter.

| Masculine singular or feminine singular | Neuter singular | Plural (any gender) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Definite (with definite article or pronoun) |

de mooie fiets (the beautiful bicycle) | het mooie huis (the beautiful house) | de mooie fietsen (the beautiful bicycles) de mooie huizen (the beautiful houses) |

| Indefinite (with indefinite article or no article and no pronoun) |

een mooie fiets (a beautiful bicycle) koude soep (cold soup) | een mooi huis (a beautiful house) koud water (cold water) | mooie fietsen (beautiful bicycles) mooie huizen (beautiful houses) |

An adjective has no e if it is in the predicative: De soep is koud.

More complex inflection is still found in certain lexicalized expressions like de heer des huizes (literally, the man of the house), etc. These are usually remnants of cases (in this instance, the genitive case which is still used in German, cf. Der Herr des Hauses) and other inflections no longer in general use today. In such lexicalized expressions remnants of strong and weak nouns can be found too, e.g. in het jaar des Heren (Anno Domini), where "-en" is actually the genitive ending of the weak noun. Also in this case, German retains this feature. Though the genitive is widely avoided in speech.

Word order

Dutch exhibits subject–object–verb word order, but in main clauses the conjugated verb is moved into the second position in what is known as verb second or V2 word order. This makes Dutch word order almost identical to that of German, but often different from English, which has subject–verb–object word order and has since lost the V2 word order that existed in Old English.[97]

An example sentence used in some Dutch language courses and textbooks is "Ik kan mijn pen niet vinden omdat het veel te donker is", which translates into English word for word as "I can my pen not find because it far too dark is", but in standard English word order would be written "I cannot find my pen because it is far too dark". If the sentence is split into a main and subclause and the verbs highlighted, the logic behind the word order can be seen.

Main clause: "Ik kan mijn pen niet vinden "

Verbs are placed in the final position, but the conjugated verb, in this case "kan" (can), is made the second element of the clause.

Subclause: "omdat het veel te donker is "

The verb or verbs always go in the final position.

In an interrogative main clause the usual word order is: conjugated verb followed by subject; other verbs in final position:

"Kun jij je pen niet vinden?" (literally "Can you your pen not find?") "Can't you find your pen?"

In the Dutch equivalent of a wh-question the word order is: interrogative pronoun (or expression) + conjugated verb + subject; other verbs in final position:

"Waarom kun jij je pen niet vinden?" ("Why can you your pen not find?") "Why can't you find your pen?""

In a tag question the word order is the same as in a declarative clause:

"Jij kunt je pen niet vinden?" ("You can your pen not find?") "You can't find your pen?""

A subordinate clause does not change its word order: "Kun jij je pen niet vinden omdat het veel te donker is?" ("Can you your pen not find because it far too dark is?") "Can you not find your pen because it's too dark?""

Diminutives

Dutch nouns can take endings for size: -je for singular diminutive and -jes for plural diminutive. Between these suffixes and the radical can come extra letters depending on the ending of the word:

- boom (tree) – boompje

- ring (ring) – ringetje

- koning (king) – koninkje

- tien (ten) – tientje (a ten euro note)

These diminutives are very common. As in German, all diminutives are neuter. In the case of words like "het meisje" (the girl), this is different from the natural gender. A diminutive ending can also be appended to an adverb or adjective (but not when followed by a noun).

- klein (little, small) – een kleintje (a small one)

In Belgian Dutch, dimunitives are frequently formed with -ke(n), being similar to German -chen, but only occur rarely in written, in stead giving preference to the dimunitives using -je.

Compounds

Like most Germanic languages, Dutch forms noun compounds, where the first noun modifies the category given by the second (hondenhok = doghouse). Unlike English, where newer compounds or combinations of longer nouns are often written in open form with separating spaces, Dutch (like the other Germanic languages) either uses the closed form without spaces (boomhuis = tree house) or inserts a hyphen (VVD-coryfee = outstanding member of the VVD, a political party). Like German, Dutch allows arbitrarily long compounds, but the longer they get, the less frequent they tend to be.

The longest serious entry in the Van Dale dictionary is ![]() wapenstilstandsonderhandeling (ceasefire negotiation). Leafing through the articles of association (Statuten) one may come across a 30-letter

wapenstilstandsonderhandeling (ceasefire negotiation). Leafing through the articles of association (Statuten) one may come across a 30-letter ![]() vertegenwoordigingsbevoegdheid (authorisation of representation). An even longer word cropping up in official documents is ziektekostenverzekeringsmaatschappij (health insurance company) though the shorter ziektekostenverzekeraar (health insurer) is more common.

vertegenwoordigingsbevoegdheid (authorisation of representation). An even longer word cropping up in official documents is ziektekostenverzekeringsmaatschappij (health insurance company) though the shorter ziektekostenverzekeraar (health insurer) is more common.

Notwithstanding official spelling rules, some Dutch people, like some Scandinavians and Germans, nowadays tend to write the parts of a compound separately, a practice sometimes dubbed de Engelse ziekte (the English disease).[98][99]

Vocabulary

Dutch vocabulary is predominantly Germanic in origin, considerably more so than English. This difference is mainly due to the heavy influence of Norman on English, and to Dutch patterns of word formation, such as the tendency to form long and sometimes very complicated compound nouns, being more similar to those of German and the Scandinavian languages. The Dutch vocabulary is one of the richest in the world and comprises at least 268,826 headwords.[100] In addition, the Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal (English: "Dictionary of the Dutch Language") is the largest dictionary in the world in print and has over 430,000 entries of Dutch words.[101]

Like English, Dutch includes words of Greek and Latin origin. French has also contributed a large number of words, most of which have entered into Dutch vocabulary via the Netherlands and not via Belgium, in spite of the cultural and economic dominance exerted by French speakers in Belgium until the first half of the 20th century. This happened because the status French enjoyed as the language of refinement and high culture inspired the affluent upper and upper-middle classes in the Netherlands to adopt many French terms into the language. In Belgium no such phenomenon occurred, since members of the upper and upper-middle classes would have spoken French rather than Frenchify their Dutch. French terms heavily influenced Dutch dialects in Flanders, but Belgian speakers did (and do) tend to resist French loanwords when using standard Dutch. Nonetheless some French loanwords of relatively recent date have become accepted in standard Dutch, also in Belgium, albeit with a shift in meaning and not as straight synonyms for existing Dutch words. For example, "blesseren" (from French blesser, to injure) is almost exclusively used to refer to sports injuries, while in other contexts the standard Dutch verbs "kwetsen" and "verwonden" continue to be used.

Influence from German (i.e salonfähig, ausdauer, überhaupt, sowieso) is also present but less visible due to the tendency and possibility to translate German compound words into their Dutch components (like dagdagelijks from tagtäglich, zelfmoord from Selbstmord and leenwoord from Lehnwort). In informal conversations and in many professions, there is an increase of English loanwords, rather often pronounced or applied in a different way (see Dutch pseudo-anglicisms). The influx of English words is maintained by the dominance of English in the mass media and on the Internet.

The most important dictionary of the modern Dutch language is the Van Dale groot woordenboek der Nederlandse taal,[102] more commonly referred to as the Dikke van Dale ("dik" means "thick"). However, it is dwarfed by the 45,000-page Woordenboek der Nederlandsche Taal, a scholarly endeavour that took 147 years from initial idea to first edition.

Writing system

Dutch is written using the Latin script. Dutch uses one additional character beyond the standard alphabet, the digraph IJ. It has a relatively high proportion of doubled letters, both vowels and consonants, due to the formation of compound words and also to the spelling devices for distinguishing the many vowel sounds in the Dutch language. An example of five consecutive doubled letters is the word voorraaddoos (food storage container).

The diaeresis (Dutch: trema) is used to mark vowels that are pronounced separately. In the most recent spelling reform, a hyphen has replaced the diaeresis in compound words (i.e., if the vowels originate from separate words, not from prefixes or suffixes), e.g. zeeëend (seaduck) is now spelled zee-eend.

The acute accent occurs mainly in loanwords like café, but can also be used for emphasis or to differentiate between two forms. Its most common use is to differentiate between the indefinite article 'een' (a, an) and the numeral 'één' (one); also 'hé' (hey, also written 'hee').

The grave accent is used to clarify pronunciation ('hè' [what?, what the ...?, tag question 'eh?'], 'bèta') and in loanwords ('caissière' [female cashier], 'après-ski'). In the recent spelling reform, the accent grave was dropped as stress sign on short vowels in favour of the acute accent (e.g. 'wèl' was changed to 'wél').

Other diacritical marks such as the circumflex only occur in a few words, most of them loanwords from French. The characters 'Ç', 'ç', 'Ñ' or 'ñ' can also be found in the Dutch language but the words that contain one of these characters are loanwords too and these words are inherited from Spain and Portugal. They don't occur very often.

The official spelling is set by the Wet schrijfwijze Nederlandsche taal (Law on the writing of the Dutch language; Belgium 1946, Netherlands 1947; based on a 1944 spelling revision; both amended in the 1990s after a 1995 spelling revision). The Woordenlijst Nederlandse taal, more commonly known as "het groene boekje" (i.e. "the green booklet", because of its colour), is usually accepted as an informal explanation of the law. However, the official 2005 spelling revision, which reversed some of the 1995 changes and made new ones, has been welcomed with a distinct lack of enthusiasm in both the Netherlands and Belgium. As a result, the Genootschap Onze Taal[103] (Our Language Society) decided to publish an alternative list, "het witte boekje" ("the white booklet"), which tries to simplify some complicated rules and offers several possible spellings for many contested words. This alternative orthography is followed by a number of major Dutch media organisations but mostly ignored in Belgium.

Alphabet

| Letter | Letter name | Spelling alphabet[104] |

|---|---|---|

| A | [aː] | Anton |

| B | [beː] | Bernhard |

| C | [seː] | Cornelis |

| D | [deː] | Dirk |

| E | [eː] | Eduard |

| F | [ɛf] | Ferdinand |

| G | [ɣeː][105] | Gerard |

| H | [ɦaː] | Hendrik |

| I | [i] | Izaak |

| J | [jeː] | Johan/Jacob |

| K | [kaː] | Karel |

| L | [ɛɫ] | Lodewijk/Leo |

| M | [ɛm] | Maria |

| N | [ɛn] | Nico |

| O | [oː] | Otto |

| P | [peː] | Pieter |

| Q[106] | [ky] | Quirinius/Quinten |

| R | [ɛɾ] | Richard/Rudolf |

| S | [ɛs] | Simon |

| T | [teː] | Theodoor |

| U | [y] | Utrecht |

| V | [veː] | Victor |

| W | [ʋeː] | Willem |

| X[106] | [ɪks] | Xantippe |

| Y[106] | [ɛɪ][107] | Ypsilon |

| IJ[108] | IJmuiden/IJsbrand | |

| Z | [zɛt] | Zacharias |

Sound to spelling correspondences

Dutch uses the following letters and letter combinations. Note that for simplicity, dialectal variation and subphonemic distinctions are not always indicated. See Dutch phonology for more information.

The following list shows letters and combinations, along with their pronunciations, that are found in modern native or nativised vocabulary:

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The following additional letters and pronunciations appear in non-native vocabulary, or words using older, obsolete spellings.

|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Dutch as a foreign language

As a foreign language, Dutch is mainly taught in primary and secondary schools in areas adjacent to the Netherlands and Flanders. In French-speaking Belgium, over 300,000 pupils are enrolled in Dutch courses, followed by over 20,000 in the German states of Lower Saxony and North Rhine-Westphalia, and over 7,000 in the French region of Nord-Pas de Calais (of which 4,550 are in primary school).[137] Dutch is the obligatory medium of instruction in schools in Suriname, even for non-native speakers.[138] Dutch is taught in various educational centres in Indonesia, the most important of which is the Erasmus Language Centre (ETC) in Jakarta. Each year, some 1,500 to 2,000 students take Dutch courses there.[139] In total, several thousand Indonesians study Dutch as a foreign language.[140]

At an academic level, Dutch is taught in over 225 universities in more than 40 countries. About 10,000 students worldwide study Dutch at university.[46] The largest number of faculties of neerlandistiek can be found in Germany (30 universities), followed by France and the United States (20 each). Five universities in the United Kingdom offer the study of Dutch.[137][141] Owing to centuries of Dutch rule in Indonesia, many old documents are written in Dutch. Many universities therefore include Dutch as a source language, mainly for law and history students.[45] In Indonesia this involves about 35,000 students.[46] In South Africa, the number is difficult to estimate, since the academic study of Afrikaans inevitably includes the study of Dutch.[46] Elsewhere in the world, the number of people learning Dutch is relatively small.

Popular misconceptions

The language of Flanders

Dutch is the language of government, education, and daily life in Flanders, the northern part of Belgium. There is no officially recognized language called "Flemish", and both the Dutch and Belgian governments adhere to the standard Dutch (Algemeen Nederlands) defined by the Nederlandse Taalunie ("Dutch Language Union").

The actual differences between the spoken standard language of Dutch and Belgian speakers are comparable to the differences between American and British English or the German spoken in Germany and Austria. In other words, most differences are rather a matter of accent than of grammar. Some of these differences are recognized by the Taalunie and major dictionaries as being interchangeably valid, although some dictionaries and grammars may mark them as being more prevalent in one region or the other.

The use of the word Vlaams ("Flemish") to describe Standard Dutch for the variations prevalent in Flanders and used there, is common in the Netherlands and Belgium.

Dutch and German as sister languages

The dialect group from which Dutch is largely derived, Low Franconian, belongs to the whole of the continental West Germanic dialect set. This whole is sometimes imprecisely indicated by the word "German", but it might as well be called "Dutch". Indeed the Low Franconian dialects and languages are morphologically closer to the original form of Western Germanic than the High German from which standard German is derived. It is quite appropriate to call modern Dutch and High German sister languages, only they are derived not from one and the same common variety, but from cognate mother vernaculars of Continental West Germanic. The view about mutual intelligibility between Dutch and German varies.[10][11]

No intrinsic quality of the whole of the component dialects favours one standard over the other: both were rivals and historical contingency decided the range of their use. The state border does not reflect dialectal subdivisions. Only since the dialect continuum of continental West Germanic was broken by the 19th century introduction of mass education have the respective ranges been fixed; in the 18th century standard Dutch was still used as the normal written standard in the Lower Rhine, the county of Bentheim and East Frisia, now all part of Germany. See also Meuse-Rhenish.

Low Dietsch

Low Dietsch (Dutch: Platdiets, Limburgish: Platduutsj, French: Thiois or Platdutch) is a term mainly used within the Flemish terminology for the transitional Limburgish-Ripuarian dialects of a number of towns and villages in the north-east of the Belgian province of Liege, such as Gemmenich, Homburg, Montzen and Welkenraedt.

Dutch and English as sister languages

Dutch has a relatively close genetic relationship to the descendants of Old and Middle English (such as English and Scots), though less than the Frisian languages (such as West Frisian) have to English. Both Dutch and English belong to the West Germanic languages and both lack most or all of the High German consonant shift that characterizes the descendants of Middle High German (such as German and Yiddish). Because of their close common relationship many English words are essentially identical to their Dutch lexical counterparts, either in spelling (begin) or pronunciation (boek = book, diep = deep), or both (lip); these cognates or in other ways related words are excluded from this list.

Though Dutch and English are relatively closely related, Dutch is less influenced by the French language and therefore contains fewer French loan words than the English language.

Pennsylvania Dutch

Pennsylvania Dutch, a West Central German variety called Deitsch by its speakers, is not a form of Dutch. The word "Dutch" has historically been used for all speakers of continental West Germanic languages, including, the Dutch people, Flemish, Austrians, Germans, and the German-speaking Swiss. It is cognate with the Dutch archaism Diets, meaning "Dutch", and the German self-designation Deutsch. The use of the term "Dutch" exclusively for the language of Belgium, or for the inhabitants of the Netherlands or some of its former colonies, dates from the early 16th century. The name "Dutch" for the Pennsylvania dialect also stems from the way "Deutsch" is pronounced in the dialect itself.

Pennsylvania Dutch must not be confused with Jersey Dutch as spoken in Upstate New York in former ages, and even until the 1950s in New Jersey, being Dutch-based creole or pidgin languages.

Dutch, not Deutsch

The resemblance of the English-language word "Dutch" (referring to the language spoken in the Netherlands and Flanders) and the Dutch-language word Duits and German-language word Deutsch (meaning the language spoken in Germany, Austria, and much of Switzerland) is not accidental, since both derive from the Germanic word þiudiskaz ("of the people, popular, vulgar, vernacular"; that is, as opposed to Latin).

Until roughly the 16th century, speakers of all the varieties of West Germanic from the mouth of the Rhine to the Alps had been accustomed to refer to their native speech as the vernacular. This was Dietsch or Duitsch in Middle Dutch and what would eventually stabilize as Deutsch further south.

English-speakers took the word Duitsch from their nearest Germanic-speaking neighbours in the Low Countries, and having anglicized it as Dutch[142] used it to refer to those neighbours and to the language they spoke. Meanwhile, however, especially after their secession from the Holy Roman Empire (i.e., Germany) in 1648, the Dutch began increasingly to refer to their own language as Nederlandsch (from which today's Nederlands) in distinction from the people and speech of the Empire itself – Duitsch (now Duits) – with the result that 'Dutch' and Deutsch now refer to two different languages. About that time (as in Jonathan Swift's Gulliver's Travels), the English called Dutch "Low Dutch" and German "High Dutch", but eventually "German" won out over "High Dutch" due to the German-speaking territories being known as "Germany"[143] named after Germania.

See also

| Dutch edition of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia |

- Afrikaans

- Differences between Afrikaans and Dutch

- Bargoens

- Dutch braille

- Dutch dialects

- Dutch grammar

- Dutch Language Union

- Dutch linguistic influence on military terms

- Dutch literature

- Dutch name

- Dutch orthography

- Dutch-based creole languages

- Flemish

- French Flemish

- Grand Dictation of the Dutch Language

- Indo-European languages

- Istvaeones

- List of English words of Dutch origin

- Low Dietsch

- Low Franconian

- Meuse-Rhenish

- Middle Dutch

- Old Dutch

- Old Frankish

Notes

- ↑ In France a historical dialect called French Flemish is spoken. There are about 80,000 Dutch speakers in France; see Simpson 2009, p. 307. In French Flanders, only a remnant of between 50,000 to 100,000 Flemish-speakers remain; see Berdichevsky 2004, p. 90. Flemish is spoken in the north-west of France by an estimated population of 20,000 daily speakers and 40,000 occasional speakers; see European Commission 2010.

A dialect continuum exists between Dutch and German through the South Guelderish and Limburgish dialects.