Dusit Palace

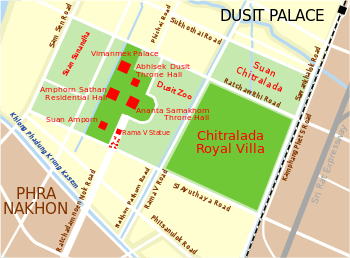

Dusit Palace (Thai: พระราชวังดุสิต, Phra Ratcha Wang Dusit) is a compound of royal residences in Bangkok, Thailand. Constructed over a large area north of Rattanakosin Island between 1897 and 1901 by King Chulalongkorn (Rama V). The palace, originally called Wang Suan Dusit or Dusit Garden Palace (วังสวนดุสิต), eventually became the primary (but not official) place of residence of the King of Thailand, including King Rama V, King Vajiravudh (Rama VI), King Prajadhipok (Rama VII) and the present monarch King Bhumibol Adulyadej (Rama IX). The palace covers an area of over 64,749 square metres (696,950 sq ft) and is dotted between gardens and lawns with 13 different royal residences. Dusit Palace is surrounded by Ratchwithi Road in the north, Sri Ayutthaya Road in the south, Rachasima Road in the west and U-Thong Nai Road on the east.

History

Background

Since 1782 and the foundation of Bangkok as the capital city of the Kingdom of Siam, the monarchs of the Chakri Dynasty has resided at the Grand Palace by the Chao Phraya river. The palace became the focal point of the city as well as a seat of the royal government and the home of the king and his court (his children and his polygamous household). During the reign of King Chulalongkorn, the Grand Palace went through a great transformation, with massive reconstructions and additions being made in the main Middle Court (state buildings) and the Inner Court (residential buildings) of the palace. These changes were brought about as a means to modernize the palace as well as accommodate its growing population. As a result the palace, particularly the Inner Court, became extremely overcrowded. The Grand Palace also became stiflingly hot during the summer months, with the passage of air being blocked by the closely clustered new buildings. Epidemics once started, were liable to spread easily within its crowded compound. The king, who enjoyed taking long walks for exercise and pleasure, often felt unwell after prolonged stays inside the Grand Palace. Consequently he took frequent trips into the country to take relief of this condition.[1]

Celestial palace

Chulalongkorn got the idea of having a royal residence with spacious gardens on the outskirts of the capital from European monarchs during his trip to Europe in 1897. When he returned to Bangkok he began to built a new royal compound within walking distance of the Grand Palace. He began by acquiring several connect farmlands and orchards between Padung Krung Kasem and Samsen canals from funds of his Privy Purse. The king decided to name this area Suan Dusit meaning 'Celestial Garden'. The first building within this area was a single story wooden structure, used by the king, his consorts and his children for occasional stays. In 1890 plans for a permanent set of residences are drawn up and constructions were begun under the supervision of Prince Narisara Nuvadtivongs (the king's brother) and C. Sandreczki (a German architect, responsible for the Boromphiman Palace). Apart from the Prince all other members of the team were Europeans. When it became clear that Chulalongkorn preferred to stay within the garden, with only occasional visits to the Grand Palace for state and royal ceremonies, the name was changed to Wang Dusit meaning 'Celestial Dwelling'.[1]

Apart from taking his long walks, Chulalongkorn also indulge in a new and fashionable pastime of cycling. Even before he took permanent residence at Dusit Palace, he would take his entourage cycling from the Grand Palace to the garden and back. With bicycling trips often taking up all day. This pathway connecting the Grand Palace to Dusit Palace eventually became the Rajadamnern Avenue. The construction of both Dusit Palace and the Rajadamnern Avenue holds particular significance in the urban development of Bangkok, by allowing and encouraging the expansion of Bangkok outside its city walls and the traditional confines of the Rattanakosin area. The palace expanded Bangkok northwards, while the avenue accommodated further growth. The avenue extended from the palace, starting in front of the Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall and the Royal Plaza along southwards along the Makawan Rangsant and Phanfah Lielas bridges then westwards across the Phanbipob Liela bridge, then southwards again long the Sanam Luang unto the Grand Palace.[2]

Upon Chulalongkorn's return from his second European tour in 1908, he expanded the palace northward, creating an additional private garden called Suan Sunandha (สวนสุนันทา), in honour of his first consort Queen Sunandha Kumariratana, who died in 1880. The garden became the setting of residential houses belonging to the king's consorts and children. Chulalongkorn lived at the palace until his death at the Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall on 23 October 1910 of kidney disease.

Sixth, Seventh and Eighth reigns

His successor King Vajiravudh contributed to the expansion of the palace by the construction in 1913 of another garden called Suan Chitralada (สวนจิตรลดา), situated between Dusit Palace and Phaya Thai Palace. Within this garden he had a residential villa built and named it Phra Thamnak Chitralada Rahothan or the Chitralada Royal Villa (พระตำหนักจิตรลดารโหฐาน). Later in 1925 during the reign of King Prajadhipok, this garden was incorporated by royal command as part of Dusit Palace. At its greatest extent the palace occupied over 768,902 square metres (8,276,390 sq ft) of land. In 1932 the absolute monarchy was abolished and part of the Dusit Palace was reduced and transferred to the constitutional government. This included the Khao Din Wana (เขาดินวนา) to the east of the palace, which was given in 1938 to the Bangkok City Municipality by King Ananda Mahidol to create a public park, which later became Dusit Zoo. The Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall was also appropriated as the permanent meeting place of the National Assembly of Thailand.

Present reign

During the reign of the present monarch King Bhumibol Adulyadej, the Chitralada Royal Villa and garden became the de facto primary residence of the king and the royal family. This area is then commonly referred to as the Chitralada Palace. In 1970 the National Assembly of Thailand requested a new plot of land for the building of a new legislature, as the Ananta Samkhom Throne Hall had become too small and was unable to accommodate the growing assembly and its secretariat. The King granted a plot of land within Dusit Palace immediately north of the Throne Hall for the building of a new Parliament House of Thailand. With the completion of this new building the Ananta Samkhom Throne Hall was returned to the king as part of the palace once more.

Currently several museums and exhibitions are displayed inside the various buildings within the palace precinct, only a few of these are open to the public.

Layout

Similar to all Thai royal palaces of the past Dusit Palace is divided into three areas, the outer, middle and inner courts. However unlike the Grand Palace, Dusit Palaces' courts were organized differently and were separated by canals and gardens as opposed to walls.[1] The king then allocated different residential halls and gardens to his consorts and children. The gardens are connected by gates with names drawn from motifs on blue and white Chinese porcelain ware, which the king picked out himself. The gates were specifically named after human or animal motifs, while the name of the paths were taken from floral motifs.[2]

Main edifices

- Ananta Samakhom Throne Hall

- Amphorn Sathan Residential Hall

- Vimanmek Mansion

- Abhisek Dusit Throne Hall

- Chitralada Royal Villa

Minor edifices

- Suan Si Ruedu Royal Villa

- Suan Hong Royal Villa

- Suan Nok Mai Royal Villa

- Suan Bua Royal Villa

- HRH Princess Bussabun Bua-Phan Residential Hall

- HRH Princess Arun-Wadi Residential Hall

- HRH Princess Puang Soi Sa-ang Residential Hall

- HRH Princess Orathai Thep Kanya Residential Hall

- Krom Luang Vorased Thasuda Residential Hall

- Tamnak Suan Farang Kangsai Residential Hall

- Tamnka Suan Phudtan Residential Hall

- Tamnak Hor Residential Hall

- Paruskawan Mansion

- Suan Kularb Mansion

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dusit Palace. |

References

Bibliography

- Noobanjong, Koompong (2003), Power, Identity, and the Rise of Modern Architecture: From Siam to Thailand, Dissertation.Com, ISBN 0-500-97479-9

External links

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||