Duodenum

| Duodenum | |

|---|---|

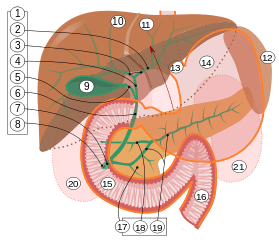

Schematic diagram of the gastrointestinal tract, highlighting the duodenum. | |

| Details | |

| Latin | Intestinum duodenum |

| Precursor | Foregut (1st and 2nd parts), Midgut (3rd and 4th part) |

| Inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery, Superior pancreaticoduodenal artery | |

| Pancreaticoduodenal veins | |

| celiac ganglia, vagus[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

| Gray's | p.1169 |

| MeSH | A03.556.124.684.124 |

| Dorlands /Elsevier | Duodenum |

| TA | A05.6.02.001 |

| FMA | 7206 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

9. Gallbladder, 10–11. Right and left lobes of liver. 12. Spleen.

13. Esophagus. 14. Stomach. Small intestine: 15. Duodenum, 16. Jejunum

17. Pancreas: 18: Accessory pancreatic duct, 19: Pancreatic duct.

20–21: Right and left kidneys (silhouette).

The anterior border of the liver is lifted upwards (brown arrow). Gallbladder with Longitudinal section, pancreas and duodenum with frontal one. Intrahepatic ducts and stomach in transparency.

The duodenum /ˌduːəˈdinəm/ is the first section of the small intestine in most higher vertebrates, including mammals, reptiles, and birds. In fish, the divisions of the small intestine are not as clear, and the terms anterior intestine or proximal intestine may be used instead of duodenum.[2] In mammals the duodenum may be the principal site for iron absorption.[3]

The duodenum precedes the jejunum and ileum and is the shortest part of the small intestine, where most chemical digestion takes place.[4]

In humans, the duodenum is a hollow jointed tube about 25–38 cm (10–15 inches) long connecting the stomach to the jejunum. It begins with the duodenal bulb and ends at the suspensory muscle of duodenum.[5]

Structure

The duodenum is a 25–38 cm C-shaped structure lying adjacent to the stomach. It is divided anatomically into four sections. The first part of the duodenum lies within the peritoneum but its other parts are retroperitoneal.[6] :273

First part

The first part, or superior part, of the duodenum is a continuation from the pylorus. It is superior to the rest of the segments, at the vertebral level of L1. The duodenal cap or ampulla, about 2 cm long, is the very first part of the duodenum and is slightly dilated. The duodenal cap is a remnant of the mesoduodenum, a mesentery which suspends the organ from the posterior abdominal wall in fetal life.[7] The first part of the duodenum is mobile, and connected to the liver by the hepatoduodenal ligament of the lesser omentum. The first part of the duodenum ends at the corner, the superior duodenal flexure.[8]:273

Relations:

- Anterior

- Posterior

- Superior

- Neck of gallbladder

- Hepatoduodenal ligament (lesser omentum)

- Inferior

Second part

The second part, or descending part, of the duodenum begins at the superior duodenal flexure. It goes inferior to the lower border of vertebral body L3, before making a sharp turn medially into the inferior duodenal flexure, the end of the descending part.[8]:274

The pancreatic duct and common bile duct enter the descending duodenum, through the major duodenal papilla. The second part of the duodenum also contains the minor duodenal papilla, the entrance for the accessory pancreatic duct. The junction between the embryological foregut and midgut lies just below the major duodenal papilla.[8]:274

Third part

The third part, or horizontal part or inferior part of the duodenum begins at the inferior duodenal flexure and passes transversely to the left, passing in front of the inferior vena cava, abdominal aorta and the vertebral column. The superior mesenteric artery and vein are anterior to the third part of duodenum.[8]:274 This part may be compressed between Aorta and SMA causing Superior Mesenteric Artery Syndrome

Fourth part

The fourth part, or ascending part, of the duodenum passes upward, joining with the jejunum at the duodenojejunal flexure. The fourth part of the duodenum is at the vertebral level L2, and may pass directly on top of, or slightly left to, the aorta.[8]:274

Blood supply

The duodenum receives arterial blood from two different sources. The transition between these sources is important as it demarcates the foregut from the midgut. Proximal to the 2nd part of the duodenum (approximately at the major duodenal papilla – where the bile duct enters) the arterial supply is from the gastroduodenal artery and its branch the superior pancreaticoduodenal artery. Distal to this point (the midgut) the arterial supply is from the superior mesenteric artery (SMA), and its branch the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery supplies the 3rd and 4th sections. The superior and inferior pancreaticoduodenal arteries (from the gastroduodenal artery and SMA respectively) form an anastomotic loop between the celiac trunk and the SMA; so there is potential for collateral circulation here.

The venous drainage of the duodenum follows the arteries. Ultimately these veins drain into the portal system, either directly or indirectly through the splenic or superior mesenteric vein.

Lymphatic drainage

The lymphatic vessels follow the arteries in a retrograde fashion. The anterior lymphatic vessels drain into the pancreatoduodenal lymph nodes located along the superior and inferior pancreatoduodenal arteries and then into the pyloric lymph nodes (along the gastroduodenal artery). The posterior lymphatic vessels pass posterior to the head of the pancreas and drain into the superior mesenteric lymph nodes. Efferent lymphatic vessels from the duodenal lymph nodes ultimately pass into the celiac lymph nodes.

Histology

Under microscopy, the duodenum has a villous mucosa. This is distinct from the mucosa of the pylorus, which directly joins to the duodenum. Like other structures of the gastrointestinal tract, the duodenum has a mucosa, submucosa, muscularis externa, and adventitia. Glands line the duodenum, known as Brunner's glands, which secrete mucus and bicarbonate in order to neutralise stomach acids. These are distinct glands not found in the ileum or jejunum, the other parts of the small intestine.[9] :274–275

-

Dog Duodenum 100X

-

Duodenum with amyloid deposition in lamina propria

-

Section of duodenum of cat. X 60

-

Micrograph showing giardiasis on a duodenal biopsy (H&E stain)

-

Duodenum with brush border (microvillus)

Function

The duodenum is largely responsible for the breakdown of food in the small intestine, using enzymes. The villi of the duodenum have a leafy-looking appearance, which is a histologically identifiable structure. Brunner's glands, which secrete mucus, are found in the duodenum only. The duodenum wall is composed of a very thin layer of cells that form the muscularis mucosae. The duodenum is almost entirely retroperitoneal. It has three parts and each part has its own significance.

The duodenum also regulates the rate of emptying of the stomach via hormonal pathways. Secretin and cholecystokinin are released from cells in the duodenal epithelium in response to acidic and fatty stimuli present there when the pylorus opens and releases gastric chyme into the duodenum for further digestion. These cause the liver and gall bladder to release bile, and the pancreas to release bicarbonate and digestive enzymes such as trypsin, lipase and amylase into the duodenum as they are needed.

Clinical significance

Ulceration

Ulcers of the duodenum commonly occur because of infection by the bacteria Helicobacter pylori. This bacteria, through a number of mechanisms, erodes the protective mucosa of the duodenum, predisposing it to damage from gastric acids. The first part of the duodenum is the most common location of ulcers as it is where the acidic chyme meets the duodenal mucosa before mixing with the alkaline secretions of the duodenum.[10] Duodenal ulcers may cause recurrent abdominal pain and dyspepsia, and are often investigated using a urea breath test to test for the bacteria, and endoscopy to confirm ulceration and take a biopsy. If managed, these are often managed through antibiotics that aim to eradicate the bacteria, and PPIs and antacids to reduce the gastric acidity.[11]

Coeliac disease

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines specify that a duodenal biopsy is required for the diagnosis of adult coeliac disease. The biopsy is ideally performed at a moment when the patient is on a gluten-containing diet.[12]

Other

Other causes of disease include:

- Inflammation of the duodenum, known as duodenitis.

- Cancer of the duodenum, known as duodenal cancer.

Etymology

The name duodenum is from Medieval Latin, short for intestīnum duodēnum digitōrum, which may be translated: intestine of twelve finger-widths (in length), from Latin duodēnum, genitive pl. of duodēnī, twelve each, from duodecim, twelve.[13] The Latin phrase intestīnum duodēnum digitōrum is thought to be a loan-translation from the Greek word dodekadaktylon (δώδεκαδάκτυλοv), literally "twelve fingers long." The intestinal section was so called by Greek physician Herophilus (c.335–280 B.C.E.) for its length, about equal to the breadth of twelve fingers.[14]

Additional images

-

Sections of the small intestine

-

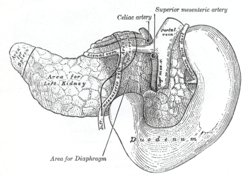

The celiac artery and its branches; the stomach has been raised and the peritoneum removed

-

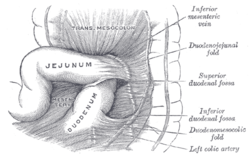

Superior and inferior duodenal fossæ

-

Duodenojejunal fossa

-

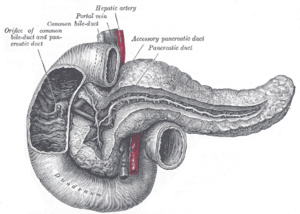

The pancreas and duodenum from behind

-

Transverse section through the middle of the first lumbar vertebra, showing the relations of the pancreas

-

The pancreatic duct

-

Region of pancreas

-

Duodenum

-

Duodenum

-

Duodenum

See also

- This article uses anatomical terminology; for an overview, see anatomical terminology.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Duodenum. |

References

- ↑ Physiology at MCG 6/6ch2/s6ch2_30

- ↑ Guillaume, Jean; Praxis Publishing; Sadasivam Kaushik; Pierre Bergot; Robert Metailler (2001). Nutrition and Feeding of Fish and Crustaceans. Springer. p. 31. ISBN 978-18-5233-241-9. Retrieved 2009-01-09.

- ↑ Latunde-Dada GO; Van der Westhuizen J; Vulpe CD et al. (2002). "Molecular and functional roles of duodenal cytochrome B (Dcytb) in iron metabolism". Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 29 (3): 356–60. doi:10.1006/bcmd.2002.0574. PMID 12547225.

- ↑ "Duodenal Anatomy".

- ↑ van Gijn J; Gijselhart JP (2011). "Treitz and his ligament.". Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 155 (8): A2879. PMID 21557825.

- ↑ Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Singh, Inderbir; GP Pal (2012). "13". Human Embryology (9 ed.). Delhi: Macmillan Publishers India. p. 163. ISBN 9789350591222.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 Drake, Richard L.; Vogl, Wayne; Tibbitts, Adam W.M. Mitchell; illustrations by Richard; Richardson, Paul (2005). Gray's anatomy for students. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2306-0.

- ↑ Deakin, Barbara Young ... [et al.] ; drawings by Philip J. (2006). Wheater's functional histology : a text and colour atlas (5th ed. ed.). [Edinburgh?]: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-4430-6-8508.

- ↑ Smith, Margaret E. The Digestive System.

- ↑ Britton, the editors Nicki R. Colledge, Brian R. Walker, Stuart H. Ralston ; illustrated by Robert (2010). Davidson's principles and practice of medicine. (21st ed. ed.). Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier. pp. 871–874. ISBN 978-0-7020-3085-7.

- ↑ Ludvigsson, J. F.; Bai, J. C.; Biagi, F.; Card, T. R.; Ciacci, C.; Ciclitira, P. J.; Green, P. H. R.; Hadjivassiliou, M.; Holdoway, A.; van Heel, D. A.; Kaukinen, K.; Leffler, D. A.; Leonard, J. N.; Lundin, K. E. A.; McGough, N.; Davidson, M.; Murray, J. A.; Swift, G. L.; Walker, M. M.; Zingone, F.; Sanders, D. S. (2014). "Diagnosis and management of adult coeliac disease: Guidelines from the British Society of Gastroenterology". Gut 63 (8): 1210–1228. doi:10.1136/gutjnl-2013-306578. ISSN 0017-5749.

- ↑ American Heritage Dictionary, 4th edition

- ↑ online etymology: http://www.etymonline.com/index.php?term=duodenum

External links

| Look up duodenum in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- duodenum at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||