Dunvegan Provincial Park

| Dunvegan Provincial Park | |

|---|---|

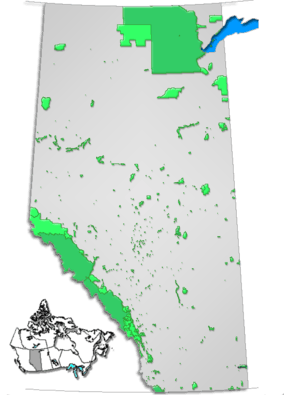

Location of Dunvegan Provincial Park in Alberta | |

| Location | Fairview No. 136, Alberta, Canada |

| Nearest city | Fairview |

| Coordinates | 55°55′25″N 118°35′40″W / 55.92361°N 118.59444°WCoordinates: 55°55′25″N 118°35′40″W / 55.92361°N 118.59444°W |

| Governing body | Alberta Culture |

Dunvegan Provincial Park and Historic Dunvegan are a provincial park and a provincial historic site of Alberta located together on one site. They are located in Dunvegan, at the crossing of Peace River and Highway 2, between Rycroft and Fairview.

The site was the location of one of Alberta's earliest fur trade posts and missionary centres. The location of the original Fort Dunvegan is also a National Historic Site of Canada. It was built in 1805 by Archibald Norman McLeod and named for his family's ancestral home, Dunvegan Castle.

The historic site consists of a visitor centre and some historic buildings manned by historic interpreters. The campground consists of 67 sites with electrical hook ups, a day use area and playground. Dunvegan Provincial Park is jointly managed by the ministries of Alberta Tourism, Parks, and Recreation (the campground) and Alberta Culture (the historic site).

Dunvegan West Wildland Park is an extension of this provincial park.

History

Natural Setting

Dunvegan is located on a flat of land on the north shore of the Peace River at a place where the river extends to its southernmost point in Alberta. The Peace is a relatively new river and indeed is still being formed as can be witnessed by the land slippages regularly occurring along its banks and the bars continually forming along its shores.

The river was created after glaciers from the last ice age began to melt some 15,000 years ago and a vast lake was created, covering virtually all of the Peace River Country. The lake was drained by the river which flows east then north as part of the Mackenzie Basin which empties into the Arctic Ocean.

As the glacial lake receded over the centuries, the river levels dropped. Traces of the shorelines can be detected on the edge of the broad promontory overlooking Dunvegan from the north. Eventually, a number of benches and flats appeared along the river, including the one which came to accommodate Dunvegan.

The flats were covered with huge deposits of alluvial soil which became lush with vegetation and teamed with wildlife. This was noted by Sir Alexander Mackenzie when he passed through on his famous journey to the Pacific Ocean in 1793. After passing near the eventual site of Dunvegan in May, he wrote:

The magnificent theatre of nature has all the decorations which the trees and animals of the country can afford it: groves of poplars in every shape vary the scene; and their intervals are livened with vast herds of elks and buffaloes….. The whole country displayed an exuberant verdure; the trees that bear a blossom were advancing fast to that delightful appearance, and the velvet rind of their branches reflecting the oblique rays of a rising or setting sun, added a splendid gaiety to the scene, which no expressions of mine are qualified to describe.

The First Nations

Mackenzie and his group of nine voyageurs were on the outlook for fur trading possibilities as well as a route to the Pacific. During the winter of 1792-93, the group had camped at Fort Fork, just upriver from the confluence of the Peace and Smoky. Here, they encountered members of the Beaver First Nation and learned much about their culture and some about that of their rivals, the Cree.

The Beaver (Dunne-za) were an Athapaskan (Dene) people who had entered the region from the north over a century earlier. In recent times, they had encountered hostility from bands of Cree coming in from the southeast who were themselves in search of hunting and trading possibilities. According to Mackenzie, the Beaver were:

excellent hunters, and their exercise in that capacity is so violent to reduce them in general to a very meager appearance…. They are more vicious and warlike than the Chipewyan, from which they sprang. Though they do not possess their selfishness … they are liberal and generous [and] remarkable for their honesty…. They are a quiet, lively, active people, with a keen, penetrating dark eye; and though they are very susceptible of anger, they are easily appeased.

Mackenzie and later Euro-Canadian visitors came to regard the Beaver as basically peaceful. Typical was the perspective of Daniel Harmon who stayed at Dunvegan from 1808 to 1810. In his memoir, Harmon described the Beaver as “a peaceable and quiet people and perhaps the most honest of any on the face of the earth.” In the 1840s, trader John McLean depicted them as:

A more diminutive race than the Chippewyan and their features bear a great resemblance to those of the Cree. They are allowed to be generous, hospitable and brave; and are distinguished by their strict adherence to the truth.

fur traders

In 1823, Fort St. John was scheduled to close, ostensibly to keep the Beaver trading at Dunvegan while the rival Sikani would trade at Hudson’s Hope. Apparently upset by this, a group of Beaver massacred trader Guy Hughes and four of his men at Fort St. John. With this, Dunvegan was closed as well as Fort St. John.

In 1828, with peace evidently restored along the Peace River, Dunvegan was reopened and trading continued. Before long, bands of Beaver were joined by Cree and even some incoming Iroquois. A common pattern emerged for bands to come from as far away as Peace River Crossing, Sturgeon Lake, the Grande Prairie, Fort St. John, and the Pouce Coupe Prairie in spring and fall to stock up with goods payable against the fur and meat to be brought in on their return trips.

At Dunvegan, the fur was cured, pressed, and baled for shipment down the river and over to Fort Chipewyan and Fort McMurray. From there, it was shipped east along the Clearwater River, over the Methye Portage, and into the Churchill River system. It eventually arrived at Fort Prince of Wales on Hudson Bay, from where it was shipped to London, England.

During these years, Dunvegan grew into a post with over 40 men, and, in some cases, women. The chief trader was accompanied by several “servants,” most indentured to the Company. Many were ethnically Scottish, but a growing number of Metis were also filling their ranks. In addition, a number of “freemen” were brought in to hunt, trap and undertake freighting for the Company. Most of these were Metis, although certain Cree and Beaver were also directly employed by the Company as Fort hunters.

The Plight of the Beaver

With so much trapping and hunting in the area, the fur-bearing animals began to grow scarce. This brought much hardship to the Native communities, the 1840s being a particularly bad time. In 1842, Chief Trader Francis Butcher wrote the following entries in this journal:

February 8 – Grand Oreilles and a lad arrived, the former nothing but skin and bone that we hardly knew him, he left his family with Casse’s son a short distance the other side of the Clump of Vines, they being too weak to come to the Fort.

February 10th – In the afternoon a poor miserly wretch literally nothing but skin and bone (Raquette’s son-in-law) dragged himself to the Fort and told us he had left his family consisting of twelve individuals a little distance above the hills unable to reach the Fort. Two have already perished. We accordingly sent for them. It is impossible to describe their appearance, for surely such misery is seldom to be seen.

February 15th – Pork Eater’s Son (St. John’s) arrived starving followed by his wife and child. They have left the Old Pork Eater, his second son and Bon a View’s son with their families three days from this unable to move.

February 16th – Arrived after sunset Renard’s second son starving for which his appearance vouches, tells us that Lamalais’ son and the deceased Canada’s wife and family are a short distance from this, but were unable to follow him being too weak.

Starvation was compounded by the arrival of white men’s diseases. Throughout the 19th century, epidemics of influenza, smallpox, measles, whooping cough, scarlet fever and tuberculosis occurred, with countless dying.

With so much illness and hunger, it is not surprising that, by the later 19th century, the Beaver were commonly thought by Euro-Canadian visitors to be a dying race. They would survive however, with many moving westward into British Columbia. Though devastated by the international Spanish Flu epidemic of 1918-19, their population steadily grew in the years that followed, although many came to intermarry with other First Nations.

The Coming of the Missionaries

Expressing special concern for the Beaver around Dunvegan were the Anglican and Roman Catholic missionaries who came to establish churches near the trading post during the latter 19th century. The first Christian missionary to visit the area was actually a Methodist, James Evans, in 1841, but he did not stay. In 1867, an Oblate missionary, Father Christophe Tissier, established the St. Charles Mission on land just east of the trading post.

Tissier’s correspondence reveals the physical and emotional hardships endured by many of the Oblates priests who ventured to wilderness outposts in the Northwest during this time. He stayed however until the mid-1880s and was replaced by several priests, mainly Father Emile Grouard, under whom the mission was refurbished and a new church building and rectory constructed. These buildings, now restored, are a main feature of Historic Dunvegan.

In 1880, the Anglicans established a mission on the west side of the trading post. The first Anglican missionary, Thomas Bunn, was soon replaced by John Gough Brick, and, in 1886, by Alfred Campbell Garrioch whose memoir, A Hatchet Mark In Duplicate, provides a rare glimpse into life around Dunvegan and the Northwest at the time.

Garrioch stayed until 1891, accompanied by his wife, Agnes. Although there are no structural remains of St. Savior’s Mission, the site contains some of the Manitoba maples he brought in, as well as the grave of the Garriochs’ infant daughter, Caroline.

The Later Fur Trade

Garrioch’s departure was hastened, in part, by the decline in the fur trade around Dunvegan. Although the Oblate missionary, Joseph LeTreste, stayed until 1903, the St. Charles Mission was also experiencing dwindling attendance.

The decline in the fur trade had begun in the 1880s, just after Dunvegan had been made headquarters of a Peace River Trading District, serving the posts at Fort St. John, Hudson’s Hope, Fort Vermilion, Battle River, Peace River and Lesser Slave Lake. Among the buildings constructed to the east of the old North West Company site were a fur office, two large warehouses, and a Factor’s House. Constructed in 1878, the Factor’s House is the oldest extant dwelling in northern Alberta and one of the main features of Historic Dunvegan.

In 1878 however, the Hudson’s Bay Company decided to put more resources into the Athabasca and Mackenzie Rivers, with the fur brought down to Fort Edmonton along the Athabasca. The previous ten years had seen much competition on the Peace by independent traders such as the Elmore Brothers, William Cust, Dan Carey, and Henry Fuller “Twelve Foot” Davis who established a post across the river from Dunvegan.

Treaty 8 and its Aftermath

In 1899, Treaty 8 was negotiated with the First Nations of what is now northern Alberta. All people with some element of Aboriginal ancestry were offered Half-breed scrip as an alternative to treaty. This was during the Klondike gold rush when the Dominion government was certain that a flood of settlers would soon be coming into the region.

With the Treaty signings and subsequent adhesions, the government felt safe in encouraging agricultural settlement of the Peace River Country, with some lands set aside as reserves for those Native people who chose treaty as opposed to scrip. To the north of Dunvgean, a large Beaver reserve was subdivided in 1905.

Large-scale settlement of the region was delayed however due to the absence of a railway. When the Alberta government announced lucrative bond guarantees to major railway companies in 1909 to extend lines into the Peace River region, several projects were announced. With this, a Dominion land office was set up at Grouard, townships and quarter-sections were subdivided, and homesteading was begun.

Dunvegan Townsites

The railway which finally did reach the Peace River Country in 1915 was the Edmonton, Dunvegan and British Columbia Railway, owned by John Duncan MacArthur. As the initial file plan called for the line to cross the Peace River at Dunvegan, several entrepreneurs acquired land around the old fur trade site, and even into the surrounding hills and beyond, in order to establish townsites. Certain that the railway would pass through, many investors purchased lots in the townsites, convinced that Dunvegan would become a metropolis.

Soon realizing the virtual impossibility of constructing a bridge across the Peace River at Dunvegan, with its high and wide jagged banks, MacArthur instead pushed his grade from Watino to Spirit River, intending eventually to reach the British Columbia border and beyond. Another line crossed the Peace River at Peace River in 1919. The townsites at Dunvegan remained stillborn, although many investors continued to hold subdivided lots in the area until recent times, some of them even on the hillside.

The Market Gardens

With the townsites in abeyance and the fur trade all but eliminated, the Hudson’s Bay Company trading post, now a commercial store, was finally closed in 1918. This was not the end of commercial productivity for the site however. In 1909, a ferry was installed by the provincial government and it soon proved to be an important link between the north and south Peace River Country, with Alberta Highway #1 (later#2) crossing there. In 1912, the roadway was accompanied by a Dominion telegraph office.

In 1921, the Factor’s House was occupied by Robert and Lily Peters who also acquired the 32 acres around it owned by the Hudson’s Bay Company. They and their children occupied the site until 1943. The Factor’s House served not only as their dwelling, but also as a grocery store, gas station, post office and telephone exchange. The mission site served as a home and repair shop for the ferry operators, the chapel also becoming a general store.

The Peters also cultivated a large garden, which was able to produce lush crops of fruits and vegetables. Agricultural productivity had been a hallmark of Dunvegan since the early 1800s, and indeed was one of the reasons the government felt the Peace River Country would be ideal for farming. Cognizant of this was Mike Marusiak of Rycroft who, in 1946, acquired the Peters property with the idea of establishing a market garden. In time, this became the most productive market garden in northwest Alberta, famous for its corn, cucumbers, other vegetables, and various varieties of fruit, especially strawberries and watermelon.

Dunvegan Historic Site

In the meantime, the property holding St. Charles Mission and Rectory continued to be owned by the Roman Catholic Diocese of Athabasca. Picnics were often held at the site and the Fairview Chapter of the Knights of Columbus began to take care of the Church buildings, eventually turning the Church into a museum. In 1956, they persuaded the provincial government to acquire a portion of the site as a provincial park. The government then began a program of restoration work on the buildings. The area to the west, the old St. Savior’s Mission site, now known as “the Maples,” was also a favourite picnic spot, used mainly by the Anglicans. It eventually became a municipal park, maintained by the Municipal District of Fairview.

In 1960, the provincial government replaced the ferry with a large suspension bridge. In 1978, the Factor’s House was designated a provincial historic resource. In 1984, the government purchased the building and surrounding area, which included the St. Charles Mission and rectory. Land to the east was then made over into a provincially operated campground. In 1994, a Visitor Reception Center was opened, where travelers were encouraged to come during the summer months. The Centre continues to serve visitors and is managed by the Department of Culture with the close co-operation of the Fort Dunvegan Historical Society.

References

David Leonard, Government of Alberta, Heritage Division, Historic Resources Management, 2012

Further reading

Edwards, O.C. On the North Trail. Alberta Records Publication, 1999.

Francis, Daniel and Michael Payne. A Narrative History of Fort Dunvegan. Watson and Dwyer. 1993.

Harmon, Daniel Williams. Sixteen Years in the Indian Country: The Journal of Daniel Williams Harmon, 1800-1816. MacMillan of Canada. 1957.

Leonard, David. Delayed Frontier: The Peace River Country to 1909. Detselig Enterprises. 1995.

Leonard, D.W. and V.L. Lemieux. A Fostered Dream: The Lure of the Peace Country, 1872-1914. Detselig Enterprises. 1992.

MacGregor, J.G. The Land of Twelve Foot Davis: A History of the Peace Country. Applied Art Products. 1952.

Mair, Charles. Through the Mackenzie Basin: An Account of the Signing of Treaty No. 8 and the Scrip Commission, 1899. University of Alberta Press, 1999.