Dumbarton Castle

| Dumbarton Castle | |

|---|---|

|

Dumbarton, Scotland GB grid reference NS399744 | |

|

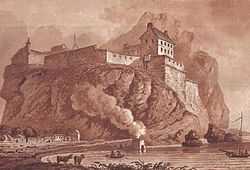

Looking across the River Clyde towards Dumbarton Castle | |

Dumbarton Castle | |

| Coordinates | 55°56′10″N 4°33′46″W / 55.9360°N 4.5628°W |

Dumbarton Castle (Scottish Gaelic: Dùn Breatainn, pronounced [d̪̊unˈb̊ɾʲɛhd̪̊ɪɲ]) has the longest recorded history of any stronghold in Scotland. It overlooks the Scottish town of Dumbarton, and sits on a plug of volcanic basalt known as Dumbarton Rock which is 240 feet (73 m) high.

History

Iron Age

At least as far back as the Iron Age, this has been the site of a strategically important settlement. Its early residents were known to have traded with the Romans. The presence of a settlement is first recorded in a letter Saint Patrick wrote to King Ceretic of Alt Clut in the late 5th century.

Early Medieval Era

Ford has proposed that Dumbarton was the Cair Brithon ("Fort of the Britons") listed by Nennius among the 28 cities of Sub-Roman Britain.[1] From the fifth century until the ninth, the castle was the centre of the independent Scottish Kingdom of Strathclyde. Alt Clut or Alcluith (Scottish Gaelic: Alt Chluaidh, pronounced [aɫ̪d̪̊ˈxɫ̪uəj], lit. "Rock of the Clyde"), the Brythonic name for Dumbarton Rock, became a metonym for kingdom. The king of Dumbarton in about AD 570 was Riderch Hael, who features in Welsh and Latin works.

During his reign Merlin was said to have stayed at Alt Clut. The medieval Scalacronica of Sir Thomas Grey records the legend that "Arthur left Hoël of Little Britain his nephew sick at Alcluit in Scotland."[2] Hoël made a full recovery, but was besieged in the castle by the Scots and Picts. The story first appeared in Geoffrey of Monmouth's Historia Regum Britanniae.[3] Amongst lists of three things, in the triads of the Red Book of Hergest, the third "Unrestrained Ravaging" was Aeddan Fradog (the Wily, perhaps Áedán mac Gabráin), coming to the court of Rhydderch the Generous at Alclud, who left neither food nor drink nor beast alive. This battle also appears in stories of Myrddin Wyllt, the Merlin of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Vita Merlini, perhaps conflated with the battle of Arfderydd, located as Arthuret by some authors.[4]

In 756, the first (and second) losses of Dumbarton Rock were recorded. A joint force of Picts and Northumbrians captured Alcluith after a siege, only to lose it again a few days later. By 870, Dumbarton Rock was home to a tightly packed British settlement, which served as a fortress and as the capital of Alt Clut. The Vikings laid siege to Dumbarton for four months, eventually defeating the inhabitants when they cut off their water supply. The Norse king Olaf returned to the Viking city of Dublin in 871, with two hundred ships full of slaves and looted treasures. Olaf came to an agreement with Constantine I of Scotland, and Artgal of Alt Clut. Strathclyde's independence may have come to an end with the death of Owen the Bald, when the dynasty of Kenneth mac Alpin began to rule the region.

Medieval Era

In medieval Scotland, Dumbarton (Dùn Breatainn, which means "the fortress of the Britons") was an important royal castle. It sheltered David II and his young wife, Joan of The Tower after the Scottish defeat at Halidon Hill in 1333.

In 1425 the castle was attacked by James the Fat, youngest son of Murdoch Stewart, Duke of Albany, who had been imprisoned by King James I of Scotland on charges of treason. James the Fat became a rallying point for enemies of the King, and raised a large rebellion against the crown. He marched on the town of Dumbarton and burned it, but was unable to take the castle, whose defender John Colquhoun successfully held out against James' men. [6] [7]

Patrick Hepburn, 1st Earl of Bothwell, was Captain of Dumbarton castle on 1 April 1495.

Sixteenth century

During the war of the Rough Wooing, the castle was briefly occupied against the Scottish Government of Regent Arran by the Bishop of Caithness, Robert Stewart, a brother of Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox, who came from England with the support of Henry VIII. He had sailed from Chester with around 20 followers in May 1546 in the Katherine Goodman and a pinnace.[8] Having borrowed the artillery of the Earl of Argyle, Arran successfully besieged the castle, which surrendered after 20 days. The chronicle historian John Lesley wrote that the Captain and the Bishop surrendered the castle to Arran and were rewarded, after negotiation by the Earl of Huntly.[9] The siege at Dumbarton delayed Arran's action at the siege of St Andrews Castle on the east coast of Scotland.[10]

In 1548, after the Battle of Pinkie, east of Edinburgh, the infant Mary, Queen of Scots was kept at the castle for several months before her removal to France for safety, where she was soon betrothed to the young dauphin Francis.

In October 1570 during the Marian civil war, John Fleming, 5th Lord Fleming fortified the castle for Mary against the supporters of James VI of Scotland with stones he obtained by demolishing churches and houses in Dumbarton and Cardross.[11] His defence of Dumbarton for Mary was satirized in a ballad printed by Robert Lekprevik in May 1570; The tressoun of Dumbertane.[12] Attributed to Robert Sempill, the ballad describes Fleming's failed ambush of Sir William Drury.[13] The castle was captured by the forces of the Regent (Matthew Stewart, 4th Earl of Lennox) led by Thomas Crawford of Jordanhill and John Cunningham of Drumquhassle in the early hours of 2 April 1571, who used ladders to scale the rock and surprise the garrison.[14]

Seventeenth century

The castle's importance declined after Oliver Cromwell's death in 1658. Due to threats posed by Jacobites and the French in the eighteenth century, Britain built new structures and defences there and continued to garrison the castle until World War II.

Governors and Keepers

Governors

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- John Cunningham, 11th Earl of Glencairn

- 1696: Francis Montgomerie

- 1715: William Cunningham, 12th Earl of Glencairn

- 1764: Archibald Montgomerie, 11th Earl of Eglinton

- 1782: Sir Charles Grey[15]

- 1797: Gerard Lake, 1st Viscount Lake[16]

- 1807: William Loftus

- 1810: Andrew John Drummond[17]

- 30 January 1817: Francis Dundas[18]

- 5 February 1824: George Harris, 1st Baron Harris[19]

- 22 May 1829: Thomas Graham, 1st Baron Lynedoch[20]

Lieutenant-Governors

- This list is incomplete; you can help by expanding it.

- ... Edmonstone

- 1796: Hay Ferrier[21]

- 1799: Samuel Graham[22]

- Ferrier again?

- 15 April 1824: John Vincent[23]

Keepers

- 22 December 1927: Sir George Murray Home Stirling, 9th Baronet[24]

- 4 July 1949: Alexander Patrick Drummond Telfer-Smollett[25]

- 9 May 1955: Sir Angus Edward Malise Bontine Cunninghame Graham[26]

- 12 June 1981: Alastair Stevenson Pearson[27]

- 10 September 1996: Donald David Graeme Hardie[28]

The castle today

Today all visible traces of the Dark-Age Alt Clut, its buildings and defences, have gone. Not much survives from the medieval castle: the 14th-century Portcullis Arch, the foundations of the Wallace Tower, and what may be the foundations of the White Tower. There is a 16th-century guard house, which includes a face which according to legend is "Fause Menteith", who betrayed William Wallace.

Most of the existing structures were built in the 18th century, including the Governor's House, built for John Kennedy, 8th Earl of Cassilis, and fortifications which demonstrated the struggle by military engineers to adapt an intractable site to contemporary defensive needs. The splendid views from the twin summits of the White Tower Crag and the Beak remind us why this rocky outcrop was chosen as 'the fortress of the Britons' centuries ago. [29]

The castle is open on a daily basis during the summer season and Saturday-Wednesday in the winter. Visitors must climb the 557 steps to see the White Tower Crag and other features.

Dumbarton Rock is in state ownership and is legally protected by the Scottish Government as a Scheduled Ancient Monument, to conserve it for future generations. Activities such as rock climbing are forbidden; any change or damage caused is considered a criminal offence.

References

- ↑ Ford, David Nash. "[www.britannia.com/history/ebk/articles/nenniuscities.html The 28 Cities of Britain]" at Britannia. 2000.

- ↑ Leland, John, Collectanea, vol.1 part 2 (1770), p.510. John Leland's note of the Scalachronica: Sir Thomas Grey of Heton, Scalachronica, Edinburgh, (1836), p.318, French: "et lessa Hoel son neuew de la Peteit Bretaigne a Alclud en Escoz maladez."

- ↑ Schultz Albert, ed., Historia Regum Britanniae (1854), pp.125-6

- ↑ Ritson, J., Annals of the Caledonians, Picts, and Scots; and of Strathclyde, Cumberland, Galloway and Murray, (1828), pp.164-5, quoting Humphrey Llwyd

- ↑ Stoddart, John (1800), Remarks on Local Scenery and Manners in Scotland. Pub. Wiliam Miller, London. Facing P. 212.

- ↑ McAndrew, Bruce A., p.5, Scotland's Historic Heraldry Retrieved November 2010

- ↑ Campbell, Alastair, p. 113, A History of Clan Campbell, Volume 2 Retrieved November 2010

- ↑ Dasent, ed., Acts of the Privy Council, 1542-1547, vol.1 (1890), 379

- ↑ Thomson, Thomas, ed., John Lesley's History of Scotland, Bannatyne Club (1830), 190.

- ↑ Accounts of the Lord High Treasurer of Scotland, vol. 8 (1908), lxxx, 453, 465: Letters & Papers Henry VIII, vol.21 part 2 (1910) no.6, Arran to the Pope.

- ↑ Calendar State Papers Scotland, vol. 3, (1903), 383.

- ↑ Calendar of State Papers Scotland, vol. 3, (1903), 177: The tressoun of Dumbarton, 15 May, Robert Lekprevik, Edinburgh, 1570.

- ↑ Cranstoun, James, Satirical Poems of the Reformation, vol. 1 (1892) 170-173, & notes vol. 2 (1893), 113-7.

- ↑ Lang, Andrew (1911). A History of Scotland. W. Blackwood in Edinburgh. pp. 64–68.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 12333. p. 2. 21–24 September 1782.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 14046. p. 896. 16–19 September 1797.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 16396. p. 1222. 14–18 August 1810.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 17217. p. 300. 11 February 1817.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 18001. p. 251. 14 February 1824.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 18588. p. 1192. 26 June 1829.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 13911. p. 674. 9–12 July 1796.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 15199. p. 1116. 29 October–2 November 1799.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 18021. p. 661. 24 April 1824.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 33340. pp. 8243–8244. 23 December 1927.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 38660. p. 3345. 8 July 1949.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 40475. p. 2728. 10 May 1955.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 48669. p. 8904. 3 July 1981.

- ↑ The London Gazette: no. 5456. p. 13346. 8 October 1996.

- ↑ "Historic Scotland Official Souvenir Guide"

External links

- Dumbarton Castle – site information from Historic Scotland

- Clyde Waterfront Heritage, Dumbarton Castle

- www.rampantscotland.com Dumbarton Castle

- Electric Scotland on the castle

- Map of Geoffrey of Monmouth's Britain, including Dumbarton, Siân Echard, University of British Columbia

- Engraving of Dumbarton Castle from the West in 1693 by John Slezer at National Library of Scotland