Duga-3

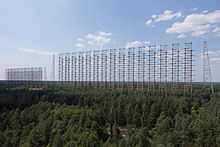

Duga-3 Russian: Дуга-3 (NATO reporting name Steel Yard) was a Soviet over-the-horizon (OTH) radar system used as part of the Soviet ABM early-warning network. The system operated from July 1976 to December 1989. Two Duga-3 radars were deployed, one near Chernobyl and Chernihiv, the other in eastern Siberia.

The Duga-3 systems were extremely powerful, over 10 MW in some cases, and broadcast in the shortwave radio bands. They appeared without warning, sounding like a sharp, repetitive tapping noise at 10 Hz,[1] which led to it being nicknamed by shortwave listeners the Russian Woodpecker. The random frequency hops disrupted legitimate broadcast, amateur radio, commercial aviation communications, utility transmissions, and resulted in thousands of complaints by many countries worldwide. The signal became such a nuisance that some receivers such as amateur radios and televisions actually began including 'Woodpecker Blankers' in their design.

The unclaimed signal was a source for much speculation, giving rise to theories such as Soviet mind control and weather control experiments. However, many experts and amateur radio hobbyists quickly realized it to be an over-the-horizon radar system. NATO military intelligence had already photographed the system and given it the NATO reporting name Steel Yard. This theory was publicly confirmed after the fall of the Soviet Union.

History

Genesis

The Soviets had been working on early warning radar for their anti-ballistic missile systems through the 1960s, but most of these had been line-of-sight systems that were useful for raid analysis and interception only. None of these systems had the capability to provide early warning of a launch, within seconds or minutes of a launch, which would give the defences time to study the attack and plan a response. At the time the Soviet early-warning satellite network was not well developed, and there were questions about their ability to operate in a hostile environment including anti-satellite efforts. An over-the-horizon radar sited in the USSR would not have any of these problems, and work on such a system for this associated role started in the late 1960s.

The first experimental system, Duga-1, was built outside Mykolaiv in Ukraine, successfully detecting rocket launches from Baikonur Cosmodrome at 2,500 kilometers. This was followed by the prototype Duga-2, built on the same site, which was able to track launches from the far east and submarines in the Pacific Ocean as the missiles flew towards Novaya Zemlya. Both of these radar systems were aimed east and were fairly low power, but with the concept proven work began on an operational system. The new Duga-3 systems used a transmitter and receiver separated by about 60 km.[2]

|

|

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Russian Woodpecker

Starting in 1976 a new and powerful radio signal was detected worldwide, and quickly dubbed the Woodpecker by amateur radio operators. Transmission power on some woodpecker transmitters was estimated to be as high as 10 MW equivalent isotropically radiated power.

Triangulation quickly revealed the signals came from Ukraine. Confusion due to small differences in the reports being made from various military sources led to the site being alternately located near Kiev, Minsk, Chernobyl, Gomel or Chernihiv. All of these reports were describing the same deployment, with the transmitter only a few kilometers southwest of Chernobyl (south of Minsk, northwest of Kiev) and the receiver about 50 km northeast of Chernobyl (just west of Chernihiv, south of Gomel). Unknown to civilian observers at the time, NATO was aware of the new installation, which they referred to as Steel Yard.

Civilian identification

Even from the earliest reports it was suspected that the signals were tests of an over-the-horizon radar,[3] and this remained the most popular hypothesis during the Cold War. Several other theories were floated as well, including everything from jamming western broadcasts to submarine communications. The broadcast jamming theory was debunked early on when a monitoring survey showed that Radio Moscow and other pro-Soviet stations were just as badly affected by woodpecker interference as Western stations.

As more information about the signal became available, its purpose as a radar signal became increasingly obvious. In particular, its signal contained a clearly recognizable structure in each pulse, which was eventually identified as a 31-bit pseudo-random binary sequence, with a bit-width of 100 μs resulting in a 3.1 ms pulse.[4] This sequence is usable for a 100 μs chirped pulse amplification system, giving a resolution of 15 km (10 mi) (the distance light travels in 50 μs). When a second Woodpecker appeared, this one located in eastern Russia but also pointed toward the US and covering blank spots in the first system's pattern, this conclusion became inescapable.

In 1988, the Federal Communications Commission conducted a study on the Woodpecker signal. Data analysis showed an inter-pulse period of about 90 ms, a frequency range of 7 to 19 MHz, a bandwidth of 0.02 to 0.8 MHz, and typical transmission time of 7 minutes.

- The signal was observed using three repetition rates: 10 Hz, 16 Hz and 20 Hz.

- The most common rate was 10 Hz, while the 16 Hz and 20 Hz modes were rather rare.

- The pulses transmitted by the woodpecker had a wide bandwidth, typically 40 kHz.

Jamming

To combat this interference, amateur radio operators attempted to "jam" the signal by transmitting synchronized unmodulated continuous wave signals at the same pulse rate as the offending signal. They formed a club called The Russian Woodpecker Hunting Club.[5]

Disappearance

Starting in the late 1980s, even as the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was publishing studies of the signal, the signals became less frequent, and in 1989, they disappeared altogether. Although the reasons for the eventual shutdown of the Duga-3 systems have not been made public, the changing strategic balance with the end of the Cold War in the late 1980s likely had a major part to play. Another factor was the success of the US-KS early-warning satellites, which entered preliminary service in the early 1980s, and by this time had grown into a complete network. The satellite system provides immediate, direct and highly secure warnings, whereas any radar-based system is subject to jamming, and the effectiveness of OTH systems is also subject to atmospheric conditions.

According to some reports, the Komsomolsk-na-Amure installation in the Russian Far East was taken off combat alert duty in November 1989, and some of its equipment was subsequently scrapped. The original Duga-3 site lies within the 30 kilometer Zone of Alienation around the Chernobyl power plant. It appears to have been permanently deactivated, since their continued maintenance did not figure in the negotiations between Russia and Ukraine over the active Dnepr early warning radar systems at Mukachevo and Sevastopol. The antenna still stands, however, and has been used by amateurs as a transmission tower (using their own antennas) and has been extensively photographed.

Locations

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Appearances in media

The Ukrainian-developed computer game S.T.A.L.K.E.R. has a plot focused on the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant and the nuclear accident there. The game heavily features actual locations in the area, including the Duga-3 array. The array itself appears in STALKER: Clear Sky in the city of Limansk-13. While the 'Brain Scorcher' from STALKER: Shadow of Chernobyl was inspired by theories that Duga-3 was used for mind control, it does not take the form of the real array.

In Call of Duty: Black Ops, the Grid map is placed in Pripyat near the DUGA-3 array.

In the movie Divergent, the wall around Chicago is derived from photographs of the Duga-3 array.[6]

The 'Russian woodpecker' appears in Justin Scott's novel The Shipkiller.

The Duga-3 was a prominent focus of the 2015 documentary film, The Russian Woodpecker, by Chad Gracia. In the film there is drone video footage of the view from the top of the array. There is also handheld video footage by the cinematographer, Artem Ryzhykov, climbing to the top and standing on an outstretched platform.[7]

See also

References

- ↑ David L. Wilson (Summer 1985). "The Russian Woodpecker... A Closer Look". Monitoring Times. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Bukharin, Oleg et al. (2001). Pavel Podvig, ed. Russian Strategic Nuclear Forces. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.

- ↑ "Mystery Soviet over-the-horizon tests". Wireless World: 53. February 1977. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ J.P. Martinez (April 1982). "Letter from J. P. Martinez". Wireless World: 89. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Dave Finley (7 July 1982). "Radio hams do battle with 'Russian Woodpecker'". The Miami Herald. Retrieved 2007-06-15.

- ↑ The "Woodpecker" moves to fururistic Chicago! //QRZ.com; The Russian Woodpecker = the wall around Chicago in Divergent; Marcel Birgelen : "thing is surrounded by a great wall, which has some eery similarities to the Russian Woodpecker."

- ↑ The Russian Woodpecker documentary (2015)

Further reading

- Headrick, James M. (1 July 1990). "Looking over the horizon (HF radar)". IEEE Spectrum 27 (7): 36–39. doi:10.1109/6.58421.

- Headrick, James M.; Skolnik, Merrill I. (1 January 1974). "Over-the-Horizon radar in the HF band". Proceedings of the IEEE 62 (6): 664–673. doi:10.1109/PROC.1974.9506.

- Headrick, James M., Ch. 24: "HF over-the-horizon radar," in: Radar Handbook, 2nd ed., Merrill I. Skolnik, ed. [New York: McGraw-Hill, 1990].

- Kosolov, A. A., ed. Fundamentals of Over-the-Horizon Radar (translated by W. F. Barton) [ Norton, Mass.: Artech House, 1987].

- John Pike. "Steel Yard OTH". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved 2010-04-08.

External links

- Chernobyl-2. Secret Military Facility in the territory of exclusion zone. Text and photos 2008

- OTH-Radar "Chornobyl - 2" and Center of space-communication

- "Circle" is an auxiliary system for OTH-Radar "Chornobyl - 2"

- The Russian Woodpecker, Miami Herald, July 1982.

- Steel Yard OTH, globalsecurity.org

- Some pictures of Chernobyl-2

- 'Duga' photos at englishrussia.com

| ||||||||||