Duchy of Thuringia

| Duchy (Landgraviate) of Thuringia | |||||

| Herzogtum (Landgrafschaft) Thüringen | |||||

| Frankish duchy, then State of the Holy Roman Empire | |||||

| |||||

| Capital | Not specified | ||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | ||||

| - | Frankish invasion | c. 531 | |||

| - | Duchy established | 631/32 | |||

| - | Re-established as Landgraviate | 1111/12 | |||

| - | Comital line extinct | 1247 | |||

| - | Split off Hesse | 1264 | |||

| - | To Saxony | 1440 | |||

| - | Division of Altenburg | 1445 | |||

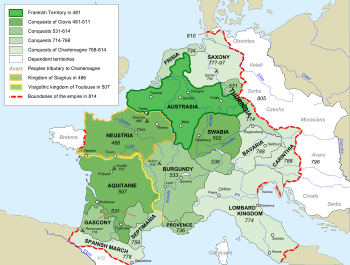

The Duchy of Thuringia was an eastern frontier march of the Merovingian kingdom of Austrasia, established about 631 by King Dagobert I after his troops had been defeated by the forces of the Slavic confederation of Samo at the Battle of Wogastisburg. It was recreated in the Carolingian Empire and its dukes appointed by the king until it was absorbed by the Saxon dukes in 908. From about 1111/12 the territory was ruled by the Landgraves of Thuringia as Princes of the Holy Roman Empire.

History

The former kingdom of the Thuringii arose during the Migration Period after the decline of the Hunnic Empire in Central Europe in the mid 5th century, culminating in their defeat in the 454 Battle of Nedao. With Bisinus a first Thuringian king is documented about 500, who ruled over extended estates that stretched beyond the Main River in the south. His son and successor Hermanafrid married Amalaberga, a niece of the Ostrogoth king Theoderic the Great, thereby hedging the threat of incursions by the Merovingian Franks in the west. However, when King Theoderic died in 526, they took the occasion to invade the Thuringian lands and finally carried off the victory in a 531 battle on the Unstrut River. King Theuderic of Rheims had Hermanafrid trapped in Zülpich (Tolbiacum) where the last Thuringian king was killed. His niece Princess Radegund was kidnapped by King Chlothar I and died in exile in 586.

The Thuringian realm was shattered: the territory north of the Harz mountain range was settled by Saxon tribes, while the Franks moved into the southern parts on the Main River. The estates east of the Saale River were beyond Frankish control and taken over by Polabian Slavs.

Merovingian duchy

The first documented duke (dux) of remaining Thuringia was a local noble named Radulf, installed by King Dagobert in the early 630s. Radulf was able to secure the Frankish border along the Saale River in the east from Slavic incursions. However, according to the Chronicle of Fredegar, in 641/2 his victories "turned his head" (i.e., made him proud) and he allied with Samo and rebelled against Dagobert's successor, King Sigebert III, even going so far as to declare himself king (rex) of Thuringia.[1][2] A punitive expedition led by the Frankish Mayor of the Palace Grimoald ultimatively failed and Radulf was able to maintain his semi-autonomous position. His successors of the local ducal dynasty, the Hedenen, supported missionary activity within the duchy, but seem to have lost their hold on Thuringia after the rise of the Pippinids in the early eighth century. A conflict with Charles Martel around 717–19 brought an end to autonomy.[3]

In 849, the eastern part of Thuringia was organised as the limes Sorabicus, or Sorbian March, and placed under a duke named Thachulf. In the Annals of Fulda his title is dux Sorabici limitis, "duke of the Sorbian frontier", but he and his successors were commonly known as duces Thuringorum, "dukes of the Thuringians", as they set about establishing their power over the old duchy.[4] After Thachulf's death in 873, the Sorbs rose in revolt and he was succeeded by his son Radulf. In 880, King Louis replaced Radulf with Poppo, perhaps a kinsman. Poppo instigated a war with Saxony in 882 and in 883 he and his brother Egino fought a civil war for control of Thuringia, in which the latter was victorious.[5] Egino died in 886 and Poppo resumed command. In 892, King Arnulf replaced Poppo with Conrad. This was an act of patronage by the king, for Conrad's house, the Conradines, were soon feuding with Poppo's, the Babenbergs. But Conrad's rule was short, perhaps because he had a lack of local support.[6] He was replaced by Burchard, whose title in 903 was marchio Thuringionum, "margrave of the Thuringians". Burchard had to defend Thuringia from the incursions of the Magyars and was defeated and killed in battle, along with the former duke Egino, on 3 August 908.[7][8] He was the last recorded duke of Thuringia. The duchy was the smallest of the so-called "younger stem duchies", and was absorbed by Saxony after Burchard's death,[9] when Burchard's sons were finally expelled by Duke Henry the Fowler in 913. The Thuringians remained a distinct people, and in the Middle Ages their land was organised as a landgraviate.[10]

Landgraviate

A separate Thuringian stem duchy did not exist during the emergence of the German kingdom from East Francia in the 10th century. Large parts of the Thuringian estates were controlled by the Counts of Weimar and the Margraves of Meissen. According to the medieval chronicler Thietmar of Merseburg, Margrave Eckard I (d. 1002) was appointed Thuringian duke. After his assassination 1002, Count William II of Weimar acted as Thuringian spokesman with King Henry II of Germany. In 1111/12 Count Herman I of Winzenburg is documented as a Thuringian landgrave, the first mention of a secession from Saxony, however, he later had to yield as he sided with the Papacy during the Investiture Controversy.

Meanwhile the Franconian aristocrat Louis the Springer (1042–1123) laid the foundations for the erection of Wartburg Castle, which became the residence of his descendants who, beginning with his son Louis I, served as Thuringian landgraves. Louis I had married the Rhenish Franconian countess Hedwig of Gudensberg and became the heir of extended estates in Thuringia and Hesse. A close ally of King Lothair II of Germany against the rising Hohenstaufen dynasty, he was appointed Landgrave of Thuringia in 1131. The dynasty maintained the landgraviate throughout the fierce struggle of the Hohenstaufen and Welf royal families, occasionally switching sides according to the circumstances.

Beside the Wartburg, the Ludowingian landgraves had further lavish residences erected, like Neuenburg Castle ("New Castle") near Freyburg, or Marburg Castle in their Hessian estates. In the "Golden Age" under Hohenstaufen rule, Thuringia became a centre of Middle High German culture, epitomized by the legendary Sängerkrieg at the Wartburg, or the ministry of Saint Elizabeth, the daughter of King Andrew II of Hungary. When Landgrave Louis IV married her in 1221, the Ludowingian dynasty had accomplished the advancement to one of the mightiest princely houses of the Holy Roman Empire. Under the rule of the landgraves town privileges were conferred to Mühlhausen and Nordhausen which became Free imperial cities, while the largest city Erfurt remained a possession of the Prince-Archbishops of Mainz. The landgraves maintained close ties with the Teutonic Knights, the order established several commandries east of the Saale, as in Altenburg and Schleiz, with the administrative seat of the Thuringian bailiwick in Zwätzen near Jena.

The last Thuringian landgrave Henry Raspe reached his appointment as German governor by the Hohenstaufen emperor Frederick II in 1242. However, when Frederick was declared deposed by Pope Innocent IV in 1246, he secured the support by the archbishops Siegfried III of Mainz and Conrad of Cologne and had himself elected German anti-king. Mocked as rex clericorum his rule remained disputed, though he was able to defeat the troops of Frederick's son Conrad IV he died one year later. His heritage was claimed by both the Wettin margrave Henry III of Meissen, son of Judith of Thuringia, and Duchess Sophie of Brabant, daughter of late Landgrave Louis IV - a conflict that led to the War of the Thuringian Succession.

As a result, Henry of Meissen gained the bulk of Thuringia in 1264, while the Hessian possessions of the landgraves was separated as the Landgraviate of Hesse under the rule of Sophie's son Henry I. The Meissen margraves of the Wettin dynasty retained the landgravial title. Upon the death of Margrave Frederick III of Meissen his younger brothers divided their heritage in the 1382 Division of Chemnitz, whereby Thuringia passed to Balthasar. Upon the death of Landgrave Frederick IV in 1440, Thuringia fell to his nephew Elector Frederick II of Saxony, the inheritance conflict with his brother William III led to the 1445 Division of Altenburg and the Saxon Fratricidal War over the Wettin lands. The Thuringian lands fell to William III, when he died childless in 1482, Elector Ernest, inherited the landgraviate, uniting the Wettin lands under his rule. After the 1485 Treaty of Leipzig, Thuringia split into the Saxon Ernestine and Albertine duchies.

Rulers

Dukes

- "Older" stem duchy

- 632–642 Radulf (I)

- 642–687 Heden I

- 687–689 Gozbert

- 689–719 Heden II

- "Younger" stem duchy

- 849–873 Thachulf

- 874–880 Radulf (II)

- 880–892 Poppo

- 882–886 Egino (in opposition)

- 892–906 Conrad

- 907–908 Burchard

Landgraves

- 1111/12 Herman of Winzenburg

- Ludowingians

- 1131–1140 Louis I

- 1140–1172 Louis II

- 1172–1190 Louis III

- 1190–1217 Hermann I

- 1217–1227 Louis IV

- 1227–1241 Hermann II

- 1241–1247 Henry Raspe

- 1247–1265 Henry III, Margrave of Meissen

- 1265–1294 Albert II, Margrave of Meissen 1288–1292

purchased by King Adolph of Germany 1294–1298

- 1298–1323 Frederick I, Margrave of Meissen, jointly with his brother

- 1298–1307 Theodoric IV, Landgrave of Lusatia

- 1323–1349 Frederick II, Margrave of Meissen

- 1349–1381 Frederick III, jointly with his brothers

- 1406–1440 Frederick IV

Notes

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy (1991). Germany in the Early Middle Ages, 800–1056. New York: Longman. p. 55. ISBN 0582081564.

- ↑ Curta, Florin (2001). The Making of the Slavs: History and Archaeology of the Lower Danube Region, ca. 500–700. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61, 109. ISBN 0521802024.

- ↑ Wood, Ian (2000). "Before or After Mission: Social Relations across the Middle and Lower Rhine in the Seventh and Eighth Centuries". In Hansen, Inge Lyse; Wickham, Chris. The Long Eighth Century: Production, Distribution and Demand. Leiden: Brill. pp. 149–166. ISBN 9004117237.

- ↑ Reuter, Timothy, ed. (1992). The Annals of Fulda. Manchester Medieval Series, Ninth-Century Histories, vol. II. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 0719034574.

- ↑ Reuter, Annals of Fulda, s. a. 882 and 883.

- ↑ Reuter, Germany in the Early Middle Ages, 123.

- ↑ Reuter, Germany in the Early Middle Ages, 129.

- ↑ Santosuosso, Antonio (2004). Barbarians, Marauders, and Infidels: The Ways of Medieval Warfare. New York: MJF Books. p. 148. ISBN 0813391539.

- ↑ Mitchell, Otis C. (1985). Two German Crowns: Monarchy and Empire in Medieval Germany. Bristol, IN: Wyndham Hall Press. p. 90. ISBN 0932269664.

- ↑ Reuter, Germany in the Early Middle Ages, 133.

Further reading

- Gerd Tellenbach. Königtum und Stämme in der Werdezeit des Deutschen Reiches. Quellen und Studien zur Verfassungsgeschichte des Deutschen Reiches in Mittelalter und Neuzeit, vol. 7, pt. 4. Weimar, 1939.