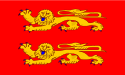

Duchy of Normandy

| Duchy of Normandy | ||||||

| Duché de Normandie | ||||||

| Vassal of West Francia then of the Kingdom of France | ||||||

| ||||||

| ||||||

Normandy's historical borders in the northwest of modern-day France and the Channel Islands | ||||||

| Capital | Rouen | |||||

| Languages | Latin Norman French | |||||

| Religion | Roman Catholicism | |||||

| Government | Feudal monarchy | |||||

| Duke of Normandy | ||||||

| - | 911–927 | Rollo | ||||

| - | 1035–1087 | William the Conqueror | ||||

| - | 1144–1150 | Geoffrey Plantagenet | ||||

| - | 1216–1259 | Henry III | ||||

| Historical era | Middle Ages | |||||

| - | Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte | 911 | ||||

| - | Conquest of England | 1066–1071 | ||||

| - | Conquered by Anjou | 1144 | ||||

| - | Conquered by the French Crown | 1204 | ||||

| - | Treaty of Paris | 1259 | ||||

| - | nominal ducal title abolished | 1790 | ||||

| Today part of | | |||||

The Duchy of Normandy grew out the 911 treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and Rollo, leader of the Vikings, known as Northmen, or Nortmanni in Latin. The duchy was established under Richard II in c. 996. From 1035 to 1135 it was held by the Norman kings of England and then, after 15 years of government by Stephen of Blois and Geoffrey Plantagenet, it was then held by the Angevin kings of England from 1150 to 1204. Normandy was conquered by Philip II of France in 1204 and remained disputed territory until the Treaty of Paris of 1259, when the English sovereigns ceded their claim, except for the Channel Islands.

The title of "Duke of Normandy" was then sporadically conferred in the kingdom of France, the last one having been Louis XVII of France from 1785 to 1789.

Early history

Normandy grew out of various invasions of West Francia by Danish, Norwegian, Hiberno-Norse, Orkney Viking, and Anglo-Danish in the 9th century. Normandy began in 911 as a fief, probably a county (in the sense that it was held by a count), established in 911 by the treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III and a Viking leader, Rollo.

Originally coterminous with the ecclesiastical province of Rouen that was centred on Rouen on the Seine and composed of the northern portion of the province of Neustria, Normandy was later expanded by Rollo's and William Longsword's conquests westward into recent Breton territories (Cotentin and probably Avranchin) and southward to include the areas of Évreux and Alençon. They did it first of all in order to unify politically the Viking settlements of the Seine maritime (Rouen) together with those of the Cotentin, but also to allow the return of the Rouen archbishop in the historical borders of his archbishopric. Eventually the County roughly corresponded to the present-day regions of Upper and Lower Normandy of modern France.

When the Norse ("Norman") settlers spread out over the lands of the Duchy, they married local women and adopted the Gallo-Romance speech of the existing population — much as Normans later adopted the speech of the English after they invaded. In Normandy, the new Norman language formed by the interaction of peoples inherited vocabulary from Norse or Old Danish.

Normandy was formed from Rouen county, the Pays de Caux, and Talou in Dieppe county, which the Vikings had colonised. The capital was established at Rouen in 912, and a western capital was later established at Caen as the Duchy expanded. In 928, Évreux, Hiémois county, and the Bessin were added. In 931–934, Rollo's son William Longsword added the Cotentin Peninsula and the Avranchin. The Channel Islands were added in 933. Sometime around 950–956, Normandy or its frontier became a marchio, according to K.F. Werner.

Norman duchy

Richard II was the first to be styled duke of Normandy (the ducal title became established between 987–1006).

The Norman dukes created the most powerful, consolidated duchy in Western Europe between the years 980, when the dukes helped place Hugh Capet on the French throne, and 1050, despite being part of the Kingdom of France.[1] Scholarly churchmen were brought into Normandy from the Rhineland, and they built and endowed monasteries and supported monastic schools. The dukes imposed heavy feudal burdens on the ecclesiastical fiefs, which supplied the armed knights that enabled the dukes to control the restive lay lords but whose bastards could not inherit. By the mid-11th century the Duke of Normandy could count on more than 300 armed and mounted knights from his ecclesiastical vassals alone.[2] By the 1020s the dukes were able to impose vassalage on the lay nobility as well. Until Richard II, the Norman rulers did not hesitate to call Viking mercenaries for help to get rid of their enemies around Normandy, such as the king of the Francs himself. Olaf Haraldsson crossed the channel in such circumstances to support Richard II in the conflict against the count of Chartres and was baptized in Rouen in 1014.

In 1066, Duke William defeated Harold II of England at the Battle of Hastings and was subsequently crowned King of England, through the Norman conquest of England. Anglo-Norman and French relations became complicated after the Norman Conquest. The Norman dukes retained control of their holdings in Normandy as vassals owing fealty to the King of France, but they were his equals as kings of England. From 1154 until 1214, with the creation of the Angevin Empire, the Angevin kings of England controlled half of France and all of England, dwarfing the power of the French king, yet the Angevins were still technically French vassals.

One interpretation of the Conquest maintains that England became a cultural and economic backwater for almost 150 years after the Norman Conquest, as the kings of England preferred to rule from cities in Normandy, such as Rouen, and to concentrate on their more lucrative continental holdings. Another interpretation holds that Norman Duke-Kings neglected their continental territories, where they in theory owed fealty to the Kings of France, in favour of consolidating their power in their new sovereign realm of England. The resources poured into the construction of cathedrals, castles, and administration of the new realm arguably diverted energy and focus away from the need to defend Normandy, alienating the local nobility and weakening Norman control over the borders of its territory, while at the same time the power of the Kings of France was growing.

The Duchy remained part of the Anglo-Norman realm until 1204, when Philip II of France conquered the continental lands of the Duchy, which became part of the royal demesne. The English sovereigns continued to claim them until the Treaty of Paris (1259) but in fact kept only the Channel Islands. Having little confidence in the loyalty of the Normans, Philip installed French administrators and built a powerful fortress, the Château de Rouen, as a symbol of royal power.

Later history

Although within the royal demesne, Normandy retained some specificity. Norman law continued to serve as the basis for court decisions. In 1315, faced with the constant encroachments of royal power on the liberties of Normandy, the barons and towns pressed the Norman Charter on the king. This document did not provide autonomy to the province but protected it against arbitrary royal acts. The judgments of the Exchequer, the main court of Normandy, were declared final. This meant that Paris could not reverse a judgement of Rouen. Another important concession was that the King of France could not raise a new tax without the consent of the Normans. However the charter, granted at a time when royal authority was faltering, was violated several times thereafter when the monarchy had regained its power.

The Duchy of Normandy survived mainly by the intermittent installation of a duke. In practice, the King of France sometimes gave that portion of his kingdom to a close member of his family, who then did homage to the king. Philippe VI made Jean, his eldest son and heir to his throne, the Duke of Normandy. In turn, Jean II appointed his heir, Charles, who was also known by his title of Dauphin.

In 1465, Louis XI was forced by his nobles to cede the duchy to his eighteen-year-old brother Charles, as an appanage. This concession was a problem for the king since Charles was the puppet of the king's enemies. Normandy could thus serve as a basis for rebellion against the royal power. Louis XI therefore agreed with his brother to exchange Normandy for the Duchy of Guyenne (Aquitaine). Finally, to signify that Normandy would not be ceded again, on 9 November 1469 the ducal ring was placed on an anvil and smashed. This was the definitive end of the duchy on the continent.

Dauphin Louis Charles, the second son of Louis XVI, was again given the nominal title of 'Duke of Normandy' before the death of his elder brother in 1789.

See also

- Duke of Normandy

- Angevin Empire

- Anglo-Norman

- Norman architecture

- History of Normandy

- Gesta Normannorum Ducum

- Roman de Rou

- Treaty of Louviers