Doubly special relativity

Doubly special relativity (DSR) – also called deformed special relativity or, by some, extra-special relativity – is a modified theory of special relativity in which there is not only an observer-independent maximum velocity (the speed of light), but an observer-independent maximum energy scale and minimum length scale (the Planck energy and Planck length).[1]

History

First attempts to modify special relativity by introducing an observer independent length were made by Pavlopoulos (1967), who estimated this length at about 10−15 metres.[2][3] In the context of quantum gravity, Giovanni Amelino-Camelia (2000) introduced what now is called doubly special relativity, by proposing a specific realization of preserving invariance of the Planck length 16.162×10−36 m.[4][5] This was reformulated by Kowalski-Glikman (2001) in terms of an observer independent Planck mass.[6] A different model, inspired by that of Amelino-Camelia, was proposed in 2001 by João Magueijo and Lee Smolin, who also focused on the invariance of Planck energy.[7][8] It was realized that there are indeed three kind of deformations of special relativity that allow one to achieve an invariance of the Planck energy, either as a maximum energy, as a maximal momentum, or both. DSR models are possibly related to loop quantum gravity in 2+1 dimensions (two space, one time), and it has been conjectured that a relation also exists in 3+1 dimensions.[9][10]

The motivation to these proposals is mainly theoretical, based on the following observation: The Planck energy is expected to play a fundamental role in a theory of quantum gravity, setting the scale at which quantum gravity effects cannot be neglected and new phenomena might become important. If special relativity is to hold up exactly to this scale, different observers would observe quantum gravity effects at different scales, due to the Lorentz–FitzGerald contraction, in contradiction to the principle that all inertial observers should be able to describe phenomena by the same physical laws. This motivation has been criticized on the grounds that the result of a Lorentz transformation does not itself constitute an observable phenomenon.[11] DSR also suffers from several inconsistencies in formulation that have yet to be resolved.[12][13] Most notably it is difficult to recover the standard transformation behavior for macroscopic bodies, known as the soccer-ball-problem. The other conceptual difficulty is that DSR is a priori formulated in momentum space. There is as yet no consistent formulation of the model in position space.

There are many other Lorentz violating models in which, contrary to DSR, the principle of relativity and Lorentz invariance is violated by introducing preferred frame effects. Examples are the effective field theory of Sidney Coleman and Sheldon Lee Glashow, and especially the Standard-Model Extension which provides a general framework for Lorentz violations. These models are capable of giving precise predictions in order to assess possible Lorentz violation, and thus are widely used in analyzing experiments concerning the standard model and special relativity (see Modern searches for Lorentz violation).

Main

In principle, it seems difficult to incorporate an invariant length magnitude in a theory which preserves Lorentz invariance due to Lorentz–FitzGerald contraction, but in the same way that special relativity incorporates an invariant velocity by modifying the high-velocity behavior of Galilean transformations, DSR modifies Lorentz transformations at small distances (large energies) in such a way to admit a length invariant scale without destroying the principle of relativity. The postulates on which DSR theories are constructed are:

- The principle of relativity holds, i.e. equivalence of all inertial observers.

- There are two observer-independent scales: the speed of light, c, and a length (energy) scale

(

( ) in such a way that when λ → 0 (η → ∞), special relativity is recovered.

) in such a way that when λ → 0 (η → ∞), special relativity is recovered.

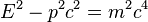

As noted by Jerzy Kowalski-Glikman, an immediate consequence of these postulates is that the symmetry group of DSR theories must be ten-dimensional, corresponding to boosts, rotations and translations in 4 dimensions. Translations, however, cannot be the usual Poincaré generators as it would be in contradiction with postulate 2). As translation operators are expected to be modified, the usual dispersion relation

is expected to be modified and, indeed, the presence of an energy scale, namely  , allows introducing

, allows introducing  -suppressed terms of higher order in the dispersion relation. These higher momenta powers in the dispersion relation can be traced back as having their origin in higher-dimensional (i.e. non-renormalizable) terms in the Lagrangian.

-suppressed terms of higher order in the dispersion relation. These higher momenta powers in the dispersion relation can be traced back as having their origin in higher-dimensional (i.e. non-renormalizable) terms in the Lagrangian.

It was soon realized that by deforming the Poincaré (i.e. translation) sector of the Poincaré algebra, consistent DSR theories can be constructed. In accordance with postulate 1), the Lorentz sector of the algebra is not modified, but just non-linearly realized in their action on momenta coordinates. More precisely, the Lorentz Algebra

remains unmodified, while the most general modification on its action on momenta is

where A, B, C and D are arbitrary functions of  and M,N are the rotation generators and boost generators, respectively. It can be shown that C must be zero and in order to satisfy the Jacobi identity, A, B and D must satisfy a non-linear first order differential equation. It was also shown by Kowalski-Glikman that these constraints are automatically satisfied by requiring that the boost and rotation generators N and M, act as usual on some coordinates

and M,N are the rotation generators and boost generators, respectively. It can be shown that C must be zero and in order to satisfy the Jacobi identity, A, B and D must satisfy a non-linear first order differential equation. It was also shown by Kowalski-Glikman that these constraints are automatically satisfied by requiring that the boost and rotation generators N and M, act as usual on some coordinates  (A=0,...,4) that satisfy

(A=0,...,4) that satisfy

i.e. that belong to de Sitter space. The physical momenta  are identified as coordinates in this space, i.e.

are identified as coordinates in this space, i.e.

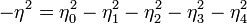

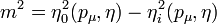

and the dispersion relation that these momenta satisfy is given by the invariant

.

.

This way, different choices for the "physical momenta coordinates" in this space give rise to different modified dispersion relations, a corresponding modified Poincaré algebra in the Poincaré sector and a preserved underlying Lorentz invariance.

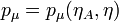

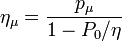

One of the most common examples is the so-called Magueijo–Smolin basis (Also known as the DSR2 model), in which:

which implies, for instance,

![[N_i,P_0]=iP_i\left(1-\frac{P_0}{\eta}\right)](../I/m/7916362e71f06831c120e486b500d3b6.png) ,

,

showing explicitly the existence of the invariant energy scale  as

as ![[N_i,P_0=\eta]=0](../I/m/d77216b07b596bbf76d7f3e6351d80cc.png) .

.

The theory was highly speculative as of first publishing in 2002, as it relies on no experimental evidence so far. It would be fair to say that DSR is not considered a promising approach by a majority of members of the high-energy physics community, as it lacks experimental evidence and there's so far no guiding principle in the choice for the particular DSR model (i.e. basis in momenta de Sitter space) that should be realized in nature, if any.

DSR is based upon a generalization of symmetry to quantum groups. The Poincaré symmetry of ordinary special relativity is deformed into some noncommutative symmetry and Minkowski space is deformed into some noncommutative space. As explained before, this theory is not a violation of Poincaré symmetry as much as a deformation of it and there is an exact de Sitter symmetry. This deformation is scale dependent in the sense that the deformation is huge at the Planck scale but negligible at much larger length scales. It's been argued that models which are significantly Lorentz violating at the Planck scale are also significantly Lorentz violating in the infrared limit because of radiative corrections, unless a highly unnatural fine-tuning mechanism is implemented. Without any exact Lorentz symmetry to protect them, such Lorentz violating terms will be generated with abandon by quantum corrections. However, DSR models do not succumb to this difficulty since the deformed symmetry is exact and will protect the theory from unwanted radiative corrections — assuming the absence of quantum anomalies. Furthermore, models where a privileged rest frame exists can escape this difficulty due to other mechanisms.

Jafari and Shariati have constructed canonical transformations that relate both the doubly special relativity theories of Amelino-Camelia and of Magueijo and Smolin to ordinary special relativity. They claim that doubly special relativity is therefore only a complicated set of coordinates for an old and simple theory. However, the momentum space in deformed special relativity is curved, which is a statement independent of the choice of coordinates. The argument that deformed special relativity is equivalent to special relativity resurfaces on occasion but is widely known to be wrong. The error in the argument comes about because they are based on an incomplete specification of the structure of phase-space.

Predictions

Experiments to date have not observed contradictions to special relativity (see Modern searches for Lorentz violation).

It was initially speculated that ordinary special relativity and doubly special relativity would make distinct physical predictions in high energy processes, and in particular the derivation of the Greisen–Zatsepin–Kuzmin limit would not be valid. However, it is now established that standard doubly special relativity does not predict any suppression of the GZK cutoff, contrary to the models where an absolute local rest frame exists, such as effective field theories like the Standard-Model Extension.

Since DSR generically (though not necessarily) implies an energy-dependence of the speed of light, it has further been predicted that, if there are modifications to first order in energy over the Planck mass, this energy-dependence would be observable in high energetic photons reaching Earth from distant gamma ray bursts. Depending on whether the now energy-dependent speed of light increases or decreases with energy (a model-dependent feature) highly energetic photons would be faster or slower than the lower energetic ones .[14] However, the Fermi-LAT experiment in 2009 measured a 31 GeV photon, which nearly simultaneously arrived with other photons from the same burst, which excluded such dispersion effects even above the Planck energy.[15] It has moreover been argued, that DSR with an energy-dependent speed of light is inconsistent and first order effects are ruled out already because they would lead to non-local particle interactions that would long have been observed in particle physics experiments.[16]

de Sitter relativity

Since the de Sitter group naturally incorporates an invariant length parameter, de Sitter relativity can be interpreted as an example of doubly special relativity, because de Sitter spacetime incorporates invariant velocity, as well as length parameter. There is a fundamental difference, though: whereas in all doubly special relativity models the Lorentz symmetry is violated, in de Sitter relativity it remains as a physical symmetry. A drawback of the usual doubly special relativity models is that they are valid only at the energy scales where ordinary special relativity is supposed to break down, giving rise to a patchwork relativity. On the other hand, de Sitter relativity is found to be invariant under a simultaneous re-scaling of mass, energy and momentum, and is consequently valid at all energy scales.

In-line notes and references

- ↑ Amelino-Camelia, G. (2010). "Doubly-Special Relativity: Facts, Myths and Some Key Open Issues". Symmetry 2: 230–271. arXiv:1003.3942. Bibcode:2010arXiv1003.3942A. doi:10.3390/sym2010230.

- ↑ Pavlopoulos, T. G. (1967). "Breakdown of Lorentz Invariance". Physical Review 159 (5): 1106–1110. Bibcode:1967PhRv..159.1106P. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.159.1106.

- ↑ Pavlopoulos, T. G. (2005). "Are we observing Lorentz violation in gamma ray bursts?". Physics Letters B 625 (1-2): 13–18. arXiv:astro-ph/0508294. Bibcode:2005PhLB..625...13P. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.08.064.

- ↑ Amelino-Camelia, G. (2001). "Testable scenario for relativity with minimum length". Physics Letters B 510 (1-4): 255–263. arXiv:hep-th/0012238. Bibcode:2001PhLB..510..255A. doi:10.1016/S0370-2693(01)00506-8.

- ↑ Amelino-Camelia, G. (2002). "Relativity in space–times with short-distance structure governed by an observer-independent (Planckian) length scale". International Journal of Modern Physics D 11 (01): 35–59. arXiv:gr-qc/0012051. Bibcode:2002IJMPD..11...35A. doi:10.1142/S0218271802001330.

- ↑ Kowalski-Glikman, J. (2001). "Observer-independent quantum of mass". Physics Letters A 286 (6): 391–394. arXiv:hep-th/0102098. Bibcode:2001PhLA..286..391K. doi:10.1016/S0375-9601(01)00465-0.

- ↑ Magueijo, J.; Smolin, L (2001). "Lorentz invariance with an invariant energy scale". Physical Review Letters 88 (19): 190403. arXiv:hep-th/0112090. Bibcode:2002PhRvL..88s0403M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.88.190403.

- ↑ Magueijo, J.; Smolin, L (2003). "Generalized Lorentz invariance with an invariant energy scale". Physical Review D 67 (4): 044017. arXiv:gr-qc/0207085. Bibcode:2003PhRvD..67d4017M. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.67.044017.

- ↑ Amelino-Camelia, Giovanni; Smolin, Lee; Starodubtsev, Artem (2004). "Quantum symmetry, the cosmological constant and Planck-scale phenomenology". Classical and Quantum Gravity 21 (13): 3095–3110. arXiv:hep-th/0306134. Bibcode:2004CQGra..21.3095A. doi:10.1088/0264-9381/21/13/002.

- ↑ Freidel, Laurent; Kowalski-Glikman, Jerzy; Smolin, Lee (2004). "2+1 gravity and doubly special relativity". Physical Review D 69 (4): 044001. arXiv:hep-th/0307085. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..69d4001F. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.69.044001.

- ↑ Hossenfelder, S. (2006). "Interpretation of Quantum Field Theories with a Minimal Length Scale". Physical Review D 73: 105013. arXiv:hep-th/0603032. Bibcode:2006PhRvD..73j5013H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.73.105013.

- ↑ Aloisio, R.; Galante, A.; Grillo, A.F.; Luzio, E.; Mendez, F. (2004). "Approaching Space Time Through Velocity in Doubly Special Relativity". Physical Review D 70: 125012. arXiv:gr-qc/0410020. Bibcode:2004PhRvD..70l5012A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.70.125012.

- ↑ Aloisio, R.; Galante, A.; Grillo, A.F.; Luzio, E.; Mendez, F. (2005). "A note on DSR-like approach to space–time". Physics Letters B 610: 101–106. arXiv:gr-qc/0501079. Bibcode:2005PhLB..610..101A. doi:10.1016/j.physletb.2005.01.090.

- ↑ Amelino-Camelia, G.; Smolin, L. (2009). "Prospects for constraining quantum gravity dispersion with near term observations". Physical Review D 80: 084017. arXiv:0906.3731. Bibcode:2009PhRvD..80h4017A. doi:10.1103/PhysRevD.80.084017.

- ↑ Fermi LAT Collaboration (2009). "A limit on the variation of the speed of light arising from quantum gravity effects". Nature 462 (7271): 331–334. arXiv:0908.1832. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..331A. doi:10.1038/nature08574. PMID 19865083.

- ↑ Hossenfelder, S. (2009). "The Box-Problem in Deformed Special Relativity". arXiv:0912.0090. Bibcode:2009arXiv0912.0090H. Unsupported parameter(s) in cite arXiv (help)

See also

Further reading

- Amelino-Camelia, G. (2002). "Doubly-Special Relativity: First Results and Key Open Problems". International Journal of Modern Physics D 11 (10): 1643–1669. arXiv:gr-qc/0210063. Bibcode:2002IJMPD..11.1643A. doi:10.1142/S021827180200302X.

- Amelino-Camelia, G. (2002). "Relativity: Special treatment". Nature 418 (6893): 34–35. arXiv:gr-qc/0207049. Bibcode:2002Natur.418...34A. doi:10.1038/418034a. PMID 12097897.

- Cardone, F.; Mignani, R. (2004). Energy and Geometry: An Introduction to Deformed Special Relativity. World Scientific. ISBN 981-238-728-5.

- Jafari, N.; Shariati, A. (2006). "Doubly Special Relativity: A New Relativity or Not?". AIP Conference Proceedings 841. pp. 462–465. arXiv:gr-qc/0602075. doi:10.1063/1.2218214.

- Kowalski-Glikman, J. (2005). "Introduction to Doubly Special Relativity". Planck Scale Effects in Astrophysics and Cosmology. Lecture Notes in Physics 669. Springer. pp. 131–159. arXiv:hep-th/0405273. doi:10.1007/b105189. ISBN 978-3-540-25263-4.

- Smolin, Lee. (2006). "Chapter 14. Building on Einstein". The trouble with physics : the rise of string theory, the fall of a science, and what comes next. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-618-55105-7. OCLC 64453453. Smolin writes for the layman a brief history of the development of DSR and how it ties in with string theory and cosmology.

![[M_i,M_j]=i\epsilon_{ijk} M_k](../I/m/6fee7ffabfe36258315fe7db8cc5fff2.png)

![[N_i,N_j]=-i\epsilon_{ijk} M_k,](../I/m/72ba9d18e55f4faeede2f388a75e6473.png)

![[M_i,N_j]=-i\epsilon_{ijk} N_k](../I/m/a79b5a7dd2e03bdeca8ba40caf14927a.png)

![[M_i,p_j]=i\epsilon_{ijk} p_k](../I/m/506ebebcfbbbebf1d13a2871e84e159e.png)

![[M_i,p_0]=0](../I/m/56226fc88163c67007309ca4f3defa86.png)

![[N_i,p_j]=A\epsilon_{ij}+Bp_ip_j+C\Delta^\epsilon_{ijk}N_k](../I/m/0647b17a620a9fd72d8f7c34cc634180.png)

![[N_i,p_0]=Dp_i](../I/m/d1e3065584819270d4623ff3e75faa40.png)