Double-heading

In railroad terminology, double-heading or double heading indicates the use of two locomotives at the front of a train, each operated individually by its own crew. The practice of triple-heading involves the use of three locomotives.

Double-heading is most common with steam locomotives, but is also practised with diesel locomotives. It is not strictly the same practice as two or more diesel or electric locomotives working 'in multiple' (or 'multiple-working'), where both (or all) locomotives are controlled by a single driver in the cab of the leading locomotive.

Advantages

Double-heading is practised for a number of reasons:

- The most common reason is the need for additional motive power when a single locomotive is unable to haul the train due to uphill grades, excessive train weight, or a combination of the two.

- Double-heading is also used on passenger trains when one locomotive could suffice but would not be fast enough to maintain the schedule.

- More rarely, certain companies have used double-heading to guarantee a service when they have been aware of the poor quality of their locomotives, on the understanding that if one engine failed in service, the other would suffice to get the train to its destination.

- Double-heading is a useful practice on single lines even in the absence of a need for more power, as to double-head a train saves making a separate path for a spare engine; it can be repositioned using the traffic path occupied by the service train.

- As double-heading has become increasingly uncommon railway companies may advertise specially double-headed services as an attraction to enthusiasts; this occurs regularly but infrequently on the British mainline, whilst the Romney, Hythe & Dymchurch Railway in England advertises an annual day when all of its passenger trains are double-headed all day, both steam and diesel.

- In the United Kingdom, double-heading is used to provide redundancy for all trains hauling nuclear flasks (usually to/from Sellafield, Cumbria). For security and safety reasons, trains carrying nuclear waste cannot be allowed to be left standing after a breakdown.

Disadvantages

Double-heading requires careful cooperation between the engine crews, and is a skilled technique, otherwise one locomotive's wheels could slip, which could stall the train or even cause a derailment.

The risks of double heading as well as its costs (fuel and maintenance costs for the engines, wages for their crews) have led railroads to seek alternative solutions. Electrification has been used in many cases. The Milwaukee Road was able to switch from triple-headed steam locomotives to a single electric locomotive. The costs of running extra steam locomotives were eliminated, and average train speeds increased because it was no longer necessary to attach and detach the locomotives. In Britain, the Midland Railway used to use double-heading often, because it built only small, light locomotives, which were often not powerful enough to haul the trains alone. Several accidents on the Midland system were indirectly caused by this 'small engine policy' and the resulting reliance on double-heading. Some were caused by trains stalling despite being double-headed (such as the 1913 Ais Gill rail accident), whilst others were caused by excessive light-engine movements as locomotives that had been used for double-heading returned to their depots (the Hawes Junction rail crash in 1910). When the Midland was absorbed into the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, this practice was stopped because it was uneconomical, and more powerful locomotives were built.

Special terminology employed

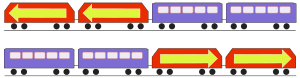

When a train formation includes two locomotives double-heading the service, they are commonly distinguished by the terms Pilot engine for the leading locomotive, and Train engine for the second locomotive. This should not be confused with the totally different procedure of adding a Banking engine to the rear of a train to assist up a hill or away from a heavy start.

For many years the Great Western Railway of the United Kingdom maintained a unique practice when double-heading was required. If an extra locomotive was to be added to the front of a train for a particular section of line the second 'pilot' engine would be coupled directly to the train while the original 'train' engine would remain at the front of the formation (the reverse of normal practice). The GWR's reasoning was that the driver of the original engine was in overall charge of the train, with the second locomotive merely assisting for a portion of the journey, thus his engine should be placed at the front. Despite requiring time-consuming shunting operations each time an engine had to be added or removed to a train this arrangement remained in place on parts of the GWR until nationalisation in 1948.