Dongui Bogam

| “Exemplar of Korean medicine” | |

| Hangul | 동의보감 |

|---|---|

| Hanja | 東醫寶鑑 |

| Revised Romanization | Dong(-)ui bogam |

| McCune–Reischauer | Tongŭi pogam |

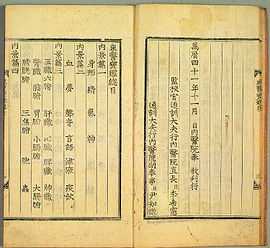

The Dongui Bogam (동의보감) is a Korean book compiled by the royal physician, Heo Jun (1539 – 1615) and was first published in 1613 during the Joseon Dynasty of Korea. The title literally means “Mirror of Eastern Medicine”. The book is regarded important in traditional Korean medicine and one of the classics of Oriental medicine today. As of July 2009, it is on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme.[1] The original edition of Dongui Bogam is currently preserved by the Korean National Library.[2] It is expected to be translated in English by 2013.[3] The original was written in Hanja and only part of it was transcribed in Korean for wide reading use, as only officials understood in Hanmun.[4]

Background

Known as one of the classics in the history of Eastern medicine, it was published and used in many countries including China and Japan, and remains a key reference work for the study of Eastern medicine. Its categorization and ordering of symptoms and remedies under the different human organs affected, rather than the disease itself, was a revolutionary development at that time. It contains insights that in some cases did not enter the medical knowledge of Europe until the twentieth century.[5]

Work on the Dongui Bogam started in the 29th year of King Seonjo’s reign (1596) by the main physicians of Naeuiwon (내의원, “royal clinic”), with the objective to create a thorough compilation of traditional medicine. Main physician Heo Jun led the project but work was interrupted due to the second Japanese invasion of Korea in 1597. King Seonjo did not see the project come to fruition, but Heo Jun steadfastedly stuck to the project and finally completed the work in 1610, the 2nd year of King Gwanghaegun’s reign.[2][6]

The book

The Dongui Bogam consists of 25 volumes. In comparison to Hyangyak jipseongbang (향약집성방, "Compilation of Native Korean Prescriptions") written in 1433, Dongui Bogam is more systematic. It was written referring not only to Korean medicine texts but also those of China, and practically recorded illnesses with their respective remedies.[7]

Contents

The book is divided into 5 chapters: Naegyeongpyeon (내경편, Internal Medicine), Oehyeongpyeon (외형편, External Medicine), Japbyeongpyeon (잡병편, Miscellaneous Diseases), Tangaekpyeon (탕액편, Remedies), and Chimgupyeon (침구편, Acupuncture).[7][8]

- Naegyeongpyeon primarily deals with physiologic functions and equivalent disorders of internal organs. The interactions of five organs - liver, lungs, kidneys, heart, and spleen - are thoroughly explained.

- Oehyeongpyeon explains the function of visible parts of the human body - skin, muscles, blood vessels, tendons, and bones - and the various related illnesses.

- Japbyeongpyeon deals with diagnosis and healing methods of various illnesses and disorders such as anxiety, over-excitement, stroke, cold, nausea, edema, jaundice, carbunculosis, and others. This chapter also has a section for pediatrics and gynecology.

- Tangaekpyeon details methods for creating remedies and potions such as the collection of medicinal herbs and plants, creating and handling of medication, correct prescription and administration of medicine. All herbal medicine is categorized with explanations regarding their strength, gathering period and their common names for easy understanding.

- Chimgupyeon explains the acupuncture procedures for various ailments and disorders.

Dongui Bogam offered not only medical facts, but also philosophical values of Eastern Asia. Heo Jun conveyed the message that maintaining the body’s energies in balance leads to one’s good health. The first page of the book is an anatomical map of the human body, linking human body with heaven and earth which embodies the Asian perspective of nature.[9]

Editions

There have been several print editions of Dongui Bogam besides the original Naeuiwon edition, within Korea and abroad. The first Chinese edition was printed in 1763 with additional prints in 1796, and 1890. The Japanese edition was first printed in 1724, and then 1799.[7]

UNESCO Memory of the World Register and controversy

In 2009, UNESCO decided to add Dongui Bogam to the cultural heritage list due to its contribution as a historical relic and it was placed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Programme, becoming Korea's seventh cultural heritage to be thus included.[10] However, doctors clashed over Dongui Bogam after the official listing. The Korean Medical Association (KMA) downplayed the book’s importance saying that “it shouldn’t be taken as anything more than a recognition of the book’s value as a historical relic. It should not be taken as an acknowledgement of traditional medicine for its superior effectiveness” Listing the fact that the book is full of quackery such as how to bore a son or how to make yourself invisible. The KMA emphasized that Dongui Bogam was merely a cultural artifact and not science. The Association of Korean Oriental Medicine (AKOM) criticized the doctors of KMA for the lack of their appreciation of the influence of Dongui Bogam and history, saying it is necessary “to inherit and advance traditional medicine”.[11]

See also

References

- ↑ The History of Science in Korea Korean Culture and Information Service (KOIS)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 (Korean) Dongui Bogam at Doosan Encyclopedia

- ↑ http://www.linkedin.com/groups/Koreas-Ancient-Medical-Book-Dongui-3748562.S.46407523

- ↑ https://www.koreatimes.co.kr/www/news/art/2011/04/142_49756.html

- ↑ http://www.koreanhero.net/fiftywonders/FiftyWonders2_English.pdf

- ↑ An ancient medical text gains worldwide recognition, Korean Press

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 (Korean) Dongui Bogam at Encyclopedia of Korean Culture

- ↑ , UNESCO

- ↑ (Korean) Dongui Bogam at Britannica Korea

- ↑ Dongui Bogam, Korea Times, 2009-07-31.

- ↑ Doctors Clash Over ‘Mirror of Eastern Medicine’, Korea Times, 2009-08-04.

External links

- Donguibogam: Principles and Practice of Eastern Medicine at UNESCO website

- 400 years of Dongui Bogam, Dongui Bogam Organization