Dominant-party system

| Part of the Politics series |

| Party politics |

|---|

| Political spectrum |

| Party platform |

|

| Party system |

|

|

| Coalition |

|

| Lists |

|

| Politics portal |

A dominant-party system or one-party dominant system, is a system where there is "a category of parties/political organizations that have successively won election victories and whose future defeat cannot be envisaged or is unlikely for the foreseeable future."[1] A wide range of parties have been cited as being dominant at one time or another, including the Kuomintang in the Republic of China, the African National Congress (ANC) in South Africa, the Liberal Democratic Party in Japan and Bangladesh Awami League in Bangladesh.[1]

Historical overview

Opponents of the "dominant party" system or theory argue that it views the meaning of democracy as given, and that it assumes that only a particular conception of representative democracy (in which different parties alternate frequently in power) is valid.[1] One author argues that "the dominant party 'system' is deeply flawed as a mode of analysis and lacks explanatory capacity. But it is also a very conservative approach to politics. Its fundamental political assumptions are restricted to one form of democracy, electoral politics and hostile to popular politics. This is manifest in the obsession with the quality of electoral opposition and its sidelining or ignoring of popular political activity organised in other ways. The assumption in this approach is that other forms of organisation and opposition are of limited importance or a separate matter from the consolidation of their version of democracy."[1]

One of the dangers of dominant parties is "the tendency of dominant parties to conflate party and state and to appoint party officials to senior positions irrespective of their having the required qualities."[1] However, in some countries this is common practice even when there is no dominant party.[1] In contrast to single-party systems, dominant-party systems can occur within a context of a democratic system. In a single-party system other parties are banned, but in dominant-party systems other political parties are tolerated, and (in democratic dominant-party systems) operate without overt legal impediment, but do not have a realistic chance of winning; the dominant party genuinely wins the votes of the vast majority of voters every time (or, in authoritarian systems, claims to). Under authoritarian dominant-party systems, which may be referred to as "electoralism" or "soft authoritarianism", opposition parties are legally allowed to operate, but are too weak or ineffective to seriously challenge power, perhaps through various forms of corruption, constitutional quirks that intentionally undermine the ability for an effective opposition to thrive, institutional and/or organizational conventions that support the status quo, or inherent cultural values averse to change.

In some states opposition parties are subject to varying degrees of official harassment and most often deal with restrictions on free speech (such as press club), lawsuits against the opposition, rules or electoral systems (such as gerrymandering of electoral districts) designed to put them at a disadvantage. In some cases outright electoral fraud keeps the opposition from power. On the other hand, some dominant-party systems occur, at least temporarily, in countries that are widely seen, both by their citizens and outside observers, to be textbook examples of democracy. The reasons why a dominant-party system may form in such a country are often debated: Supporters of the dominant party tend to argue that their party is simply doing a good job in government and the opposition continuously proposes unrealistic or unpopular changes, while supporters of the opposition tend to argue that the electoral system disfavors them (for example because it is based on the principle of first past the post), or that the dominant party receives a disproportionate amount of funding from various sources and is therefore able to mount more persuasive campaigns. In states with ethnic issues, one party may be seen as being the party for an ethnicity or race with the party for the majority ethnic, racial or religious group dominating, e.g., the African National Congress in South Africa (governing since 1994) has strong support amongst Black South Africans, the Ulster Unionist Party governed Northern Ireland from its creation in 1921 until 1972 with the support of the Protestant majority.

Sub-national entities are often dominated by one party due the area's demographic being on one end of the spectrum. For example the current elected government of the District of Columbia has been governed by Democrats since its creation in the 1970s, Bavaria by the Christian Social Union since 1957, Alberta by Progressive Conservatives since 1971. On the other hand, where the dominant party rules nationally on a genuinely democratic basis, the opposition may be strong in one or more subnational areas, possibly even constituting a dominant party locally; an example is South Africa, where although the African National Congress is dominant at the national level, the opposition Democratic Alliance is strong to dominant in the Province of Western Cape.

Examples

Current dominant-party systems

Africa

- National Liberation Front (FLN)

- In power since independence in 1962, sole legal party 1962-1989

- Led by President Abdelaziz Bouteflika

- Presidential election, 2009: Abdelaziz Bouteflika (FLN) elected with 90.24% of the vote

- Presidential election, 2014: Abdelaziz Bouteflika (FLN) elected with 81.53% of the vote

- Parliamentary election, 2007: FLN 136 of 389 seats

- Parliamentary election, 2012: FLN 208 of 462 seats

- Popular Movement for the Liberation of Angola, Movimento Popular de Libertação de Angola (MPLA)

- In power since independence, 11 November 1975; sole legal party, 1975–91

- Led by President José Eduardo dos Santos, in office since 10 September 1979

- In the presidential election of 1992, dos Santos (MPLA-PT) won 49.6% of the vote. As this was not an absolute majority, a runoff against Jonas Savimbi (40.1%) was required, but did not take place. Dos Santos remained in office without democratic legitimacy.

- Parliamentary election, 1992: MPLA 53.7% and 129 of 220 seats

- Parliamentary election, 2008: MPLA 81.6% and 191 of 220 seats

- New constitution, 2010: popular election of president abolished in favour of a rule that the top candidate of the most voted party in parliamentary elections becomes president.

- New parliamentary elections held on August 31, 2012: MPLA 71% and 175 of 220 seats, José Eduardo dos Santos (as head candidate) automatically confirmed as state president (holding now this office for the first time in accordance with the constitution).

- Botswana Democratic Party (BDP)

- Led by President Ian Khama, in office since 1 April 2008

- In power since 3 March 1965

- Parliamentary election, 2009: BDP 53.26% and 45 of 57 seats

- Cameroon People's Democratic Movement (Rassemblement Démocratique et Populaire du Cameroun, RDPC)

- Led by President Paul Biya, in office since 6 November 1982

- In power, under various names, since independence, 1 January 1960 (Sole legal party, 1966–1990)

- Presidential election, 2004: Paul Biya (RDPC) 70.9%

- Parliamentary election, 2007: RDPC 153 of 180 ttyl

- Patriotic Salvation Movement (Mouvement Patriotique de Salut de SMPS)

- Led by President Idriss Déby Itno, in office since 2 December 1990

- In power since 2 December 1990

- Presidential election, 2006: Idriss Déby (MPS) 64.7%

- Parliamentary election, 2002: MPS 110 of 155 seats

- Congolese Party of Labour (Parti Congolais du Travail, PCT)

- Led by President Denis Sassou-Nguesso, in office from 8 February 1979 to 31 August 1992 and since 15 October 1997

- In power, under various names, from 1963 to 1992 and since 1997 (Sole legal party, 1963–1990)

- Presidential election, 2002: Denis Sassou-Nguesso (PCT) 89.4%

- Parliamentary election, 2002: PCT 53 of 137 seats

- People's Rally for Progress (Rassemblement Populaire pour de Progrès, RPP)

- Led by President Ismail Omar Guelleh, in office since 8 May 1999

- In power since its formation in 1979 (Sole legal party, 1979–1992)

- Presidential election, 2005: Ismail Omar Guelleh (RPP) re-elected unopposed

- Parliamentary election, 2003: RPP in coalition, 62.4% and 65 of 65 seats

- Democratic Party of Equatorial Guinea (Partido Democrático de Guinea Ecuatorial, PDGE)

- Led by President Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo, in office since 3 August 1979

- In power since its formation in 1987 (Sole legal party, 1987–1991)

- Presidential election, 2002: Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo (PDGE) 97.1%

- Parliamentary election, 2004: PDGE 47.5% and 68 of 100 seats (91.9% and 98 of 100 seats including allies)

- Ethiopian People's Revolutionary Democratic Front (EPRDF)

- Led by Hailemariam Desalegn, in office since August 2012

- In power since 28 May 1991

- Parliamentary election, 2005: EPRDF 327 of 547 seats

- Gabonese Democratic Party (Parti Démocratique Gabonais, PDG)

- Led by President Ali Bongo Ondimba, in office since 16 October 2009

- In power, under various names, since 28 November 1958 (Sole legal party, 1968–1991)

- Presidential election, 2009: Ali Bongo Ondimba (PDG) 41.7%

- Parliamentary election, 2006: PDG 82 of 120 seats (99 of 120 seats including allies)

- Alliance for Patriotic Reorientation and Construction (APRC)

- Led by President Yahya Jammeh, in office since 22 July 1994

- In power since its formation in 1996

- Presidential election, 2006: Yahya A. J. J. Jammeh (APRC) 67.3%

- Parliamentary election, 2007: APRC 42 of 48 seats

- Mozambican Liberation Front (FRELIMO)

- Led by President Armando Guebuza, in office since 2 February 2005

- In power since independence, 25 June 1975 (Sole legal party, 1975–1990)

- Presidential election, 2004: Armando Guebuza (FRELIMO) 63.7%

- Parliamentary election, 2004: FRELIMO 62.0% and 160 of 250 seats

- South West Africa People's Organisation (SWAPO)

- Led by President Hifikepunye Pohamba, in office since 21 March 2005

- In power since independence, 21 March 1990

- Presidential election, 2004: Hifikepunye Pohamba (SWAPO) 76.4%

- Parliamentary election, 2004: SWAPO 55 of 72 seats

- People's Democratic Party (PDP)

- Led by President Goodluck Jonathan, in office since 5 May 2010

- In power since 29 May 1999

- Presidential election, 2011: Goodluck Jonathan (PDP) 58.9%

- Parliamentary election, 2003: PDP 54.8% and 198 of 318 seats

- Rwandan Patriotic Front (RPF)

- Led by President Paul Kagame, in office since 24 March 2000

- In power since 19 July 1994

- Presidential election, 2003: Paul Kagame (RPF) 95.1%

- Parliamentary election, 2003: RPF 73.8% and 40 of 53 seats

- People's Party

- Led by President James Michel, in office since 14 April 2004

- In power since 5 June 1977 (Sole legal party, 1979–1991)

- Presidential election, 2006: James Michel (SPPF) 53.7%

- Parliamentary election, 2007: SPPF 56.2% and 23 of 34 seats

- African National Congress (ANC)

- Led by President Jacob Zuma, in office since 9 May 2009

- In power since 10 May 1994

- Parliamentary election, 2014: ANC 62.15% and 249 of 400 seats

- Sudan People's Liberation Movement (SPLM)

- Led by President Salva Kiir Mayardit, in office since 9 July 2011; and was President of Southern Sudan since 30 July 2005

- In power since independence, 9 July 2011; and in the autonomous Government of Southern Sudan since formation, July 9, 2005

- Presidential election, 2010: Salva Kiir Mayardit (SPLM) 92.99%

- Parliamentary election, 2010: SPLM 160 of 170 seats

- National Congress (NC)

- Led by President Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir, in office since 30 June 1989

- In power since its formation, 16 October 1993

- Presidential election, 2010: Omar Hassan Ahmad al-Bashir (NC) 68.24%

- Parliamentary election, 2010: NC 306 of 450 seats

- Chama cha Mapinduzi (CCM)

- Led by President Jakaya Kikwete, in office since 21 December 2005

- In power, under various names, since independence, 9 December 1961 (Sole legal party, 1964–1992)

- Presidential election, 2005: Jakaya Kikwete (CCM) 80.3%

- Parliamentary election, 2005: CCM 206 of 232 seats

- Rally of the Togolese People (RPT)

- Led by President Faure Gnassingbé, in office since 5 February 2005

- In power since its formation in 1969 (Sole legal party, 1969–1991)

- Presidential election, 2005: Faure Gnassingbé (RPT) 60.2%

- Parliamentary election, 2007: RPT 50 of 81 seats

- National Resistance Movement (NRM)

- Led by President Yoweri Museveni, in office since 29 January 1986.

- In power as de facto dominant party since 29 January 1986 as a "non-party Movement."

- Became de jure dominant party with the return of multi-party elections on 28 July 2005.

- Presidential election, 2006: Yoweri Museveni (NRM) 59.26%

- Parliamentary election, 2006: NRM 205 of 319 seats

- Presidential election, 2011: Yoweri Museveni (NRM) 68.38%

- Parliamentary election, 2011: NRM 263 of 375 seats

- Zimbabwe African National Union – Patriotic Front (ZANU-PF)

- Led by President Robert Mugabe, in office since 18 April 1980 (as president since 31 December 1987)

- In power since independence, 17 April 1980

- Presidential election, 2002: Robert Mugabe (ZANU-PF) 56.2%

- House of Assembly election, 2005: ZANU-PF 59.6% and 78 of 120 elective seats (30 additional seats reserved for appointees)

- Senate election, 2005: ZANU-PF 73.7% and 43 of 50 elective seats (16 additional seats reserved for appointees and traditional chiefs)

Americas

- The Barbuda People's Movement has ruled the island of Barbuda since 1979, and has won every election for the island's seat in the national House of Representatives.

- The Brazilian Social Democratic Party has ruled the state of São Paulo since 1995; the current term is due to end on January 1, 2015. On the other hand, its main rival, the Workers' Party has ruled the state of Acre since 1999, with a term also due to end on January 1, 2015. The Brazilian Democratic Movement Party has ruled the state of Goiás from March 15, 1983 until January 1, 1999. On the municipal level, the Workers' Party has ruled the city of Porto Alegre for sixteen years from January 1, 1989 to January 1, 2005.

- The Canadian province of Alberta has been ruled continuously by the Progressive Conservative Party since 1971. Prior to that, the Social Credit Party held power for 36 years from 1935 to 1971.

- The National Liberation Party in Costa Rica is the party with the major number of elected presidentes, consecutive periods and is the largest and oldest current party.

- The Seneca Party is the dominant party in the elections of the Seneca Nation of New York and has won every presidential election in recent memory. Only since the mid-2000s have there been any serious challenges to the party's dominance, all of which have failed.

- United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV), previously Fifth Republic Movement, formed by a coalition of nearly all pro-Chávez parties.

- Led by President of Venezuela Nicolas Maduro, in office since 2013

- Presidential election, 2013: Nicolas Maduro 50,78%

- Parliamentary election, 2010: 96 of 167 seats

The ![]() United States as a whole has a two-party system, with the main parties since the mid-1800s being Democratic Party and the Republican Party. However, some states and cities have been dominated by one of these parties for up to several decades.

United States as a whole has a two-party system, with the main parties since the mid-1800s being Democratic Party and the Republican Party. However, some states and cities have been dominated by one of these parties for up to several decades.

Dominated by the Democratic Party

-

Arkansas has been dominated by Democrats but they are more conservative than the national party is in general, the last Democratic presidential nominee to win Arkansas's electoral votes was Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996 respectively.

Arkansas has been dominated by Democrats but they are more conservative than the national party is in general, the last Democratic presidential nominee to win Arkansas's electoral votes was Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996 respectively. -

California

California -

District of Columbia has been continuously ruled by Democrats since the Home Rule Act of 1973 was passed.

District of Columbia has been continuously ruled by Democrats since the Home Rule Act of 1973 was passed. -

Chicago has been historically dominated by the Cook County Democratic Party - the office of mayor has been filled by a Democrat continuously since 1931.

Chicago has been historically dominated by the Cook County Democratic Party - the office of mayor has been filled by a Democrat continuously since 1931. - Milwaukee has been dominated by Democrats since the 1960s. Beforehand, it was dominated by the "Sewer Socialism" movement.

-

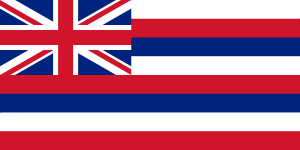

Hawaii has been dominated by Democrats since the Democratic Revolution of 1954. Beforehand, the state was dominated by Republicans and a sugar oligarchy.

Hawaii has been dominated by Democrats since the Democratic Revolution of 1954. Beforehand, the state was dominated by Republicans and a sugar oligarchy. -

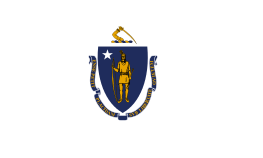

Massachusetts has been dominated by Democrats for several decades, save a few Republican governors.

Massachusetts has been dominated by Democrats for several decades, save a few Republican governors. -

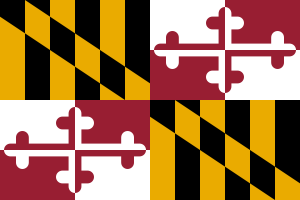

Maryland has been dominated by Democrats since the Civil War, with some exceptions.

Maryland has been dominated by Democrats since the Civil War, with some exceptions. -

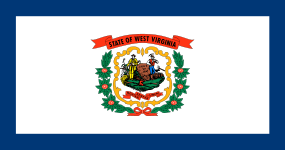

West Virginia has been dominated by Democrats in recent decades, but they are more conservative than the national party is in general; West Virginia is considered to be solidly Republican for the purposes of presidential elections. State politics are fueled in part by significant coal reserves that have led to an increased presence of organized labor, compared to the national average.

West Virginia has been dominated by Democrats in recent decades, but they are more conservative than the national party is in general; West Virginia is considered to be solidly Republican for the purposes of presidential elections. State politics are fueled in part by significant coal reserves that have led to an increased presence of organized labor, compared to the national average.

Dominated by the Republican Party

-

Arizona: a "Republican party stronghold" in recent decades.

Arizona: a "Republican party stronghold" in recent decades. -

Idaho has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence.

Idaho has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. -

Kansas has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. Since 1967, however, five of the last nine governors have been Democrats.[4]

Kansas has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. Since 1967, however, five of the last nine governors have been Democrats.[4] -

Nebraska has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence.

Nebraska has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. -

South Carolina: Solid South; dominated by Republicans since the mid-1990s.

South Carolina: Solid South; dominated by Republicans since the mid-1990s. -

South Dakota has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence.

South Dakota has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. -

Texas: Solid South; dominated by Republicans since the mid-1990s.

Texas: Solid South; dominated by Republicans since the mid-1990s. -

Utah has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence.

Utah has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence. -

Wyoming has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence, save a few Democratic governors.

Wyoming has been dominated by Republicans for most of its existence, save a few Democratic governors.

Asia / Oceania

- Cambodian People's Party (Kanakpak Pracheachon Kampuchea) (CPP)

- Led by Prime Minister Hun Sen, in office since 14 January 1985

- In power since 1981

- Barisan Nasional (National Front), a coalition of 14 parties led by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO)

- Led by Prime Minister Najib Tun Razak, in office since 3 April 2009[5]

- In power since independence, 28 August 1957

- Parliamentary election, 2013: UMNO 29.45% and 88 out of 222 seats, total for Barisan Nasional 47.38% and 133 out of 222 seats[6]

- Human Rights Protection Party (HRPP)

- Led by Prime Minister Tuila'epa Sailele Malielegaoi, in office since 23 November 1998

- In power since 1982

- Parliamentary election, 2006: HRPP 35 of 49 seats

- People's Action Party (PAP)

- Led by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, in office since 12 August 2004

- In power since 3 June 1959

- Parliamentary election, 2011: PAP won 60.1% of the popular vote and 81 (of which 5 were uncontested) out of 87 seats

- National Progressive Front (NPF), a coalition of 10 parties led by the Arab Socialist Ba'ath Party – Syria Region (Baath Party)

- Led by President Bashar al-Assad, in office since 17 July 2000

- In power since 8 March 1963

- Parliamentary election, 2012: Baath Party won 135 out of 250 seats, total for NPF 168 of 250 seats

- People's Democratic Party of Tajikistan is headed by President Emomalii Rahmon

- In power since 1994

- Presidential election in 2013 won by Emomali Rahmon 83,92%.

- Since Parliamentary election in 2010 holds 55 seats in Assembly of Representatives.

- Democratic Party of Turkmenistan is headed by Kasymguly Babaev since 18 August 2013.

- Currently holds 47 of 125 seats in the Assembly of Turkmenistan.

- Presidential election in 2012 won by Gurbanguly Berdimuhammedow 97,14%.

- Until 2012 it was the sole legal party in Turkmenistan.

- General People's Congress (GPC)

- Since 2012 led by President Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi

- In power since the unification of North Yemen and South Yemen in 1990

- Presidential Election, 2012: Abd Rabbuh Mansur Hadi (GPC) 99,8%

- Parliamentary Election, 2003: GPC 58.0% and 238 out of 301 seats

Eurasia

- The Republican Party of Armenia is the dominant party in Armenia since the election of Robert Kocharyan as President, continuing under his successor Serzh Sargsyan.

- New Azerbaijan Party (YAP) has been in power essentially continuously since 1993.

- Nur Otan is headed by President Nursultan Nazarbayev since 4 July 2007.

- Since last parliamentary election in 2012 holds 83 of 107 seats in the Majilis.

- Presidential election in 2011 won by Nursultan Nazarbayev 95,55%.

- Justice and Development Party

- Led by Recep Tayyip Erdoğan

- In power since 2002

- General election, 2011: 49.83% and 327 of 550 seats

- Local elections, 2014: 42.87%

- United Russia

- Led by President Vladimir Putin (President 2000-2008, and since 2012; Prime Minister 1999–2000, 2008–2012), nominated President Dmitry Medvedev (2008–2012)

- In power since 2003

- Presidential election, 2012: Vladimir Putin 63.60%

- Parliamentary election, 2011: 49.32% and 238 of 450 seats

Europe

- Christian Social Union has dominated politics in the state of Bavaria since 1957.

- With the exception of two coalition governments, they have formed the government on their own ever since.

- In 1994, MSZP won 45% of the popular vote, which translated into 54% of the seats. With its long term ally and coalition partner SZDSZ they acquired 72% of the seats in the parliament, more than the 67% required for the modification of the constitution.

- In 2010, the alliance of Fidesz and KDNP won 53% of the popular vote, which translated into 68% of the seats. This enabled the governing party alliance to enact a new constitution for Hungary.

- The Democratic Party, led by the Prime Minister Matteo Renzi, gained 41% of votes in the 2014 European election, becoming the most voted party in whole Europe; it was the best result for an Italian party in nationwide election since Christian Democracy's result in 1958 election.[10] The PD is often referred to as the "Nation Party".[11]

- Previously the Italian Communist Party, and now its natural heir the Democratic Party have dominated the so-called Red regions (Emilia-Romagna, Tuscany, Umbria and Marche) since the establishment of the Republic in 1946.

- The Christian Social People's Party (CSV), with its predecessor Party of the Right, has governed Luxembourg continuously since 1917, except for 1974–79. However, Luxembourg has a coalition system, and the CSV has been in coalition with at least one of the two next two leading parties for all but four years. It has always won a plurality of seats in parliamentary elections, although it has lost the popular vote in 1964 and 1974.

- Democratic Party of Socialists of Montenegro, founded in 1943 as Communist Party of Montenegro, part of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia

- Led by Milo Đukanović, five time Prime Minister (1991–1998, 2003–2006, 2008–2010) and former President (1998–2002)

- In power since establishment of Communist rule in Montenegro/Yugoslavia in 1944/5 (Sole legal party, 1945–1990)

- Presidential election, 2008: Filip Vujanović (DPS CG), 51.89%

- Parliamentary election, 2009: DPS CG in coalition, 51.94% and 48 (35) of 81 seats

- Social Democratic Party has dominated political life in the autonomous region of Madeira since the first regional elections, in 1976. Alberto João Jardim has been serving as President of the Regional Government uninterruptedly since 1978.

- Serbian Progressive Party

- Led by Aleksandar Vučić

- Parliamentary election, 2014: 48.35% and 158 of 250 seats

- Welsh Labour Party is dominant in Wales

- Led by First Minister Carwyn Jones (First Minister since 2009)

- In power since 1999

- UK general election, 2010 in Wales: Won 26 of 40 Welsh seats to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom

- National Assembly for Wales election, 2011: 42.3% and 30 of 60 seats

Former dominant parties

North America

Canada: The Liberal Party of Canada was the dominant party in the federal government of Canada for so much of its history that it is sometimes given the moniker "Canada's natural governing party".[14] The party experienced several long uninterrupted periods in power including 1873-1878, 1896-1911, 1921-1926, 1926-1930, 1935-1957, 1963-1979, 1980-1984, and 1993-2006.

Canada: The Liberal Party of Canada was the dominant party in the federal government of Canada for so much of its history that it is sometimes given the moniker "Canada's natural governing party".[14] The party experienced several long uninterrupted periods in power including 1873-1878, 1896-1911, 1921-1926, 1926-1930, 1935-1957, 1963-1979, 1980-1984, and 1993-2006.

British Columbia: The Social Credit Party held power for all but 3 years between 1952 and 1991, winning 11 of the 12 elections held during this 39-year period.

British Columbia: The Social Credit Party held power for all but 3 years between 1952 and 1991, winning 11 of the 12 elections held during this 39-year period.  Alberta: The Social Credit Party governed Alberta from 1935 to 1971, and the Alberta PC Party has held power since 1971.

Alberta: The Social Credit Party governed Alberta from 1935 to 1971, and the Alberta PC Party has held power since 1971.  Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Liberal Party, in the Province of Nova Scotia, held office in an unbroken period from 1882 to 1925. During the period from 1867 to 1956, the party was in power for 76 of 89 years, most of that time with fewer than 5 opposition members.

Nova Scotia: The Nova Scotia Liberal Party, in the Province of Nova Scotia, held office in an unbroken period from 1882 to 1925. During the period from 1867 to 1956, the party was in power for 76 of 89 years, most of that time with fewer than 5 opposition members. Ontario: The Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, in the Province of Ontario, held office from 1943 to 1985.

Ontario: The Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario, in the Province of Ontario, held office from 1943 to 1985.

Mexico: The Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) in Mexico ruled from 1929 to 2000 and again since 2012.

Mexico: The Revolutionary Institutional Party (PRI) in Mexico ruled from 1929 to 2000 and again since 2012.

- During the "Era of Good Feeling," the Democratic-Republican Party dominated national politics with no effective opposition from the Federalist Party or any third parties, allowing James Monroe to run unopposed in the 1820 presidential election. This dominance continued until the rise of the American Whig Party circa 1830.

- Southern United States:

- The South (usually defined as coextensive with the former Confederacy, with the exception of western and sometimes central Texas) was known until the era of the civil-rights movement as the "Solid South" due to its states' reliable support of the United States' Democratic Party. Several states had an unbroken succession of Democratic governors for several decades or over a century.

Alabama, 1874-1987 (113 years)

Alabama, 1874-1987 (113 years) Arkansas, 1874-1967 (93 years)

Arkansas, 1874-1967 (93 years) Florida, 1877-1967 (90 years)

Florida, 1877-1967 (90 years).svg.png) Georgia, 1872-2003 (131 years)

Georgia, 1872-2003 (131 years) Louisiana, 1877-1980 (103 years)

Louisiana, 1877-1980 (103 years) Mississippi, 1876-1992 (116 years)

Mississippi, 1876-1992 (116 years) South Carolina, 1876-1975 (99 years)

South Carolina, 1876-1975 (99 years) Texas, 1874-1979 (105 years)

Texas, 1874-1979 (105 years) Virginia, 1869-1970 (101 years)

Virginia, 1869-1970 (101 years)

- During and after that movement, however, factors such as the national Democratic Party's support for the civil-rights movement and the national Republican Party's "Southern strategy" and support for the application of religious values to politics eroded the South's support for the Democrats.

Caribbean and Central America

- The Popular Democratic Party in Puerto Rico from 1949 to 1969.

- The Antigua Labour Party in Antigua and Barbuda, 1960–1971 and 1976–2004.

- The United Bermuda Party in Bermuda from 1968 to 1998.

- The Progressive Liberal Party in the Bahamas from 1967 to 1992 and 2002–2007

South America

- The Liberal Party of Colombia from 1863 to 1880

- The National Autonomist Party (PAN) of Argentina from 1874 to 1916

- The Colorado Party of Uruguay, between 1868 and 1959

- The Colorado Party of Paraguay, 1880–1904 and 1947–2008. They were the sole legal party from 1947 to 1962.

- The Revolutionary Nationalist Movement (MNR) in Bolivia from 1952 to 1964.

- The National Renewal Alliance Party (ARENA) in Brazil from 1965 to 1979

Europe

- In Turkey's single-party period, the Republican People's Party became the major political organisation of a single-party state. However, CHP faced two opposition parties during this period, both established upon the request of the founder of Turkey and CHP leader, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, in efforts to jump-start multiparty democracy in Turkey.[15]

- Italy's Christian Democracy dominated the Italian politics for almost 50 years as the major party in every coalition that governed the country from 1944 until its demise amid a welter of corruption allegations in 1992–1994. The main opposition to the Christian democratic governments was the Italian Communist Party.

- The Portuguese Republican Party, during most of the Portuguese First Republic's existence (1910–1926): After the coup that put an end to Portugal's constitutional monarchy in 1910, the electoral system, which had always ensured victory to the party in government, was left unchanged. Before 1910, it had been the reigning monarch's responsibility to ensure that no one party remain too long in government, usually by disbanding Parliament and calling for new elections. The republic's constitution added no such proviso, and the Portuguese Republican Party was able to keep the other minor republican parties (monarchic parties had been declared illegal) from winning elections. On the rare occasions when it was ousted from power, it was overtrown by force and was again by the means of a counter-coup that it returned to power, until its final fall, with the republic itself, in 1926.

- The Party of the Right in Luxembourg (1917–1925)

- The Ulster Unionist Party in the former devolved administration of Northern Ireland between 1921 to 1972.[16]

- The Swedish Social Democratic Party in Sweden from 1932 to 1976 except only for some months in 1936 (1936–1939 and 1951–1957 in coalition with the Farmers' League, 1939–1945 at the head of a government of national unity) It has also held the power the vast majority of elections even after 1976, and is still the largest party in Sweden.

- The Norwegian Labour Party ruling from 1935 to 1965, though it has been the biggest party in Norway since 1927 and has been in power many other times.

- The Scottish Labour Party won every election in Scotland between the 1960s and the present day and controlled the Scottish Parliament until the 2007 election.

- Convergència i Unió coalition (federated political party after 2001) in Catalonia governed the autonomous Catalan government from 1980 to 2003 under the leadership of Jordi Pujol with parliamentary absolute majority or in coalition with other smaller parties.

- The Socialist Party of Serbia in FR Yugoslavia from 1992 to 2000.

- Ireland's Fianna Fáil was the largest party in Dáil Éireann between 1932 to 2011 and in power for 61 of those 79 years. However, the party were heavily defeated in the Irish general election, 2011, coming third.

Asia

- The Nacionalista Party in the Philippines was the dominant party during various times in the nation's history from 1916–1941, and on 1945

- he Indian National Congress was in power both at the Union and many states from 1946 to 1989 and also from 2005 to 2014.[17]

- In Bangladesh, the Awami League was the country's predominant political party between 1972 and 1975. After the military coup of 1975, the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) became the dominant political force between 1977 and 1982. Under the autocratic regime of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad, the Jatiya Party was the dominant party between 1986 and 1990. Currently, Bangladesh Awami League again has become the dominant political force since 2008.

- The Sangkum in Cambodia was the dominant party under Prince Norodom Sihanouk as head of government from 1955-1970.

- The Social Republican Party of the Khmer Republic (now Cambodia) was the dominant party under General Lon Nol from 1972-1975.

- The Anti-Fascist People's Freedom League in Burma (now Myanmar) from 1948 to 1962.

- The Kuomintang established a de facto one-party state in the Republic of China on the mainland and subsequently on Taiwan until political liberalization and the lifting of martial law in the late 1970s. The Kuomintang continued to dominate the political system until the victory of the opposition Democratic Progressive Party in the 2000 presidential election - it has maintained control of the Legislative Yuan since 1928.

- Japan Liberal Democratic Party, in power 1955–1993, 1994–2009 and since 2012.

- The Golkar (Acronym of Golongan Karya or Functional Group) in Indonesia from 1971 to 1999.

- Kilusang Bagong Lipunan in the Philippines from 1978 to 1986.

Africa

- The National Party in South Africa from 1948 to 1994.

- The National Democratic Party (NDP) of Egypt, under various names, from 1952 to 2011 (as Arab Socialist Union, sole legal party 1953–1978)

- The Democratic Constitutional Rally in Tunisia, 1956-2011 (as the sole legal party between 1963 and 1981)

- The Socialist Party in Senegal from 1960 to 2000.

- The Rhodesian Front in Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), under the leadership of Ian Smith, from 1962 to 1979.

- The People's Progressive Party in The Gambia from 1962 to 1994.

- The Party of Unity and Progress was in power in Guinea since its formation in 1992 until it was overthrown by a military coup in December 2008.

- The Movement for Multiparty Democracy in Zambia from 1991 to 2011.

See also

- List of democracy and elections-related topics

- Loyal opposition

Footnotes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 Suttner, R. (2006), "Party dominance 'theory': Of what value?", Politikon 33 (3), pp. 277-297

- ↑ Mehler, Andreas; Melber, Henning; Van Walraven, Klaas (2009). Africa Yearbook: Politics, Economy and Society South of the Sahara in 2008. Leiden: Brill. p. 411. ISBN 978-90-04-17811-3.

- ↑ http://www.bti-project.org/country-reports/esa/ago/ (English)

- ↑ "State of Kansas Governors". TheUS50.com. Retrieved August 26, 2014.

- ↑ "Biography: Office of the Prime Minister". Office of the Prime Minister of Malaysia. 30 April 2014. Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ "13th Malaysian General Election". The Star (Petaling Jaya). Retrieved 12 November 2014.

- ↑ http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/default.aspx?pageid=438&n=akp-ushering-in-8216dominant-party-system8217-says-expert-2011-06-17

- ↑ http://www.journalofdemocracy.org/article/turkey-under-akp-era-dominant-party-politics

- ↑ http://www.suits.su.se/about-us/events/open-lectures/turkey-s-party-system-in-change-the-emerging-dominant-party-system-and-the-main-opposition-party-1.155761

- ↑ È il Pd dei record. A pezzi M5S e Forza Italia. Lega Nord ok, Ncd e Tsipras col quorum.

- ↑ Renzi alla dimensione dem: "PD sia partito della Nazione".

- ↑ Glasali ste, gledajte (in Serbian), Vreme, 16 March 2014

- ↑ http://www.economist.com/news/britain/21567075-scotland-wales-growing-more-independent-westminster-unlike-scotland-it-isnt-too

- ↑ Canada's 'natural governing party'. CBC News in Depth, 4 December 2006. Retrieved 2012-08-10.

- ↑ http://www.utoronto.ca/ai/learningtolose/participants.html

- ↑ Garnett, Mark; Lynch, Philip (2007). Exploring British Politics. London: Pearson Education. p. 322. ISBN 978-0-582-89431-0.

- ↑ Johari, J. C. (1997). Indian Political System: a Critical Study of the Constitutional Structure and the Emerging Trends of Indian Politics. New Delhi: Anmol Publications. p. 250. ISBN 978-81-7488-162-5.