Djedkare Isesi

| Djedkare Isesi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tankeris | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

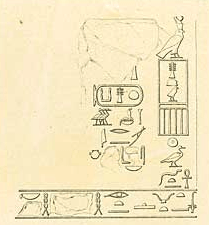

Gold cylinder seal bearing the names and titles of the pharaoh Djedkare Isesi. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 2414–2375 BC (5th dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Menkauhor Kaiu | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Unas | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | possibly Meresankh IV? | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

Isesi-ankh Neserkauhor Raemka? Kaemtjenent? Kekheretnebti Meret-Isesi Hedjetnebu Nebtyemneferes | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 2375 BC | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Djedkare Isesi in Greek known as Tancheres[1] from Manetho's Aegyptiaca, was a Pharaoh of Egypt during the Fifth dynasty. He is assigned a reign of twenty-eight years by the Turin Canon although some Egyptologists believe this is an error and should rather be thirty-eight years. Manetho ascribes to him a reign of forty-four years while the archaeological evidence suggests that his reign is likely to have exceeded thirty-two years. Djedkare's prenomen or royal name means "The Soul of Ra Endureth."[2]

Family

It is not known who Djedkare's parents were. Djedkare could be Menkauhor's son, or Niuserre's son. He may have been either a son, brother or cousin of his predecessor Menkauhor. Similarly the identity of his mother is unknown.[3]

The name of Djedkare Isesi's principal wife is not known. An important queen consort was very likely the owner of the pyramid complex located to the northeast of Djedkare's pyramid in Saqqara. The queen's pyramid had an associated temple and it had its own satellite pyramid. Baer suggested that the reworking of some of the reliefs may point to this queen ruling after the death of Djedkare. It is possible that this queen was the mother of Unas, but no conclusive evidence exists to support this theory.[3]

Queen Meresankh IV has been suggested as a possible wife of Djedkare,[3] but she is more commonly thought to be a wife of Menkauhor.[4]

Djedkare's sons were:[4]

- Prince Isesi-ankh, buried in Saqqara.

- Prince Neserkauhor, buried in Abusir.

It is possible that Prince Raemka[3] and Prince Kaemtjenent[4] are sons of Djedkare, but more commonly thought to be a son of Menkauhor.

His daughters include:[4]

- Kekheretnebti, King's Daughter of his Body, buried in Abusir. She had a daughter named Tisethor.

- Meret-Isesi, King's Daughter of his Body, buried in Abusir.

- Hedjetnebu, King's Daughter of his Body, buried in Abusir.

- Nebtyemneferes, King's Daughter, buried in Abusir.

- Kentkhaus, King's daughter of his Body, wife of Vizier Senedjemib Mehi, was likely a daughter of Djedkare Isesi.[5]

Biography

Djedkare Isesi did not, as was customary for his dynasty, build his own sun temple, but did build his pyramid at Saqqara instead of Abusir. This is believed to be a sign that Osiris had now replaced the sun-god Ra as the most popular god. Titles were now thought to hold magical power; their growing importance believed to be a sign of a gradual decentralization of power.

Evidence from the area near Memphis

Several people from the reign of Djedkare Isesi are known through their tombs in Giza. Cemetery 2000 contains several tombs of overseers and inspectors of the Palace attendants.[6] These people are thought to have held functions in the royal palace. The inspectors of the palace attendants include Redi (G 2086), Kapi (G 2091), and Pehenptah (G 2088). Some of these individuals attested in Giza held further position within the royal court.

A courtier named Saib (G 2092+2093) was also a companion and held the positions of director of the palace. Saib was also secretary of the House of Morning. Saib was buried in a double mastaba. He may have shared this tomb with his wife Tjentet, who was a priestess of Neith. Nimaatre (G 2097) was another palace attendant of the Great House. Nimaatre may have been related to Saib, but this is not certain. Nimaatre also served as secretary of the Great House (i.e. the Palace).

A man named Nefermesdjerkhufu (G 2240) was companion of the house, overseer of the department of palace attendants of the Great House, he who is in the heart of his lord, and secretary. He also held the positions of overseer of the two canals of the Great House, and he held a porition related to the royal documents.[7]

A nobleman by the name of Kaemankh (G 4561) was royal acquaintance and was associated with the royal treasury. Kaemwankh was an inspector of administrators of the treasury, and secretary of the king's treasure.[8][9]

Possibly one of the best known nobles from the time of Djedkare is his vizier Ptahhotep who was buried in Saqqara.

Djedkare had another vizier by the name of Rashepses. A letter directed to Rashepses has been preserved. This decree is inscribed in his tomb in Saqqara.

Another well attested vizier was Senedjemib Inti. Senedjemib Inti was buried in Giza; in mastaba G 2370. He is described as true count Inti, chief justice and vizier Senedjemib, and the royal chamberlain Inti. Letters from Djedkare to his Vizier have been preserved because Senedjemib Inti had them inscribed in his tomb. One royal decree is addressed to the chief justice overseer of all works of the king and overseer of scribes of royal documents, Senedjemib. This decree mentions the planning of a court in the pool area(?) of the jubilee palace called "Lotus-of-Isesi". This decree is dated to either the 6th or 16th count, 4th month of the 3rd season, day 28. A second letter concerns a draft of the inscriptions of a structure called the "Sacred Marriage Chapel of Isesi". The third decree recorded in Inti's tomb mentions the construction of a lake.[10]

Senedjemib Inti died during the reign of Djedkare Isesi. Inscriptions in the tomb of Inti describe how his son, Senedjemib Mehi, asks and receives permission to bring a sarcophagus from Tura. Senedjemib Mehi would later follow in his father's footsteps and become vizier during the reign of one of Djedkare's successors.[11]

Evidence of activity outside Egypt

Inscriptions in the Sinai - in Wadi Maghareh - shows a continued presence during the reign of Djedkare Isesi. Expeditions were sent to find and bring back semi-precious stones such as turqoise. Inscriptions can be dated to the 3rd (or 4th) and 9th cattle count.[13]

Djedkare is known to sent expeditions to Byblos and Punt.[14] The expedition to Punt is referred to in the letter from Pepi II to Harkuf some 100 years later. Harkuf had reported that he would bring back a "dwarf of the god's dancers from the land of the horizon dwellers". Pepi mentions that the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum had returned from Punt with a dwarf during the reign of Djedkare Isesi and had been richly rewarded. The decree mentions that "My Majesty will do for you something greater than what was done for the god's sealbearer Werdjededkhnum in the reign of Isesi, reflecting my majesty's yearning to see this dwarf".[15]

Recent excavations in Ain Sukhna, a port on the western shore of the Red Sea's Gulf of Suez, have revealed the activities of Djedkare Isesi in this area. The site is situated 55 km south of Suez.

Large galleries carved into the sandstone mountain were found. They served as living and storage places. In one of them, a wall inscription from the time of Djedkare Isesi has been found. The inscription gives details on a large expedition in the area, looking for various minerals.

Ain Sukhna served as a staging area for expeditions to Wadi Maghareh and other parts of the Sinai.[16]

Length of Reign

An entire series of dated administrative papyri from Djedkare's reign was discovered in king Neferirkare's mortuary temple. According to Miroslav Verner, Djedkare Isesi's highest known date is a Year of the 22nd Count, IV Akhet day 12 papyrus.[17] Verner writes that Paule Posener-Kriéger transcribed the year date numeral in the papyrus here as the 'year of the 21st count' in P. Posener-Kriéger, J.L de Cenival, The Abusir Papyri, London 1968, Plates 41 & 41A; however; Verner notes that in "the damaged place where the numeral still is, one can see a tiny black trace of another vertical stroke just visible. Therefore, the numeral can probably be reconstructed as 22."[17] This date would belong anywhere from Year 32 to Year 44 of Djedkare's reign depending on whether the cattle count was biennial (once every 2 years) or once evey year and a half. Djedkare Isesi's reign is well documented by the Abusir Papyri, numerous royal seals and contemporary inscriptions; taken together, they indicate a fairly long reign for this king.[18] Another element in favor of a long reign is an alabster vase E5323 on display at the Louvre museum celebrating Djedkare's first Sed festival, an event occurring on the 30th year on the throne of a king. An examination of the king's skeletal remains, found in the king's pyramid in the mid-1940s by Abdel Salam Hussein and A. Varille, by A. Batrawi suggest that Djedkare died at the age of 50 to 60 years old.[19]

Burial

Djedkare moved from Abusir to South Saqqara to construct his pyramid complex. His pyramid was called "Beautiful is Djedkare". Today it is called Haram el-Shawaf El-Kably which means "the Southern Sentinel pyramid". The pyramid tomb at Saqqara was constructed with six steps, which were then covered with white limestone. The top three levels of the pyramid are now missing and most of the limestone casing has been removed.[3]

In the interior of the pyramid three rooms would have contained Djedkare's burial. The burial chamber contained the dark grey basalt sarcophagus which held the body of the king. The canopic jars were buried in the floor of the burial chamber, to the north-east of the sarcophagus. An antechamber and a storage chamber completed the set of interior rooms. Djedkare's almost complete mummy, along with a badly broken basalt sarcophagus and a niche for the canopic chest, was discovered in the pyramid.[3] Djedkare died at ca 50–60 years of age.[20]

To the east of the pyramid Djedkare's mortuary temple was laid out. The east facade of the mortuary temple featured to massive stone structures which resemble the later pylons. The mortuary temple is connected via a causeway to a valley temple. An interesting structure associated with Djedkare's pyramid is the so-called "Pyramid of the Unknown Queen". This pyramid complex lies at the south-east corner of Djedkare's complex.[3]

See also

- List of Egyptian pyramids

- List of megalithic sites

References

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, pp.405

- ↑ Peter Clayton, Chronicle of the Pharaohs, Thames and Hudson, 1994. p.61

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 M. Verner, The Pyramids, 1997

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Dodson, Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, 2004

- ↑ Edward Brovarski, The Senedjemib Complex, Retrieved from the Giza digital library Giza Mastabas 7

- ↑ Ann Macy Roth, Giza Mastabas Volume 6, A Cemetery of Palace Attendants: Including G 2084–2099, G 2230+2231, and G 2240

- ↑ Ann Macy Roth, Giza Mastabas Volume 6

- ↑

- ↑ Porter and Moss, Volume III: Memphis

- ↑ E. Wente, Letters from Ancient Egypt, 1990, pg 18-20

- ↑ Edward Brovarski, Giza Mastabas Vol. 7: The Senedjemib Complex

- ↑ Karl Richard Lepsius: Denkmaler Abtheilung II Band III Available online see p. 2, p. 39

- ↑ Nigel Strudwick, Ronald J. Leprohon, Texts from the pyramid age, [retrieved from google books]

- ↑ Grimal, A history of ancient Egypt, 1992, pg 79 [retrieved from google books]

- ↑ E. Wente, Letters from Ancient Egypt, 1990, pg 20-21

- ↑ Pierre Tallet, Ayn Sukhna and Wadi el-Jarf: Two newly discovered pharaonic harbours on the Suez Gulf. (PDF file) British Museum Studies in Ancient Egypt and Sudan 18 (2012): 147–68

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Verner, p.406

- ↑ Verner, p.410

- ↑ ASAE, 47 (1947), p.98

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, 2001, pp. 410

Bibliography

- Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, pp. 405–410 (coverage of Djedkare Isesi's reign)