Diving suit

A diving suit is a garment or device designed to protect a diver from the underwater environment. A diving suit may also incorporate a breathing gas supply (i.e. Standard diving dress or atmospheric diving suit).[1] but in most cases applies only to the environmental protective covering worn by the diver. The breathing gas supply is usually referred to separately. There is no generic term for the combination of suit and breathing apparatus alone. It is generally referred to as diving equipment or dive gear along with any other equipment necessary for the dive.

History

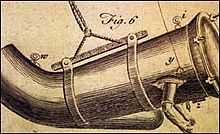

The first diving dress designs appeared in the early 18th century. Two English inventors developed the first pressure-proof diving suits in the 1710s. John Lethbridge built a completely enclosed suit to aid in salvage work. It consisted of a pressure-proof air-filled barrel with a glass viewing hole and two watertight enclosed sleeves.[2] This suit gave the diver more maneouverability to accomplish useful underwater salvage work.

After testing this machine in his garden pond (specially built for the purpose) Lethbridge dived on a number of wrecks: four English men-of-war, one East Indiaman (both English and Dutch), two Spanish galleons and a number of galleys. He became very wealthy as a result of his salvages. One of his better-known recoveries was on the Dutch Slot ter Hooge, which had sunk off Madeira with over three tons of silver on board.[3]

At the same time, Andrew Becker created a leather-covered diving suit with a helmet featuring a window. Becker used a system of tubes for inhaling and exhaling, and demonstrated his suit in the River Thames, London, during which he remained submerged for an hour.

German-born British engineer Augustus Siebe developed the standard diving dress in the 1830s. Expanding on improvements already made by another engineer, George Edwards, Siebe produced his own design - a helmet fitted to a full length watertight canvas diving suit. Later dresses were made with waterproofed canvas invented by Charles Mackintosh. From the late 1800s and throughout most of the 20th century, most Standard Dresses consisted of a solid sheet of rubber between layers of tan twill.[4]

Diving suits made of rubber were used in World War II by Italian frogmen who found them indispensable in their use. They were made by Pirelli and patented in 1951.[5]

Modern diving suits

Modern diving suits can be divided into two kinds:

- "soft" or ambient pressure diving suits - examples are wetsuits, dry suits, semi-dry suits and dive skins

- "hard" or atmospheric pressure diving suits - an armored suit that permits a diver to remain at atmospheric pressure whilst operating at depth where the water pressure is high.

Ambient pressure suits

Ambient pressure suits are a form of exposure protection protecting the wearer from the cold. They also provide some defence from abrasive and sharp objects as well as potentially harmful underwater life. They do not protect divers from the pressure of the surrounding water or resulting barotrauma and decompression sickness.

There are five main types of ambient pressure diving suits

- dive skins

- wetsuits

- semi-dry suits

- drysuits

- hot water suits

Apart from hot water suits, these types of suit are not exclusively used by divers but are often used for thermal protection by people engaged in other water sports activities such as surfing, sailing, powerboating, windsurfing, kite surfing, waterskiing, caving and swimming.

The suits are often made from Neoprene, heavy-duty fabric coated with rubber, or PVC.

Added buoyancy, created by the volume of the suit, is a side effect of diving suits. Sometimes a weightbelt must be worn to counteract this buoyancy. Some drysuits have controls allowing the suit to be inflated to reduce "squeeze" caused by increasing pressure; they also have vents allowing the excess air to be removed from the suit on ascent.

Dive skins

Dive skins are used when diving in water temperatures above 25 °C (77 °F). They are made from spandex or Lycra and provide little thermal protection, but do protect the skin from jellyfish stings, abrasion and sunburn. This kind of suit is also known as a 'Stinger Suit'. Some divers wear a dive skin under a wetsuit, which allows easier donning and (for those who experience skin problems from neoprene) provides additional comfort.

The "Dive Skin" was originally invented to protect scuba divers in Queensland Australia against the "Box" jellyfish (Chironex Fleckeri)

In 1978, Tony Farmer was a swimsuit designer and manufacturer who owned a business called "Daring Designs". Besides swimwear he also did underwear and aerobic wear which included a full suit in Lycra/Spandex. He became a scuba diver and that was the catalyst to the invention of the "dive skin" as we know it today.

The "Surf Life Savers" in Queensland used to wear 2nd hand panty hose as protection during the "box" jellyfish season. The nematocysts (stings) of the jellyfish are so small that a thin layer of panty hose is enough to prevent the stinger from penetrating deep enough into the epidermis to get the venom into the blood stream. Tony thought this was a little embarrassing for these 'bronzed' Aussies to be wearing on the beach and thought that his one-piece Lycra suit would be far more suitable and effective.

Wetsuits

Wetsuits are relatively inexpensive, simple, Neoprene suits that are typically used where the water temperature is between 10 and 25 °C (50 and 77 °F). The foamed neoprene of the suit thermally insulates the wearer.[6][7] Although water can enter the suit, a close fitting suit prevents excessive heat loss because little of the water warmed inside the suit escapes from the suit to be replaced by cold water, a process referred to as "flushing".

Proper fit is critical for warmth. A suit that is too loose will allow too much water to circulate over the diver's skin, robbing body heat. A suit that is too tight is very uncomfortable and can impair circulation at the neck, a very dangerous condition which can cause blackouts. For this reason, many divers choose to have wetsuits custom-tailored instead of buying them "off-the-rack." Many companies offer this service and the cost is often comparable to an off-the-rack suit.

Wetsuits are limited in their ability to provide warmth by two factors: the wearer is still exposed to some amount of water, and the insulating Neoprene can only be made to a certain thickness before it becomes impractical to don and wear. The thickest commercially-available wetsuits are usually 10mm thick. Other common thicknesses are 7mm, 5mm, 3mm, and 1mm. A 1mm suit provides very little warmth and is usually considered a dive skin, rather than a wetsuit.

Semi-dry suits

Semi-dry suits are effectively a thick wetsuit with better-than-usual seals at wrist, neck and ankles. They are used typically where the water temperature is between 10 and 20 °C (50 and 68 °F). The seals limit the volume of water entering and leaving the suit. The wearer gets wet in a semi-dry suit but the water that enters is soon warmed up and does not leave the suit readily, so the wearer remains warm. The trapped layer of water does not add to the suit's insulating ability. Any residual water circulation past the seals still causes heat loss. But semi-dry suits are cheap and simple compared to dry suits. They are made from thick Neoprene, which provides good thermal protection. They lose buoyancy and thermal protection as the trapped gas bubbles in the Neoprene compress at depth. Semi-dry suits are made in various configurations including a single piece or two pieces, made of 'long johns' and a separate 'jacket'. Semi dry suits do not usually include boots or gloves, so a separate pair of neoprene insulating boots and gloves are worn.

Drysuits

_prepare_to_dive.jpg)

Drysuits[8][9][10] are used typically where the water temperature is between −2 and 15 °C (28 and 59 °F). Water is prevented from entering the suit by seals at the neck and wrists; also, the means of getting the suit on and off (typically a zipper) is waterproof. The suit insulates the wearer in one of two main ways: by maintaining pockets of air between the body and the cold water in standard air-containing fabric undergarments beneath the suit (in exactly the way that insulation garments work in air) or via (additional) foamed-neoprene material which contains insulative air, which may be incorporated into the outside of the drysuit itself.

Both fabric and neoprene drysuits have advantages and disadvantages: a fabric drysuit is more adaptable to varying water temperatures because different garments can be layered underneath. However, they are quite bulky and this causes increased drag and swimming effort. Additionally, if a fabric drysuit malfunctions and floods, it loses nearly all of its insulating properties. Neoprene drysuits are comparatively streamlined like wetsuits, but in some cases do not allow garments to be layered underneath and are thus less adaptable to varying temperatures. An advantage of this construction is that even it if floods completely, it essentially becomes a wetsuit and will still provide a degree of insulation.

Special drysuits (typically made of strong rubberised fabric) are worn by commercial divers who work in contaminated environments such as sewage or hazardous chemicals. The drysuit has integral boots and is sealed to a diving helmet and dry gloves to prevent any exposure to the hazardous material.

For additional warmth, some drysuit users inflate their suits with argon, an inert gas which has superior thermal insulating properties compared to air.[11] The argon is carried in a small cylinder, separate from the diver's breathing gas. This arrangement is frequently used when the breathing gas contains helium, which is a very poor insulator in comparison with other breathing gases.

Hot water suits

Hot water suits are used in cold water commercial surface supplied diving.[12] An insulated pipe in the umbilical line, which links the diver to the surface support, carries the hot water from a heater on the surface down to the suit. The diver controls the flow rate of the water from a valve near his waist, allowing him to vary the warmth of the suit in response to changes in environmental conditions and workload. Pipes inside the suit transport the water to the limbs, chest, and back. Special boots, gloves, and hood are worn. These suits are normally made of foamed neoprene and are similar to wetsuits in construction and appearance, but they do not fit as closely by design. The wrists and ankles of the suit are open, allowing water to flush out of the suit as it is replenished with fresh hot water from the surface.[13]

Hot water suits are often employed for extremely deep dives when breathing mixes containing helium are used. Helium conducts heat much more efficiently than air, which means that the diver will lose large quantities of body heat through the lungs when breathing it. This fact compounds the risk of hypothermia already present in the cold temperatures found at these depths. Under these conditions a hot water suit is a matter of survival, not comfort. Just as an emergency backup source of breathing gas is required, a backup water heater is also an essential precaution whenever dive conditions warrant a hot water suit. If the heater fails and a backup unit cannot be immediately brought online, a diver in the coldest conditions can die within minutes; depending on decompression obligations, bringing the diver directly to the surface could prove equally deadly.[13]

Heated water in the suit forms an active insulation barrier to heat loss, but the temperature must be regulated within fairly close limits. If the temperature falls below about 32°C, hypothermia can result, and temperatures above 45°C can cause burn injury to the diver. The diver may not notice a gradual change in inlet temperature, and in the early stages of hypo- or hyperthermia, may not notice the deteriorating condition.[13]

The suit is loose fitting to allow unimpeded water flow. This causes a large volume of water (13 to 22 litres) to be held in the suit, which can impede swimming due to the added inertia.[13]

When controlled correctly, the hot water suit is safe, comfortable and effective, and allows the diver adequate control of thermal protection, however hot water supply failure can be life-threatening.[13]

Diving suit combinations

A "shortie" wetsuit may be worn over a full wetsuit for added warmth. Some vendors sell a very similar item and refer to it as a 'core warmer' when worn over another wetsuit. A "skin" may also be worn under a wetsuit. This practice started with divers (of both sexes) wearing women's body tights under a wetsuit for extra warmth and to make donning and removing the wetsuit easier. A "skin" may also be used instead of an undersuit beneath a drysuit in temperatures where a full undersuit is not necessary.

Atmospheric diving suits

An atmospheric diving suit is a small one-man articulated submersible of anthropomorphic form which resembles a suit of armour, with elaborate pressure joints to allow articulation while maintaining an internal pressure of one atmosphere.

These can be used for very deep dives for long periods without the need for decompression, and eliminate the majority of physiological dangers associated with deep diving. Divers do not even need to be skilled swimmers. Mobility and dexterity are usually restricted by mechanical constraints, and the ergonomics of movement are problematic.

See also

- Timeline of underwater technology

- Space suit

- Standard diving dress

- Atmospheric diving suit

References

- ↑ Diving suit term: may include air supply system

- ↑ John Lethbridge, inventor from Newton Abbot, BBC website

- ↑ Acott, C. (1999). "A brief history of diving and decompression illness.". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal 29 (2). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Acott, C. (1999). "JS Haldane, JBS Haldane, L Hill, and A Siebe: A brief resume of their lives.". South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society Journal 29 (3). ISSN 0813-1988. OCLC 16986801. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ The first rubber wet suit made by Pirelli and patented in 1951

- ↑ US Navy Diving Manual, 6th revision. United States: US Naval Sea Systems Command. 2006. Retrieved 2008-04-24.

- ↑ Fulton, HT; Welham, W; Dwyer, JV; Dobbins, RF (1952). "Preliminary Report on Protection Against Cold Water". US Naval Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-RR-5-52. Retrieved 2008-04-25.

- ↑ Piantadosi, C. A.; Ball D. J.; Nuckols M. L.; Thalmann E. D. (1979). "Manned Evaluation of the NCSC Diver Thermal Protection (DTP) Passive System Prototype". US Naval Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-13-79. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ Brewster, D. F.; Sterba J. A. (1988). "Market Survey of Commercially Available Dry Suits". US Naval Experimental Diving Unit Technical Report. NEDU-3-88. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ Nishi, R. Y. (1989). "Proceedings of the DCIEM Diver Thermal Protection Workshop". Defence and Civil Institute of Environmental Medicine, Toronto, CA. DCIEM 92-10. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ Nuckols ML, Giblo J, Wood-Putnam JL. (September 15–18, 2008). "Thermal Characteristics of Diving Garments When Using Argon as a Suit Inflation Gas.". Proceedings of the Oceans 08 MTS/IEEE Quebec, Canada Meeting (MTS/IEEE). Retrieved 2009-03-02.

- ↑ Mekjavić B, Golden FS, Eglin M, Tipton MJ (2001). "Thermal status of saturation divers during operational dives in the North Sea". Undersea Hyperb Med 28 (3): 149–55. PMID 12067151. Retrieved 2008-05-05.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Bevan, John, ed. (2005). "Section 5.4". The Professional Divers's Handbook (second ed.). 5 Nepean Close, Alverstoke, GOSPORT, Hampshire PO12 2BH: Submex Ltd. p. 242. ISBN 978-0950824260.

External links

|

- Experimental Dive Suit Flies Navy Divers Where None Have Gone Before - Development of a 1-atmosphere diving suit.

- Scuba America Historical Center - The development of the first wetsuit.

- LA Times: Surfing whodunit - The history of the wetsuit.

- Wetsuit Guide

- Diving Equipment Guide

- ADS database

- History of Diving Museum