Diversity combining

Diversity combining is the technique applied to combine the multiple received signals of a diversity reception device into a single improved signal.

Various techniques

Various diversity combining techniques can be distinguished:

- Equal-gain combining: All the received signals are summed coherently.

- Maximal-ratio combining is often used in large phased-array systems: The received signals are weighted with respect to their SNR and then summed. The resulting SNR yields

where

where  is SNR of the received signal

is SNR of the received signal  .

.

- Switched combining: The receiver switches to another signal when the currently selected signal drops below a predefined threshold. This is also often called "Scanning Combining".

- Selection combining: Of the N received signals, the strongest signal is selected. When the N signals are independent and Rayleigh distributed, the expected diversity gain has been shown to be

, expressed as a power ratio.[1] Therefore, any additional gain diminishes rapidly with the increasing number of channels. This is a more efficient technique than switched combining.

, expressed as a power ratio.[1] Therefore, any additional gain diminishes rapidly with the increasing number of channels. This is a more efficient technique than switched combining.

Sometimes more than one combining technique is used – for example, lucky imaging uses selection combining to choose (typically) the best 10% images, followed by equal-gain combining of the selected images.

Other signal combination techniques have been designed for noise reduction and have found applications in single molecule biophysics, chemometrics among other disciplines.[2]

Timing Combining

When the focus is on the wireless transmission of longer signal sequences, such as for example Ethernet packets, specific performance characteristics regarding diversity gain on a parallel redundant wireless transmission system can be observed. For "Timing Combining", data packets are redundantly and simultaneously sent over parallel paths. On the receiving side, out of the branches the first arriving packet is selected and immediately processed towards the end application. Further copies of the packet -if arriving- are discarded. This type of postdetection combiner was named “Timing Combiner”, since a significant performance improvement is gained through the immediate processing of the first arriving packet.[3]

Switched combining two-way radio example

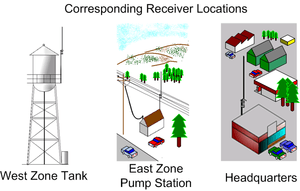

In land-mobile radio, where vehicle-mounted and hand-held radios communicate with a base station radio over a single frequency, space diversity is achieved by having several receivers at different sites. Diversity combining, or voting, in two-way radio systems is a method for improving talk-back range from walkie-talkie and vehicular mobile radios.[4]

The receivers are connected to a device referred to as a voting comparator or voter.

The voting comparator performs an evaluation of all received signals and picks the most usable received signal.[5] In repeater systems, the voted signal is retransmitted. In simplex systems, it goes to the console speaker at the base station. Audio from a receiver that is not voted is ignored. Voting comparators in analog FM systems can switch between receivers in tenths- or hundredths-of-a-second, (faster than one syllable). So long as an intelligible signal gets to a single receiver in the system, the repeated audio, or audio sent to the console speaker, would be intelligible.

In this arrangement, receivers at remote sites are connected to the voting comparator by private telephone lines, a channel in a D4 channel bank on a DS1, or an analog microwave baseband channel.

How signals are evaluated

The earliest voting comparators relied on a tone encoded on a separate audio path, requiring each receiver site to have a 4-wire circuit or two audio paths. The pitch of the tone changed to represent the received signal level, or FM receiver limiter voltage, at the remote receiver. This worked poorly because it did not account for microwave baseband noise or noisy telephone company circuits.

Newer voting comparators compare signal-to-noise ratio at the voting comparator, accounting for end-to-end noise, bad phone lines, poor level discipline, as well as the best diversity reception path.

Walkie-talkie talk-back range

When communicating with hand-held radios (walkie-talkies), base stations generally talk out further than they can receive. Voting among several receivers at different sites increases the probability that one of the receivers will acquire a usable signal from two-way radios in a system.

Interference reduction

Diversity combining reduces one possible single-point failure: any single receiver failure, or local interference to a single receiver, will not block reception on the entire system. Equipment sites can host many radio transmitters and receivers.[6] A single site is subject to local, site-specific interfering signals. These interfering signals may come and go as transmitters switch on and off.

A potential problem with receivers located at high-elevation receiver sites is that they may acquire signals from distant counties, prefectures, or other provinces. These unwanted, distant signals can be stronger than desired signals from local walkie-talkies.[7] The distant signals may block local weak signals in some cases. Having several receive sites increases the probability that one of the sites will receive the local signal in the presence of a distant, undesired one.[8] Selective calling can eliminate users having to listen to the audio of distant signals even though the distant signals are within receive range of one or more receivers.

Coverage

A minimum of 95% coverage is cited in literature for critical or emergency service two-way radio systems.[9] One definition of system coverage is Telecommunications Industry Association (TIA) TSB-88A standard.[10]

Vote-lock or vote-and-hold option

The majority of installations using diversity combining equipment continually evaluate the best received signal against all other signals. Throughout the length of a received transmission, the comparator may switch receivers as often as every few tenths of a second. As a walkie-talkie user causes a signal fade by turning their head, or a passing tractor-trailer rig blocks their signal at the voted receive site, the combining unit rapidly changes to a different receiver.[11]

In some installations, diversity combining equipment is configured to lock on a receiver. For example, in some rural, regional coverage systems, the receivers each cover a unique geographic area. There is not much overlap. If the system consisted of two sites, north and south, it would pick the better of the two and remain locked on that receiver until the transmission ended.[12] This works better with mobile radios because their signal strengths tend to be steady.[13]

In some cases this vote-and-hold is used to steer transmitter selection. Consider the case of a regional system with two base stations: north and south. If the diversity combining equipment votes "north," the next time the dispatcher presses the transmit button, the north transmitter will key. Called transmitter steering, this is supposed to automate transmitter selection in systems where more than one transmitter site is available. In some instances it doesn't work well.[14]

In mobile data systems, the vote lock option is preferred because constant switching between receivers causes lost data packets. The diversity combining equipment switches fast enough that syllables are not lost but not fast enough that bits are not lost. Mobile data systems usually originate with modems in mobile radios. Mobile radios usually produce solid signals into more than one receive site, so the signal strengths are strong enough for vote locking to work well.[15]

References

- ↑ D.G. Brennan, "Linear diversity combining techniques," Proc. IRE, vol.47, no.1, pp.1075–1102, June 1959

- ↑ Mashaghi et al. Noise reduction by signal combination in Fourier space applied to drift correction in optical tweezers, Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 115103 (2011)

- ↑ Rentschler, M.; Laukemann, P., "Performance analysis of parallel redundant WLAN," Emerging Technologies & Factory Automation (ETFA), 2012 IEEE 17th Conference on , vol., no., pp.1,8, 17-21 Sept. 2012

- ↑ To confirm the use of the word voting to describe this equipment, see US Patent and Trademark Office patent ID 4531235 and 5884192 "Diversity Combining for Antennas."

- ↑ "Section V: Conclusions," The California Highway Patrol Communications Technology Research Project on 800 MHz, 80-C477, (Sacramento, California: Department of General Services, Communications Technology Division, 1982,) pp. V-6.

- ↑ For example, one specific equipment site is described as having six base stations and many receivers. See: "3.1.3 Draper Lake Radio Site," Trunked Radio System: Request For Proposals, (Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Oklahoma City Municipal Facilities Authority, Public Safety Capital Projects Office, 2000) pp. 56.

- ↑ One rule of thumb is that a walkie-talkie transmitter produces one-tenth (-10 db) to one-hundredth (-20 db) of the signal levels of vehicular radios at the base station receiver.

- ↑ "Evaluating Regional Alternatives: Site Selection," Planning Emergency Medical Communications: Volume 2, Local/Regional Level Planning Guide, (Washington, D.C.: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, US Department of Transportation, 1995) pp. 52-55.

- ↑ "Evaluating Regional Alternatives: Site Selection," Planning Emergency Medical Communications: Volume 2, Local/Regional Level Planning Guide, (Washington, D.C.: National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, US Department of Transportation, 1995) pp. 52. A professional consultant should help in coverage definitions for engineered systems because "95% coverage" can be interpreted many different ways.

- ↑ Coverage definitions for engineered systems are described in California EMS Communications Plan: Final Draft, (Sacramento, California: State of California EMS Authority, September 2000), and, "Glossary," Arizona Phase II Final Report: Statewide Radio Interoperability Needs Assessment, (Phoenix, Arizona: Macro Corporation and The State of Arizona, 2004), pp. 165.

- ↑ For one description of a system in operation, see: "2.1 Mobile Radio System," San Rafael Police Radio Committee: Report to Mayor and City Council, (San Rafael, California: City of San Rafael, 1995,) pp. 4.

- ↑ For a discussion of vote locking versus conventional voting, see: "Section V: Conclusions," The California Highway Patrol Communications Technology Research Project on 800 MHz, 80-C477, (Sacramento, California: Department of General Services, Communications Technology Division, 1982,) pp. V-6. The report says California Highway Patrol does not use vote locking in Los Angeles, a very congested radio environment. In some interference conditions, vote locking can produce poor results. The first voted site is sometimes not the best site. Some sites have elevated ambient noise levels causing them to continually be voted last, even though they produce marginally better audio and their ability to maintain a path to the mobile over a long transmission may be better.

- ↑ An extreme case: one California study describes a field test where the received signal level from a 90-watt, 42 MHz. mobile radio dropped from 45 microvolts (a solid signal) to nothing in one driving mile of road. See: "Section II: Radio Propagation Studies," The California Highway Patrol Communications Technology Research Project on 800 MHz, 80-C477, (Sacramento, California: Department of General Services, Communications Technology Division, 1982,) pp. V-6.

- ↑ The existence of vote-and-hold and its use in transmitter steering can be confirmed by reading, "Section V: Conclusions," The California Highway Patrol Communications Technology Research Project on 800 MHz, 80-C477, (Sacramento, California: Department of General Services, Communications Technology Division, 1982,) pp. V-6.

- ↑ Service manuals for diversity combining equipment designed for use with mobile data will describe this in detail.