Distilled beverage

A distilled beverage, spirit, liquor, or hard liquor is an alcoholic beverage produced by distillation of a mixture produced from alcoholic fermentation, such as wine. This process purifies it and removes diluting components like water, for the purpose of increasing its proportion of alcohol content (commonly known as alcohol by volume, ABV).[1] As distilled beverages contain more alcohol they are considered "harder" – in North America, the term hard liquor is used to distinguish distilled beverages from undistilled ones, which are implicitly weaker.

As examples, this does not include beverages such as beer, wine, and cider, as they are fermented but not distilled. These all have relatively low alcohol content, typically less than 15%. However, brandy is a spirit, is distinct as a drink from wine (due to distillation), and has an ABV over 35%. Other examples of common distilled beverages include vodka, gin, tequila, Singani, rum, whisky, as well as eau de vie (Fruit Brandy or Schnapps), baijiu, soju, aguardiente, pálinka, fernet, cachaça,and slivovitz.

Nomenclature

The term spirit refers to a distilled beverage that contains no added sugar and has at least 20% alcohol by volume (ABV). Popular spirits include brandy, fruit brandy (also known as eau de vie or Schnapps), gin, Singani, rum, tequila, vodka, baijiu and whisky.

Distilled beverages bottled with added sugar and added flavorings, such as Grand Marnier, Frangelico, and American Schnapps, are known instead as liqueurs. In common usage, the distinction between spirits and liqueurs is widely unknown or ignored; as a consequence, in general, all alcoholic beverages other than beer and wine are referred to as spirits.

Beer and wine, which are not distilled beverages, are limited to a maximum alcohol content of about 20% ABV, as most yeasts cannot reproduce when the concentration of alcohol is above this level; as a consequence, fermentation ceases at that point.

Etymology

The origin of "liquor" and its close relative "liquid" was the Latin verb liquere, meaning "to be fluid". According to the Oxford English Dictionary, an early use of the word in the English language, meaning simply "a liquid", can be dated to 1225. The first use the OED mentions of its meaning "a liquid for drinking" occurred in the 14th century. Its use as a term for "an intoxicating alcoholic drink" appeared in the 16th century.

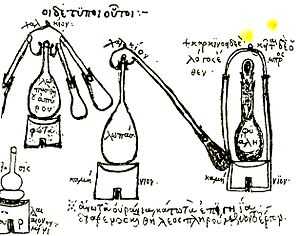

The term "spirit" in reference to alcohol stems from Middle Eastern alchemy. These alchemists were more concerned with medical elixirs than with transmuting lead into gold. The vapor given off and collected during an alchemical process (as with distillation of alcohol) was called a spirit of the original material.

History of distillation

Precursors

The first clear evidence of distillation comes from Greek alchemists working in Alexandria in the 1st century AD,[5] although the Chinese may have independently developed the process around the same time.[6] Distilled water was described in the 2nd century AD by Alexander of Aphrodisias.[7] The Alexandrians were using a distillation alembic or still device in the 3rd century AD.

The medieval Arabs learned the distillation process from the Alexandrians and used it extensively, but there is no evidence that they distilled alcohol.[5]

Freeze distillation, the "Mongolian still", is known to have been in use in Central Asia sometime in the early Middle Ages. This technique involves freezing the alcoholic beverage and then removing the ice. The freezing technique had limitations in geography and implementation and so was not widely used. A notable drawback of this technique is that it concentrates, rather than reduces, toxins such as methanol and fusel oil.[8]

True distillation

The earliest evidence of true distillation of alcohol comes from the School of Salerno in southern Italy during the 12th century.[9][10] Again, the Chinese may not have been far behind, with archaeological evidence indicating the practice of distillation began during the 12th century Jin or Southern Song dynasties.[6] A still has been found at an archaeological site in Qinglong, Hebei, dating to the 12th century.[6]

Fractional distillation was developed by Tadeo Alderotti in the 13th century.[11] The production method was written in code, suggesting that it was being kept secret.

In 1437, "burned water" (brandy) was mentioned in the records of the County of Katzenelnbogen in Germany.[12] It was served in a tall, narrow glass called a Goderulffe.

Paracelsus experimented with distillation. His test was to burn a spoonful without leaving any residue. Other ways of testing were to burn a cloth soaked in it without actually harming the cloth. In both cases, to achieve this effect, the alcohol had to be at least 95 percent, close to the maximum concentration attainable through distillation (see purification of ethanol).

Claims upon the origin of specific beverages are controversial, often invoking national pride, but they are plausible after the 12th century AD, when Irish whiskey and German brandy became available. These spirits would have had a much lower alcohol content (about 40% ABV) than the alchemists' pure distillations, and they were likely first thought of as medicinal elixirs. Consumption of distilled beverages rose dramatically in Europe in and after the mid-14th century, when distilled liquors were commonly used as remedies for the Black Death. Around 1400, methods to distill spirits from wheat, barley, and rye beers, a cheaper option than grapes, were discovered. Thus began the "national" drinks of Europe: jenever (Belgium and the Netherlands), gin (England), Schnaps (Germany), grappa (Italy), horilka (Ukraine), akvavit/snaps (Scandinavia), vodka (Russia and Poland), ouzo (Greece), rakia (the Balkans), and poitín (Ireland). The actual names emerged only in the 16th century, but the drinks were well known prior to then.

Modern distillation

.jpg)

Except for the invention of the continuous still in the 19th century, the basic process of distillation has not changed since the eighth century. Many changes in the methods used to prepare organic material for the still have occurred, and the ways the distilled beverage is finished and marketed have changed. Knowledge of the principles of sanitation and access to standardised yeast strains have improved the quality of the base ingredients. Larger, more efficient stills reduce waste and produce more beverage in smaller areas.

Chemists have discovered the scientific principles behind aging, and have devised ways to accelerate aging without introducing harsh flavors. Modern filters have allowed distillers to remove unwanted residues and produce smoother finished products. Most of all, marketing has developed a worldwide market for distilled beverages among populations that previously did not drink spirits.

Government regulation

In some jurisdictions in the United States, it is legal for unlicensed individuals to make their own beer and wine. However, it is illegal to distill beverage alcohol without a license anywhere in the US. In some jurisdictions, it is also illegal to sell a still without a license.

It is legal to distill beverage alcohol as a hobby for personal use in some countries, including Italy, New Zealand, Netherlands, and (to a limited degree) the United Kingdom. In those jurisdictions where it is illegal to distill beverage alcohol, some people circumvent those laws by purporting to distill alcohol for fuel but consuming the product. It is important not to confuse ethanol, which is a type of alcohol used for both beverages and fuel, with methanol, which is a different alcohol fuel that is much more poisonous. Methanol is produced as a by-product of beverage distillation, but only in small amounts that are ordinarily separated out during the beverage production process. Methanol can cause blindness or death if a sufficient quantity is ingested.

Microdistilling

Microdistilling (also known as craft distilling) as a trend began to develop in the United States following the emergence and immense popularity of microbrewing and craft beer in the last decades of the 20th century. It is different from megadistilling in the quantity and quality of output.

Flammability

Liquor that contains 40% ABV (80 US proof) will catch fire if heated to about 26 °C (79 °F) and if an ignition source is applied to it. (This is called its flash point.[13] The flash point of pure alcohol is 16.6 °C (61.9 °F), less than average room temperature.[14])

The flash points of alcohol concentrations from 10% ABV to 96% ABV are:[15]

- 10% — 49 °C (120 °F) — ethanol-based water solution

- 12.5% — about 52 °C (126 °F) — wine[16]

- 20% — 36 °C (97 °F) — fortified wine

- 30% — 29 °C (84 °F)

- 40% — 26 °C (79 °F) — typical vodka, whisky or brandy

- 50% — 24 °C (75 °F) — strong whisky

- 60% — 22 °C (72 °F) — normal tsikoudia(called mesoraki(middle raki))

- 70% — 21 °C (70 °F) — absinthe, Slivovitz

- 80% — 20 °C (68 °F)

- 90% or more — 17 °C (63 °F) — neutral grain spirit

Beverages with low concentrations of alcohol will burn if sufficiently heated and an ignition source (such as an electric spark or a match) is applied to them. For example, the flash point of ordinary wine containing 12.5% alcohol is about 52 °C (126 °F).[16]

Serving

Distilled beverages can be served:

- Neat — at room temperature without any additional ingredient(s)[17]

- Up — shaken or stirred with ice, strained, and served in a stemmed glass.

- On the rocks — over ice cubes

- Blended or frozen — blended with ice

- With a simple mixer, such as club soda, tonic water, juice, or cola

- As an ingredient of a cocktail

- As an ingredient of a shooter

- With water

- With water poured over sugar (as with absinthe)

Alcohol consumption by country

The World Health Organization measures and publishes alcohol consumption patterns in different countries. The WHO measures alcohol consumed by persons 15 years of age or older and reports it on the basis of liters of pure alcohol consumed per capita in a given year in a country.[18] (See List of countries by alcohol consumption.)

See also

- Absinthe

- Akvavit

- Aguardiente

- Alcoholic beverage

- Arak

- Arrack

- Baijiu / Shōchū / Soju

- Brandy

- Cachaça

- Eau de vie

- Er guo tou

- Fenny

- Freeze distillation

- Gin (and Jenever)

- Horilka

- Liquor store

- List of beverages

- Mezcal

- Moonshine

- Neutral grain spirit

- Pálinka

- Pisco

- Poitín

- Rakı

- Rakia

- Rum

- Rượu_đế

- Schnapps

- Slivovitz

- Vodka

- Whisky

- Tsikoudia

- Tsipouro

References

- ↑ Britannica Online Encyclopedia: distilled spirit/distilled liquor

- ↑ E. Gildemeister and Fr. Hoffman, translated by Edward Kremers (1913). The Volatile Oils 1. New York: Wiley. p. 203.

- ↑ Bryan H. Bunch and Alexander Hellemans (2004). The History of Science and Technology. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt. p. 88. ISBN 0-618-22123-9.

- ↑ Marcelin Berthelot Collection des anciens alchimistes grecs (3 vol., Paris, 1887–1888, p.161)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Forbes, Robert James (1970). A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Stephen G. Haw (10 September 2012). "Wine, women and poison". Marco Polo in China. Routledge. pp. 147–148. ISBN 978-1-134-27542-7.

The earliest possible period seems to be the Eastern Han dynasty... the most likely period for the beginning of true distillation of spirits for drinking in China is during the Jin and Southern Song dynasties

- ↑ Taylor, F. Sherwood (1945). "The Evolution of the Still". Annals of Science 5 (3): 186. doi:10.1080/00033794500201451. ISSN 0003-3790.

- ↑ Freezing distillation extracts the water out of the substance, leaving greater relative alcohol content. Natural juices contain methanol (wood alcohol), but at low doses methanol is untoxic. A person may consume a standard bottle of wine (750mL at 12% ABV) or use freezing distillation to remove excess water, leaving 250 mL at 36% ABV without changing the amount of methanol consumed. Fusel oils are non-toxic but are typically discarded because of their unpleasant taste. Nonetheless, many whisky manufactures will add a hint of fusel oils to the main batch in order to give the whisky a rustic taste.

- ↑ Forbes, Robert James (1970). A short history of the art of distillation: from the beginnings up to the death of Cellier Blumenthal. BRILL. pp. 57, 89. ISBN 978-90-04-00617-1. Retrieved 29 June 2010.

- ↑ Sarton, George (1975). Introduction to the history of science. R. E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 145.

- ↑ Holmyard, Eric John (1990). Alchemy. Courier Dover Publications. p. 53.

- ↑ graf-von-katzenelnbogen.com, see entry at Trinkglas.

- ↑ "Flash Point and Fire Point". Retrieved March 6, 2011.

- ↑ "Material Safety Data Sheet, Section 5". Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ "Flash points of ethanol-based water solutions". Retrieved June 23, 2011.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Robert L. Wolke (5 July 2006). "Combustible Combination". Washington Post. Retrieved 27 January 2011.

- ↑ Walkart, C.G. (2002). National Bartending Center Instruction Manual. Oceanside, California: Bartenders America, Inc. p. 104. ASIN: B000F1U6HG.

- ↑ who.int

Bibliography

- Blue, Anthony Dias (2004). The Complete Book of Spirits: A Guide to Their History, Production, and Enjoyment. New York: HarperCollins Publishers. ISBN 0-06-054218-7.

- Forbes, Robert (1997). Short History of the Art of Distillation from the Beginnings up to the Death of Cellier Blumenthal. Brill Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-00617-6.

- Multhauf, Robert (1993). The Origins of Chemistry. Gordon & Breach Science Publishers. ISBN 2-88124-594-3.