Dissection

| Dissection | |

|---|---|

|

Dissection of a pregnant Rat , done in a biology class | |

|

Ginko seed in dissection, showing embryo and gametophyte. | |

| Anatomical terminology |

Dissection (from Latin dissecare "to cut to pieces";[1] also called anatomization, from Greek anatomia,[2] from ana- "up" and temnein "to cut"[3]) is the process of disassembling and observing something to determine its internal structure and as an aid to discerning the functions and relationships of its components. The term is most often used concerning the dissection of plants and animals, including humans. Human dissection is commonly practiced in the teaching of anatomy for students of medicine, while students of biology often engage in dissections of animals, but also of plants. Dissection is a medical practice utilized in pathology and forensic medicine during autopsy.[4] Vivisection is related to dissection,[5] but is done on living specimens.[6]

In biology

Dissection is usually applied to the examination of plants and animals. The term is also used in relation to mechanisms, computer programs, written materials, etc., as a synonym for terms such as reverse engineering or literary deconstruction. Dissection is usually performed by students in courses of biology, botany and anatomy and in association with medical and arts studies.

Vivisection refers to the dissection of a living animal, often for the purposes of physiological investigation and nowadays usually under heavy sedation. However, the term is no longer widely used, in part because more sophisticated techniques have superseded it for many applications. The term is now almost entirely used in a pejorative sense by those who oppose animal testing of any sort.

Dissection is often performed as a part of determining a cause of death in autopsy (on humans) and necropsy (on animals) and is an intrinsic part of forensic medicine, such as would be practiced by a coroner.

History

Classical antiquity

Human dissections were carried out by the Greek physicians Herophilus of Chalcedon and Erasistratus of Chios in the early part of the third century BC.[7] Before and after this time investigators appeared to largely limit themselves to animals.[8] Roman law forbade dissection and autopsy of the human body,[9] so physicians had to use other cadavers. Galen, for example, dissected the Barbary Macaque and other primates, assuming their anatomy was basically the same as that of humans.[10][11][12]

Islamic world

It is not known whether or not human dissections were also conducted by Arabic physicians. Islamic scholars such as Al-Ghazali expressed support for its practice.[13] It is possible that Islamic physicians may have performed dissections, including Ibn Zuhr (Avenzoar) (1091–1161) in Al-Andalus,[14] Saladin's physician Ibn Jumay during the 12th century, Abd el-Latif in Egypt c. 1200,[15] and Ibn al-Nafis in Syria and Egypt in the 13th century.[13][16][17] However, doubt remains because al-Nafis, a specialist in Islamic jurisprudence, construed dissection as un-Islamic and avoided it, citing "shari'a [the religious law] and his own 'compassion' for the human body".[18]

Tibet

Tibetan medicine had developed a rather sophisticated knowledge of anatomy and physiology, which was acquired from their long-standing experience with human dissection. Tibetans out of necessity, had long ago adopted the practice of celestial burial (also Sky burial) because of Tibet's harsh terrain in most of the year and deficit of wood for cremation. This form of Sky burial, still practiced, begins with a ritual dissection of the deceased, and then followed by the feeding of the parts to Vultures on the hill tops. Over time, anatomical knowledge found its way into Ayurveda and to a lesser extent into China. As result, Tibet has become a home of the Buddhist medical centers Chogppori and Menchikhang (or Menhang), between the twelfth to sixteenth century A.D., where monks came to study even from foreign countries.

Christian Europe

Unlike pagan Rome, Christian Europe did not exercise a universal prohibition of the dissection and autopsy of the human body and such examinations were carried out regularly from at least the 13th century.[8][19][20] It has even been suggested that Christian theology contributed significantly to the revival of human dissection and autopsy by providing a new socio-religious and cultural context in which the human cadaver was no longer seen as sacrosanct.[8]

Throughout history, the dissection of human cadavers for medical education has experienced various cycles of legalization and proscription in different countries. Anatomization has even been ordered as a form of punishment (as, for example, in 1805 at Massachusetts to James Halligan and Dominic Daley after their public hanging). An edict of the 1163 Council of Tours, and an early 14th century decree of Pope Boniface VIII have mistakenly been identified as prohibiting dissection and autopsy,[21][22] but no universal prohibition of dissection or autopsy was exercised during the Middle Ages. Rather, the era witnessed the revival of an interest in medical studies, and a renewal in human dissection and autopsy.[23] Some European countries began legalizing the dissection of executed criminals for educational purposes in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, and Mondino de Liuzzi carried out the first recorded public dissection around 1315. Vesalius in the 16th century carried out numerous dissections in the process of performing some of the most extensive anatomical investigations up to his time, but was attacked frequently by other physicians for his disagreement with Galen's studies of human anatomy. For many years it was assumed that Vesalius's pilgrimage to Palestine was an escape from pressures of the Inquisition brought as a result of his work with cadavers. Today this is generally considered to be without foundation and is dismissed by modern biographers.[24]

The Catholic church is known to have ordered an autopsy on conjoined twins Joana and Melchiora Ballestero in Hispanola in 1533 to determine whether they shared a soul. They found that there were two distinct hearts, and hence two souls, based on the ancient Greek philosopher Empedocles, who believed the soul resided in the heart.[25]

England

In England, dissection remained entirely prohibited until the 16th century, when a series of royal edicts gave specific groups of physicians and surgeons some limited rights to dissect cadavers. The permission was quite limited: by the mid-18th century, the Royal College of Physicians and Company of Barber-Surgeons were the only two groups permitted to carry out dissections, and had an annual quota of ten cadavers between them. As a result of pressure from anatomists, especially in the rapidly growing medical schools, the Murder Act 1752 allowed the bodies of executed murderers to be dissected for anatomical research and education. By the 19th century this supply of cadavers proved insufficient, however, due to both the continuing expansion of medical schools, and the creation of a number of private medical schools, which lacked legal access to cadavers. A thriving black market arose in cadavers and body parts, leading to the creation of an entire profession of body-snatcher, and even more extremely, the infamous Burke and Hare murders in 1828, when 16 people were murdered in order to sell their cadavers to anatomists. The resulting public outcry largely led to the passage of the Anatomy Act 1832, which greatly increased the legal supply of cadavers for dissection. (See also: History of anatomy in the 19th century.)[26]

By the 21st century, the availability of interactive computer programs and changing public sentiment led to renewed debate on the use of cadavers in medical education. The Peninsula College of Medicine and Dentistry in the UK, founded in 2000, became the first modern medical school to carry out its anatomy education without dissection, though most medical schools continue to see experience with actual cadavers as preferable to entirely computer-based education.[27]

In the United States

Dissections of non-human animals have also been used for educational purposes, often in general science education where the use of human cadavers would not be justified. In the United States, dissection of frogs became common in college biology classes from the 1920s, and gradually began to be introduced at earlier stages of education. By 1988 an estimated 75 to 80 percent of American high school biology students were participating in a frog dissection, with a trend towards introduction in elementary schools. The dissected frogs are most commonly from the Rana genus. Other popular animals for high-school dissection at the time of that survey were, among vertebrates, fetal pigs, perch, and cats; and among invertebrates, earthworms, grasshoppers, crayfish, and starfish.[28]

Controversy over dissection in U.S. high schools became prominent in 1987, when a California student, Jenifer Graham, sued to require her school to let her complete an alternate project. The court ruled that mandatory dissections were permissible, but that Graham could ask to dissect a frog that had died of natural causes rather than one that was killed for the purposes of dissection; the practical impossibility of procuring a frog that had died of natural causes in effect let Graham opt out of the required dissection. The suit also gave considerable publicity to anti-dissection advocates. Graham appeared in a 1987 Apple Computer commercial for the virtual-dissection software Operation Frog.[29][30] The state of California passed a Student's Rights Bill in 1988 requiring that objecting students be allowed to complete alternative projects.[31] The trend towards students opting out of dissection increased through the 1990s.[32]

There are moves to gives students an alternate option to animal dissection[33]

In the United States, 17 states along with Washington, D.C., have enacted dissection-choice laws or policies that allow students in grades K-12 to opt-out of dissection and require teachers to provide non-animal assignments. California, Connecticut, D.C., Florida, Illinois, Louisiana, Maine, Massachusetts, Michigan, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia all have statewide laws or department of education policies that allow students to opt out of animal dissection in favor of a non-animal method. In addition, other states—including Arizona, Hawaii, Minnesota, Texas, and Utah—have more general policies on allowing students to opt out of material that they find objectionable on moral, religious, or ethical grounds. Many school districts, universities, and secondary schools have similar policies in place.[34]

Dissection alternatives

Concern for animal welfare is often at the root of most students’ objections to animal dissection.[35] Studies show that some students reluctantly participate in animal dissection out of fear of real or perceived punishment or ostracism from their teachers and peers, and many do not speak up about their ethical objections.[36] [37]

Proponents of animal-free teaching methodologies argue that alternatives to animal dissection can benefit educators by increasing teaching efficiency and lowering instruction costs while affording teachers an enhanced potential for the customization and repeat-ability of teaching exercises. Those in favor of dissection alternatives point to studies which have shown that computer-based teaching methods “saved academic and nonacademic staff time … were considered to be less expensive and an effective and enjoyable mode of student learning [and] … contributed to a significant reduction in animal use” because there is no set-up or clean-up time, no obligatory safety lessons, and no monitoring of misbehavior with animal cadavers, scissors, and scalpels. [38] [39] [40]

With software and other non-animal methods, there is also no expensive disposal of equipment or hazardous material removal. Some programs also allow educators to customize lessons and include built-in test and quiz modules that can track student performance. Furthermore, animals (whether dead or alive) can be used only once, while non-animal resources can be used for many years—an added benefit that could result in significant cost savings for teachers, school districts, and state educational systems. [41]

Several peer-reviewed comparative studies examining information retention and performance of students who dissected animals and those who used an alternative instruction method have concluded that the educational outcomes of students who are taught basic and advanced biomedical concepts and skills using non-animal methods are equivalent or superior to those of their peers who use animal-based laboratories such as animal dissection. [42] [43]

Elsewhere it has been reported that students’ confidence and satisfaction increased as did their preparedness for laboratories and their information-retrieval and communication abilities. Three separate studies at universities across the United States found that students who modeled body systems out of clay were significantly better at identifying the constituent parts of human anatomy than their classmates who performed animal dissection. [44] [45] [46]

Another study found that students preferred using clay modeling over animal dissection and performed just as well as their cohorts who dissected animals. [47]

In 2008, the National Association of Biology Teachers (NABT) affirmed their organization’s support for classroom animal dissection stating that they, “Encourage the presence of live animals in the classroom with appropriate consideration to the age and maturity level of the students …NABT urges teachers to be aware that alternatives to dissection have their limitations. NABT supports the use of these materials as adjuncts to the educational process but not as exclusive replacements for the use of actual organisms.” [48]

Additionally, the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) “supports including live animals as part of instruction in the K-12 science classroom because observing and working with animals firsthand can spark students' interest in science as well as a general respect for life while reinforcing key concepts” of biological sciences. NSTA also supports offering dissection alternatives to students who object to the practice. [49]

Databases with information on dissection alternatives

The NORINA database lists over 3,000 products which may be used as alternatives or supplements to animal use in education and training.[50] These include alternatives to dissection in schools. InterNICHE has a similar database and a loans system.[51]

Tools used

The following are tools commonly used in biological dissection.

- Scalpel

- Scissors (dissecting scissors)

- Thumb forceps or fine point splinter

- Mall probe and seeker

- Surgical spatula

- Magnifying glass

- Surgical chain and hooks

- Razor

- Surgical blow pipe

- Surgical prong

- Teasing needles

- Pipette or medicine dropper

- Ruler or caliper

- T-pins

- Dissecting pan

Additional images

-

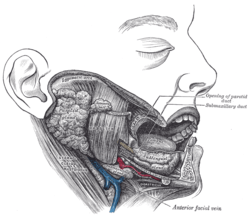

Dissection of a human cheek from Gray's Anatomy (1918).

-

.jpg)

Dissection of a spiny dogfish

-

Dissection of human axilla (armpit).

-

Human abdomen and thorax section prepared for a medical class.

-

Cow brain prepared for dissection, 2010 as part of Psychology class, Universidad del Valle de Mexico

-

GCSE dissection at Ruthin School

-

Dissection of the paw of a bengal tiger at the Art Academy of Cincinnati

References

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary - dissect". Douglas Harper. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary - Anatomize". Douglas Harper. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary - Anatomy". Douglas Harper. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ↑ J.A. Prahlow, R.W. Byard (2012). Atlas of Forensic Pathology. Springer Science+Business Media. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-61779-058-4.

- ↑ "Etymology Online Dictionary - Vivisection". Douglas Harper. Retrieved December 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Vivisection", Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2009: "Vivisection: operation on a living animal for experimental rather than healing purposes; more broadly, all experimentation on live animals."

- ↑ Von Staden, H. (1992). "The discovery of the body: Human dissection and its cultural contexts in ancient Greece". The Yale journal of biology and medicine 65 (3): 223–241. PMC 2589595. PMID 1285450.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 P Prioreschi, Determinants of the revival of dissection of the human body in the Middle Ages', Medical Hypotheses (2001) 56(2), 229–234)

- ↑ "Tragically, the prohibition of human dissection by Rome in 150 BC arrested this progress and few of their findings survived." Arthur Aufderheide, The Scientific Study of Mummies (2003), p. 5

- ↑ Vivian Nutton, 'The Unknown Galen', (2002), p. 89

- ↑ Heinrich Von Staden, Herophilus (1989), p. 140

- ↑ Philip Lutgendorf, Hanuman's Tale: The Messages of a Divine Monkey (2007), p. 348

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Savage-Smith, Emilie (1995). "Attitudes toward dissection in medieval Islam". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 50 (1): 67–110. doi:10.1093/jhmas/50.1.67. PMID 7876530.

- ↑ Islamic medicine, Hutchinson Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Emilie Savage-Smith (1996), "Medicine", in Roshdi Rashed, ed., Encyclopedia of the History of Arabic Science, Vol. 3, p. 903-962 [951-952]. Routledge, London and New York.

- ↑ Al-Dabbagh, S. A. (1978). "Ibn Al-Nafis and the pulmonary circulation". The Lancet 1: 1148.

- ↑ Reflections, Chairman's (2004). "Traditional Medicine Among Gulf Arabs, Part II: Blood-letting". Heart Views 5 (2): 74–85 [80].

- ↑ Huff, Toby (2011). Intellectual Curiosity and the Scientific Revolution: A Global Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 179. ISBN 978-1-107-00082-7.

- ↑ "In the 13th century, the realisation that human anatomy could only be taught by dissection of the human body resulted in its legalisation in several European countries between 1283 and 1365." Philip Cheung, Public Trust in Medical Research? (2007), p. 36.

- ↑ "Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious." Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), p. 195

- ↑ 'While during this period the Church did not forbid human dissections in general, certain edicts were directed at specific practices. These included the Ecclesia Abhorret a Sanguine in 1163 by the Council of Tours and Pope Boniface VIII's command to terminate the practice of dismemberment of slain crusaders' bodies and boiling the parts to enable defleshing for return of their bones. Such proclamations were commonly misunderstood as a ban on all dissection of either living persons or cadavers (Rogers & Waldron, 1986), and progress in anatomical knowledge by human dissection did not thrive in that intellectual climate', Arthur Aufderheide, The Scientific Study of Mummies (2003), p. 5

- ↑ 'It must be noted, however, that the pope did not forbid anatomical dissections but only the dissections performed with the purpose of preserving the bodies for distant burial', P. Prioreschi, Determinants of the revival of dissection of the human body in the Middle Ages', Medical Hypotheses (2001) 56(2), 229–234)

- ↑ 'Current scholarship reveals that Europeans had considerable knowledge of human anatomy, not just that based on Galen and his animal dissections. For the Europeans had performed significant numbers of human dissections, especially postmortem autopsies during this era', 'Many of the autopsies were conducted to determine whether or not the deceased had died of natural causes (disease) or whether there had been foul play, poisoning, or physical assault. Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious', Toby Huff, The Rise Of Modern Science (2003), p. 195

- ↑ See C. D. O'Malley Andreas Vesalius' Pilgrimage, Isis 45:2, 1954

- ↑ Freedman, David H. (September 2012). "20 Things you didn't know about autopsies". Discovery 9: 72.

- ↑ Cheung, pp. 37–44

- ↑ Cheung, pp. 33, 35

- ↑ F. Barbara Orlans, Tom L. Beauchamp, Rebecca Dresser, David B. Morton, and John P. Gluck (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. p. 213. ISBN 0-19-511908-8.

- ↑ Howard Rosenberg: Apple Computer's 'Frog' Ad Is Taken Off the Air. LA Times, November 10, 1987.

- ↑ F. Barbara Orlans, Tom L. Beauchamp, Rebecca Dresser, David B. Morton, and John P. Gluck (1998). The Human Use of Animals. Oxford University Press. p. 210. ISBN 0-19-511908-8.

- ↑ Orlans et al., pp. 209–211

- ↑ Johnson, Dirk (May 29, 1997). "Frogs' Best Friends: Students Who Won't Dissect Them". New York Times. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ http://www.freep.com/article/20140731/NEWS06/308010032/school-dissections-opt-out-PETA

- ↑ "Your Right Not to Dissect". PETA2.com. PETA2.

- ↑ Stainsstreet, M; Spofforth, N; Williams, T (1993). "Attitudes of undergraduat students to the uses of animals.". Studies in Higher Edcuation (18(2)): 177-196.

- ↑ Oakley, J (2012). "Dissection and choice in the science classroom: student experiences, teacher responses, and a critical analysis of the right to refuse.". Journal of Teaching and Learning (8(2)).

- ↑ Oakley, J (2013). ""I didn't feel right about animal dissection": Dissection objectors share their science class experiences.". Society & Animals (21(1)).

- ↑ Dewhurt, D; Jenkinson, L (1995). "The impact of computer-based alternatives on the use of animals in undergraduate teaching: A pilot study". ATLA (23(4)): 521-530.

- ↑ Predavec, M (2001). "Evaluation of E-Rat, a computer-based rat dissection, in terms of student learning outcomes.". Journal of Biological Education 35 (2): 75–80. doi:10.1080/00219266.2000.9655746.

- ↑ Youngblut, C (2001). "Use of multimedia technology to provide solutions to existing curriculum problems: Virtual frog dissection". Doctoral Dissertation.

- ↑ Dewhurt, D; Jenkinson, L (1995). "The impact of computer-based alternatives on the use of animals in undergraduate teaching: A pilot study". ATLA (23(4)): 521-530.

- ↑ Patronek, G.J.; Rauch, A (2007). "Systematic review of comparative studies examining alternatives to the harmful use of animals in biomedical education". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 230 (1): 37–43. doi:10.2460/javma.230.1.37.

- ↑ Knight, A (2007). "The effectiveness of humane teaching methods in veterinary education". ALTEX 24 (2): 91.

- ↑ Waters, J.R.; Van Meter, P; Perrotti, W; Drogo, S; Cyr, R.J (2005). "Cat dissection vs. sculpting human structures in clay: An analysis of two approaches to undergraduate human anatomy laboratory education". Advances in Physiology Education 29 (1): 27–34. doi:10.1152/advan.00033.2004.

- ↑ Motoike, H.K.; O'Kane, R.L.; Lenchner, E; Haspel, C (2009). "Clay modeling as a method to learn human muscles: A community college study". Anatomical Sciences Education 2 (1): 19–23. doi:10.1002/ase.61.

- ↑ Waters, J.R.; Van Meter, P; Perrotti, W; Drogo, S; Cyr, R.J. (2011). "Human clay models versus cat dissection: How the similarity between the classroom and the exam affects student performance". Advances in Physiology Education 35 (2): 227–236. doi:10.1152/advan.00030.2009.

- ↑ DeHoff, M.E.; Clark, K.L; Meganathan, K (2011). "Learning outcomes and student perceived value of clay modeling and cat dissection in undergraduate human anatomy and physiology.". Advances in Physiology Education 35 (1): 68–75. doi:10.1152/advan.00094.2010.

- ↑ "The Use of Animals in Biology Education". Position Statements: National Association of Biology Teachers. National Association of Biology Teachers. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ "NSTA Position Statement: Responsible Use of Live Animalsand Dissection in the Science Classroom". National Science Teachers Association. Retrieved 3 February 2015.

- ↑ NORINA

- ↑ InterNICHE

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dissection. |