Dipylidium caninum

| Cucumber tapeworm | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Platyhelminthes |

| Class: | Cestoda |

| Order: | Cyclophyllidea |

| Family: | Dipylidiidae |

| Genus: | Dipylidium |

| Species: | D. caninum |

| Binomial name | |

| Dipylidium caninum | |

Introduction

Dipylidium caninum, also called the flea tapeworm, double-pore tapeworm, or cucumber tapeworm (in reference to the shape of its cucumber-seed-like proglottids, though these also resemble grains of rice or sesame seeds), is a cyclophyllid cestode that infects organisms afflicted with fleas and canine chewing lice, including dogs, cats, and sometimes human pet-owners, especially children.

Adult Morphology

The adult worm is about 18 inches (46 cm) long. Gravid proglottids containing the worm's microscopic eggs are either passed in the definitive host's feces or may leave their host spontaneously and are then ingested by microscopic flea larvae (the intermediate hosts) in the surrounding environment. As in all members of family Dipylidiidae, proglottids of the adult worm have genital pores on both sides (hence the name double-pore tapeworm). Each side has a set of male and female reproductive organs. The uterus is paired with 16 to 20 radial branches each. The scolex has a retractable rostellum with four rows of hooks, along with the four suckers that all cyclophyllid cestodes have.

Life-Cycle

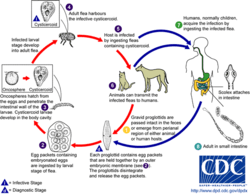

The definitive host within this life cycle is primarily canines, and occasionally felines, and in rare cases sometimes-young children. The intermediate hosts include fleas (Ctenocephalides spp.) and chewing lice. The first stage in the life cycle is when the gravid proglottids are either passed out through fecal matter, or actively crawl out of the anus of the host. The gravid proglottids once out of the definitive host release eggs. Then an intermediate host will ingest an egg, which develops into a cysticercoid larva. The adult flea or lice will then harbor the infective cysticercoid until a definitive host, such as a dog, becomes infected by ingesting an infected flea or lice while grooming themselves. Humans can also become infected by Dipylidium caninum by accidently ingesting an infected flea. In the small intestine of the definitive host the cysticercoid develops into an adult tapeworm, which reaches maturity approximately one month after infection. This adult tapeworm produces proglottids and over time the proglottids mature and become gravid and eventually detach from the tapeworm and the life cycle starts all over again.[1]

Pet Infections

Tapeworm infection usually does not cause pathology in the dog or cat, and most pets show no adverse reaction to infection other than increased appetite. The other tapeworm infecting cats is Taenia taeniaeformis, though this form is much less commonly encountered that the one currently under discussion here.

Human Infections

A human infection with Dipylidium caninum is rare, but if an infection does occur it is more likely to occur in young children. There have only been 16 reports of Dipylidium caninum infections in humans within the last 20 years, and almost all of the cases were found in children. Young children and toddlers are at a greater risk of infection because of how young children interact with their pets. A human may attain an infection by accidently ingesting an infected flea through food contamination or through the saliva of pets. Most infections are asymptomatic, but sometimes the following symptoms may be identified in an infected individual: mild diarrhea, abdominal colic, anorexia, restlessness, constipation, rectal itching and pain due to emerging proglottids through the anal cavity.[2]

Treatment & Prevention

As with most tapeworm infections, the drugs of choice are niclosamide or praziquantel. The best way to prevent human infection is to treat infected animals with products such as: FrontLine, which aid in killing the fleas on the animal.

Gallery

-

Dipylidium caninum egg packet

-

Dipylidium caninum proglottid

-

Dipylidium caninum

-

Dipylidium caninum worms

References

- ↑ "Dipylidium caninum Infection". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 24 April 2015.

- ↑ Garcia-Martos, Pedro; Garcia-Agudo, Lidia; Rodriguez-Iglesias, Manuel (26 May 2014). "Dipylidium caninum infection in an infant: a rare case report and literature review" (PDF). Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Biomedicine 4 (2): S565-S567. Retrieved 24 April 2015.