Dionysus

| Dionysus | |

|---|---|

| God of the Grape Harvest, Winemaking, Wine, Ritual Madness, Religious Ecstasy, and Theatre. | |

2nd-century Roman statue of Dionysus, after a Hellenistic model (ex-coll. Cardinal Richelieu, Louvre)[1] | |

| Abode | Mount Olympus |

| Symbol | Thyrsus, grapevine, leopard skin, panther, cheetah |

| Consort | Ariadne |

| Parents | Zeus and Semele |

| Siblings | Ares, Athena, Apollo, Artemis, Aphrodite, Hebe, Hermes, Heracles, Helen of Troy, Hephaestus, Perseus, Minos, the Muses, the Graces |

| Roman equivalent | Bacchus, Liber |

Dionysus (/daɪ.əˈnaɪsəs/; Greek: Διόνυσος, Dionysos) is the god of the grape harvest, winemaking and wine, of ritual madness, fertility,[2][3] theatre and religious ecstasy in Greek mythology. Alcohol, especially wine, played an important role in Greek culture with Dionysus being an important reason for this life style.[4] His name, thought to be a theonym in Linear B tablets as di-wo-nu-so (KH Gq 5 inscription),[5] shows that he may have been worshipped as early as c. 1500–1100 BC by Mycenean Greeks; other traces of the Dionysian-type cult have been found in ancient Minoan Crete.[6] His origins are uncertain, and his cults took many forms; some are described by ancient sources as Thracian, others as Greek.[7][8][9] In some cults, he arrives from the east, as an Asiatic foreigner; in others, from Ethiopia in the South. He is a god of epiphany, "the god that comes", and his "foreignness" as an arriving outsider-god may be inherent and essential to his cults. He is a major, popular figure of Greek mythology and religion, and is included in some lists of the twelve Olympians. Dionysus was the last god to be accepted into Mt. Olympus. He was the youngest and the only one to have a mortal mother.[10] His festivals were the driving force behind the development of Greek theatre. He is an example of a dying god.[11][12]

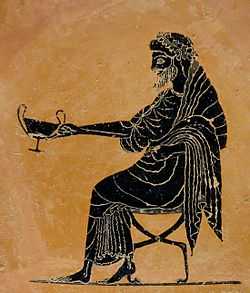

The earliest cult images of Dionysus show a mature male, bearded and robed. He holds a fennel staff, tipped with a pine-cone and known as a thyrsus. Later images show him as a beardless, sensuous, naked or half-naked androgynous youth: the literature describes him as womanly or "man-womanish".[13] In its fully developed form, his central cult imagery shows his triumphant, disorderly arrival or return, as if from some place beyond the borders of the known and civilized. His procession (thiasus) is made up of wild female followers (maenads) and bearded satyrs with erect penises. Some are armed with the thyrsus, some dance or play music. The god himself is drawn in a chariot, usually by exotic beasts such as lions or tigers, and is sometimes attended by a bearded, drunken Silenus. This procession is presumed to be the cult model for the human followers of his Dionysian Mysteries. In his Thracian mysteries, he wears the bassaris or fox-skin, symbolizing a new life. Dionysus is represented by city religions as the protector of those who do not belong to conventional society and thus symbolizes everything which is chaotic, dangerous and unexpected, everything which escapes human reason and which can only be attributed to the unforeseeable action of the gods.[14]

Also known as Bacchus (/ˈbækəs/ or /ˈbɑːkəs/; Greek: Βάκχος, Bakkhos), the name adopted by the Romans[15] and the frenzy he induces, bakkheia. His thyrsus is sometimes wound with ivy and dripping with honey. It is a beneficent wand but also a weapon, and can be used to destroy those who oppose his cult and the freedoms he represents. He is also called Eleutherios ("the liberator"), whose wine, music and ecstatic dance frees his followers from self-conscious fear and care, and subverts the oppressive restraints of the powerful. Those who partake of his mysteries are possessed and empowered by the god himself.[16] His cult is also a "cult of the souls"; his maenads feed the dead through blood-offerings, and he acts as a divine communicant between the living and the dead.[17]

In Greek mythology, he is presented as a son of Zeus and the mortal Semele, thus semi-divine or heroic: and as son of Zeus and Persephone or Demeter, thus both fully divine, part-chthonic and possibly identical with Iacchus of the Eleusinian Mysteries. Some scholars believe that Dionysus is a syncretism of a local Greek nature deity and a more powerful god from Thrace or Phrygia such as Sabazios[18] or Zalmoxis.[19]

Names

Etymology

The dio- element has been associated since antiquity with Zeus (genitive Dios). The earliest attested form of the name is Mycenaean Greek 𐀇𐀺𐀝𐀰, di-wo-nu-so, written in Linear B syllabic script, presumably for /Diwo(h)nūsoio/. This is attested on two tablets that had been found at Mycenaean Pylos and dated to the 12th or 13th century BC, but at the time, there could be no certainty on whether this was indeed a theonym.[20][21] But the 1989–90 Greek-Swedish Excavations at Kastelli Hill, Chania, unearthed, inter alia, four artefacts bearing Linear B inscriptions; among them, the inscription on item KH Gq 5 is thought to confirm Dionysus's early worship.[5]

Later variants include Dionūsos and Diōnūsos in Boeotia; Dien(n)ūsos in Thessaly; Deonūsos and Deunūsos in Ionia; and Dinnūsos in Aeolia, besides other variants. A Dio- prefix is found in other names, such as that of the Dioscures, and may derive from Dios, the genitive of the name of Zeus.[22]

The second element -nūsos is associated with Mount Nysa, the birthplace of the god in Greek mythology, where he was nursed by nymphs (the Nysiads),[23] but according to Pherecydes of Syros, nũsa was an archaic word for "tree".[24]

R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin of the name.[25]

The cult of Dionysus was closely associated with trees, specifically the fig tree, and some of his bynames exhibit this, such as Endendros "he in the tree" or Dendritēs, "he of the tree". Peters suggests the original meaning as "he who runs among the trees", or that of a "runner in the woods". Janda (2010) accepts the etymology but proposes the more cosmological interpretation of "he who impels the (world-)tree". This interpretation explains how Nysa could have been re-interpreted from a meaning of "tree" to the name of a mountain: the axis mundi of Indo-European mythology is represented both as a world-tree and as a world-mountain.[26]

Epithets

Dionysus was variably known with the following epithets:

Acratophorus, ("giver of unmixed wine"), at Phigaleia in Arcadia.[27]

Adoneus ("ruler") in his Latinised, Bacchic cult.[29]

Aegobolus ("goat killer") at Potniae, in Boeotia.[30]

Aesymnetes ("ruler" or "lord") at Aroë and Patrae in Achaea.

Agrios ("wild"), in Macedonia.

Briseus ("he who prevails") in Smyrna.[31][32]

Bromios ("Roaring" as of the wind, primarily relating to the central death/resurrection element of the myth,[33] but also to the god's famous transformations into lion and bull.[34] Also refers to the "boisterousness" of those who imbibe spirits, and is cognate with the "roar of thunder", although this aspect is corollary in that it is a reference to the god's parentage, not his innate qualities.)

Chthonios ("the subterranean")[35]

Dendrites ("he of the trees"), as a fertility god.

Dithyrambos, form of address used at his festivals, referring to his premature birth.

Eleutherios ("the liberator"), an epithet for both Dionysus and Eros.

Endendros ("he in the tree").[36]

Enorches ("with balls,"[37] with reference to his fertility, or "in the testicles" in reference to Zeus' sewing the baby Dionysus into his thigh, i.e., his testicles).[38] used in Samos and Lesbos.

Erikryptos ("completely hidden"), in Macedonia.

Euius (Euios), in Euripides' play, The Bacchae.

Iacchus, possibly an epithet of Dionysus and associated with the Eleusinian Mysteries. In Eleusis, he is known as a son of Zeus and Demeter. The name "Iacchus" may come from the Ιακχος (Iakchos), a hymn sung in honor of Dionysus.

Liknites ("he of the winnowing fan"), as a fertility god connected with the mystery religions. A winnowing fan was used to separate the chaff from the grain.

Lyaeus (Lyaios) ("he who unties") or releases from care and anxiety.

Melanaigis ("of the black goatskin") at the Apaturia festival.

Oeneus, as god of the wine press.

Pseudanor ("false man"), in Macedonia.

In the Greek pantheon, Dionysus (along with Zeus) absorbs the role of Sabazios, a Thracian/Phrygian deity. In the Roman pantheon, Sabazius became an alternative name for Bacchus.[39]

Mythology

Birth (and infant death and rebirth)

Dionysus had a strange birth that evokes the difficulty in fitting him into the Olympian pantheon. His mother was a mortal woman, Semele, the daughter of king Cadmus of Thebes, and his father was Zeus, the king of the gods. Zeus' wife, Hera, discovered the affair while Semele was pregnant. Appearing as an old crone (in other stories a nurse), Hera befriended Semele, who confided in her that Zeus was the actual father of the baby in her womb. Hera pretended not to believe her, and planted seeds of doubt in Semele's mind. Curious, Semele demanded of Zeus that he reveal himself in all his glory as proof of his godhood.

Though Zeus begged her not to ask this, she persisted and he agreed. Therefore he came to her wreathed in bolts of lightning; mortals, however, could not look upon an undisguised god without dying, and she perished in the ensuing blaze. Zeus rescued the unborn Dionysus by sewing him into his thigh. A few months later, Dionysus was born on Mount Pramnos in the island of Ikaria, where Zeus went to release the now-fully-grown baby from his thigh. In this version, Dionysus is born by two "mothers" (Semele and Zeus) before his birth, hence the epithet dimētōr (of two mothers) associated with his being "twice-born".

In the Cretan version of the same story, which Diodorus Siculus follows,[41] Dionysus was the son of Zeus and Persephone, the queen of the Greek underworld. Diodorus' sources equivocally identified the mother as Demeter.[42] A jealous Hera again attempted to kill the child, this time by sending Titans to rip Dionysus to pieces after luring the baby with toys. It is said that he was mocked by the Titans who gave him a thyrsus (a fennel stalk) in place of his rightful sceptre.[43] Zeus turned the Titans into dust with his thunderbolts, but only after the Titans ate everything but the heart, which was saved, variously, by Athena, Rhea, or Demeter. Zeus used the heart to recreate him in his thigh, hence he was again "the twice-born". Other versions claim that Zeus recreated him in the womb of Semele, or gave Semele the heart to eat to impregnate her.

The rebirth in both versions of the story is the primary reason why Dionysus was worshipped in mystery religions, as his death and rebirth were events of mystical reverence. This narrative was apparently used in several Greek and Roman cults, and variants of it are found in Callimachus and Nonnus, who refer to this Dionysus with the title Zagreus, and also in several fragmentary poems attributed to Orpheus.

The myth of the dismemberment of Dionysus by the Titans, is alluded to by Plato in his Phaedo (69d) in which Socrates claims that the initiations of the Dionysian Mysteries are similar to those of the philosophic path. Late Neo-Platonists such as Damascius explore the implications of this at length.[44]

Infancy at Mount Nysa

According to the myth, Zeus gave the infant Dionysus to the care of Hermes. One version of the story is that Hermes took the boy to King Athamas and his wife Ino, Dionysus' aunt. Hermes bade the couple to raise the boy as a girl, to hide him from Hera's wrath.[45] Another version is that Dionysus was taken to the rain-nymphs of Nysa, who nourished his infancy and childhood, and for their care Zeus rewarded them by placing them as the Hyades among the stars (see Hyades star cluster). Other versions have Zeus giving him to Rhea, or to Persephone to raise in the Underworld, away from Hera. Alternatively, he was raised by Maro.

Dionysus in Greek mythology is a god of foreign origin, and while Mount Nysa is a mythological location, it is invariably set far away to the east or to the south. The Homeric hymn to Dionysus places it "far from Phoenicia, near to the Egyptian stream". Others placed it in Anatolia, or in Libya ("away in the west beside a great ocean"), in Ethiopia (Herodotus), or Arabia (Diodorus Siculus).

According to Herodotus:

As it is, the Greek story has it that no sooner was Dionysus born than Zeus sewed him up in his thigh and carried him away to Nysa in Ethiopia beyond Egypt; and as for Pan, the Greeks do not know what became of him after his birth. It is therefore plain to me that the Greeks learned the names of these two gods later than the names of all the others, and trace the birth of both to the time when they gained the knowledge.—Herodotus, Histories 2.146

The Bibliotheca seems to be following Pherecydes, who relates how the infant Dionysus, god of the grapevine, was nursed by the rain-nymphs, the Hyades at Nysa.

Childhood

When Dionysus grew up, he discovered the culture of the vine and the mode of extracting its precious juice; but Hera struck him with madness, and drove him forth a wanderer through various parts of the earth. In Phrygia the goddess Cybele, better known to the Greeks as Rhea, cured him and taught him her religious rites, and he set out on a progress through Asia teaching the people the cultivation of the vine. The most famous part of his wanderings is his expedition to India, which is said to have lasted several years. According to a legend, when Alexander the Great reached a city called Nysa near the Indus river, the locals said that their city was founded by Dionysus in the distant past and their city was dedicated to the god Dionysus.[46] Returning in triumph he undertook to introduce his worship into Greece, but was opposed by some princes who dreaded its introduction on account of the disorders and madness it brought with it (e.g. Pentheus or Lycurgus).

Dionysus was exceptionally attractive. One of the Homeric hymns recounts how, while disguised as a mortal sitting beside the seashore, a few sailors spotted him, believing he was a prince. They attempted to kidnap him and sail him far away to sell for ransom or into slavery. They tried to bind him with ropes, but no type of rope could hold him. Dionysus turned into a fierce lion and unleashed a bear on board, killing those he came into contact with. Those who jumped off the ship were mercifully turned into dolphins. The only survivor was the helmsman, Acoetes, who recognized the god and tried to stop his sailors from the start.[47]

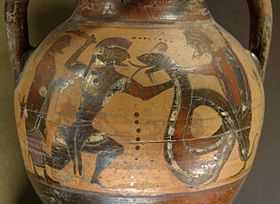

In a similar story, Dionysus desired to sail from Icaria to Naxos. He then hired a Tyrrhenian pirate ship. However, when the god was on board, they sailed not to Naxos but to Asia, intending to sell him as a slave. So Dionysus turned the mast and oars into snakes, and filled the vessel with ivy and the sound of flutes so that the sailors went mad and, leaping into the sea, were turned into dolphins.

Other stories

Midas

Dionysus discovered that his old school master and foster father, Silenus, had gone missing. The old man had been drinking, and had wandered away drunk, and was found by some peasants, who carried him to their king (alternatively, he passed out in Midas' rose garden). Midas recognized him, and treated him hospitably, entertaining him for ten days and nights with politeness, while Silenus entertained Midas and his friends with stories and songs. On the eleventh day, he brought Silenus back to Dionysus. Dionysus offered Midas his choice of whatever reward he wanted.

Midas asked that whatever he might touch should be changed into gold. Dionysus consented, though was sorry that he had not made a better choice. Midas rejoiced in his new power, which he hastened to put to the test. He touched and turned to gold an oak twig and a stone. Overjoyed, as soon as he got home, he ordered the servants to set a feast on the table. Then he found that his bread, meat, and wine turned to gold. Later, when his daughter embraced him, she too turned to gold.

Upset, Midas strove to divest himself of his power (the Midas Touch); he hated the gift he had coveted. He prayed to Dionysus, begging to be delivered from starvation. Dionysus heard and consented; he told Midas to wash in the river Pactolus. He did so, and when he touched the waters the power passed into them, and the river sands changed into gold. This was an etiological myth that explained why the sands of the Pactolus were rich in gold.

Pentheus

In the play, The Bacchae, written by Euripides, Dionysus returns to his birthplace, Thebes, which is ruled by his cousin Pentheus. Dionysus wants to exact revenge on Pentheus and the women of Thebes (his aunts Agave, Ino and Autonoe) for not believing his mother Semele's claims of being impregnated by Zeus, and for denying Dionysus's divinity (and therefore not worshiping him).

Dionysus slowly drives Pentheus mad, lures him to the woods of Mount Cithaeron, and then convinces him to spy/peek on the Maenads (female worshippers of Dionysus, who often experienced divine ecstasy). The Maenads are in an insane frenzy when Pentheus sees them (earlier in the play they had ripped apart a herd of cattle), and they catch him but mistake him for a wild animal. Pentheus is torn to shreds, and his mother (Agave, one of the Maenads), not recognizing her own son because of her madness, brutally tears his limbs off as he begs for his life.

As a result of their acts the women are banished from Thebes, ensuring Dionysus's revenge.

Lycurgus

When King Lycurgus of Thrace heard that Dionysus was in his kingdom, he imprisoned Dionysus' followers, the Maenads. Dionysus fled and took refuge with Thetis, and sent a drought which stirred the people into revolt. Dionysus then drove King Lycurgus insane and had him slice his own son into pieces with an axe in the belief that he was a patch of ivy, a plant holy to Dionysus. An oracle then claimed that the land would stay dry and barren as long as Lycurgus was alive. His people had him drawn and quartered. Following the death of the king, Dionysus lifted the curse. This story was told in Homer's epic, Iliad 6.136-7. In an alternative version, sometimes shown in art, Lycurgus tries to kill Ambrosia, a follower of Dionysus, who was transformed into a vine that twined around the enraged king and restrained him, eventually killing him.[48]

Prosymnus

A better-known story is that of his descent to Hades to rescue his mother Semele, whom he placed among the stars.[49] Dionysus feared for his mother, whom he had not seen since birth. He bypassed the god of death, known as Thanatos, thus successfully returning Semele to Mount Olympus. Out of the twelve Olympians, he was of the few that could restore the deceased from the underworld back to life.[50] He made the descent from a reputedly bottomless pool on the coast of the Argolid near the prehistoric site of Lerna. He was guided by Prosymnus or Polymnus, who requested, as his reward, to be Dionysus' lover. Prosymnus died before Dionysus could honor his pledge, so in order to satisfy Prosymnus' shade, Dionysus fashioned a phallus from an olive branch and sat on it at Prosymnus' tomb.[51] This story survives in full only in Christian sources whose aim was to discredit pagan mythology. It appears to have served as an explanation of the secret objects that were revealed in the Dionysian Mysteries.[52]

Ampelos

Another myth according to Nonnus involves Ampelos, a satyr, who was loved by Dionysus.[53] Foreseen by Dionysus, the youth was killed in an accident riding a bull maddened by the sting of an Ate's gadfly. The Fates granted Ampelos a second life as a vine, from which Dionysus squeezed the first wine.[54]

Chiron

Young Dionysus was also said to have been one of the many famous pupils of the centaur Chiron. According to Ptolemy Chennus in the Library of Photius, "Dionysius was loved by Chiron, from whom he learned chants and dances, the bacchic rites and initiations."[55]

Secondary myths

When Hephaestus bound Hera to a magical chair, Dionysus got him drunk and brought him back to Olympus after he passed out.

A third descent by Dionysus to Hades is invented by Aristophanes in his comedy The Frogs. Dionysus, as patron of the Athenian dramatic festival, the Dionysia, wants to bring back to life one of the great tragedians. After a competition Aeschylus is chosen in preference to Euripides.

When Theseus abandoned Ariadne sleeping on Naxos, Dionysus found and married her. She bore him a son named Oenopion, but he committed suicide or was killed by Perseus. In some variants, he had her crown put into the heavens as the constellation Corona; in others, he descended into Hades to restore her to the gods on Olympus. Another different account claims Dionysus ordered Theseus to abandon Ariadne on the island of Naxos for he had seen her as Theseus carried her onto the ship and had decided to marry her.

Psalacantha, a nymph, failed at winning the love of Dionysus as his main love interest at the moment was Ariadne, and ended up being changed into a plant.

Callirrhoe was a Calydonian woman who scorned Coresus, a priest of Dionysus, who threatened to afflict all the women of Calydon with insanity (see Maenad). The priest was ordered to sacrifice Callirhoe but he killed himself instead. Callirhoe threw herself into a well which was later named after her.

Consorts and children

| Greek Mythology |

|---|

|

| Deities |

|

|

| Heroes and heroism |

|

| Related |

|

| Greek mythology portal |

- Aphrodite

- Ariadne

- Nyx

- Althaea

- Deianeira

- Circe

- Aura

- Iacchus

- twin of Iacchus, killed by Aura instantly upon birth

- Nicaea

- Araethyrea or Chthonophyle (or again Ariadne)

- Physcoa

- Narcaeus

- Pallene

- Carya

- Percote

- Priapus (possibly)[56]

- Chione, Naiad nymph

- Priapus (possibly)[57]

- Alexirrhoe

- Alphesiboea

- Medus

- unnamed

- Thysa[58]

Genealogy of the Olympians in Greek mythology

Parallels with Christianity

The earliest discussions of mythological parallels between Dionysus and the figure of the Christ in Christian theology can be traced to Friedrich Hölderlin, whose identification of Dionysus with Christ is most explicit in Brod und Wein (1800–1801) and Der Einzige (1801–1803).[59]

Theories regarding such parallels were popular in the 19th century but were later on mostly rejected by contemporary scholarship. A few modern scholars such as Martin Hengel, Barry Powell, Robert M. Price, and Peter Wick, among others, argue that Dionysian religion and Christianity have notable parallels. They point to the symbolism of wine and the importance it held in the mythology surrounding both Dionysus and Jesus Christ;[60][61] though, Wick argues that the use of wine symbolism in the Gospel of John, including the story of the Marriage at Cana at which Jesus turns water into wine, was intended to show Jesus as superior to Dionysus.[62]

A few scholars of comparative mythology identify both Dionysus and Jesus with the dying-and-returning god mythological archetype.[12] However, this identification is often seen as superficial as most such deities had a cyclical nature, as they died and were reborn each year, representing the cycle of nature, while the resurrection of Christ was a single event placed in a specific historical and geographical context. On the other hand, Dionysus life-death-rebirth cycle was strongly tied to the grape harvest. Moreover it has been noted that the details of Dionysus death and rebirth are starkly different both in content and symbolism from Jesus, with Dionysus being (in the most common myth) torn to pieces and eaten by the titans and "eventually restored to a new life" from the heart that was left over.[63][64] Other elements, such as the celebration by a ritual meal of bread and wine, also have parallels.[65] Powell, in particular, argues precursors to the Catholic notion of transubstantiation can be found in Dionysian religion.[65] However such claims are strongly disputed as the rituals of Dionysus did not involve the transformation of the substance of bread and wine in the god himself. Rather the myth stated that Dionysus became the wine of libation, which was not drunk or consumed in any way, hence having a very different symbolism.

Another parallel can be seen in The Bacchae where Dionysus appears before King Pentheus on charges of claiming divinity which is compared to the New Testament scene of Jesus being interrogated by Pontius Pilate.[62][65][66] However several scholars dispute this parallel, since while Jesus, during the trial before Pilate, did not affirm openly he was a god nor asked for any honor, Dionysus was arrested by Pentheus after making the women of Thebes mad and complaining about the fact that the city of Thebes, and its king, have refused to honor him. Moreoever, the confrontation of Dionysus and Pentheus also ends with Pentheus dying, torn into pieces by the mad women, including his mother. The details of the story, including its resolution, make the Dionysus story radically different than the one of Jesus, except for the parallel of the arrest, which is a detail that appears in many biographies as well.[67]

Most modern biblical scholars and historians today, both conservative and liberal, reject most of the parallelomania between the cult of Dionysus and Christ, asserting that the similarities are superficial at best, most often vaguely general and universal parallels found in many stories, both historical and mythical, and that the symbolism represented by the similar themes are radically different.[64][68][69][70]

Symbolism

The bull, serpent, ivy, and wine are characteristic of Dionysian atmosphere. Dionysus is also strongly associated with satyrs, centaurs, and sileni. He is often shown riding a leopard, wearing a leopard skin, or in a chariot drawn by panthers, and may also be recognized by the thyrsus he carries. Besides the grapevine and its wild barren alter-ego, the toxic ivy plant, both sacred to him, the fig was also his symbol. The pinecone that tipped his thyrsus linked him to Cybele. Dionysus had two extreme natures to his personality. For instance, he could shift from bringing bliss and relaxation, which then often transitioned into bitterness and fury. Dionysus personified the nature of wine. When used reasonably it can be pleasant, however, if misused it can provoke negative effects.[71] The Dionysia and Lenaia festivals in Athens were dedicated to Dionysus. On numerous vases (referred to as Lenaia vases), the god is shown participating in the ritual sacrifice as a masked and clothed pillar (sometimes a pole, or tree is used), while his worshipers eat bread and drink wine. Initiates worshipped him in the Dionysian Mysteries, which were comparable to and linked with the Orphic Mysteries, and may have influenced Gnosticism. Orpheus was said to have invented the Mysteries of Dionysus.[72]

Dionysus was another god of resurrection and he was strongly linked to the bull. In a cult hymn from Olympia, at a festival for Hera, Dionysus is invited to come as a bull; "with bull-foot raging." Walter Burkert relates, "Quite frequently [Dionysus] is portrayed with bull horns, and in Kyzikos he has a tauromorphic image," and refers also to an archaic myth in which Dionysus is slaughtered as a bull calf and impiously eaten by the Titans.[12] In the Classical period of Greece, the bull and other animals identified with deities were separated from them as their agalma, a kind of heraldic show-piece that concretely signified their numinous presence.[12]

Bacchus and the Bacchanalia

A mystery cult to Bacchus was brought to Rome from the Greek culture of southern Italy or by way of Greek-influenced Etruria. It was established c.200 BC in the Aventine grove of Stimula by a priestess from Campania, near the temple where Liber Pater ("The Free Father") had a State-sanctioned, popular cult. Liber was a native Roman god of wine, fertility, and prophecy, patron of Rome's plebeians (citizen-commoners) and a close equivalent to Bacchus-Dionysus Eleutherios.

In Livy's account, the new Bacchic mysteries were originally restricted to women and held only three times a year; but were corrupted by the Etruscan-Greek version, and thereafter drunken men and women of all ages and social classes cavorted in a sexual free-for-all five times a month. Livy relates their various outrages against Rome's civil and religious laws and morality; a secretive, subversive and potentially revolutionary counter-culture. The cult was suppressed by the State with great ferocity; of the 7,000 arrested, most were executed. Modern scholarship treats much of Livy's account with skepticism; more certainly, a Senatorial edict, the Senatus consultum de Bacchanalibus was distributed throughout Roman and allied Italy. It banned the former Bacchic cult organisations. Each meeting must seek prior senatorial approval through a praetor. No more than three women and two men were allowed at any one meeting, Those who defied the edict risked the death penalty.

Bacchus was conscripted into the official Roman pantheon as an aspect of Liber, and his festival was inserted into the Liberalia. In Roman culture, Liber, Bacchus and Dionysus became virtually interchangeable equivalents. Bacchus was euhemerised as a wandering hero, conqueror and founder of cities. He was a patron deity and founding hero at Leptis Magna, birthplace of the emperor Septimius Severus, who promoted his cult. In some Roman sources, the ritual procession of Bacchus in a tiger-drawn chariot, surrounded by maenads, satyrs and drunks, commemorates the god's triumphant return from the conquest of India, the historical prototype for the Roman Triumph. Bacchus was attended by men and women accomplished in the arts of rural industry; wherever he came he taught husbandry and vine cultivation; being received everywhere with festivity and welcome. Lycurgus king of Thrace and Pentheus king of Thebes opposed importing the sciences of the east. To punish them Bacchus caused lycurgus to be torn to pieces by wild horses and spread delusion among the family of Pentheus so they thought him a wild boar and inflicted a thousand wounds.[74]

In art

Classical

The god appeared on many kraters and other wine vessels from classical Greece. His iconography became more complex in the Hellenistic period, between severe archaising or Neo Attic types such as the Dionysus Sardanapalus and types showing him as an indolent and androgynous young man and often shown nude (see the Dionysus and Eros, Naples Archeological Museum). The 4th-century Lycurgus Cup in the British Museum is a spectacular cage cup which changes colour when light comes through the glass; it shows the bound King Lycurgus being taunted by the god and attacked by a satyr.

Elizabeth Kessler has theorized that a mosaic appearing on the triclinium floor of the House of Aion in Nea Paphos, Cyprus, details a monotheistic worship of Dionysus.[75] In the mosaic, other gods appear but may only be lesser representations of the centrally imposed Dionysus.

Modern views

The Renaissance not only played a huge role in art but the movement revived the Roman and Greek ideals and themes in visual art of Bacchus. Bacchus, who once represented resurrection in Christianity, was himself resurrected. Bacchus once again became a proper subject for artist. The hand of Michelangelo, which was employed by Cardinal Raffaele Riario to produce a statue of him in his palace during the Renaissance, completed the rehabilitation of the ancient god of wine.[76]

Dionysus has remained an inspiration to artists, philosophers and writers into the modern era. In The Birth of Tragedy (1872), the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche contrasted Dionysus with the god Apollo as a symbol of the fundamental, unrestrained aesthetic principle of force, music, and intoxication versus the principle of form, beauty, and sight represented by the latter. Nietzsche also claimed that the oldest forms of Greek Tragedy were entirely based on suffering of Dionysus. Nietzsche continued to contemplate the character of Dionysus, which he revisited in the final pages of his 1886 work Beyond Good and Evil. This reconceived Nietzschean Dionysus was invoked as an embodiment of the central will to power concept in Nietzsche's later works The Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist and Ecce Homo.

Károly Kerényi, a scholar in classical philology and one of the founders of modern studies in Greek mythology characterized Dionysus as representative of the psychological life force (Zoê).[77] Other scholars proposing psychological interpretations have placed Dionysus' emotionality in the foreground by focusing on the joy, terror or hysteria associated with the god.[78][79][80][81][82]

The Russian poet and philosopher Vyacheslav Ivanov elaborated the theory of Dionysianism, which traces the roots of literary art in general and the art of tragedy in particular to ancient Dionysian mysteries. His views were expressed in the treatises The Hellenic Religion of the Suffering God (1904), and Dionysus and Early Dionysianism (1921).

Inspired by James Frazer, some have labeled Dionysus a life-death-rebirth deity. The mythographer Karl Kerenyi devoted much energy to Dionysus over his long career; he summed up his thoughts in Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Bollingen, Princeton, 1976).

.jpg)

by John Reinhard Weguelin

Dionysus is the main character of Aristophanes' play The Frogs, later updated to a modern version by Burt Shevelove (libretto) and Stephen Sondheim (music and lyrics) ("The time is the present. The place is ancient Greece. ... "). In the play, Dionysus and his slave Xanthius venture to Hades to bring a famed writer back from the dead, with the hopes that the writer's presence in the world will fix all nature of earthly problems. In Aristophanes' play, Euripides competes against Aeschylus to be recovered from the underworld; In Sondheim and Shevelove's, George Bernard Shaw faces William Shakespeare.

Dionysus is one of the central myths explored in the 2011 Weaponized anthology The Immanence of Myth.[83]

Walt Disney has depicted the character on a number of occasions. The first such portrayal of Silenus or Dionysus as the Roman Bacchus, was in the "Pastoral" segment of Walt Disney's third classic Fantasia. In keeping with the more fun-loving Roman god, he is portrayed as an overweight, happily drunk man wearing a tunic and cloak, grape leaves on his head, carrying a goblet of wine, and riding a drunken donkey named Jacchus ("jackass"). He is friends with the fauns and centaurs, and is shown celebrating a harvest festival. He was depicted as an overweight drunkard as opposed to his youthful descriptions in myths. He has bright pink skin and rosy red cheeks hinting at his drunkenness. He always carries either a bottle or glass of wine in his hand, and like in the myths, wears a wreath of grape leaves upon his head.

In music Dionysius (together with Demeter) was used as an archetype for the character Tori by contemporary artist Tori Amos in her 2007 album American Doll Posse, and the Canadian rock band Rush refer to a confrontation and hatred between Dionysus and Apollo in the Cygnus X-1 duology.

Versions of Dionysius has also appeared in modern fiction. The Romanised equivalent of Dionysus was referenced in the 1852 plantation literature novel Aunt Phillis's Cabin, which featured a character named Uncle Bacchus, who was so-named due to his excessive alcoholism. Comics writers Eddie Campbell and Grant Morrison have both utilised the character. Morrison claims that the myth of Dionysus provides the inspiration for his violent and explicit graphic novel Kill Your Boyfriend, whilst Campbell used the character in his Deadface series to explore both the conventions of super-hero comic books and artistic endeavour. Dionysus along with Lilith are central characters in James Curcio's 2011 novel Fallen Nation: Party At The World's End. A version of Bacchus appears in C. S. Lewis' Prince Caspian, part of The Chronicles of Narnia.

Lewis depicts him as dangerous-looking, androgynous young boy who helps Aslan awaken the spirits of the Narnian trees and rivers. He does not appear in the 2008 film version. Rick Riordan's series of books Percy Jackson & The Olympians presents Dionysus as an uncaring, childish and spoiled god who, as a punishment for chasing a nymph, has to work in Camp Half-Blood and stay off alcohol (The film adaptation Percy Jackson: Sea of Monsters expands on this in that Dionysus can pour himself wine, but it automatically turns into water in his glass).

In Fred Saberhagen's 2001 novel, God of the Golden Fleece, a young man in a post-apocalyptic world picks up an ancient piece of technology shaped in the likeness of the Dionysus. Here, Dionysus is depicted as a relatively weak god, albeit a subversive one whose powers are able to undermine the authority of tyrants.

In 2009 the poet Stephen Howarth and veteran theatre producer Andrew Hobbs collaborated on a play entitled Bacchus in Rehab with Dionysus as the central character. The authors describe the piece as "combining highbrow concept and lowbrow humour."[84]

The second season of the TV series True Blood involves a plot line wherein a maenad, Maryann, causes mayhem in the Louisiana town of Bon Temps in attempt to summon Dionysus.

Dionysus, going by his Roman name "Bacchus," is a character in the 2011 video game Rock of Ages. Bacchus is a playable character in the multiplayer online battle arena Smite. He is a melee tank and is nicknamed "God of Wine".[85]

Names originating from Dionysus

- Dion (also spelled Deion, Deon and Dionne)

- Denise (also spelled Denice, Daniesa, Denese, and Denisse)

- Dennis, Denis or Denys (including the derivative surnames Denison and Dennison), Denny, Dennie

- Denis (Croatian), Dionis, Dionisie (Romanian)

- Dénes (Hungarian)

- Dionisio/Dyonisio (Spanish), Dionigi (Italian)

- Διονύσιος, Διονύσης, Νιόνιος (Dionysios, Dionysis, Nionios Modern Greek)

- Deniska (diminutive of Russian Denis, itself a derivative of the Greek)

- Dionísio (Portuguese)

- Dionizy (Polish)

- Deniz (Turkish)

Gallery

-

The Ludovisi Dionysus with panther, satyr and grapes on a vine (Palazzo Altemps, Rome)

-

Statue of Dionysus (Sardanapalus) (Museo Palazzo Massimo Alle Terme, Rome)

-

Dionysus extending a drinking cup (kantharos), late 6th century BC

-

Drinking Bacchus (1623) Guido Reni

-

thumb|Statue of Dionysus in Remich Luxembourg

See also

- Apollonian and Dionysian

- Ascolia

- Bacchanalia

- Bacchic art

- Dionysian Mysteries

- Orgia

- Theatre of Dionysus

Notes

- ↑ Another variant, from the Spanish royal collection, is at the Museo del Prado, Madrid: illustration.

- ↑ Hedreen, Guy Michael. Silens in Attic Black-figure Vase-painting: Myth and Performance. University of Michigan Press. 1992. ISBN 9780472102952. page 1

- ↑ James, Edwin Oliver. The Tree of Life: An Archaeological Study. Brill Publications. 1966. page 234. ISBN 9789004016125

- ↑ Gately, Iain (2008). Drink. Gotham Books. p. 11. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Raymoure, K.A. (November 2, 2012). "Khania Linear B Transliterations". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "Possible evidence of human sacrifice at Minoan Chania". Archaeology News Network. 2014. Raymoure, K.A. "Khania KH Gq Linear B Series". Minoan Linear A & Mycenaean Linear B. Deaditerranean. "KH 5 Gq (1)". DĀMOS: Database of Mycenaean at Oslo. University of Oslo.

- ↑ Kerenyi 1976.

- ↑ Thomas McEvilley, The Shape of Ancient Thought, Allsworth press, 2002, pp. 118–121. Google Books preview

- ↑ Reginald Pepys Winnington-Ingram, Sophocles: an interpretation, Cambridge University Press, 1980, p.109 Google Books preview

- ↑ Zofia H. Archibald, in Gocha R. Tsetskhladze (Ed.) Ancient Greeks west and east, Brill, 1999, p.429 ff.Google Books preview

- ↑ Sacks, David; Murray, Oswyn; Brody, Lisa R. (2009-01-01). Encyclopedia of the Ancient Greek World. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438110202. Retrieved 20 April 2013.

- ↑ Dionysus, greekmythology.com

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Burkert, Walter, Greek Religion, 1985 pp. 64, 132

- ↑ Otto, Walter F. (1995). Dionysus Myth and Cult. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-20891-2.

- ↑ Gods of Love and Ecstasy, Alain Danielou p.15

- ↑ In Greek "both votary and god are called Bacchus". Burkert, Greek Religion 1985:162. For the initiate as Bacchus, see Euripides, Bacchantes 491. For the god, who alone is Dionysus, see Sophocles, Oedipus the King 211 and Euripides, Hippolytus 560.

- ↑ Sutton, p.2, mentions Dionysus as The Liberator in relation to the city Dionysia festivals. In Euripides, Bacchae 379–385: "He holds this office, to join in dances, [380] to laugh with the flute, and to bring an end to cares, whenever the delight of the grape comes at the feasts of the gods, and in ivy-bearing banquets the goblet sheds sleep over men."

- ↑ Xavier Riu, Dionysism and Comedy, Rowman and Littlefield, 1999, p.105

- ↑ Dictionary of Ancient Deities by Patricia Turner and the late Charles Russell Coulter, 2001, p.152.

- ↑ Dictionary of Ancient Deities by Patricia Turner and the late Charles Russell Coulter, 2001, p.520.

- ↑ John Chadwick, The Mycenaean World, Cambridge University Press, 1976, 99ff: "But Dionysos surprisingly appears twice at Pylos, in the form Diwonusos, both times irritatingly enough on fragments, so that we have no means of verifying his divinity."

- ↑ "The Linear B word di-wo-nu-so". Palaeolexicon. Word study tool of ancient languages.

- ↑ This is the view of Garcia Ramon (1987) and Peters (1989), summarised and endorsed in Janda (2010:20).

- ↑ Fox, p. 217, "The word Dionysos is divisible into two parts, the first originally Διος (cf. Ζευς), while the second is of an unknown signification, although perhaps connected with the name of the Mount Nysa which figures in the story of Lykourgos: (...) when Dionysos had been reborn from the thigh of Zeus, Hermes entrusted him to the nymphs of Mount Nysa, who fed him on the food of the gods, and made him immortal."

- ↑ Testimonia of Pherecydes in an early 5th-century BC fragment, FGrH 3, 178, in the context of a discussion on the name of Dionysus: "Nũsas (acc. pl.), he [Pherecydes] said, was what they called the trees."

- ↑ R. S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 337.

- ↑ see Janda (2010), 16-44 for a detailed account.

- ↑ Pausanias, 8.39.6.

- ↑ Stephanus of Byzantium, s.v. Ακρωρεία

- ↑ Ausonius, Epigr. xxix. 6.

- ↑ Pausanias, ix. 8. § 1.

- ↑ Aristid.Or.41

- ↑ Macr.Sat.I.18.9

- ↑ For a parallel see pneuma/psuche/anima The core meaning is wind as "breath/spirit"

- ↑ Bulls in antiquity were said to roar.

- ↑ Kerenyi, C. (1967). Eleusis: Archetypal Image of Mother and Daughter. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-01915-0; Kerenyi 1976). Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life. Princeton University Press.

- ↑ Janda (2010), 16-44.

- ↑ Kerenyi 1976:286.

- ↑ Jameson 1993, 53. Cf.n16 for suggestions of Devereux on "Enorkhes,"

- ↑ Rosemarie Taylor-Perry, The God Who Comes: Dionysian Mysteries Revisited. Algora Press 2003, p.89, cf. Sabazius.

- ↑ "Sarcophagus Depicting the Birth of Dionysus". The Walters Art Museum.

- ↑ Diorodus V 75.4, noted by Karl Kerényi, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton University Press) 1976, "The Cretan core of the Dionysos myth" p 110 note 213 and pp 110-114.

- ↑ Diodorus III 64.1, also noted by Kerény (110 note 214.)

- ↑ Damascius, Commentary on the Phaedo, I, 170, see in translation Westerink, The Greek Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo, vol. II (The Prometheus Trust, Westbury) 2009

- ↑ Damascius, Commentary on the Phaedo, I, 1-13 and 165-172, see in translation Westerink, The Greek Commentaries on Plato's Phaedo, vol. II, The Prometheus Trust, Westbury, 2009

- ↑ Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Includes Frazer's notes. ISBN 0-674-99135-4, ISBN 0-674-99136-2

- ↑ Arrian, Anabasis, 5.1.1-2.2

- ↑ "Theoi.com" Homeric Hymn to Dionysus". Theoi.com. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

- ↑ "British Museum - The Lycurgus Cup". britishmuseum.org.

- ↑ Hyginus, Astronomy 2.5.

- ↑ "Dionysus-the Collected Myths,", Carnaval Travel Presents: Roots of Greco-Roman Bacchanalia website, 2005. Retrieved on 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Clement of Alexandria, Protreptikos, II-30 3-5

- ↑ Arnobius, Against the Gentiles 5.28 (Dalby 2005, pp. 108–117)

- ↑ Ovid, Fasti 3. 407 ff (trans.Boyle) (Roman poetry 1st century BC to 1st century AD): "[The constellation] Grape-Gatherer (Vindemitor) . . . Its cause, too, takes a moment to teach. Beardless Ampelos, they say, a Nympha’s and a Satyrus’s son, was loved by Bacchus [Dionysos] on Ismarian hills [in Thrake]. quoted at theoi.com

- ↑ Nonnus, Dionysiaca (X.175-430; XI; XII.1-117); (Dalby 2005, pp. 55–62).

- ↑ Photius, Library; "Ptolemy Chennus, New History"

- ↑ Hesychius of Alexandria s. v. Priēpidos

- ↑ Scholia on Theocritus, Idyll 1. 21

- ↑ Strabo, Geography, 10.3.13, quotes the non-extant play Palamedes which seems to refer to Thysa, a daughter of Dionysus, and her (?) mother as participants of the Bacchic rites on Mount Ida, but the quoted passage is corrupt.

- ↑ The mid-19th-century debates are traced in G.S. Williamson, The Longing for Myth in Germany, 2004.

- ↑ Pausanias, Description of Greece 6. 26. 1 - 2

- ↑ Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 2. 34a

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Wick, Peter (2004). "Jesus gegen Dionysos? Ein Beitrag zur Kontextualisierung des Johannesevangeliums". Biblica (Rome: Pontifical Biblical Institute) 85 (2): 179–198. Retrieved 2007-10-10.

- ↑ Detienne, Marcel. Dionysus Slain. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1979.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Evans, Arthur. The God of Ecstasy. New York: St. Martins' Press, 1989

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 Powell, Barry B., Classical Myth Second ed. With new translations of ancient texts by Herbert M. Howe. Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1998.

- ↑ Studies in Early Christology, by Martin Hengel, 2005, p.331 (ISBN 0567042804)

- ↑ Dalby, Andrew (2005). The Story of Bacchus. London: British Museum Press.

- ↑ Heinrichs, Albert. "He Has a God in Him": Human and Divine in the Modern Perception of Dionysus."

- ↑ Sandmel, S (1962). "Parallelomania". Journal of Biblical Literature 81 (1): 1–13.

- ↑ Gerald O'Collins, "The Hidden Story of Jesus" New Blackfriars Volume 89, Issue 1024, pages 710–714, November 2008

- ↑ Nick Pontikis. "Myth Man's Dionysus Homework Help," Thanasis Olympic Greek website,1999. Retrieved on 11 November 2012.

- ↑ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca Library and Epitome, 1.3.2. "Orpheus also invented the mysteries of Dionysus, and having been torn in pieces by the Maenads he is buried in Pieria."

- ↑ "British Museum - statue". British Museum.

- ↑ William Godwin (1876). "Lives of the Necromancers". p. 36.

- ↑ Kessler, E., Dionysian Monotheism in Nea Paphos, Cyprus,

- ↑ Gately, Iain (2008). Drink (1 ed.). Gotham Books. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-592-40464-3.

- ↑ Kerenyi, K., Dionysus: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life (Princeton/Bollingen, 1976).

- ↑ Jeanmaire, H. Dionysus: histoire du culte de Bacchus, (p.106ff) Payot, (1951)

- ↑ Johnson, R. A. 'Ecstasy; Understanding the Psychology of Joy' HarperColling (1987)

- ↑ Hillman, J. 'Dionysus Reimagined' in The Myth of Analysis (pp.271-281) HarperCollins (1972); Hillman, J. 'Dionysus in Jung's Writings' in Facing The Gods, Spring Publications (1980)

- ↑ Thompson, J. 'Emotional Intelligence/Imaginal Intelligence' in Mythopoetry Scholar Journal, Vol 1, 2010

- ↑ Lopez-Pedraza, R. 'Dionysus in Exile: On the Repression of the Body and Emotion', Chiron Publications (2000)

- ↑ "The Immanence of Myth". weaponized.net.

- ↑ Facsimile Productions - Current Productions

- ↑ "Bacchus". Smite Wiki. Retrieved 2014-06-29.

References

- Dalby, Andrew (2005). The Story of Bacchus. London: British Museum Press. ISBN 0-7141-2255-6.

- Farnell, Lewis Richard, The Cults of the Greek States, 1896. Volume V, cf. Chapter IV, Cults of Dionysos; Chapter V, Dionysiac Ritual; Chapter VI, Cult-Monuments of Dionysos; Chapter VII, Ideal Dionysiac Types.

- Fox, William Sherwood, The Mythology of All Races, v.1, Greek and Roman, 1916, General editor, Louis Herbert Gray.

- Janda, Michael, Die Musik nach dem Chaos, Innsbruck 2010.

- Jameson, Michael. "The Asexuality of Dionysus." Masks of Dionysus. Ed. Thomas H. Carpenter and Christopher A. Faraone. Ithaca: Cornell UP, 1993. ISBN 0-8014-8062-0. 44-64.

- Kerényi, Karl, Dionysos: Archetypal Image of Indestructible Life, (Princeton: Bollingen) 1976.

- Pickard-Cambridge, Arthur, The Theatre of Dionysus at Athens, 1946.

- Powell, Barry B., Classical Myth, 5th edition, 2007.

- Ridgeway, William, Origin of Tragedy, 1910. Kessinger Publishing (June 2003). ISBN 0-7661-6221-4.

- Ridgeway, William, The Dramas and Dramatic Dances of non-European Races in special reference to the origin of Greek Tragedy, with an appendix on the origin of Greek Comedy, 1915.

- Riu, Xavier, Dionysism and Comedy, Rowman and Littlefield Publishers (1999). ISBN 0-8476-9442-9.

- Seaford, Richard. "Dionysos", Routledge (2006). ISBN 0-415-32488-2.

- Smith, William, Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, 1870, article on Dionysus

- Sutton, Dana F., Ancient Comedy, Twayne Publishers (August 1993). ISBN 0-8057-0957-6.

Further reading

- Livy, History of Rome, Book 39:13, Description of banned Bacchanalia in Rome and Italy

- Detienne, Marcel, Dionysos at Large, tr. by Arthur Goldhammer, Harvard University Press, 1989. ISBN 0-674-20773-4. (Originally in French as Dionysos à ciel ouvert, 1986)

- Albert Henrichs, Between City and Country: Cultic Dimensions of Dionysus in Athens and Attica, (April 1, 1990). Department of Classics, UCB. Cabinet of the Muses: Rosenmeyer Festschrift. Paper festschrift18.

- Seaford, Richard. Dionysos (Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World). Oxford: Routledge, 2006 ISBN 0-415-32487-4.

- Taylor-Perry, Rosemarie The God Who Comes: Dionysian Mysteries Revisited. New York: Algora Press, 2003 ISBN 0-87586-214-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dionysus. |

- Theoi Project, Dionysos myths from original sources, cult, classical art

- Ca 2000 images of Bacchus at the Warburg Institute's Iconographic Database

- Iconographic Themes in Art: Bacchus | Dionysos

- Thomas Taylor's treatise on the Bacchic Mysteries

- Dionysos Links and Booklist (A huge list of links.)

- Mosaic of Dionysus at Ephesus Terrace Home-2

- The birth of Dionysus from the thigh of Zeus - Volute crater from Apulia

| ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||