Digital root

The digital root (also repeated digital sum) of a non-negative integer is the (single digit) value obtained by an iterative process of summing digits, on each iteration using the result from the previous iteration to compute a digit sum. The process continues until a single-digit number is reached.

For example, the digital root of 65,536 is 7, because 6 + 5 + 5 + 3 + 6 = 25 and 2 + 5 = 7.

Digital roots can be calculated with congruences in modular arithmetic rather than by adding up all the digits, a procedure that can save time in the case of very large numbers.

Digital roots can be used as a sort of checksum. For example, since the digital root of a sum is always equal to the digital root of the sum of the summands' digital roots. A person adding long columns of large numbers will often find it reassuring to apply casting out nines to his result—knowing that this technique will catch the majority of errors.

Digital roots are used in Western numerology, but certain numbers deemed to have occult significance (such as 11 and 22) are not always completely reduced to a single digit.

The number of times the digits must be summed to reach the digital sum is called a number's additive persistence; in the above example, the additive persistence of 65,536 is 2.

Significance and formula of the digital root

It helps to see the digital root of a positive integer as the position it holds with respect to the largest multiple of 9 less than it. For example, the digital root of 11 is 2, which means that 11 is the second number after 9. Likewise, the digital root of 2035 is 1, which means that 2035 − 1 is a multiple of 9. If a number produces a digital root of exactly 9, then the number is a multiple of 9.

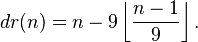

With this in mind the digital root of a positive integer  may be defined by using floor function

may be defined by using floor function  , as

, as

Abstract multiplication of digital roots

The table below shows the digital roots produced by the familiar multiplication table in the decimal system.

| dr | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 |

| 2 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 8 | 1 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 9 |

| 3 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 9 | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| 4 | 4 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 2 | 6 | 1 | 5 | 9 |

| 5 | 5 | 1 | 6 | 2 | 7 | 3 | 8 | 4 | 9 |

| 6 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 9 | 6 | 3 | 9 |

| 7 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 1 | 8 | 6 | 4 | 2 | 9 |

| 8 | 8 | 7 | 6 | 5 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 9 |

| 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 9 |

The table shows a number of interesting patterns and symmetries and is known as the Vedic square.

Formal definition

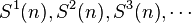

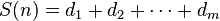

Let  denote the sum of the digits of

denote the sum of the digits of  and let the composition of

and let the composition of  as follows:

as follows:

Eventually the sequence  becomes a one digit number. Let

becomes a one digit number. Let  (the digital sum of

(the digital sum of  ) represent this one digit number.

) represent this one digit number.

Example

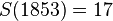

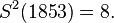

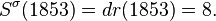

Let us find the digital sum of  .

.

Thus,

For simplicity let us agree simply that

Proof that a constant value exists

How do we know that the sequence  eventually becomes a one digit number? Here's a proof:

eventually becomes a one digit number? Here's a proof:

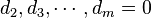

Let  , for all

, for all  ,

,  is an integer greater than or equal to 0 and less than 10. Then,

is an integer greater than or equal to 0 and less than 10. Then,  . This means that

. This means that  , unless

, unless  , in which case

, in which case  is a one digit number. Thus, repeatedly using the

is a one digit number. Thus, repeatedly using the  function would cause

function would cause  to decrease by at least 1, until it becomes a one digit number, at which point it will stay constant, as

to decrease by at least 1, until it becomes a one digit number, at which point it will stay constant, as  .

.

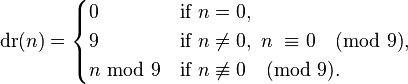

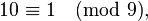

Congruence formula

The formula is:

or,

To generalize the concept of digital roots to other bases b, one can simply change the 9 in the formula to b - 1.

The digital root is the value modulo 9 because  and thus

and thus  so regardless of position, the value mod 9 is the same –

so regardless of position, the value mod 9 is the same –  – which is why digits can be meaningfully added. Concretely, for a three-digit number,

– which is why digits can be meaningfully added. Concretely, for a three-digit number,

To obtain the modular value with respect to other numbers n, one can take weighted sums, where the weight on the kth digit corresponds to the value of  modulo n, or analogously for

modulo n, or analogously for  for different bases. This is simplest for 2, 5, and 10, where higher digits vanish (since 2 and 5 divide 10), which corresponds to the familiar fact that the divisibility of a decimal number with respect to 2, 5, and 10 can be checked by the last digit (even numbers end in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8).

for different bases. This is simplest for 2, 5, and 10, where higher digits vanish (since 2 and 5 divide 10), which corresponds to the familiar fact that the divisibility of a decimal number with respect to 2, 5, and 10 can be checked by the last digit (even numbers end in 0, 2, 4, 6, or 8).

Also of note is the modulus 11: since  and thus

and thus  taking the alternating sum of digits yields the value modulo 11.

taking the alternating sum of digits yields the value modulo 11.

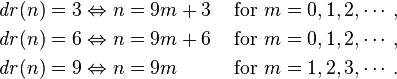

Some properties of digital roots

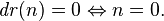

The digital root of a number is zero if and only if the number is itself zero.

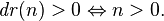

The digital root of a number is a positive integer if and only if the number is itself a positive integer.

The digital root of n is n itself if and only if the number has exactly one digit.

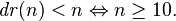

The digital root of n is less than n if and only if the number is greater than or equal to 10.

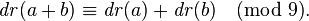

The digital root of a + b is congruent with the sum of the digital root of a and the digital root of b modulo 9.

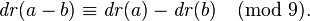

The digital root of a - b is congruent with the difference of the digital root of a and the digital root of b modulo 9.

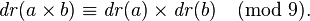

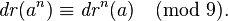

The digital root of a × b is congruent with the multiple of the digital root of a and the digital root of b modulo 9.

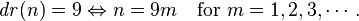

- The digital root of a nonzero number is 9 if and only if the number is itself a multiple of 9.

- The digital root of a nonzero number is a multiple of 3 if and only if the number is itself a multiple of 3.

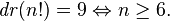

- The digital root of a factorial ≥ 6! is 9.

- The digital root of a square is 1, 4, 7, or 9. Digital roots of square numbers progress in the sequence 1, 4, 9, 7, 7, 9, 4, 1, 9.

- The digital root of a perfect cube is 1, 8 or 9, and digital roots of perfect cubes progress in that exact sequence.

- The digital root of a prime number (except 3) is 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, or 8.

- The digital root of a power of 2 is 1, 2, 4, 5, 7, or 8. Digital roots of the powers of 2 progress in the sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 7, 5. This even applies to negative powers of 2; for example, 2 to the power of 0 is 1; 2 to the power of -1 (minus one) is .5, with a digital root of 5; 2 to the power of -2 is .25, with a digital root of 7; and so on, ad infinitum in both directions. This is because negative powers of 2 share the same digits (after removing leading zeroes) as corresponding positive powers of 5, whose digital roots progress in the sequence 1, 5, 7, 8, 4, 2.

- The digital root of a power of 5 is 1, 2, 4, 5, 7 or 8. Digital roots of the powers of 5 progress in the sequence 1, 5, 7, 8, 4, 2. This even applies to negative powers of 5; for example, 5 to the power of 0 is 1; 5 to the power of -1 (minus one) is .2, with a digital root of 2; 5 to the power of -2 is .04, with a digital root of 4; and so on, ad infinitum in both directions. This is because the negative powers of 5 share the same digits (after removing leading zeroes) as corresponding positive powers of 2, whose digital roots progress in sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 7, 5.

- The digital roots of powered numbers progress in sequence (only certain for positive powers, although in for some exceptions it also may occur for negative powers), and this is because of one of the previously shown properties. As the digital root of a b is congruent with the multiple of the digital root of a and the digital root of b modulo 9, the digital root of a a will also do it. So, for example, as shown above, powers of 2 will follows the sequence 1, 2, 4, 8, 7, 5; Powers of 29 (whose digital root is 2) will also follow this sequence. The very sequence follows this rule, and is appliable to any othe number.

- The digital root of an even perfect number (except 6) is 1.

- The digital root of a centered hexagram, or star number is 1 or 4. Digital roots of star numbers progress in the sequence 1, 4, 1.

- The digital root of a centered hexagon number is 1 or 7, their digital roots progressing in the sequence 1, 7, 1.

- The digital root of a triangular number is 1, 3, 6 or 9. Digital roots of triangular numbers progress in the sequence 1, 3, 6, 1, 6, 3, 1, 9, 9, which is palindromic after the first eight terms.

- The digital root of Fibonacci numbers is a repeating pattern of 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 4, 3, 7, 1, 8, 9, 8, 8, 7, 6, 4, 1, 5, 6, 2, 8, 1, 9.

- The digital root of Lucas numbers is a repeating pattern of 2, 1, 3, 4, 7, 2, 9, 2, 2, 4, 6, 1, 7, 8, 6, 5, 2, 7, 9, 7, 7, 5, 3, 8.

- The digital root of the product of twin primes, other than 3 and 5, is 8. The digital root of the product of 3 and 5 (twin primes) is 6.

See also

References

- F. M. Hall: An Introduction into Abstract Algebra. 2nd edition, CUP ARchive 1980, ISBN 978-0-521-29861-2, p. 101 (online copy, p. 101, at Google Books)

- Bonnie Averbach, Orin Chein: Problem Solving Through Recreational Mathematics. Courier Dover Publications 2000, ISBN 0-486-40917-1, pp. 125–127 (online copy, p. 125, at Google Books)

- Talal Ghannam: The Mystery of Numbers: Revealed Through Their Digital Root. CreateSpace Publications 2012, ISBN 978-1477678411, pp. 68–73

- T. H. O'Beirne: Puzzles and Paradoxes. In: New Scientist, No. 230, 1961-4-13, pp. 53–54 (online copy, p. 53, at Google Books)¨