Digital divide in the United States

The digital divide in the United States refers to actual or perceived inequalities between individuals, households, and other groups of different demographic and socioeconomic levels in access to information and communication technologies ("ICTs") and in the knowledge and skills needed to effectively use the information gained from connecting.[1][2][3] The global digital divide refers to inequalities in access, knowledge, and skills, but designates countries as the units of analysis and examines the divide between developing and developed countries on an international scale.[4]

Trends in access and usage

The National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA) conducted the first survey to assess Internet usage among what the study deemed the 'haves' and the 'have-nots' of American society in 1995.[2] After U.S. President Bill Clinton adopted the phrase, "the digital divide" in his 2000 State of the Union address, researchers have identified numerous origins and aversions explaining trends in access and usage of information and communication technologies between the groups of United States' haves and have-nots.[5] Over the past decade, several of these demographic access and usage gaps have narrowed, or closed altogether, while others continue to show a lack of connectivity for the group; these include gaps on the basis of race and ethnicity and income.[6][7] The digital divide has been identified by policymakers as a concern in need of a remedy, since technology has the potential to improve individual Americans' lives.[7] Although frequency of Internet use among all Americans has risen (26% in 2002 used the Internet for more than an hour per day compared to 48% in 2009), still almost one third of Americans are not connected to the Internet.[6][8] Internet connectivity varies widely state by state in the U.S., as well. For example, in 2011 89% of Washington residents were connected to the Internet in one or more locations on one or more devices, ranking first in the nation.[9] Meanwhile 59% of all Mississippi residents were connected to the Internet in one or more locations on one or more devices in 2011, ranking last in the nation.[10] In addition to a divide in access to connectivity, researchers have identified a skill, or knowledge, divide that demonstrates a gap between groups in the United States on the basis of technological competency and digital literacy.[11]

The effort by the United States' government to close the digital divide has included private and public sector participation, and has developed policies to address information infrastructure and digital literacy that promotes a digital society in the United States.[12]

Demographic breakdown

Gender

By 2001, women had surpassed men as the majority of the online United States population. 2009 Census data suggests that potential disparities in gendered connectivity have become nearly nonexistent; 73% of female citizens three years and older compared to 74% of males could access the Internet from their home.[13][14] When controlling for income, levels of education, and employment, it turns out that women are clearly more enthusiastic ICT users than men.[15]

Age

Older generations of Americans have consistently reported the lowest level of access to the Internet per age cohorts.[16] Americans 55 and older have always shown the lowest level of broadband usage, while Americans ages 18–24 have exhibited the highest levels of usage: in 2001, 3.1% of households 65 years and older, 10.1% of households 45–64 years of age, and 11.3% of households 16–44 years of age connected to the Internet at home.[17] The same trend holds true on the individual level: in 2005, 26% of Americans ages 65+, 67% of ages 50–64, 80% of ages 30–49, and 84% of ages 18–29 reported Internet access.[18] As a whole, usage rates are increasing, but older Americans still have the lowest levels of Internet connectivity: by 2009, 39.9% of households 65 years and older, 68.2% of households 45-64, and 71.2% of households 16-44 reported connecting to the Internet.[17] Per the oldest generations of Americans, 4% of the GI Generation (85+), 7% of the Silent Generation (66-84), and 35% of the Baby Boomers (47-65) had connected to the Internet by February 2008.[19][20]

Race and ethnicity

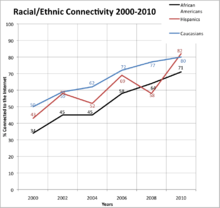

Generally, racial minorities have demonstrated lower levels of access and knowledge ICTs and of owning infrastructure to utilize the connection.[21] The gap between races has been evident for over a decade: in 2000, 50% of Whites had access to the Internet compared to 43% of Hispanics and 34% of African Americans.[22] As of 2009, 77.3% of Asian Americans, 68% of Whites, 49.4% of Blacks, and 47.9% of Hispanics used broadband at home.[17] Even though the racial gap in Internet connectivity and usage is still evident, it is narrowing, as racial minorities experience a higher growth rate than majorities.[23]

81% of U.S. born Latinos versus 54% of U.S. foreign-born Latinos used the Internet in 2010.[24] Of all adults, English-speaking Hispanics are the fastest rising ethnic cohort in terms of Internet usage.[25] In 2010, 81% of English-dominant Latinos, 74% bilingual Latinos, and 47% Spanish-dominant Latinos use the Internet. Even though the rate of dominant Spanish-speaking Latinos is low, comparatively, it has risen significantly since 36% in 2009.[24]

African Americans are behind Whites in Internet access, but the gap is most evident within the senior population: in 2003, 11% of African Americans age 65 and older reported using the Internet, compared to 22% of senior Whites. Also in 2003, 68% of 18-24 year old African Americans and 83% of 18-24 year old Whites had Internet access. A similar gap is noted in the 55-64 year old range with 58% of Whites and 22% of African Americans accessing the Internet.[26]

Finally, between 2000 and 2010, the racial population of Internet users has become increasingly similar to the racial makeup of the United States population, demonstrating a closing racial divide.[27]

By 2011 Internet usage by Hispanics had surpassed that of Black households. 58.3% of Hispanic households in the US have Internet access, while only 56.9% of Black households have access to the web. These numbers are actually down from 2010 when 59.1% of Hispanic homes and 58.1% of Black homes had Internet access. This is in a year when more households had than ever before. In 71.7% of American households had Internet access. The recent downturn might be caused by the recent recession. Even with minor changes such as these, the Internet gap between races does not appear to be shrinking. The races generally continue to have growing Internet usage at about the same rate, thus keeping the gap the same. For example in 2000 the percentage difference between White non-Hispanics and Hispanics and Blacks was about 23% by 2011 this number had shrank to 19%. This however is a relatively small change. [28]

Region

Internet connectivity also varies a lot by State. In a 2011 census, the percentage of people with no Internet connectivity and no computer in the home was recorded. Utah reported the highest rate of Internet access, with only 7.5% reporting no connectivity. Mississippi reported the lowest rate of access, with 26.8% of people reporting no connectivity. As a general trend it is easy to see that Appalachian and Southern States in general have a much lower rate of Internet usage when compared to other regions. This correlates greatly with the average income of those states. Lower income states reporting lower rates of usage, and higher income states reporting higher rates of connectivity. Also it may be a matter of population density. There are a lot more disconnected individuals in states with many counties of low population density. This could be because Internet Service Providers are less likely to make a profit in these areas. [28]

Income

Household income and Internet use are strongly related.[24] In 2010, 57% of individuals earning less than $30,000, 80% of individuals earning $30,000 - $49,999, 86% of individuals earning $50,000 - $74,999, and 95% of individuals earning $75,000 and more used the Internet.[29]

In 2010, 57% of Latinos living in <$30,000 household incomes used the Internet. 79% of all Latinos in households who earn between $30,000 and $49,999 per year were connected to the Internet in 2010. 91% of Latino households earning $50,000 or more per year were connected to the Internet in 2010. 59% of Whites who earned less than $30,000 per year used the Internet, followed by 82% of Whites who earned $30,000 - $49,999, and 92% of Whites who earned $50,000 or more. For African Americans, 54% who earned less than $30,000 connected to the Internet, 88% who earned $30,000 to $49,999, and 89% who earned $50,000 or more.[24]

Educational attainment

In 2008, 44% of high school graduates were internet users, while 91% of college graduates were internet users.[30] In 2004, higher numbers of educated seniors had connected to the Internet: 62% of all connected seniors had at least some college education.[26]

46% of Whites online in 2010 reported no high school diploma, compared to 43% of Blacks and 42% of Hispanics who had no diploma. 68% of Hispanics who graduated from high school are online, compared to 64% of Whites and 58% of Blacks. Finally, 91% of Hispanics who received some college education or more are online, with 90% of Whites and 84% of Blacks achieving some college education or more are also connected.[24]

Reasons given for trends and gaps

Much of the growth in the Latino adult Internet population can be accounted for by examining the differential usages of U.S.-born Latinos versus foreign-born Latinos and the primary language used.

Some studies suggest an interaction effect between race and income in predicting Internet connectivity.[24][31]

There are also different levels of connectivity between Whites and Hispanics that are attributable to education as well as income, since Hispanics tend to have less education and lower income than Whites.

Means of connectivity

Infrastructure

The infrastructure by which individuals, households, businesses, and communities connect to the Internet refers to the physical mediums that people use to connect to the Internet such as desktop computers, laptops, cell phones, iPods or other MP3 players, Xboxes or PlayStations, electronic book readers, and tablets such as iPads.[32] Other than desktops, most types of Internet capable infrastructure connect through wireless means. In 2009, 56% of Americans said that they had connected to the Internet through wireless means.[25]

Within the G.I. generation (75 years and older), 28% own desktop and 10% own laptops. Of the Silent Generation (66–74 years), 48% own desktops and 30% own laptops. 64% of the Older Baby Boomers (57–65 years) own desktops and 43% own laptops. 65% of the Younger Boomers (47–56 years) own desktops and 49% own laptops. 69% of Generation X (35–46 years) owns desktops and 61% owns laptops. Generation Y (or the Millennials) are the only generation whose laptop use exceeds desktop use of 70% to 57%, relatively. Of adults over 65, only 45% have a computer (40% of adults 65 and older use the Internet).[32]

85% of all adults 18 and over own a cell phone, such as a Blackberry or iPhone, or other device that serves as a cell phone. Broken up into age cohorts, 48% of ages 75 and older, 68% of 66-74 year olds, 84% of 57-65 year olds, 86% of 47-56 year olds, 92% of 35-46 year olds, and 95% of 18-34 year olds own a cell phone, such as a Blackberry of iPhone, or other device that serves as a cell phone.[32]

Of each individual within the age cohort who owns a cell phone, such as a Blackberry or iPhone, or other device that serves as a cell phone, 2% of adults 75 and older, 17% of adults ages 66–74, 15% of ages 57–65, 25% of 47-56 year olds, 42% of 35-46 year olds, and 63% of 18-34 year olds use their phone to access the Internet.[32]

Racial minorities use cell phones more often than any other device to connect to the Internet. In 2010, 76% of Hispanic, 79% of Black, and 85% of White adults were using cell phones. 34% of White cell phone owners, 40% of Hispanic cell phone owners, and 51% of Black cell phone owners use their phones to access the Internet.[24]

47% of all adults own an iPod or MP3 player. 3% of 75+, 16% of ages 66–74, 26% of ages 57–65, 42% of ages 47–56, 56% of ages 35–46, and 74% of ages 18–34 own an iPod or MP3 player.[32] Similarly, 42% of adults own a game console such as an Xbox or PlayStation. 3% of adults 75 and older, 8% of the adults ages 66–74, 19% of adults ages 57–65, 38% of adults ages 47–56, 63% of adults ages 35–46 and 18-34 own a game console.

Adult age cohorts owning e-Book readers and iPads or tablets are similar percentages as well. 5% of all adults own an e-Book reader compared to 4% owning an iPad or tablet. 2% of adults ages 75 + own an e-Book compared to 1% owning a tablet, 6% of 66-74 year olds own an e-Book compared to 1% owning a tablet, 3% of adults ages 57–65 own an e-book reader and an iPad or tablet, 7% of adults ages 47–56 own an e-Book reader compared to 4% owning an iPad or tablet, and 5% of adults ages 18–46 own an e-Book reader and an iPad or tablet.[32]

Age is negatively related to incidence of owning a device: 1% of 18-34 year olds, 3% of 35-46 year olds, 8% of 47-56 year olds, 20% of 66-74 year olds, and 43% of 75 year olds and older own none of the previously listed devices.[32]

Location

Internet connectivity can be accessed at a variety of locations such as homes, offices, schools, libraries, public spaces, Internet cafes, etc.[24]

Of the 88% of individuals who connected on their laptop or netbook to a wireless connection, 86% used the device at home, 37% at work, and 54% somewhere else other than home or work.[33]

A digital divide was noted between urban and rural areas by the NTIA in 1999, but more recently that gap has closed.[34] Currently, Environmental racism may account for some of the disparities in Internet access between residentially segregated areas according to race. The difference in Internet access and skill level can be explained by racial segregation and concentrated poverty, resulting in restricted options and availability of networks to connect to the Internet and use of ICTs.[21]

Purpose of connectivity

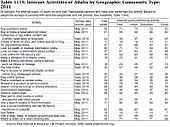

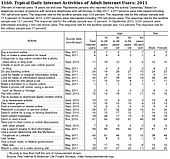

As new applications and software is developed, the Internet has increasingly become utilized to complete a variety of both professional work and personal tasks. To the right of this section are two tables describing the most recent data on the types of activities U.S. citizens utilize the Internet for compiled by the U.S. Census Bureau and presented in its final Statistical Abstract of the United States: 2012.

41% of Blacks and 47% of English-speaking Hispanics send and receive email on cell phones, as compared to 30% of Whites. Significant differences between the racial groups include sending and receiving instant messages, using social networking sites, watching videos, and positing photos or videos online.[35]

A 2013 study found that "African Americans are more likely than other segments of the population to use the Internet to seek and apply for employment, and are more likely to consider the Internet very important to the success of their job search."[36]

Lack of connectivity

Physical, financial, psychological, and skill-based barriers exist in terms of Internet access and Internet skills for different demographics:

25% of American adults live with a disability that interferes with daily living activities. 54% of adults living with a disability still connect to the Internet. 2% of adults say they have a disability or illness that makes it more difficult or impossible for them to effectively and efficiently use the Internet.[37]

Aversion to the Internet influences an individual's psychological barriers to Internet usage, affecting which involving which individuals connect and for what purpose. Comfort displayed toward technology can be described as comfort performing a task concerning the medium and infrastructure by which to connect. Technological infrastructure sometimes causes privacy and security concerns leading to a lack of connectivity.[38]

Individuals that exhibit computer anxiety demonstrate fear towards the initial experience of computer usage or the process of using a computer. From this, many researchers conclude that increased computer experience could lead to lower anxiety levels. Others suggest that individuals demonstrate anxiety towards specific computer tasks, such as using the Internet, rather than anxiety towards computers in general.[39]

Communication apprehension influences propensity to use only Internet applications that promote engagement in communication with other people such as Skype or iChat.[40]

Overcoming the digital divide in the United States

Information infrastructure

Congress passed the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act on February 13, 2009 which was signed it into law four days later by President Barack Obama.[41] A portion of the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act designated approximately $7.2 billion in investments to expand broadband access nationwide, improve high-speed connectivity in rural areas and public computer centers, and increase Internet capacity in schools, libraries, public safety offices, and other public buildings.[42][43]

According to a joint report from The Alliance for the Public Technology and the Communications Workers of America released in July 2008, states developed initiatives before there had been any national-wide action aimed to actively develop an information infrastructure and start to catch up to other countries in respect to the number of households with broadband internet. Broadband initiatives by the states can be broadly classified into seven different types:

- “Broadband Commissions, Task Force, or Authority established through legislation or executive order that directs public and private stakeholders to assess the state of high-speed Internet deployment and adoption in the state and recommend policy solutions.

- Public-Private Partnerships convened through executive order or statute to broadband availability, identify unserved and underserved areas, assess supply and demand-side barriers, create local technology teams to implement programs to increase computer ownership, digital literacy, aggregate demand, and accelerate broadband build-out.

- Direct Funding Programs to support the build-out of advanced networks in unserved and underserved areas by leveraging private sector funds to make network investment – and thus Internet service – more affordable

- State Networks operated by public agencies or the private sector connecting schools, universities, libraries and state and local government agencies to reduce costs by aggregating demand. In some cases, public agencies serve as anchor tenants to make middle-mile broadband build-out to underserved communities more economic. At least 30 states have established state networks

- Telehealth networks linking rural clinics with specialists in hospitals and academic institutions. At least 25 states support state telehealth networks.

- Tax Policy with targeted tax incentives for investment in broadband equipment.

- Demand-Side Programs to promote computer ownership, digital literacy, and development of community-based applications and services."[44]

Notable Initiatives

In 1993, the U.S. Advisory Council on the National Information Infrastructure was established and administered a report called A Nation of Opportunity that planned access to ICTs for all member of the population and emphasized the government's role in protecting their existence.[45]

Founded in 1996, the Boston Digital Bridge Foundation [46] attempts to enhance children's and their parents' computer knowledge, program application usage, and ability to easily navigate the Internet. In 2010, the City of Boston received a 4.3 million dollar grant from the National Telecommunications and Information Administration. The grant will attempt to provide Internet access and training to underserved populations including parents, children, youth, and the elderly.[47]

Starting in 1997, Cisco Systems Inc. began Cisco Networking Academy which donated equipment and provided training programs to high schools and community centers that fell in U.S. Empowerment Zones.[12]

Since 1999, a non-profit organization called Computers for Youth has provided cheaper Internet access, computers, and training to minority homes and schools in New York City. Currently, the agency serves more than 1,200 families and teachers per year.[48]

The Tomorrow's Teachers to Use Technology established by the Department of Education was given almost $400 million between 1999 and 2003 to train teachers in elementary and secondary schools to use ICTs in the classroom.[12]

In 2000, Berkeley, California established a program that facilitated digital democracy in allowing residents to contribute opinions to general city plans via the Internet.[11]

The National Science Foundation gave EDUCAUSE (a non-profit that attempts to enhance education with ICTs) $6 million to focus on providing ICTs to Hispanic-Serving Institutions, Historically Black Colleges and Universities, and Tribal Colleges and Universities.[49]

In 2000, President Clinton allocated $2.34 billion to provide low-income families at-home access to computers and the Internet, to install broadband networks in underserved communities, and to encourage private donation of computers, businesses or individuals to sponsor community technology centers, and technology training. An additional $45 million was added to emphasize provision of ICTs to underserved areas.[50]

In 2003, the Gates Foundation contributed $250 million to install more than 47,000 computers and train librarians in almost 11,000 libraries in all 50 states.[51]

In 2004 in Houston, Texas, a non-profit organization called Technology for All (TFA) established a free broadband Wi-Fi network in an underserved community, Pecan Park. An additional grant in 2010 assisted TFA, in collaboration with Rice University, in upgrading their Wi-Fi network to a new long-range version, a "Super Wi-Fi" in order to enhance network speed and computer quality.[52]

In June 2004, Hon. Gale Brewer (D-Manhattan), Chair of the Select Committee on Technology in Government (now the Committee on Technology)[53] in conjunction with a graduate student Digital Opportunities Team at CUNY Hunter College, supervised by Professor Lisa Tolliver in the Departments of Urban Affairs and Planning[54]), published a study and recommendations titled Expanding Digital Opportunity in New York City Public Schools: Profiles of Innovators and Leaders Who Make a Difference.[55] The report was one of numerous initiatives and events implemented by the Select Committee, which includes roundtables, conferences, hearings, and collaborative partnerships.[56]).[57]

In 2007, projects called One Laptop per Child, Raspberry Pi and 50x15 were implemented in attempting to reduce the digital divide by providing cheaper infrastructure necessary to connect.[58]

In 2007, the use of “hotspot”[59] zones (people can access free Wi-Fi) was introduced to help bridge access to the Internet. Due to a majority percentage of American adults (55) connecting wirelessly, this policy can assist in providing more comprehensive network coverage, but also ignores an underprivileged population of people who do not own infrastructure, so still lack access to the Internet and ICTs.[59]

The Broadband Access ($76 billion) and Community Connect ($57.7 million in grants) programs administered by the US Department of Agriculture (2007) and the e-Rate program administered by the Federal Communications Commission are the pillars of national policies intended to promote the diffusion of broadband Internet service in rural America.[60]

Since 2008, organizations such as Geekcorps [61] and Inveneo [62] have been working to reduce the digital divide by emphasizing ICTs within a classroom context. Technology used often includes laptops, handhelds (e.g. Simputer, E-slate), and tablet PCs.[63]

In 2011, Congresswoman Doris Matsui introduced the Broadband Affordability Act, which calls for the U.S. Federal Communications Commission (FCC) to subsidize broadband Internet service for low-income citizens, assisting in closing the gap between high-income and low-income households. The Act would expand the program to offer discounted internet service to lower-income consumers living in both urban and rural areas.[64]

Digital literacy

Digital literacy has been defined as: "The ability to use digital technology, communication tools or networks to locate, evaluate, use and create information. The ability to understand and use information in multiple formats from a wide range of sources when it is presented via computers. A person’s ability to perform tasks effectively in a digital environment... Literacy includes the ability to read and interpret media, to reproduce data and images through digital manipulation, and to evaluate and apply new knowledge gained from digital environments.”[65][66][67]

Developing issues regarding digital literacy in the 21st century do not necessarily only pertain to the binary ability or inability or lack of computer skills anymore as the utilization of computers and other electronic/digital communication devices and heavy adoption of internet resources has steadily increased over the past couple of decades.[68][69] Due to the exponentially increasing computing power of electronic devices becoming commercialized a new type of digital divide between the new generation of “media-savvy, multitasking” youth and their preceding generation(s) has emerged which has been coined the Knowledge Divide.[70]

Currently, much of the developed digital literacy levels attained derive from self-exploration and learning by doing. A majority of people also acquire information technology skills from required school coursework or from their workplace.[70]

Some strategies proposed to help react to this new form of the digital divide include providing digital literacy workshops for parents and educators who may have fallen behind the computer skill level of their children and/or pupils.[71] Other proactive strategies include developing preservice teachers to ‘think with technology’ with minimum threshold standards that include:

- "Demonstrating a sound understanding of technology operations and concepts.

- Planning and designing effective learning environments and experiences supported by technology.

- Implementing curriculum plans that include methods and strategies for applying technology to maximize student learning.

- Applying technology to facilitate a variety of effective assessment and evaluation strategies.

- Using technology to enhance their productivity and professional practice.

- Understanding the social, ethical, legal, and human issues surrounding the use of technology in PreK through 12 schools and apply that understanding in practice." [72]

Some groups have proposed changing traditional English or writing class curricula to integrate lessons on digital literacy and teach their students how to navigate through our increasingly more digital and information technology integrated environments to potentially provide an educational safety net for students who may not have as capable electronic devices or as fast or speedy broadband connections as others. There is also a general consensus on the emphasis of improving existing resources within public libraries and schools to keep citizens up to par with the ever-increasing speeds and capabilities of new technology and further expansion and development of the Internet.[71][73]

Digital society

A digital society can have a variety of different meanings in a variety of contexts. For the purpose of this page, a digital society can be seen to be synonymous to an information society which according to László Z. Karvalics, a digital or information society defined as "A new form of social existence in which the storage, production, flow, etc. of networked information plays the central role."[74] In a digital society there exist newly combined institutions for government and the economy denoted respectively as e-government and e-commerce. Both utilize electronic resources and tools to eliminate the geographical barriers for communication and making transactions between citizens and their respective government entities and businesses.

In the U.S., despite the Internet becoming commercially available to American citizens in 1995, a national official government task force “targeted at improving the quality of services to citizens, businesses, governments and government employees, as well as the effectiveness and efficiency of the federal government” was not established until July 2001.[75] This task force then helped to pass the E-Government Act of 2002 which legislatively aimed to “[establish] a broad framework of measures that require using Internet-based information technology to enhance citizen access to Government information and services.”[76] The specific improvements the task force intended to make with the United States federal government included:

- "Simplifying delivery of services to citizens;

- Eliminating layers of government management;

- Making it possible for citizens, businesses, other levels of government and federal employees to easily find information and get service from the federal government;

- Simplifying agencies' business processes and reducing costs through integrating and eliminating redundant systems;

- Enabling achievement of the other elements of the President’s Management Agenda; and

- Streamlining government operations to guarantee rapid response to citizen needs”[75]

The means by which e-government becomes established on the local/city/county level, state, and national level all vary but can be more easily described with “a broad model with a three-phase and dual-pronged strategy for implementing electronic democracy [as] proposed by Watson and Mundy.” [77] The first phase consists of the initiating the utilization of the internet and electronic tools and resources to enable such things as web-based payment. The second phase consists of mass infusion of digital utilization such that citizens are enabled to routinely obtain presentation, reviews, and make government payments online as well as have open access to government information such as city council minutes and/or news on newly enacted legislation or public notices. The third phase consists of citizen customization where ideas become intertwined in discussion over whether the structure of government institutions is and/or should persist to be fundamentally hierarchical or can be better modeled by a simple hub-and-spoke sort of complex social network.[77]

The Federal Communication Commission has projected that expanding access and broadband services in the United States would cost about $350 billion.[78]

The United States’ most recent efforts to help improve the ubiquity and efficiency of e-government on the national level include Executive Order 13571 (Streamlining Service Delivery and Improving Customer Service), Executive Order 13576 (Delivering an Efficient, Effective, and Accountable Government), the President’s Memorandum on Transparency and Open Government, OMB Memorandum M-10-06 (Open Government Directive), the National Strategy for Trusted Identities in Cyberspace (NSTIC), and the 25-Point Implementation Plan to Reform Federal Information Technology Management (IT Reform). These efforts have been outlined and summarized to describe how they each will contribute to achieving the overall goals and reasons for developing e-government by the Digital Government Strategy made available online on May 23, 2012.[79]

E-commerce has made a distinct impact on the United States economy as it has outpaced the overall economy growth based on year-to-year percentage change, accounting for 4.4 percent of total retail sales in 2010 and an estimated $169 billion, an increase from $145 billion in 2009.<ref name:"ESTAT">U.S. Census Bureau. "E-Stats" Report. May 10, 2012. <http://www.census.gov/econ/estats/2010/2010reportfinal.pdf></ref> Since the year 2000 through 2010 the percent of total of retail sales that can be held accountable for by various methods of e-commerce has been steadily increasing in linear fashion and has been projected to reach levels around $254.7 billion.[80] The utilization of e-commerce has become so rampant that legislation on taxing products bought from the internet within the United States has been established such that taxes are taken from products bought online if there exists a nexus within the state the product is received in.<ref name:"tax">U.S. Small Business Administration. "Collecting Sales Tax Online".<http://www.sba.gov/content/collecting-sales-tax-over-internet></ref>

E-commerce is one of the solutions proposed by many groups that may help improve the lack of information technology adoption within rural communities. Prior experience with the Internet, the expected outcomes of broadband usage, direct personal experience with broadband, and self-efficacy as well as age and income have been found to have direct effects on broadband intentions.[60] Taking these factors into account, successful methods of presenting how information and communication technology can improve the livelihoods of rural community citizens will most likely depend on promotional efforts made by rural community institutions that connect potential users with previous broadband adopters to stress the benefits of broadband usage and bolster the self-efficacy of novices.[60]

Implications

Social capital

The majority of research on civic engagement and social capital shows that the Internet enhances social capital in the United States, but others report that after controlling for background variables, civic engagement between users and non-users is not significantly different.[81]

Of those who do believe that the Internet promotes social capital, a longitudinal study in Pittsburgh found that Internet usage increased rates of individual participation in community activities as well as levels of trust. Additionally, these increased levels of involvement were greater for participants who had previously been the least involved.[82] Of those who use the Internet in the United States, studies have found that these individuals tend to be members of community social networks, participate in community activities, and exhibit higher levels of political participation.[83]

Economic gains

The United States is the world leader in Internet supply ecosystem, holding over 30% of global Internet revenues and more than 40% of global Internet net income. Its lead primarily stems from the economic importance of and dependence the United States places on the Internet, since the Internet makes the United States' economic activity faster, cheaper, and more efficient.[84] The Internet provides a large contribution to wealth: 61% of businesses who use the Internet in the United States saved $155.2 billion as a result of ICTs as more efficient means toward productivity.[85] In 2009, the Internet generated $64 billion in consumer surplus in the United States.[84] In the United States, the Internet promotes private consumption primarily through online shopping. In 2009, online purchases of goods and services totaled about $250 billion, with average consumption per buyer equaling about $1,773 over the year.[84] That same year, the Internet contributed to 60% of the United States' private consumption, 24% of private investment, 20% of public expenditure, and 3.8% of the GDP.[84]

Between 1995 and 2009, the Internet has contributed to 8% of the GDP's growth in the United States. Most recently, the Internet has contributed to 15% of the GDP's growth from 2004-2009.[84] The American government can also communicate more quickly and easily with citizens who are Internet consumers: e-government supports interactions with American individuals and businesses.[86]

Additionally, widespread use of the Internet by businesses and corporations drives down energy costs. Besides the fact that Internet usage does not consume large amounts of energy, businesses who utilize connections no longer have to ship, stock, heat, cool, and light unsellable items whose lack of consumption not only yields less profit for the company but also wastes more energy. Online shopping contributes to less fuel use: a 10 pound package via airmail uses 40% less fuel than a trip to buy that same package at a local mall, or shipping via railroad. Researchers in 2000 predicted a continuing decline in energy due to Internet consumption to save 2.7 million tons of paper per year, yielding a decrease by 10 million tons of carbon dioxide globalwarming pollution per year.[87]

Within the capabilities approach

An individual must be able to connect in order to achieve enhancement of social and cultural capital and achieve mass economic gains in productivity. Even though individuals in the United States are legally capable of accessing the Internet, many are thwarted by barriers to entry such as a lack of means to infrastructure or the inability to comprehend the information that the Internet provides. Lack of infrastructure and lack of knowledge are two major obstacles that impede mass connectivity. These barriers limit individuals' capabilities in what they can do and what they can achieve in accessing technology. Some individuals have the ability to connect, but have nonfunctioning capabilities in that they do not have the knowledge to use what information ICTs and Internet technologies provide them.[88][89]

Criticisms

As is evident by policies enacted, agencies created, and policies administered listed above, the United States has been active in closing the access gap in the digital divide, but studies demonstrate that a digital divide is still present; that is, access is becoming universal, but the skills needed to effectively consume and efficiently use information gained from ICTs are not.[12]

Second level digital divide

The second level digital divide, also referred to as the production gap, describes the gap that separates the consumers of content on the internet from the producers of content.[90] As the technological digital divide is decreasing between those with access to the internet and those without, the meaning of the term digital divide is evolving. Previously, digital divide research has focused on accessibility to the Internet and Internet consumption. However, with an increasing number of the population with access to the Internet, researchers are examining how people use the internet to create content and what impact socioeconomics are having on user behavior.[91] New applications have made it possible for anyone with a computer and an Internet connection to be a creator of content, yet the majority of user-generated content widely available widely on the Internet, like public blogs, is created by a small portion of the Internet-using population. Web 2.0 technologies like Facebook, YouTube, Twitter, and blogs enable users to participate online and create content without having to understand how the technology actually works, leading to an ever increasing digital divide between those who have the skills and understanding to interact more fully with the technology and those who are passive consumers of it.[90] Many are only nominal content creators through the use of Web 2.0, like posting photos and status updates on Facebook, but not truly interacting with the technology. Some of the reasons for this production gap include material factors like what type of Internet connection one has and the frequency of access to the internet. The more frequently a person has access to the Internet and the faster the connection, the more opportunities they have to gain the technology skills and the more time they have to be creative.[92] Other reasons include cultural factors often associated with class and socioeconomic status. Users of lower socioeconomic status are less likely to participate in content creation due to disadvantages in education and lack of the necessary free time for the work involved in blog or web site creation and maintenance.[92] Additionally, there is evidence to support the existence of the second-level digital divide at the K-12 level based on how educators' use technology for instruction.[93] Schools' economic factors have been found to explain variation in how teachers use technology to promote higher-order thinking skills.[94]

Knowledge divide

Since gender, age, racial, income, and educational gaps in the digital divide have narrowed compared to past levels, some researchers suggest that the digital divide is shifting from a gap in access and connectivity to ICTs to a Knowledge divide. A knowledge divide concerning technology presents the possibility that the gap has moved beyond access and having the resources to connect to ICTs, to interpreting and understanding information presented once connected.[95] Generations of youth within the 8 to 18 age range called ‘Generation M’ have grown up alongside the exponential growth of the Internet and personal computer and because of this, in many situations, 'Generation M' has surpassed the technological knowhow of their parents and teachers simply because of their extended experience with technology, which usually started in early stages of life. From their foundational experiences 'Generation M' has developed innovative ideas and products based on these continually improving electronic resources and tools which have helped augment the span and quality of information and knowledge transmission. Thus the digital divide in the United States is no longer just a matter of lack of access as mentioned previously but a sort of race where the generations that created computers and the Internet must now keep up with the improving skill level of ‘Generation M’.[70] The exponential development of ICT has also developed situations where there is a great disparity in ICT skill levels among people of the same generation due to the differences in internet connection speeds in addition to differing levels of access and availability which can dictate the type and overall amount of media and information people are able to consume.

These differing groups can be classified based on ICT skill level by the following or in similar terms:

- Athletes – technophiles; those who are very keen on technology and usually have early adopter or innovator behavior and take pleasure in utilizing the internet and other information technology

- The laidback – those who are attributed with a lack of clarity of the potential benefits of the internet and information technology adoption who mainly use the internet and computers for search and email exchange

- The needy – those who require external help to help develop an initial inertia for starting to use the internet and information technologies in meaningful ways[96]

See also

- Digital divide in China

- Digital divide in South Africa

- Digital Opportunity Index

- Knowledge divide

References

- ↑ Norris, P. 2001. Digital divide: Civic engagement, information poverty and the Internet world- wide. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Univ. Press.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 U.S. Department of Commerce, National Telecommunications and Information Administration (NTIA). 1995. Falling through the net: A survey of the “have nots” in rural and urban America. Retrieved from http://www.ntia.doc.gov/ntiahome/fallingthru.html.

- ↑ Patricia, J.P. 2003. ‘E-government, E-Asean Task force, UNDP-APDIP’. From: http://www.apdip.net/publications/iespprimers/eprimer-egov.pdf

- ↑ Chinn, Menzie D. and Robert W. Fairlie. 2004. “The Determinants of the Global Digital Divide: A Cross-Country Analysis of Computer and Internet Penetration”. Economic Growth Center. Retrieved from http://www.econ.yale.edu/growth_pdf/cdp881.pdf.

- ↑ Nie, Norman H. 2001. “Sociability, Interpersonal Relations, and the Internet: Reconciling Conflicting Findings.” American Behavioral Scientist 45:420-435

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Morales, Lymari. 2009. “Nearly Half of Americans are Frequent Internet Users.” Gallup Poll.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Sautter, Jessica M. Rebecca M. Tippett and S. Philip Morgan. 2010. “The Social Demography of Internet Dating.” Social Science Quarterly 91(2): 554-575.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Commerce. 2011. “Digital Nation.” Washington, DC: National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

- ↑ "Washington Internet Access". Internet Access Local. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ "Mississippi Internet Access". Internet Access Local. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Mossberger, K., C.J. Tolbert, and M. Stansbury. 2003. Virtual inequality: Beyond the digital divide. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Choemprayong, Songphan. 2006. "Closing Digital Divides: The United States' Policies." Libri 56:201-212.

- ↑ Gorski, Paul (2001). "Understanding the digital divide from a multicultural education framework". EdChange Multicultural Pavilion.

- ↑ "Reported internet usage for individuals 3 years and older, by selected characteristics". U.S. Census Bureau. 2009.

- ↑ Hilbert, Martin (November 2011). "Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics". Women's Studies International Forum (Elsevier) 34 (6): 479–489. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2011.07.001. Free access to a pdf of the study.

- ↑ Yi, Zhixian. 2008. “Internet Use Patterns in the United States.” Chinese Librarianship: an International Electronic Journal 25.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 U.S. Department of Commerce. 2010. “Exploring the Digital Nation: Home Broadband Internet Adoption in the United States.” Washington, DC: National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

- ↑ Fox, Susannah. 2005. "Digital Division." Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ↑ Jones, Sydney and Susannah Fox. 2009. "Generations Online in 2009." Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Matt. 2011. "Names of Generations." About.com Geography. Retrieved from: http://geography.about.com/od/populationgeography/qt/generations.htm.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Mossberger, Karen, Caroline J. Tolbert, and Michele Gilbert. 2006. “Race, Place, and Information Technology.” Urban Affairs Review 41:583-620.

- ↑ Lenhart, Amanda, Lee Rainie, Mary Madden, Angie Boyce, John Horrigan, Katherine Allen, and Erin O’Grady. 2003. “The Ever-Shifting Internet Population: A new look at Internet access and the digital divide.” Pew Internet and American Life Project.

- ↑ Fox, Susannah. 2009. "Latinos Online, 2006-2008." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Commentary/2009/December/Latinos-Online-20062008.aspx

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Livingston, Gretchen. 2010. "Latinos and Digital Technology, 2010." Pew Hispanic Center

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Horrigan, John. 2009. "Wireless Internet Use." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2009/12-Wireless-Internet-Use/6-Access-for-African-Americans.aspx?view=all

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 Fox, Susannah. 2004. "22% of Americans age 65 and older go online." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/~/media/Files/Reports/2004/PIP_Seniors_Online_2004.pdf.pdf.

- ↑ Smith, Aaron. 2010. "Technology Trends Among People of Color" Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://pewinternet.org/Commentary/2010/September/Technology-Trends-Among-People-of-Color.aspx

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 2013. "Computer and Internet Use in the United States" US Census Bureau. Retrieved from: http://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/p20-569.pdf

- ↑ Jansen, Jim. 2010, "Use of the internet in higher-income households." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2010/Better-off-households/Overview.aspx

- ↑ 2008. "Degrees of Access." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.slideshare.net/PewInternet/degrees-of-access-may-2008-data?type=powerpoint.

- ↑ Calvert, Sandra L. et al. 2005. “Age, Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Patterns in Early Computer Use: A National Survey.” American Behavioral Scientist 48:590-606.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 32.3 32.4 32.5 32.6 Zickuher, Kathryn. 2011. "Generations and their gadgets." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Generations-and-gadgets/Report/Desktop-and-Laptop-Computers.aspx.

- ↑ Princeton Survey Research Associates. 2010. "Spring Change Assessment Survey 2010." Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://pewresearch.org.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Commerce. 1999. Falling Through the Net: II. National Telecommunications and Information Administration.

- ↑ Smith, Aaron. 2010. "Mobile Access 2010." Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ↑ Horrigan, John B (2013-11). "Broadband and Jobs: African Americans Rely Heavily on Mobile Access and Social Networking in Job Search". Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies. Retrieved 2014-01-30. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Fox, Susannah. 2011. "Americans living with disability and their technology profile". Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Disability.aspx.

- ↑ Rhodes, Lois. “ Barriers to Access.” Evaluating Community Technology Centers. May 2002.

- ↑ Rockwell, Steven C., Loy Singleton. 2002. “The Effects of Computer Anxiety and Communication Apprehension on the Adoption and Utilization of the Internet.” The Electronic Journal of Communication 12, no. 1 & 2.

- ↑ Princeton Survey Research Associates. "Spring Change Assessment Survey 2010." Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project April 29-May 30, 2010 (2010): 1-8. http://pewresearch.org/ (accessed April 4, 2011).

- ↑ The Recovery Accountability and Transparency Board. The Recovery Act. <http://www.recovery.gov/About/Pages/The_Act.aspx>

- ↑ The White House. Issues: Technology - Broadband. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/issues/technology#id-4>

- ↑ Executive Office of the President of the United States - National Economic Council. "Recovery Act Investments in Broadband: Leveraging Federal Dollars to Create Jobs and Connect America". December 2009. <http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/20091217-recovery-act-investments-broadband.pdf

- ↑ The Alliance for Public Technology, Communications Workers of America. State Broadband Initiatives: A Summary of State Programs Designed to Stimulate Broadband Deployment and Adoption. July 2008. <http://www.speedmatters.org/page/-/SPEEDMATTERS/Publications/CWA_APT_StateBroadbandInitiatives.pdf?nocdn=1>

- ↑ United States Advisory Council on the National Information Infrastructure. 1996. A nation of opportunity: Realizing the promise of the information superhighway. Washington, DC.

- ↑ http://www.digitalbridgefoundation.org/ digitalbridgefoundation

- ↑ http://www.cityofboston.gov/news/default.aspx?id=4765 cityofboston

- ↑ Computers for Youth. 2004. Retrieved from: http://www.cfy.org/about.html.

- ↑ National Science Foundation. Advanced Networking Project with Minority-Serving Institutions. 2004. AN-MSI frequently asked questions. Retrieved from: http://www.anmsi.org/faq/faq.asp?Code=AN-MSI.

- ↑ U.S. White House. 2000. "The Clinton-Gore administration: From digital divide to digital opportunity." Retrieved from: http://clinton4.nara.gov/WH/New/digitaldivide/digital1.html.

- ↑ Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. 2003. "Responding to the needs of other. Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Annual Report, 2003." Retrieved from: http://www.gatesfoundation.org/nr/public/media/annualreports/annualreport03/2003_Gates-AR.pdf.

- ↑ Rice University. Office of Public Affairs. Houston Grandmother Is Nation's First Super Wi-Fi User. Latest Press Release. Technology for All, 19 Apr. 2011. Web. 21 Sept. 2011. <http://techforall.org/News/LatestPressRelease/tabid/223/Default.aspx>

- ↑ "About Us". NYC Council Committee on Technology's Blog. Retrieved July 2013.

- ↑ Select Committee on Technology in Government of the New York City Council (June 2004). Thanks and Acknowledgements. p. 19.

the graduate student Digital Opportunities Team at CUNY Hunter College departments of Urban Affairs and Planning was comprised of Danisa Dambrauskas, Kazu Hoshino, Gavin O'Donoghue, and Jennifer Vallone and supervised by Professor Lisa Tolliver in the Departments of Urban Affairs and Planning

- ↑ Select Committee on Technology in Government of the New York City Council (June 2004). Expanding Digital Opportunity in New York City Public Schools: Profiles of Innovators and Leaders Who Make a Difference.

- ↑ "Fall 2003 Hearing and Event Schedule for The New York City Select Committee on Technology in Government, Chaired by Council Member Gale Brewer (D-Manhattan)". Solutions for State and Local Government Technology. Retrieved July 2013.

- ↑ Select Committee on Technology in Government of the New York City Council (June 2004). Expanding Digital Opportunity in New York City Public Schools: Profiles of Innovators and Leaders Who Make a Difference.

- ↑ "Portables to power PC industry". BBC News. 2007-09-27. Retrieved from http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/technology/7006316.stm on 2010-05-01.

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 Thomas, J. (2007, January 16). New Free Software Will Help Close Digital Divide in Education. America. Gov. Retrieved from: http://www.america.gov/st/washfile-english/2007/January/200701160858151cjsamoht0.6452

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 60.2 Robert LaRose, Jennifer L. Gregg, Sharon Strover, Joseph Straubhaar, and Serena Carpenter. 2007. Closing the rural broadband gap: Promoting adoption of the Internet in rural America. Telecommun. Policy 31, 6-7 (July 2007), 359-373. DOI=10.1016/j.telpol.2007.04.004 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2007.04.004

- ↑ http://www.iesc.org/ict-and-applied-technologies.aspx

- ↑ http://www.inveneo.org/

- ↑ http://www.iesc.org/geekcorps

- ↑ http://matsui.house.gov/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=3050

- ↑ Digital Strategy Glossary of Key Terms <http://www.digitalstrategy.govt.nz/Media-Centre/Glossary-of-Key-Terms/>

- ↑ Paul Gilster, Digital Literacy, New York: Wiley and Computer Publishing, 1997, p.1.

- ↑ Barbara R. Jones-Kavalier and Suzanne L. Flannigan: Connecting the Digital Dots: Literacy of the 21st Century

- ↑ Horrigan, J. B. 2009. "Home Broadband Adoption." Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ↑ Smith, A., K. Zickuhr. 2012. "Digital Differences." Pew Internet & American Life Project.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 70.2 Stephanie Vie, Digital Divide 2.0: “Generation M” and Online Social Networking Sites in the Composition Classroom, Computers and Composition, Volume 25, Issue 1, 2008, Pages 9-23, ISSN 8755-4615, 10.1016/j.compcom.2007.09.004. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S8755461507000989>

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Janet Martorana, Sylvia Curtis, Sherry DeDecker, Sylvelin Edgerton, Carol Gibbens, Lorna Lueck, Bridging the gap: Information literacy workshops for high school teachers, Research Strategies, Volume 18, Issue 2, 2nd Quarter 2001, Pages 113-120, ISSN 0734-3310, 10.1016/S0734-3310(02)00067-8. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0734331002000678>

- ↑ Erickson, P.M., Fox, W. S., & Stewart, D. (Eds.). (2010). National Standards for Teachers of Family and Consumer Sciences: Research, implementation, and resources. Published electronically by the National Association of Teacher Educators for Family and Consumer Sciences. Available at <http://www.natefacs.org/JFCSE/Standards_eBook/Standards_eBook.pdf>

- ↑ Irene Clark, Information literacy and the writing center, Computers and Composition, Volume 12, Issue 2, 1995, Pages 203-209, ISSN 8755-4615, 10.1016/8755-4615(95)90008-X. (http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/875546159590008X)

- ↑ Karvalics, L. Z. (2007), 'Information Society - what is it exactly? (The meaning, history and conceptual framework of an expression)', in Pinter, R. (ed) 'Information Society: From Theory to Political Practice', network for Teaching Information Society: Budapest.

- ↑ 75.0 75.1 United States of America. Executive Office of the President. Office of Management and Budget's E-Government Task Force. Implementing the President's Management Agenda for E-Government. By Mark Forman. 27 Feb. 2002. E-Government Task Force.<www.usa.gov/Topics/Includes/Reference/egov_strategy.pdf>

- ↑ The U.S. National Archives and Records Administration. "E-Government Act of 2002." National Archives and Records Administration.<http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/PLAW-107publ347/pdf/PLAW-107publ347.pdf>

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Chen, Y. N., Chen, H. M., Huang, W., Ching, R. K. H. "E-Government Strategies in Developed and Developing Countries: An Implementation Framework and Case Study". Journal of Global Information Management. 14(1). 23-46. January–March 2006.

- ↑ Federal Communications Commission. "Federal Communications Commission Strategic Goals - Broadband." Federal Communications Commission (FCC) Home Page. 2009. <http://www.fcc.gov/broadband/>.

- ↑ Digital Government: Building a 21st Century Platform to Better Serve The American People, May 23, 2012.<http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/egov/digital-government/digital-government-strategy.pdf>

- ↑ White, D. Steven and Ariguzo, Godwin, A Time-Series Analysis of U.S. E-Commerce Sales (October 17, 2011). Review of Business Research, Vol. 11, No. 4, pp. 134-140, 2011. Available at SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=1940960

- ↑ Putnam RD. 2000. Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York: Simon & Schuster

- ↑ Kraut R., M. Patterson, V. Lundmark, S. Kiesler, T. Mukophadhyay, and W. Scherlis. 1998. "Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychology 53:1011-1031.

- ↑ Gibson RK, PEN Howard, S. Ward. 2000. "Social capital, Internet connectedness, and political participation: A four-country study. Pappres. 2000 International Political Science Association Meeting Quebec, Canada.

- ↑ 84.0 84.1 84.2 84.3 84.4 du Rausas, Mattheiu Pelissie, James Manyika, Eric Hazan, Jacques Bughin, Michael Chui, and Remi Said. 2011. "Internet matters: The Net's sweeping impact on growth, jobs, and prosperity." McKinsey Global Institute. Retrieved from: http://www.mckinsey.com/Insights/MGI/Research/Technology_and_Innovation/Internet_matters

- ↑ NetImpact. 2002. Study overview and key findings. Retrieved July 30, 2004 from http://www.netimpactusdy.com/nis_2002.html.

- ↑ Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development. 2008. "The Future of the Internet Economy." OECD Ministerial Meeting on the Future of the Internet Economy. Retrieved from: http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/20/41/40789235.pdf

- ↑ Environmental News Network Staff. 2000. "Internet boosts economy and saves energy, report says. CNN. Retrieved from: http://articles.cnn.com/2000-01-20/nature/internet.energy.enn_1_energy-costs-internet-economy-joseph-romm?_s=PM:NATURE

- ↑ Nussbaum, Martha. 2011. "Creating Capabilities: The Human Development Approach." Cambridge, MA: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- ↑ Sen, Amartya. 1999. Development as Freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Reilley, Collen A. "Teaching Wikipedia as a Mirrored Technology." First Monday, Vol. 16, No. 1-3, January 2011

- ↑ Correa, Teresa. (2008) "Literature Review: Understanding the "second-level digital divide" papers by Teresa Correa. Unpublished manuscript, School of Journalism, College of Communication, University of Texas at Austin. .

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 . Schradie, Jen. "The Digital Production Gap: The Digital Divide and Web 2.0 Collide." Poetics, Vol. 39, No. 2. April 2011, p. 145-168.

- ↑ Reinhart, J., Thomas, E., and Toriskie, J. (2011). K-12 Teachers: Technology Use and the Second Level Digital Divide. Journal Of Instructional Psychology, 38(3/4), 181.

- ↑ Reinhart, J., Thomas, E., and Toriskie, J. (2011). K-12 Teachers: Technology Use and the Second Level Digital Divide. Journal Of Instructional Psychology, 38(3/4), 181.

- ↑ Information Society Commission, 2002; UNESCO, 2005

- ↑ Enrico Ferro, Natalie C. Helbig, J. Ramon Gil-Garcia, The role of IT literacy in defining digital divide policy needs, Government Information Quarterly, Volume 28, Issue 1, January 2011, Pages 3-10, ISSN 0740-624X, 10.1016/j.giq.2010.05.007. <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0740624X10000997>