Dielheim

| Dielheim | ||

|---|---|---|

| ||

| ||

Dielheim | ||

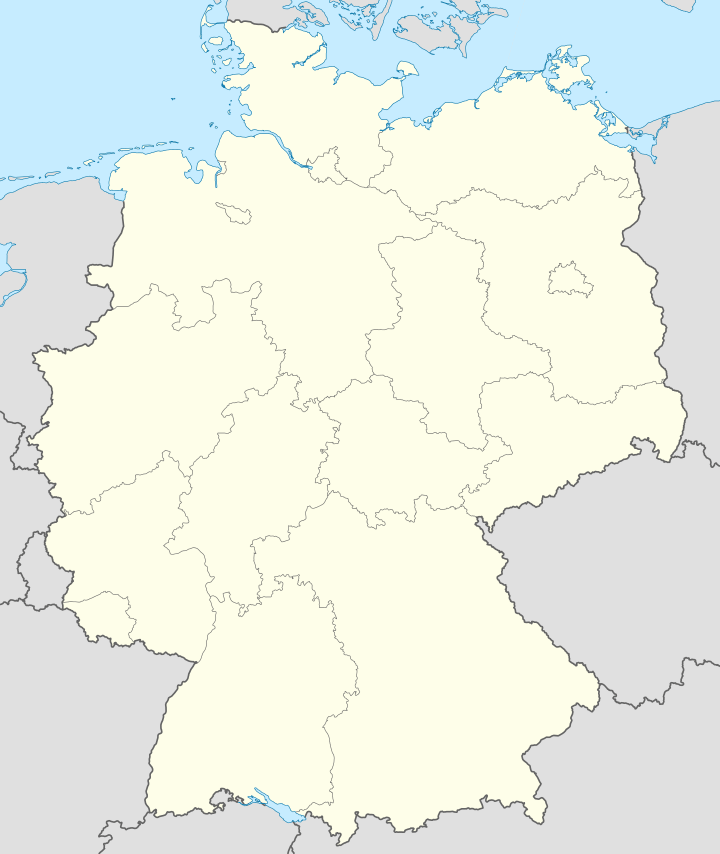

Location of Dielheim within Rhein-Neckar-Kreis district

| ||

| Coordinates: 49°16′57″N 08°44′05″E / 49.28250°N 8.73472°ECoordinates: 49°16′57″N 08°44′05″E / 49.28250°N 8.73472°E | ||

| Country | Germany | |

| State | Baden-Württemberg | |

| Admin. region | Karlsruhe | |

| District | Rhein-Neckar-Kreis | |

| Government | ||

| • Mayor | Hans-Dieter Weis | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 22.67 km2 (8.75 sq mi) | |

| Population (2012-12-31)[1] | ||

| • Total | 8,831 | |

| • Density | 390/km2 (1,000/sq mi) | |

| Time zone | CET/CEST (UTC+1/+2) | |

| Postal codes | 69234 | |

| Dialling codes | 06222 | |

| Vehicle registration | HD | |

| Website | www.dielheim.de | |

Dielheim is a municipality in the Rhein-Neckar district of Baden-Württemberg, Germany.

Geography

Location

Dielheim lies on the western edge of the Kraichgau and the upper Rhine valley. The Leimbach flows East to West through the center of Dielheim and its boroughs Horrenberg and Balzfeld. The Leimbach rises in Balzfeld.

Boroughs

Dielheim includes the following boroughs in order of the number of residents:

- Dielheim

- Horrenberg

- Balzfeld

- Unterhof

- Oberhof

Neighboring communities

Clockwise from the north around Dielheim are the following communities:

- Mauer

- Meckesheim

- Sinsheim

- Mühlhausen

- Rauenberg

- Wiesloch

The nearest cities are:

- Wiesloch 4 km

- Sinsheim 15 km

- Heidelberg 20 km

History

Dielheim

Dielheim was first mentioned in the Lorsch codex in 767. Next to Diedelsheim and Schluchtern, Dielheim is one of the three oldest communities in the Kraichgau. The area was settled by the Romans, so one can assume the village was founded in the 6th century. The name used in the Lorsch Codex, diuuelenheim, may be the result of a reading or writing error made in the 12th century. The letters u and v were often confused, so one can assume the name was divvelenheim. The geminate vv stands for w, which was not commonly used at that time. Therefore we theorize that the name has an origin in the name of a Frankish founder named Diwelo. After going through many changes, the spelling we see today, Dielheim, first appears in the 17th century. The rulers of town can first be identified after late in the 13th century.

By 1272 the prince-bishops of Speyer had won half of Dielheim. Prince-bishop Adolf, who was in desperate need of money, pawned his half of Dielheim to Conz Mönch of Rosenberg in 1380. Conz Mönch took the other half of the village in the following years, thereby putting Dielheim in the possession of a noble for the first time. Conz Mönch, to ensure his control of the area, had a simple castle built on the Teufelskopf. This castle was probably more like a fortified farm than a proper castle. The isolated fortification could not be maintained for long and was quickly described as abandoned. Less than 200 years later, the castle appears as a place name. After multiple changes in ownership and having been pawned many times (noble families documented in this period include von Sickingen, von Rosenberg, von Menzingen, von Neipberg, von Gemmingen as well as the prince-bishops of Speyer), Dielheim finally came as a whole into the ownership of the prince-bishops of Speyer in 1512. The administrative seat of Dielheim for the prince-bishop was in Rotenberg. In the German Peasants' War in 1525, many farmers from Dielheim fought on the side of the so-called Mob of Malsch (Malscher Haufens) against the oppression of the rule of the prince-bishops. After the defeat of the revolt, the village had to suffer harsh penalties. In the Thirty Years' War, Dielheim was almost completely destroyed by the troops of the Electorate of the Palatinate of the Rhine, the Holy Roman Empire, and Sweden. The region recovered only slowly from the loss of people and buildings.

Hardly had the essentials of the village been rebuilt when the War of the Palatinian Succession (a.k.a. War of the Grand Alliance) broke out. In 1689 the French general Mélac reduced Dielheim to ashes. For this reason no building from the time of this catastrophe remains today. From the middle of the 18th century the population of the region boomed. The overpopulation of the region led to property being split into ever smaller pieces due to inheritance. The fields were divided into ever smaller plots that could no longer support or feed the people on the land. Hundreds attempted to find their fortune by emigrating to Hungary, Russia, Romania, Serbia, Algeria, South America, Switzerland, and above all, the United States of America. In the end, emigration was not enough to ensure that everyone remaining in Dielheim had work and enough to eat.

The tobacco industry took advantage of this situation in 1850. The oversupply of labor and the low cost of that labor in the rural parts of Baden helped the cigar industry to boom. For about 100 years many people of Dielham made their living in the numerous cigar factories of the village, after which the tobacco industry went into rapid decline. From about 800 jobs suddenly only 10 remained.

Workers had to reorient themselves and take on new unfamiliar jobs. This changed Dielheim in the 1950s and 1960a to a commuter town. Only the creation of Dielheim's industrial and commercial district led to the creation of its own companies, so that workers could once again find jobs in town. Today's Dielheim is known as a wine-growing region with 77 hectares of surrounding grape fields. Dielheimer Teufelskopf is known by wine lovers throughout Germany. In 1972 Horrenberg joined the municipality of Dielheim.

Horrenberg

Horrenberg lies on a road between Speyer, Bad Wimpfen, and Nuremberg that has been in use since Roman times. This road, named an imperial highway (Reichstrasse) in 1433, was one of the most important thoroughfares in Germany up until the late Middle Ages. In medieval documents, the road is often referred to as the Kaiserstraße, the emperor's highway, because over the centuries many high ranking personalities used the imperial highway. The Roman general Julian (359), the king of the Huns Attila (451), king Conrad III (1150), king Philipp of Swabia (1199), emperor Frederick II (1205), and king Henry VII (1224) all sojourned past the place where Horrenberg stands today. A valuable glass fragment from the 11th or 12th century found at castle Horrenberg indicates the passing of royal parties. This kind of purple-red and white glass has otherwise only been found at St. Denis in Paris, in Italian Pavia, and in Birka near Stockholm.

Around the year 1220, the then reigning lord of the region erected a fortified tower in order to protect the imperial highway at the toll station in Horrenberg. For the location of the fort, they chose a hill next to the highway which loomed a swampy low-lying section of the Leimbach. Horrenberg comes from HOR- swamp or mud and BERG mountain or hill. Around the castle a small village developed over time. The first noble recorded in association with Horrenberg is Dieter von Horrenberg in 1238. He was most likely named after the new castle. Before 1272, bishop Henry of Speyer took over the upper Bruhrain to which the village Horrenberg and castle belonged. This purchase related document is the first definitive mention of Horrenberg. Older documents cannot be fully relied upon because of the similar way Castle Hornberg on the Neckar was written at that time. In 1366 emperor Charles IV confirmed the right of bishop Lamprecht of Speyer to collect the toll income of Horrenberg.

By the middle of the 15th century the minor noble family of Horrenberg had died out. The prince-bishop of Speyer had to relinquish the authority of Rotenberg, to which Horrenberg belonged, to the Palatinate of the Rhine from 1462 to 1498. At this time the Horrenberg fell into ruin as the lords of the Horrenberg had no need of the castle and left the community to fend for itself. In the sources of the 15th and 16th century continuously refer to the former castle.

During the Thirty Years' War, Horrenberg suffered the same fate as the surrounding villages. From 1618 to 1648 the village was plundered again and again by the imperial, palatine, Swedish, Bavarian, and French troops. By the end of the war, only three families still lived in Horrenberg. All houses were destroyed. 20 years after the Thirty Years' War, there were 12 inhabited homes. However, the village never regained the importance it had before the war. The toll station was never rebuilt. The important sheep farms and the great Hubhof of the prince-bishop only served a role as rentable goods. Only in the late 18th century had the number of residents increased to the point where the arable land available was no longer sufficient. Many young people and whole families emigrated overseas. The tobacco industry in contrast to the other communities in the area were very late in erecting cigar factories in the community Horrenberg-Balzfeld.

In 1932 Oberhof and Unterhof were incorporated into Horrenberg. After WW II the population of Horrenberg soared due to the influx of refugees. Today the once tiny village has been replaced with a modern residential community. In the center of the village, the former city hall (built in 1845) still dominates the character of the village. Since Horrenberg-Balzfeld was incorporated in Dielheim in 1972, the city hall has lost its original function. The castle hill, which is accessible again, shows little sign that it once hosted a castle. Today it serves as a place of recreation and vantage point.

Balzfeld

Since the Middle Ages, Balzfeld has belonged politically to it much younger neighbor, Horrenberg. Balzfeld was supposedly founded around the year 1000. A group of hill graves from the early stone age (around 2000 BC) indicates the early settlement of the fruitful hills of Kraichgau. In the year 1306 Balzfeld was first documented as Balgesuelt (balg = hollow or ditch). At this time, the village had already lost its political independence to Horrenberg. At the same time, Horrenberg was always indicated as belonging to Balzfeld in the church hierarchy. "The city hall is in Horrenberg and the church in Balzfeld," appears again and again in records and documents. In 1559 both villages were expressly unified as a single community by the decree of the local ruler after fighting between the residents. Ownership was handled completely differently in free Balzfeld compared with castle village Horrenberg ruled by nobility. The burghers of Balzfeld owned their own fields and had enough access to commons, fields, and forest, unlike the residents of Horrenberg. The Horrenberger farmers owed fealty to their lords and had little land of their own. They were tenants to their lord.

The Thirty Years' War reduced the population of Balzfeld to 3 families. Thanks to its location off the imperial highway, the village did not remain largely undisturbed compared to the neighboring villages. The impractical access meant that Balzfeld fell behind in development compared to Horrenberg since the Thirty Years' War. Not just because of this, there have been seven unsuccessful attempts between 1705 and 1966 to grant the people of Balzfeld political independence from Horrenberg. In the old core of the village stands the 14th century Holy Cross (Heilig Kreuz) church. In contrast to Dielheim and Horrenberg, Balzfeld has been able to maintain its old character in the core of the village. Through recent village renovation measures Balzfeld has tried to profit from this.

Unterhof

Unterhof like Oberhof was originally founded as a feudal settlement for a local lord. Possibly this is the hamlet mentioned under around the year 860 together with Dielheim in the Lorsch codex named Hiltibrandeshusen. In 1341 Unterhof was named for the first time in documents inferiori curia (lesser or lower farm) in rent books of the Speyer office of Rotenberg. In 1401 under the name zum Nydernhofe is the first appearance of the name in the German language. For centuries the prince-bishops of Speyer limited the number of farms to three. During the Thirty Years' War the residents fled their farms and Unterhof lay deserted and overgrown for decades. After resettlement, Unterhof and Oberhof, as tenant farms of the local lords, were occasionally self-administrated. First since 1932 after a drawn out fight for their independence, the settlements belong to Horrenberg. In recent years, Unterhof has transformed itself into a residential community that is still strongly influenced by agriculture.

Oberhof

Oberhof, as the smallest village in the municipality of Dielheim, has preserved its traditional look the best. The village was first mentioned in documents in 1341 as superiore curia (upper or superior farm). The village has retained its larger size over Unterhof into the 20th century. Because of the larger area and better soil, the prince-bishops of Speyer allowed the construction of 5 inheritable farms. Already in 1401 the tenant farms of Oberhof were considered well off. Since the end of the 19th century, the poor transportation connections to Oberhof began to have a negative effect. The number of residents sank continuously in contrast to the other villages. Today the village attempts to preserve its well preserved facade as much as possible.

Government

Municipal council

| Municipal Council 2004 | |||||

| Party | Votes | Seats | |||

| CDU | 62.9% | 14 | |||

| SPD | 17.8% | 3 | |||

| Women for the Community (Bürgerinnen für die Gemeinde) | 12.7% | 2 | |||

| Green | 6.6% | 1 | |||

| Voter Participation: 59,0% | |||||

Coat of arms

The coat of arms was put together from the old coat of arms of Dielheim and Horrenberg. Both included the silver cross on a field of blue from the Prince-bishoprics of Speyer.

The flag is white and blue and together with the coat of arms was awarded by the Rhein-Neckar district administration office in 1985.

Sister cities

St. Nicolas-de-Port, France, May 1985

St. Nicolas-de-Port, France, May 1985 Lengyeltóti, Hungary, June 1994

Lengyeltóti, Hungary, June 1994

References

- ↑ "Gemeinden in Deutschland mit Bevölkerung am 31.12.2012 (Einwohnerzahlen auf Grundlage des Zensus 2011)". Statistisches Bundesamt (in German). 12 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dielheim. |