Dharmaditya Dharmacharya

| Dharmaditya Dharmacharya | |

|---|---|

|

Dharmaditya Dharmacharya in ca. 1930 | |

| Born |

Jagat Man Vaidya 1902 Chikan Bahi, Lalitpur |

| Died | 1963 |

| Occupation | Author, Buddhist scholar and language activist |

| Language | Nepal Bhasa |

| Nationality | Nepalese |

| Ethnicity | Newa |

| Literary movement | Nepal Bhasa renaissance |

Dharmaditya Dharmacharya (Devanagari: धर्मादित्य धर्माचार्य) (born Jagat Man Vaidya) (1902–1963) was a Nepalese author, Buddhist scholar and language activist. He worked to develop Nepal Bhasa and revive Theravada Buddhism when Nepal was ruled by the Rana dynasty and both were dangerous activities, and was consequently jailed.[1][2]

Dharmacharya campaigned for Nepal Era as the national calendar. He also wrote and published the first magazine in Nepal Bhasa and was a major influence in the Nepal Bhasa renaissance.[3] [4] Because of his service to the language, he has also been called the "fifth pillar" of Nepal Bhasa along with the Four Pillars of Nepal Bhasa.

Early life

Dharmacharya was born at Chikan Bahi, Lalitpur District to father Vaidya Vrishman Vandya and mother Muni Thakun Vandya. He studied at Durbar High School in Kathmandu and did his matriculation from Kolkata and enrolled at the University of Calcutta for higher studies.

Buddhist activist

On his visits to Kathmandu during the holidays, he organized Buddhist programs and exhibitions of religious pictures he had collected in Kolkata. In 1924, he established the Buddha Dharma Support Association at the home of Dharma Man Tuladhar. He encouraged its members to read Buddhist books and translated articles in English and Pali into Nepal Bhasa.

Upon his return to Kolkata, he established the Nepalese Buddhist Association to help Nepalese traders who had fallen into difficulty besides teaching them Buddhist principles. In 1928, he helped organize the All India Buddhist Conference.[5]

In an effort to promote Buddhism among the Nepalese in Darjeeling, he brought out Himalaya Bauddha in the Nepali language and Buddhist India in English in 1927 which he and B. M. Barua (Benimadhab Barua) edited.[6][7]

Language activist

Dharmacharya was a cultural nationalist and dedicated himself to promoting Nepal Bhasa and obtaining international recognition for it.[8]

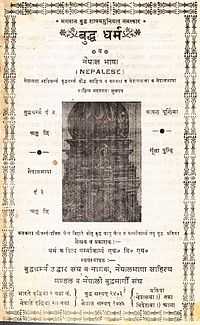

In 1925, he published Buddha Dharma wa Nepal Bhasa (बुद्ध धर्म व नॆपाल भाषा "Buddhism and Nepalese") from Kolkata, India. It was the first ever magazine to be published in Nepal Bhasa.[9] It contained articles on Buddhism and also provided writers in Nepal a place to publish their compositions which they couldn't do at home because of the government's dislike of the language.[10]

In order to support the emerging Nepal Bhasa movement in Nepal and promote the language at home and abroad, he established the first Nepal Bhasa literary organization Nepal Bhasa Sahitya Mandal ("Nepal Bhasa Literature Organization") in Kolkata in 1926.[11]

Dharmacharya returned to Kathmandu with a Master's degree in Pali. He joined the Industry Council as an administrative officer and got married to Asta Maya and settled down into the life of a householder.

Imprisonment

In 1940, Dharmacharya was arrested in a crackdown against democracy activists, writers and social reformers. He was jailed for three months with other Nepal Bhasa writers. Following the incident, he remained inactive in social work for more than five years. He spent the later part of his life lecturing and writing.[12]

Legacy

In 1956, Dharmacharya was decorated with the title of Patron of the Language by Chwasa Pasa.[13] A statue of Dharmacharya has been erected at Pulchok, Lalipur.

References

- ↑ Singh, Harischandra Lal (1996). Reflections on Buddhism of the Kathmandu Valley. Kathmandu: Educational Enterprise. Pages 5-7.

- ↑ Dietrich, Angela (1996). "Buddhist Monks and Rana Rulers: A History of Persecution". Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- ↑ Murti, Ven. PaĪĪā (2005). "A Historical Study of Pariyatti Sikkhâ in Nepal" (PDF). Bangkok, Thailand: Mahachulalongkornrajavidyalaya University. Retrieved 30 June 2011. Pages 15-16.

- ↑ Bajracharya, Phanindra Ratna (2003). Who's Who in Nepal Bhasha. Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Academy. Page 36.

- ↑ "From Editorial Desk". Buddhist Himalaya: A Journal of Nagarjuna Institute of Exact Methods. 1997. Retrieved 7 February 2012.

- ↑ Hridaya, Chittadhar (1982, third ed.) Jheegu Sahitya ("Our Literature"). Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 172.

- ↑ Sen, Jahar and Indian Institute of Advanced Study (1992). India and Nepal: Some aspects of culture contact. Indian Institute of Advanced Study. ISBN 81-85182-69-8, ISBN 978-81-85182-69-8. Page 98.

- ↑ Lecomte-Tilouine, Marie and Dollfus, Pascale (2003) Ethnic Revival and Religious Turmoil: Identities and Representations in the Himalayas. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-565592-3, ISBN 978-0-19-565592-6. Page 100. Retrieved 3 February 2012.

- ↑ LeVine, Sarah and Gellner, David N. (2005) Rebuilding Buddhism: The Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01908-9. Pages 27-28. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- ↑ Lienhard, Siegfried (1992). Songs of Nepal: An Anthology of Nevar Folksongs and Hymns. New Delhi: Motilal Banarsidas. ISBN 81-208-0963-7. Page 4.

- ↑ Shrestha, Bal Gopal (January 1999). "The Newars: The Indigenous Population of the Kathmandu Valley in the Modern State of Nepal)" (PDF). CNAS Journal. Retrieved 23 March 2012. Page 89.

- ↑ LeVine, Sarah and Gellner, David N. (2005) Rebuilding Buddhism: The Theravada Movement in Twentieth-Century Nepal. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01908-9. Page 29. Retrieved 30 June 2013.

- ↑ Hridaya, Chittadhar (1982, third ed.) Jheegu Sahitya ("Our Literature"). Kathmandu: Nepal Bhasa Parisad. Page 192.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||