Detroit

| Detroit, Michigan | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Detroit | |||

|

From top to bottom, left to right: Downtown Detroit skyline and the Detroit River, Fox Theatre, Dorothy H. Turkel House in Palmer Woods, Belle Isle Conservatory, The Spirit of Detroit, Fisher Building, Eastern Market, Old Main at Wayne State University, Ambassador Bridge, and the Detroit Institute of Arts | |||

| |||

| Etymology: French: détroit (strait) | |||

| Nickname(s): The Motor City, Motown, Renaissance City, City of the Straits, The D, Hockeytown, The Automotive Capital of the World, Rock City, The 313 | |||

|

Motto: Speramus Meliora; Resurget Cineribus (Latin: We Hope For Better Things; It Shall Rise From the Ashes) | |||

Location in Wayne County and the state of Michigan | |||

Detroit, Michigan Location in the contiguous United States | |||

| Coordinates: 42°19′53″N 83°02′45″W / 42.33139°N 83.04583°WCoordinates: 42°19′53″N 83°02′45″W / 42.33139°N 83.04583°W[1] | |||

| Country | United States of America | ||

| State | Michigan | ||

| County | Wayne | ||

| Founded | 1701 | ||

| Incorporated | 1806 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor–Council | ||

| • Body | Detroit City Council | ||

| • Mayor | Mike Duggan (D) | ||

| • City Council |

Members

| ||

| Area[2] | |||

| • City | 142.87 sq mi (370.03 km2) | ||

| • Land | 138.75 sq mi (359.36 km2) | ||

| • Water | 4.12 sq mi (10.67 km2) | ||

| • Urban | 1,295 sq mi (3,350 km2) | ||

| • Metro | 3,913 sq mi (10,130 km2) | ||

| Elevation[1] | 600 ft (200 m) | ||

| Population (2013)[3][4] | |||

| • City | 688,701 [5] | ||

| • Rank | US: 18th | ||

| • Density | 5,142/sq mi (1,985/km2) | ||

| • Urban | 3,734,090 (US: 11th) | ||

| • Metro | 4,292,060 (US: 14th) | ||

| • CSA | 5,311,449 (US: 12th) | ||

| Demonym | Detroiter | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC−5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC−4) | ||

| Area code(s) | 313 | ||

| FIPS code | 26-22000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1617959[1] | ||

| Website | DetroitMI.gov | ||

Detroit (/dɨˈtrɔɪt/[6]) is the most populous city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the largest city on the United States–Canada border. It is the seat of Wayne County, the most populous county in the state. It is a primary business, cultural, financial and transportation center in the Metro Detroit area, a region of 5.3 million people. It is a major port on the Detroit River, a strait that connects the Great Lakes system to the Saint Lawrence Seaway. It was founded on July 24, 1701, by the French explorer and adventurer Antoine Laumet de La Mothe, sieur de Cadillac and a party of settlers.

The Detroit area emerged as a significant metropolitan region within the United States in the early 20th century, and this trend only hastened in the 1950s and 1960s, with the construction of a regional freeway system. Detroit is the center of a three-county Urban Area (population 3,734,090, area of 1,337 square miles (3,460 km2), a 2010 United States Census) six-county Metropolitan Statistical Area (2010 Census population of 4,296,250, area of 3,913 square miles [10,130 km2]), and a nine-county Combined Statistical Area (2010 Census population of 5,218,852, area of 5,814 square miles [15,060 km2]).[4][7][8] The Detroit–Windsor area, a commercial link straddling the Canada–U.S. border, has a total population of about 5,700,000.[9] The Detroit metropolitan region holds roughly one-half of Michigan's population.[3][8]

Known as the world's automotive center,[10] "Detroit" is a metonym for the American automobile industry.[11] Detroit's auto industry was an important element of the American "Arsenal of Democracy" supporting the Allied powers during World War II.[12] It is an important source of popular music legacies celebrated by the city's two familiar nicknames, the Motor City and Motown.[13] Other nicknames arose in the 20th century, including City of Champions, beginning in the 1930s for its successes in individual and team sport;[14] The D; Hockeytown (a trademark owned by the city's NHL club, the Red Wings); Rock City (after the Kiss song "Detroit Rock City"); and The 313 (its telephone area code).[15][16]

Between 2000 and 2010 the city's population fell by 25 percent, changing its ranking from the nation's 10th-largest city to 18th.[17] In 2010, the city had a population of 713,777, more than a 60 percent drop from a peak population of over 1.8 million at the 1950 census. This resulted from suburbanization, industrial restructuring and the decline of Detroit's economic strength.[3] Following the shift of population and jobs to its suburbs or other states or nations, the city focused on reestablishing itself as the metropolitan region's employment and economic center. Downtown Detroit has held an increased role as an entertainment destination in the 21st century, with the restoration of several historic theatres, several new sports stadiums, three new stadiums, and a riverfront revitalization project. More recently, the population of Downtown Detroit, Midtown Detroit, and a handful of other neighborhoods has increased. Many other neighborhoods remain distressed and even heavily abandoned.

The Governor of Michigan, Rick Snyder, declared a financial emergency for the city in March 2013, appointing an emergency manager. On July 18, 2013, Detroit filed the largest municipal bankruptcy case in U.S. history.[18] It was declared bankrupt by Judge Steven W. Rhodes of the Bankruptcy Court for the Eastern District of Michigan on December 3, 2013; he cited its $18.5 billion debt and declared that negotiations with its thousands of creditors were unfeasible.[19] On November 7, 2014, Judge Rhodes approved the city's bankruptcy plan, allowing the city to begin the process of exiting bankruptcy.[20] The City of Detroit successfully left Chapter 9 municipal bankruptcy with all finances handed back to Detroit beginning at midnight on December 11, 2014.[21][22][23]

History

European settlement

The city was named by French colonists, referring to the Detroit River (French: le détroit du lac Érié, meaning the strait of Lake Erie), linking Lake Huron and Lake Erie; in the historical context, the strait included the St. Clair River, Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River.[24][25]

On the shores of the strait, in 1701, the French officer Antoine de La Mothe Cadillac, along with fifty-one French people and French-Canadians, founded a settlement called Fort Pontchartrain du Détroit, naming it after the comte de Pontchartrain, Minister of Marine under Louis XIV.[26] France offered free land to colonists to attract families to Detroit; when it reached a total population of 800 in 1765, it was the largest city between Montreal and New Orleans, both French settlements.[27] By 1773, the population of Detroit was 1,400. By 1778, its population was up to 2,144 and it was the third-largest city in the Province of Quebec.[28]

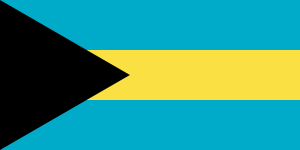

The region's fur trade was an important economic activity. Detroit's city flag reflects its French heritage. (See Flag of Detroit, Michigan).

During the French and Indian War (1754-1763), the North American front of the Seven Years' War between Britain and France, British troops gained control of the settlement in 1760. They shortened the name to Detroit. Several Native American tribes launched Pontiac's Rebellion (1763), and conducted a siege of Fort Detroit, but failed to capture it. France ceded its territory in North America east of the Mississippi to Britain following the war.

Following the American Revolutionary War, Britain ceded Detroit along with other territory in the area to the United States under the Jay Treaty (1796), which established the northern border with Canada.[30] In 1805, fire destroyed most of the settlement, which consisted mostly of wooden buildings. A river warehouse and brick chimneys of the former wooden homes were the sole structures to survive.[31]

19th century

From 1805 to 1847, Detroit was the capital of Michigan. Detroit surrendered without a fight to British troops during the War of 1812 in the Siege of Detroit. The Battle of Frenchtown (January 18–23, 1813) was part of a United States effort to retake the city, and American troops suffered their highest fatalities of any battle in the war. This battle is commemorated at River Raisin National Battlefield Park south of Detroit in Monroe County. Detroit was finally recaptured by the United States later that year.

It was incorporated as a city in 1815.[29] As the city expanded, a geometric street plan developed by Augustus B. Woodward was followed, featuring grand boulevards as in Paris.

Prior to the American Civil War, the city's access to the Canadian border made it a key stop for refugee slaves gaining freedom in the North along the Underground Railroad. Many went across the Detroit River to Canada to escape pursuit by slave catchers.[29] There were estimated to be 20,000 to 30,000 African-American refugees who settled in Canada.

Numerous men from Detroit volunteered to fight for the Union during the American Civil War, including the 24th Michigan Infantry Regiment (part of the legendary Iron Brigade), which fought with distinction and suffered 82% casualties at the Battle of Gettysburg in 1863. When the First Volunteer Infantry Regiment arrived to fortify Washington, DC, President Abraham Lincoln is quoted as saying "Thank God for Michigan!" George Armstrong Custer led the Michigan Brigade during the Civil War and called them the "Wolverines".[32]

During the late 19th century, several Gilded Age mansions reflecting the wealth of industry and shipping magnates were built east and west of the current downtown, along the major avenues of the Woodward plan. Most notable among them was the David Whitney House located at 4421 Woodward Avenue, which became a prime location for mansions. During this period some referred to Detroit as the Paris of the West for its architecture, grand avenues in the Paris style, and for Washington Boulevard, recently electrified by Thomas Edison.[29] The city had grown steadily from the 1830s with the rise of shipping, shipbuilding, and manufacturing industries. Strategically located along the Great Lakes waterway, Detroit emerged as a major port and transportation hub.

In 1896, a thriving carriage trade prompted Henry Ford to build his first automobile in a rented workshop on Mack Avenue. During this growth period, Detroit expanded its borders by annexing all or part of several surrounding villages and townships.

20th century

In 1903, Henry Ford founded the Ford Motor Company. Ford's manufacturing—and those of automotive pioneers William C. Durant, the Dodge brothers, Packard, and Walter Chrysler—established Detroit's status in the early 20th century as the world's automotive capital. The proliferation of businesses created a synergy that also encouraged truck manufacturers such as Rapid and Grabowsky.[29] The growth of the auto industry was reflected by changes in businesses throughout the Midwest and nation, with the development of garages to service vehicles and gas stations, as well as factories for parts and tires.

With the rapid growth of industrial workers in the auto factories, labor unions such as the American Federation of Labor and the United Auto Workers fought to organize workers to gain them better working conditions and wages. They initiated strikes and other tactics in support of improvements such as the 8-hour day/40-hour work week, healthcare benefits, pensions, increased wages and improved working conditions. The labor activism during those years increased influence of union leaders in the city such as Jimmy Hoffa of the Teamsters and Walter Reuther of the Autoworkers.

The prohibition of alcohol from 1920 to 1933 resulted in the Detroit River becoming a major conduit for smuggling of illegal Canadian spirits, organized in large part by the notorious Purple Gang, dominated by Jewish immigrants. There was also extensive smuggling across the St. Clair River north of the city.[33]

Detroit, like many places in the United States, developed racial conflict and discrimination in the 20th century following rapid demographic changes as hundreds of thousands of new workers were attracted to the industrial city; in a short period it became the 4th-largest city in the nation. The Great Migration brought rural blacks from the South; whites also migrated to the city; and immigration brought southern and eastern Europeans; both competed with native whites for jobs and housing in the booming city. Detroit was one of the major Midwest cities that was a site for the dramatic urban revival of the Ku Klux Klan beginning in 1915. "By the 1920s the city had become a stronghold of the KKK," whose members opposed Catholic and Jewish immigrants, as well as black Americans.[34] Strained racial relations were evident at the 1925 trial of Dr. Ossian Sweet, an African-American Detroit physician, his wife, and other family members who were acquitted of murder. They had defended themselves when a white mob gathered to try to force him and his family out of a predominantly white neighborhood.[35] The Black Legion also was active in the Detroit area.

In the 1940s the world's "first urban depressed freeway" ever built, the Davison,[36] was constructed in Detroit. During World War II, the government encouraged retooling of the American automobile industry in support of the Allied powers, leading to Detroit's key role in the American Arsenal of Democracy.[37] Six ships of the United States Navy have been named after the city, including USS Detroit (LCS-7).

Social tensions had accompanied the rapid pace of growth and competition among ethnic groups; racism developed among some European immigrants and their descendants who were competing in the working class. On January 20, 1942, with a cross burning nearby (a sign of the KKK, but this organization had declined markedly since 1925), 1,200 whites tried to prevent black families from moving into a new housing development in an all-white area of the city. In June 1943, Packard promoted three blacks to work next to whites on its assembly lines. In response, 25,000 whites walked off the job, effectively slowing down critical war production. During the protest, a voice with a southern accent shouted in the loudspeaker, "I'd rather see Hitler and Hirohito win than work next to a nigger."[38] The Detroit Race Riot of 1943 took place three weeks after the Packard plant protest. Over the course of three days, 34 people were killed, of whom 25 were African American, and approximately 600 were injured.[34][39]

Postwar era

Industrial mergers in the 1950s, especially in the automobile sector, increased oligopoly in the American auto industry. Detroit manufacturers such as Packard and Hudson merged into other companies and eventually disappeared.

As in other major American cities in the postwar era, construction of an extensive highway and freeway system around Detroit and pent-up demand for new housing stimulated suburbanization; the GI Bill helped veterans buy new homes and highways made commuting by car easier. In 1956, Detroit's last heavily used electric streetcar line along the length of Woodward Avenue was ripped out and replaced with gas-powered buses. It was the last line of what had once been a 534 miles network of electric streetcars, which had once served outlying cities as well. In 1941 at peak times, a streetcar ran on Woodward Avenue every 60 seconds.[40][41]

All of these changes in the area's transportation system favored low density, auto-oriented development rather than high-density urban development. These were factors that contributed to the metro Detroit area becoming the most sprawling job market in the United States, though other major American cities also developed suburbanization.[42] The expansion of jobs and lack of public transportation put many jobs beyond the reach of lower income workers who remained in the city.

In 1950, before the area shut down its last electric streetcar lines, the city held about one-third of the state's population. Over the next sixty years and related outlying development, the city's population declined to less than 10 percent of the state's population. During the same time period, the sprawling Detroit metropolitan area, which surrounds and includes the city, grew to contain more than half of Michigan's population.[29] Commensurate with the shift of population and jobs to suburbs and other American cities, Detroit's tax base eroded.

In June 1963, Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. gave a major speech in Detroit that foreshadowed his "I Have a Dream" speech in Washington, D.C. two months later. While the African-American Civil Rights Movement gained significant federal civil rights laws in 1964 and 1965, longstanding inequities resulted in confrontations between the police and inner city black youth wanting change, culminating in the Twelfth Street riot in July 1967. Governor George W. Romney ordered the Michigan National Guard into Detroit, and President Johnson sent in U.S. Army troops. The result was 43 dead, 467 injured, over 7,200 arrests, and more than 2,000 buildings destroyed, mostly in black residential and business areas. Thousands of small businesses closed permanently or relocated to safer neighborhoods. The affected district lay in ruins for decades.[43]

On August 18, 1970, the NAACP filed suit against Michigan state officials, including Governor William Milliken, for de facto school segregation. The trial began April 6, 1971, and lasted 41 days. The NAACP argued that although schools were not legally segregated, the city of Detroit and its surrounding counties had enacted policies to maintain racial segregation in public schools. The NAACP also suggested a direct relationship between unfair housing practices (such as redlining of certain neighborhoods) and educational segregation.[44] District Judge Steven J. Roth held all levels of government accountable for the segregation in his ruling on Milliken v. Bradley. The Sixth Circuit Court affirmed some of the decision, withholding judgment on the relationship of housing inequality with education. The court specified that it was the state's responsibility to integrate across the segregated metropolitan area.[45]

The governor and other accused officials appealed the decision to the U.S. Supreme Court, which took up the case February 27, 1974.[44] The subsequent Milliken v. Bradley decision had wide national influence. In a narrow decision, the Court found that schools were a subject of local control and that suburbs could not be forced to solve problems in the city's school district. According to Gary Orfield and Susan E. Eaton in their 1996 book Dismantling Desegregation, the "Supreme Court's failure to examine the housing underpinnings of metropolitan segregation" in Milliken made desegregation "almost impossible" in northern metropolitan areas. "Suburbs were protected from desegregation by the courts ignoring the origin of their racially segregated housing patterns." "Milliken was perhaps the greatest missed opportunity of that period," said Myron Orfield, professor of law and director of the Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity at the University of Minnesota. "Had that gone the other way, it would have opened the door to fixing nearly all of Detroit's current problems."[46] John Mogk, a professor of law and an expert in urban planning at Wayne State University in Detroit, says, "Everybody thinks that it was the riots [in 1967] that caused the white families to leave. Some people were leaving at that time but, really, it was after Milliken that you saw mass flight to the suburbs. If the case had gone the other way, it is likely that Detroit would not have experienced the steep decline in its tax base that has occurred since then."[46]

Supreme Justice William O. Douglas' dissenting opinion in Miliken held that

"there is, so far as the school cases go, no constitutional difference between de facto and de jure segregation. Each school board performs state action for Fourteenth Amendment purposes when it draws the lines that confine it to a given area, when it builds schools at particular sites, or when it allocates students. The creation of the school districts in Metropolitan Detroit either maintained existing segregation or caused additional segregation. Restrictive covenants maintained by state action or inaction build black ghettos ... the task of equity is to provide a unitary system for the affected area where, as here, the State washes its hands of its own creations."[47]

Coleman Young years

In November 1973, the city elected Coleman A. Young as its first black mayor. The election had pitted the then state representative against Detroit Police Department commissioner John Nichols. Nichols had been under fire from the black community over a lack of racial diversity in the department and police brutality by the department's special unit known as STRESS (Stop the Robberies, Enjoy Safe Streets). After taking office, Young disbanded the controversial STRESS unit and prioritized increasing racial diversity in the department.[48]

One of Young's earliest initiatives was trying to improve Detroit's transportation system. In 1976, the federal government offered $600 million for building a regional rapid transit system, under a single regional authority. Suburbanites in public meetings expressed fear over crime and undesirables having access to their communities, and Young felt suburbanites would have too much control over a system in which Detroiters would be the majority of riders.[49] The inability for Detroit and its suburban neighbors to resolve these conflicts would result in the region losing the majority of the funding. Tension with Young and his suburban counterparts over regional matters would be an issue throughout Young's term. Following the failure to reach an agreement over the larger system, Young decided to move forward with construction of the elevated downtown circulator portion of the system that would be become the Detroit People Mover.[50]

The gasoline crises of 1973 and 1979 also affected Detroit and the U.S. auto industry. Smaller more fuel-efficient cars made by foreign makers were increasingly purchased by many consumers as the price of gas rose. Efforts to revive the city were stymied by the struggles of the auto industry, as their sales and market share declined. As a way to cut costs, automakers laid off thousands of employees and closed older, less efficient plants in the city, further eroding the tax base. To counteract this, Mayor Young controversially championed the use of eminent domain to build two large new auto assembly plants in the city: the General Motors Detroit/Hamtramck Assembly Plant, also known as the "Poletown Plant" for its location in a formerly Polish neighborhood, and the Chrysler Jefferson North Assembly Plant.[51]

As mayor, Young sought to revive the city by seeking to increase investment in the city's declining downtown. The Renaissance Center, an office and retail complex conceived by Henry Ford II in 1971 as a way to increase investment in the city, opened in 1977. This group of skyscrapers, designed as a city within a city, was an attempt to keep businesses in downtown that were leaving for newer spaces in the suburbs. The project has been criticized on urban design terms for cutting itself off from the larger city and reducing urban interaction.[29][52][53]

Young also gave city support to other large developments such as Riverfront Condominiums and the Millender Center Apartments, Harbortown, which were built on or near Detroit's waterfront to attract middle and upper-class residents back to the city and develop a 24-hour population downtown. Two new high rise office building were also built: 150 West Jefferson in 1989 and One Detroit Center in 1993. Despite the Renaissance Center and other projects, the downtown area continued to lose businesses to the suburbs. Downtown's last two department stores, Crowley's and Hudson's, shuttered in 1977 and 1983 respectively. Hotels like the Book-Cadillac closed and many large office buildings went vacant. Further, Young faced criticism that he was too focused on downtown development and not doing enough to lower the city's high crime rate and improve city services.

1990's - Present

In 1993 Young retired as Detroit's longest serving mayor, deciding not to seek a sixth term. That year the city elected as mayor Dennis Archer a former Michigan Supreme Court justice. Like Young he saw downtown development as way revive the city. He also sought to ease tensions with Detroit's suburban neighbors. As mayor he pushed for a referendum to allow casino gambling in the city to as a way to draw tourist to the city. Following its passage in 1996, in 1999 MGM Grand Detroit, Motor City Casino and Greektown Casino opened temporary facilities. Permanent casinos that would have hotels were originally planned for the riverfront, but issues over land acquisition led to construction delays and them being relocated to downtown opening in 2007–08.[54]

Archer also supported the construction of two new downtown stadiums for the Detroit Tigers and Detroit Lions that opened in 2000 and 2002, respectively. The opening of the Lions' home stadium relocated them to the city proper for the first time since 1974.

In 1999 Archer announced the redevelopment of Campus Martius, it would reconfigure downtown's main intersection into a new park in the center of downtown. Along with that announcement came another one, that Compuware a software company would relocate its 4,000 workers from suburban Farmington Hills into a new headquarters adjacent to the park. Opening in 2004, the park has been cited by Project for Public Spaces as one of the best public spaces in the United Spaces and the Urban Land Institute as one the top 10 parks that help revive downtowns.[55][56] The creation of Campus Martius Park and the relocation of Compuware has been seen as the catalyst for downtown Detroit the increased amount of investment in the 2000s.[57]

The city hosted the 2005 MLB All-Star Game, 2006 Super Bowl XL, 2006 and 2012 World Series, WrestleMania 23 in 2007, and the NCAA Final Four in April 2009. To prepare for these events, the city undertook many improvements to the downtown area. In 2011, Detroit Medical Center and Henry Ford Health System substantially increased investments in medical research facilities and hospitals in the city's Midtown and New Center.[58][59] The historic Book Cadillac Hotel and the Fort Shelby Hotel were renovated and reopened for business for the first time in 24 years and 34 years respectively.[52]

The city's riverfront has been the focus of redevelopment for renewed engagement with the river, following successful examples of other older industrial cities, including Windsor, Canada, which began its waterfront parkland conversion in the 1990s. In 2001, the first portion (from Joe Louis Arena through Hart Plaza) of the International Riverfront was completed as a part of the city's 300th anniversary celebration. In succeeding years, miles of parks and associated fountains and landscaping were completed. In 2011, the Port Authority Passenger Terminal opened with the river walk connecting Hart Plaza to the Renaissance Center. This development is a mainstay in the city's plan to enhance its economy as a destination for tourism, including visits by suburban residents.[53]

Since 2013, construction activity, particularly rehabilitation of historic central city buildings, has increased markedly. The number of vacant downtown buildings has declined from nearly 50 to only 13, with that number set to decline further with ongoing projects.[60] Among the most notable rehabilitation projects are the David Broderick Tower, now a luxury apartment building, the David Whitney Building, now an Aloft Hotel and luxury apartments, the Garden Theater complex, and rows of historic commercial buildings along Woodward Avenue (called Merchants' Row) and Broadway. Meanwhile, work is underway or set to begin on the historic, abandoned Wurlitzer Building and Strathmore Hotel. In addition, a large vacant parcel separating Midtown and Downtown is currently under construction and will become a new arena for the Detroit Red Wings, with attached residential, hotel, and retail use.[61] The project has become a focal point for the city's increasingly successful historic preservation movement, which is insisting on the rehabilitation of two historic high-rise hotels located near the new arena.[62]

Decline

Long a major population center and major engine of worldwide automobile manufacturing, Detroit has gone through a long economic decline produced by numerous factors.[63][64][65] Like many industrial American cities, Detroit reached its population peak in the 1950 census. The peak population was 1.8 million people. Following suburbanization, industrial restructuring and loss of jobs (as described above), by the 2010 census, the city had less than 40 percent of that number at just over 700,000 residents. The city has declined in population with each subsequent census since 1950.[66][67]

Frank J. Popper, a professor at the Edward J. Bloustein School of Planning and Public Policy of Rutgers University and the Princeton Environmental Institute at Princeton University compares the Great Plains decline with Detroit's. During the 20th century many rural counties have seen the same or higher population declines than Detroit.[68][69][70] Popper says the Great Plains is experiencing rural decline while Detroit is the foremost example of urban decline. For Detroit he suggests that the city try to concentrate existing population to stimulate development and provide better city services, with land banking of neighborhoods evaluated as unsalvageable in the near term.[71]

The decline has resulted in severe urban decay and thousands of empty homes, apartment buildings and commercial buildings around the city. Some parts of Detroit are so sparsely populated that the city has difficulty providing municipal services. The city has sought and considered various solutions such as demolition of abandoned homes and buildings; removal of street lighting from large portions of the city; and encouraging the small population in certain areas to move to more populated locations. It advises them that the city cannot provide as quick response for city services such as police in depopulated areas.[72][73][74][75][76]

More than half of the owners of Detroit's 305,000 properties failed to pay their 2011 tax bills, exacerbating the city's financial crisis. According to the Detroit News, 47 percent of the city's taxable parcels are delinquent on their 2011 tax bills, resulting in about $246 million in taxes and fees going uncollected, nearly half of which was due to Detroit. The rest of the money would have been earmarked for Wayne County, Detroit Public Schools and the library system. The review also found 77 blocks in Detroit had only one owner who paid taxes in 2011.[77]

High unemployment was compounded by middle-class flight to the suburbs and some residents leaving the state to find work. This left the city with a higher poor population, reduced tax base, depressed property values, abandoned buildings, abandoned neighborhoods, high crime rates and a pronounced demographic imbalance. Numerous stray dogs roam the city's derelict areas, with numbers estimated at 20,000.[78] Fifty-nine Detroit postal workers were attacked by stray dogs in 2010, according to a Detroit postmaster.[78]

The city's financial crisis resulted in the state of Michigan taking over administrative control of its government.[79] The state governor declared a financial emergency in March 2013, appointing Kevyn Orr as emergency manager. On July 18, 2013, Detroit became the largest U.S. city to file for bankruptcy, awaiting approval by a judge.[18] It was declared bankrupt by U.S. judge Stephen Rhodes on December 3, with an $18.5 billion debt. Rhodes accepted the city's contention that it is broke and that negotiations with its thousands of creditors were infeasible.[19]

Geography

Cityscape

Architecture

Seen in panorama, Detroit's waterfront shows a variety of architectural styles. The post modern Neo-Gothic spires of the One Detroit Center (1993) were designed to blend with the city's Art Deco skyscrapers. Together with the Renaissance Center, they form a distinctive and recognizable skyline. Examples of the Art Deco style include the Guardian Building and Penobscot Building downtown, as well as the Fisher Building and Cadillac Place in the New Center area near Wayne State University. Among the city's prominent structures are United States' largest Fox Theatre, the Detroit Opera House, and the Detroit Institute of Arts.[80][81]

While the Downtown and New Center areas contain high-rise buildings, the majority of the surrounding city consists of low-rise structures and single-family homes. Outside of the city's core, residential high-rises are found in upper-class neighborhoods such as the East Riverfront extending toward Grosse Pointe and the Palmer Park neighborhood just west of Woodward. The University Commons-Palmer Park district in northwest Detroit, near the University of Detroit Mercy and Marygrove College, anchors historic neighborhoods including Palmer Woods, Sherwood Forest, and the University District.

The National Register of Historic Places lists several area neighborhoods and districts. Neighborhoods constructed prior to World War II feature the architecture of the times, with wood-frame and brick houses in the working-class neighborhoods, larger brick homes in middle-class neighborhoods, and ornate mansions in upper-class neighborhoods such as Brush Park, Woodbridge, Indian Village, Palmer Woods, Boston-Edison, and others.

Some of the oldest neighborhoods are along the Woodward and East Jefferson corridors. Some newer residential construction may also be found along the Woodward corridor, the far west, and northeast. Some of the oldest extant neighborhoods include West Canfield and Brush Park, which have both seen multi-million dollar restorations and construction of new homes and condominiums.[52][82]

Many of the city's architecturally significant buildings have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places; the city has one of United States' largest surviving collections of late 19th- and early 20th-century buildings.[81] Architecturally significant churches and cathedrals in the city include St. Joseph's, Old St. Mary's, the Sweetest Heart of Mary, and the Cathedral of the Most Blessed Sacrament.[80]

The city has substantial activity in urban design, historic preservation, and architecture.[83] A number of downtown redevelopment projects—of which Campus Martius Park is one of the most notable—have revitalized parts of the city. Grand Circus Park stands near the city's theater district, Ford Field, home of the Detroit Lions, and Comerica Park, home of the Detroit Tigers.[80] Other projects include the demolition of the Ford Auditorium off of Jefferson St.

The Detroit International Riverfront includes a partially completed three-and-one-half mile riverfront promenade with a combination of parks, residential buildings, and commercial areas. It extends from Hart Plaza to the MacArthur Bridge accessing Belle Isle Park (the largest island park in a U.S. city). The riverfront includes Tri-Centennial State Park and Harbor, Michigan's first urban state park. The second phase is a two-mile (3 km) extension from Hart Plaza to the Ambassador Bridge for a total of five miles (8 km) of parkway from bridge to bridge. Civic planners envision that the pedestrian parks will stimulate residential redevelopment of riverfront properties condemned under eminent domain.

Other major parks include River Rouge (in the southwest side), the largest park in Detroit; Palmer (north of Highland Park) and Chene Park (on the east river downtown).[84]

Neighborhoods

Detroit has a variety of neighborhood types. The revitalized Downtown, Midtown, and New Center areas feature many historic buildings and are high density, while further out, particularly in the northeast and on the fringes,[85] high vacancy levels are problematic, for which a number of solutions have been proposed. In 2007, Downtown Detroit was recognized as a best city neighborhood in which to retire among the United States' largest metro areas by CNN Money Magazine editors.[86]

Lafayette Park is a revitalized neighborhood on the city's east side, part of the Ludwig Mies van der Rohe residential district.[87] The 78-acre (32 ha) development was originally called the Gratiot Park. Planned by Mies van der Rohe, Ludwig Hilberseimer and Alfred Caldwell it includes a landscaped, 19-acre (7.7 ha) park with no through traffic, in which these and other low-rise apartment buildings are situated.[87] Immigrants have contributed to the city's neighborhood revitalization, especially in southwest Detroit.[88] Southwest Detroit has experienced a thriving economy in recent years, as evidenced by new housing, increased business openings and the recently opened Mexicantown International Welcome Center.[89]

The city has numerous neighborhoods consisting of vacant properties resulting in low inhabited density in those areas, stretching city services and infrastructure. These neighborhoods are concentrated in the northeast and on the city's fringes.[85] A 2009 parcel survey found about a quarter of residential lots in the city to be undeveloped or vacant, and about 10% of the city's housing to be unoccupied.[85][91][92] The survey also reported that most (86%) of the city's homes are in good condition with a minority (9%) in fair condition needing only minor repairs.[91][92][93]

To deal with vacancy issues, the city has begun demolishing the derelict houses, razing 3,000 of the total 10,000 in 2010,[94] but the resulting low density creates a strain on the city's infrastructure. To remedy this, a number of solutions have been proposed including resident relocation from more sparsely populated neighborhoods and converting unused space to urban agricultural use, including Hantz Woodlands, though the city expects to be in the planning stages for up to another two years.[95][96]

Public funding and private investment have also been made with promises to rehabilitate neighborhoods. In April 2008, the city announced a $300-million stimulus plan to create jobs and revitalize neighborhoods, financed by city bonds and paid for by earmarking about 15% of the wagering tax.[95] The city's working plans for neighborhood revitalizations include 7-Mile/Livernois, Brightmoor, East English Village, Grand River/Greenfield, North End, and Osborn.[95] Private organizations have pledged substantial funding to the efforts.[97][98] Additionally, the city has cleared a 1,200-acre (490 ha) section of land for large-scale neighborhood construction, which the city is calling the Far Eastside Plan.[99] In 2011, Mayor Bing announced a plan to categorize neighborhoods by their needs and prioritize the most needed services for those neighborhoods.[100]

Topography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 142.87 square miles (370.03 km2), of which 138.75 square miles (359.36 km2) is land and 4.12 square miles (10.67 km2) is water.[2] Detroit is the principal city in Metro Detroit and Southeast Michigan situated in the Midwestern United States and the Great Lakes region.

The city slopes gently from the northwest to southeast on a till plain composed largely of glacial and lake clay. The most notable topographical feature in the city is the Detroit Moraine, a broad clay ridge on which the older portions of Detroit and Windsor sit atop, rising approximately 62 feet (19 m) above the river at its highest point.[101] The highest elevation in the city is located directly north of Gorham Playground on the northwest side approximately three blocks south of 8 Mile Road, at a height of 675 to 680 feet (206 to 207 m).[102] Detroit's lowest elevation is along the Detroit River, at a surface height of 572 feet (174 m).[103]

Belle Isle Park is a 982-acre (1.534 sq mi; 397 ha) island park in the Detroit River, between the Detroit and Windsor, Ontario. It is connected to the mainland by the MacArthur Bridge in Detroit. Belle Isle Park contains such attractions as the James Scott Memorial Fountain, the Belle Isle Conservatory, the Detroit Yacht Club on an adjacent island, a half-mile (800 m) beach, a golf course, a nature center, monuments, and gardens. The city skyline may be viewed from the island.

Three road systems cross the city: the original French template, with avenues radiating from the waterfront; and true north–south roads based on the Northwest Ordinance township system. The city is north of Windsor, Ontario. Detroit is the only major city along the U.S.–Canadian border in which one travels south in order to cross into Canada.

Detroit has four border crossings: the Ambassador Bridge and the Detroit–Windsor Tunnel provide motor vehicle thoroughfares, with the Michigan Central Railway Tunnel providing railroad access to and from Canada. The fourth border crossing is the Detroit–Windsor Truck Ferry, located near the Windsor Salt Mine and Zug Island. Near Zug Island, the southwest part of the city was developed over a 1,500-acre (610 ha) salt mine that is 1,100 feet (340 m) below the surface. The Detroit Salt Company mine has over 100 miles (160 km) of roads within.[104][105]

Climate

| Detroit | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Detroit and the rest of southeastern Michigan have a humid continental climate (Köppen Dfa) which is influenced by the Great Lakes; the city and close-in suburbs are part of USDA Hardiness zone 6b, with farther-out northern and western suburbs generally falling in zone 6a.[107] Winters are cold, with moderate snowfall and temperatures not rising above freezing on an average 44 days annually, while dropping to or below 0 °F (−18 °C) on an average 4.4 days a year; summers are warm to hot with temperatures exceeding 90 °F (32 °C) on 12 days.[106] The warm season runs from May to September. The monthly daily mean temperature ranges from 25.6 °F (−3.6 °C) in January to 73.6 °F (23.1 °C) in July. Official temperature extremes range from 105 °F (41 °C) on July 24, 1934 down to −21 °F (−29 °C) on January 21, 1984; the record low maximum is −4 °F (−20 °C) on January 19, 1994, while, conversely the record high minimum is 80 °F (27 °C) on August 1, 2006, the most recent of five occurrences.[106] A decade or two may pass between readings of 100 °F (38 °C) or higher, which last occurred July 17, 2012. The average window for freezing temperatures is October 20 thru April 22, allowing a growing season of 180 days.[106]

Precipitation is moderate and somewhat evenly distributed throughout the year, although the warmer months such as May and June average more, averaging 33.5 inches (850 mm) annually, but historically ranging from 20.49 in (520 mm) in 1963 to 47.70 in (1,212 mm) in 2011.[106] Snowfall, which typically falls in measurable amounts between November 15 through April 4 (occasionally in October and very rarely in May),[106] averages 42.5 inches (108 cm) per season, although historically ranging from 11.5 in (29 cm) in 1881−82 to 94.9 in (241 cm) in 2013−14.[106] A thick snowpack is not often seen, with an average of only 27.5 days with 3 in (7.6 cm) or more of snow cover.[106] Thunderstorms are frequent in the Detroit area. These usually occur during spring and summer.[108]

| Climate data for Detroit (DTW), 1981–2010 normals, extremes 1874–present[lower-alpha 1] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 67 (19) |

70 (21) |

86 (30) |

89 (32) |

95 (35) |

104 (40) |

105 (41) |

104 (40) |

100 (38) |

92 (33) |

81 (27) |

69 (21) |

105 (41) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 32.0 (0) |

35.2 (1.8) |

45.8 (7.7) |

59.1 (15.1) |

69.9 (21.1) |

79.3 (26.3) |

83.4 (28.6) |

81.4 (27.4) |

74.0 (23.3) |

61.6 (16.4) |

48.8 (9.3) |

36.1 (2.3) |

59.0 (15) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 19.1 (−7.2) |

21.0 (−6.1) |

28.6 (−1.9) |

39.4 (4.1) |

49.4 (9.7) |

59.5 (15.3) |

63.9 (17.7) |

62.6 (17) |

54.7 (12.6) |

43.3 (6.3) |

34.3 (1.3) |

24.1 (−4.4) |

41.8 (5.4) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −21 (−29) |

−20 (−29) |

−4 (−20) |

8 (−13) |

25 (−4) |

36 (2) |

42 (6) |

38 (3) |

29 (−2) |

17 (−8) |

0 (−18) |

−11 (−24) |

−21 (−29) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.96 (49.8) |

2.02 (51.3) |

2.28 (57.9) |

2.90 (73.7) |

3.38 (85.9) |

3.52 (89.4) |

3.37 (85.6) |

3.00 (76.2) |

3.27 (83.1) |

2.52 (64) |

2.79 (70.9) |

2.46 (62.5) |

33.47 (850.1) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.5 (31.8) |

10.2 (25.9) |

6.9 (17.5) |

1.7 (4.3) |

trace | 0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0.1 (0.3) |

1.5 (3.8) |

9.6 (24.4) |

42.5 (108) |

| Avg. precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.1 | 10.6 | 11.7 | 12.2 | 12.1 | 10.2 | 10.4 | 9.6 | 9.5 | 9.8 | 11.6 | 13.7 | 134.5 |

| Avg. snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 10.4 | 8.3 | 5.4 | 1.6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.2 | 2.3 | 8.5 | 36.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.7 | 72.5 | 70.0 | 66.0 | 65.3 | 67.3 | 68.5 | 71.5 | 73.4 | 71.6 | 74.6 | 76.7 | 71.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 119.9 | 138.3 | 184.9 | 217.0 | 275.9 | 301.8 | 317.0 | 283.5 | 227.6 | 176.0 | 106.3 | 87.7 | 2,435.9 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 41 | 47 | 50 | 54 | 61 | 66 | 69 | 66 | 61 | 51 | 36 | 31 | 55 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[106][109][110] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

City

| Historical populations | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Census | City[111] | Metro[112] | Region[113] | |

| 1810 | 1,650 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1820 | 1,422 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1830 | 2,222 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1840 | 9,102 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1850 | 21,019 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1860 | 45,619 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1870 | 79,577 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1880 | 116,340 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1890 | 205,877 | N/A | N/A | |

| 1900 | 285,704 | 542,452 | 664,771 | |

| 1910 | 465,766 | 725,064 | 867,250 | |

| 1920 | 993,678 | 1,426,704 | 1,639,006 | |

| 1930 | 1,568,662 | 2,325,739 | 2,655,395 | |

| 1940 | 1,623,452 | 2,544,287 | 2,911,681 | |

| 1950 | 1,849,568 | 3,219,256 | 3,700,490 | |

| 1960 | 1,670,144 | 4,012,607 | 4,660,480 | |

| 1970 | 1,514,063 | 4,490,902 | 5,289,766 | |

| 1980 | 1,203,368 | 4,387,783 | 5,203,269 | |

| 1990 | 1,027,974 | 4,266,654 | 5,095,695 | |

| 2000 | 951,270 | 4,441,551 | 5,357,538 | |

| 2010 | 713,777 | 4,296,250 | 5,218,852 | |

| *Estimates [3][4] Metro: Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) Region: Combined Statistical Area (CSA) | ||||

In the 2010 United States Census, the city had 713,777 residents, ranking it the 18th most populous city in the United States.[3][66]

The city became the 4th-largest in the nation in 1920, after only New York City, Chicago and Philadelphia, with the influence of the booming auto industry. At its peak population of 1,849,568, in the 1950 Census, the city was the 5th-largest in the United States, after New York City, Chicago, Philadelphia and Los Angeles. Of the large shrinking cities of the United States, Detroit has had the most dramatic decline in population of the past 60 years (down 1,135,971) and the second largest percentage decline (down 61.4%, second only to St. Louis, Missouri's 62.7%). While the decline in Detroit's population has been ongoing since 1950, the most dramatic period was the significant 25% decline between the 2000 and 2010 Census.[66]

The population collapse has resulted in large numbers of abandoned homes and commercial buildings, and areas of the city hit hard by urban decay.[72][73][74][75][76]

Detroit's 713,777 residents represent 269,445 households, and 162,924 families residing in the city. The population density was 5,144.3 people per square mile (1,895/km²). There were 349,170 housing units at an average density of 2,516.5 units per square mile (971.6/km²). Housing density has declined. The city has demolished thousands of Detroit's abandoned houses, planting some areas and in others allowing the growth of urban prairie.

Of the 269,445 households, 34.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 21.5% were married couples living together, 31.4% had a female householder with no husband present, 39.5% were non-families, 34.0% were made up of individuals, and 3.9% had someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older. Average household size was 2.59, and average family size was 3.36.

There is a wide distribution of age in the city, with 31.1% under the age of 18, 9.7% from 18 to 24, 29.5% from 25 to 44, 19.3% from 45 to 64, and 10.4% 65 years of age or older. The median age was 31 years. For every 100 females there were 89.1 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 83.5 males.

Surrounding areas

Metro Detroit is a six-county Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) with a population of 4,296,250—making it the 13th-largest MSA in the United States as enumerated by the 2010 United States Census (2010 Census).[8]

The Detroit region is a nine-county Combined Statistical Area (CSA) with a population of 5,218,852—making it the 12th-largest CSA in the United States as enumerated by the 2010 Census.[4] The Detroit-Windsor area, a commercial link straddling the Canada-U.S. border, has a total population of about 5,700,000.[9]

Immigration and the natural birth rate have not kept pace with the MSA's (nor CSA's) losses from death and migration since the 2000 United States Census.[114]

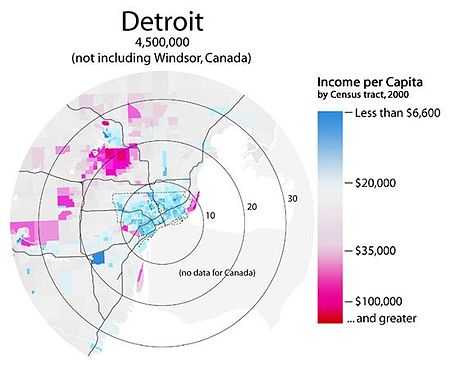

Income and employment

The loss of industrial and working-class jobs in the city has resulted in high rates of poverty and associated problems.[115] From 2000 to 2009, the city's estimated median household income fell from $29,526 to $26,098.[116] As of 2010 the mean income of Detroit is below the overall U.S. average by several thousand dollars. Of every three Detroit residents, one lives in poverty. Luke Bergmann, author of Getting Ghost: Two Young Lives and the Struggle for the Soul of an American City, said in 2010, "Detroit is now one of the poorest big cities in the country."[117]

In the 2010 American Community Survey, median household income in the city was $25,787, and the median income for a family was $31,011. The per capita income for the city was $14,118. 32.3% of families had income at or below the federally defined poverty level. Out of the total population, 53.6% of those under the age of 18 and 19.8% of those 65 and older had income at or below the federally defined poverty line.

Oakland County in Metro Detroit, once rated amongst the wealthiest US counties per household, is no longer shown in the top 25 listing of Forbes magazine. But internal county statistical methods – based on measuring per capita income for counties with more than one million residents – show that Oakland is still within the top 12, slipping from the 4th-most affluent such county in the U.S. in 2004 to 11th-most affluent in 2009.[118][119] [120] Detroit dominates Wayne County, which has an average household income of about $38,000, compared to Oakland County's $62,000.[121][122]

Race and ethnicity

As of the 2010 Census, the racial composition of the city was:

- 82.7% Black or African American;

- 10.6% White (7.8% non-Hispanic whites, 2.8% Hispanic whites);

- 3% from other races;

- 1.1% Asian;

- 2.2% from two or more races;

- 0.4% American Indian;

- 0.02% Pacific Islander.

In addition, 6.8% of the population self-identified as Hispanic or Latino, of any race, with ancestry mainly from Mexico and Puerto Rico.[123]

The city's population increased more than sixfold during the first half of the 20th century, fed largely by an influx of European, Middle Eastern (Lebanese, Assyrian/Chaldean), and Southern migrants to work in the burgeoning automobile industry.[124] In 1940, Whites were 90.4% of the city's population.[125] Since 1950 the city has seen a major shift in its population to the suburbs. In 1910, fewer than 6,000 blacks called the city home;[126] in 1930 more than 120,000 blacks lived in Detroit.[127] The thousands of African Americans who came to Detroit were part of the Great Migration of the 20th century.[128]

Detroit remains one of the most racially segregated cities in the United States.[129][130] From the 1940s to the 1970s a second wave of Blacks moved to Detroit to escape Jim Crow laws in the south and find jobs.[131] However, they soon found themselves excluded from white areas of the city—through violence, laws, and economic discrimination (e.g., redlining).[132] White residents attacked black homes: breaking windows, starting fires, and exploding bombs.[129][132] The pattern of segregation was later magnified by white migration to the suburbs.[130]

A traditional boundary between black and white is Eight Mile Road, which separates the city from suburbs to the north.[133]

One of the implications of racial segregation, which correlates with class segregation, may be overall worse health for some populations.[130][134]

According to the 2010 Census, segregation in Detroit has decreased in absolute and in relative terms. The number of integrated neighborhoods has increased from 100 in 2000 to 204 in 2010. The city has also moved down the ranking, from number one most segregated to number four.[135]

A 2011 op-ed in The New York Times attributed the decreased segregation rating to the overall exodus from the city, cautioning that these areas may soon become more segregated. This pattern already happened in the 1970s, when apparent integration was actually a precursor to white flight and resegregation.[129]

De facto educational segregation in Detroit (and by extension elsewhere) was legally permitted by the U.S. Supreme Court in Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974).[44]

In the first decade of the 21st century, about two-thirds of the total black population in metropolitan area resided within the city limits of Detroit.[17][136]

While Blacks/African-Americans comprised only 13 percent of Michigan's population in 2010, they made up nearly 82 percent of Detroit's population. The next largest population groups were Whites, at 10 percent, and Hispanic, at 6 percent.[137]

Over a 60-year period, white flight occurred in the city. According to an estimate of the Michigan Metropolitan Information Center, from 2008 to 2009 the percentage of non-Hispanic White residents increased from 8.4% to 13.3%. Some empty nesters and many younger White people moved into the city while many African Americans moved to the suburbs.[138]

Detroit has a Mexican-American population. In the early 20th century thousands of Mexicans came to Detroit to work in agricultural, automotive, and steel jobs. During the Mexican Repatriation of the 1930s many Mexicans in Detroit were willingly repatriated or forced to repatriate. By the 1940s the Mexican community began to settle what is now Mexicantown. The population significantly increased in the 1990s due to immigration from Jalisco. In 2010 Detroit had 48,679 Hispanics, including 36,452 Mexicans. The number of Hispanics was a 70% increase from the number in 1990.[139]

After World War II, many people from Appalachia settled in Detroit. Appalachians formed communities and their children acquired southern accents.[140] Many Lithuanians settled in Detroit during the World War II era, especially on the city's Southwest side in the West Vernor area, where the renovated Lithuanian Hall reopened in 2006.[141][142]

In 2001, 103,000 Jews, or about 1.9% of the population, were living in the Detroit area, in both Detroit and Ann Arbor.[143]

Also, Native Americans form a small but present community in Detroit with a Native American cultural center in nearby Redford Township.[144] In the 1930s and early 40s, thousands of Creek (Muscogee) and Cherokee from Oklahoma settled in Detroit.

Asians and Asian Americans

As of 2002, of all of the municipalities in the Wayne County-Oakland County-Macomb County area, Detroit had the second largest Asian population. As of that year Detroit's percentage of Asians was 1%, far lower than the 13.3% of Troy.[145] By 2000 Troy had the largest Asian American population in the tricounty area, surpassing Detroit.[146]

As of 2002 there are four areas in Detroit with significant Asian and Asian American populations. Northeast Detroit has population of Hmong with a smaller group of Lao people. A portion of Detroit next to eastern Hamtramck includes Bangladeshi Americans, Indian Americans, and Pakistani Americans; nearly all of the Bangladeshi population in Detroit lives in that area. Many of those residents own small businesses or work in blue collar jobs, and the population in that area is mostly Muslim. The area north of Downtown Detroit; including the region around the Henry Ford Hospital, the Detroit Medical Center, and Wayne State University; has transient Asian national origin residents who are university students or hospital workers. Few of them have permanent residency after schooling ends. They are mostly Chinese and Indian but the population also includes Filipinos, Koreans, and Pakistanis. In Southwest Detroit and western Detroit there are smaller, scattered Asian communities including an area in the westside adjacent to Dearborn and Redford Township that has a mostly Indian Asian population, and a community of Vietnamese and Laotians in Southwest Detroit.[145]

As of 2006 the city has one of the U.S.'s largest concentrations of Hmong Americans.[147] In 2006, the city had about 4,000 Hmong and other Asian immigrant families. Most Hmong live on residential streets east of Coleman Young Airport in proximity to Conner Avenue, Gratiot Avenue, and McNichols Avenue. Their social activities include family functions and activities offered at Osborn High School. Hmong immigrant families generally have lower incomes than those of suburban Asian families.[148] Michelle Lin, the coordinator of the Detroit Asian Youth (DAY) Project, said, "They think of themselves as Hmong. They think of themselves as Asian. 'Asian-American' is something more intangible that they can't really grasp."[148]

By 2001 many Bangladeshi Americans had moved from New York City, particularly Astoria, Queens, to the east side of Detroit and Hamtramck. Many moved because of lower costs of living, larger amounts of space, work available in small factories, and the large Muslim community in Metro Detroit. Many Bangladeshi Americans who moved into Queens, and then onwards to Metro Detroit had origins in Sylhet.[149] In 2002 over 80% of the Bangladeshi population within Wayne, Oakland, and Macomb counties lived in Hamtramck and some surrounding neighborhoods in Detroit.[150] That area overall had almost 1,500 ethnic Bangladeshis,[151] almost 75% of Bangladeshis in the entire State of Michigan.[146]

Economy

City

Several major corporations are based in the city, including three Fortune 500 companies. The most heavily represented sectors are manufacturing (particularly automotive), finance, technology, and health care. The most significant companies based in Detroit include: General Motors (downtown), Quicken Loans (downtown), Ally Financial (downtown), Compuware (downtown), Shinola (New Center), American Axle (North End), Meridian Health (downtown), Little Caesars (downtown), DTE Energy (downtown), Lowe Campbell Ewald (downtown), Blue Cross Blue Shield of Michigan (downtown), Rossetti Architects (downtown), and several prominent law firms.

About 80,500 people work in downtown Detroit, comprising one-fifth of the city's employment base.[152][153] Aside from the numerous Detroit-based companies listed above, downtown contains large offices for Comerica, Chrysler, HP Enterprise, Deloitte, PricewaterhouseCoopers, KPMG, and Ernst & Young. Ford Motor Company is located across the Rouge River from the city, in adjacent Dearborn.

Thousands more employees work a few miles north of downtown in Detroit's Midtown. Midtown's anchors are the Detroit Medical Center, the city's largest single employer, Wayne State University, and in New Center the Henry Ford Health System. Midtown is also home to watchmaker Shinola— its headquarters, factory and flagship store— and an array of small and/or startup companies. In New Center there’s TechTown, a research and business incubator hub that’s part of the WSU system.[154] Midtown, like downtown and Corktown, also has a fast-growing retailing and restaurant scene.

A number of the city's downtown employers are relatively new, as there has been a marked trend of companies moving from satellite suburbs around Metropolitan Detroit into the downtown core. Compuware completed its world headquarters in downtown Detroit in 2003. OnStar, Blue Cross Blue Shield, and HP Enterprise Services have located at the Renaissance Center. PricewaterhouseCoopers Plaza offices are adjacent to Ford Field, and Ernst & Young completed its office building at One Kennedy Square in 2006. Perhaps most prominently, in 2010, Quicken Loans, one of the largest mortgage lenders, relocated its world headquarters and 4,000 employees to downtown Detroit, consolidating its suburban offices, a move that its outspoken CEO Dan Gilbert intended to help revive the historic downtown area.[155] In July 2013, prominent advertising firm Lowe Campbell Ewald announced their move from Warren to Downtown Detroit to a building located adjacent to Ford Field.[156][157] In July 2012, the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office opened its Elijah J. McCoy Satellite Office in Detroit's Rivertown/Warehouse District as its first location outside Metropolitan Washington, DC.[158]

In April 2014, the Department of Labor reported the city's unemployment rate at 14.5%.[159]

The City and other private-public partnerships have attempted to catalyze the region's growth by facilitating the building and historical rehabilitation of residential high-rises in the center city, creating a wireless Internet zone, offering many business tax incentives, creating recreational spaces such as the Detroit RiverWalk, Campus Martius Park, Dequindre Cut Greenway, and midtown's Green Alleys. The City has cleared sections of land while retaining a number of historically significant vacant buildings in order to spur redevelopment;[160] though the city has struggled with finances, it issued bonds in 2008 to provide funding for ongoing work to demolish blighted properties.[95] In 2006, downtown Detroit reported $1.3 billion in restorations and new developments which increased the number of construction jobs in the city.[52] In the decade prior to 2006, downtown Detroit gained more than $15 billion in new investment from private and public sectors.[161]

Despite Detroit's recent financial issues, many developers remain unfazed by the city's problems.[162] Midtown Detroit is one of the most successful areas of Detroit with a residential occupancy rate of 96%.[163] Numerous developments have been recently completely or are in various stages of construction. These include the $82 million reconstruction of downtown's David Whitney Building, now an Aloft Hotel and luxury residences; the Woodward Garden Block Development in Detroit's midtown area; the residential conversion of the David Broderick Tower in downtown; the rehabilitation of the Book-Cadillac Hotel (now a Westin and luxury condos) and Fort-Shelby Hotel (now Doubletree) downtown, and numerous smaller projects.[164]

Downtown Detroit's population of young professionals is growing and retail is expanding.[165][166][167] A 2007 study found that Detroit's new downtown residents are predominantly young professionals (57 percent are ages 25–34, 45 percent have bachelor's degrees, 34 percent have a master's or professional degree),[152][165][168] a trend which has hastened over the last decade. John Varvatos is set to open a downtown store in 2015, and Restoration Hardware is rumored to be opening a store nearby.[160]

On June 5, 2013, Whole Foods Market opened a new 10 million dollar, 21,000-square-foot market at Woodward and Mack avenues in Midtown, its first store in the city of Detroit. Eight weeks later the CEO of Whole Foods said that the store was exceeding its wildest expectations.[169] On September 18, 2014, Whole Foods co-CEO Walter Robb said the company has plans to open a second market in Detroit.[170]

On July 25, 2013, Meijer, a midwestern retail chain, opened its first supercenter store in the city of Detroit,[171] a 20 million dollar, 190,000-square-foot store at 8 Mile Road and Woodward in the northern part of the city that is the centerpiece of a new 72 million dollar shopping center named Gateway Marketplace.[172] On June 30, 2014, Meijer started construction on its second supercenter store in Detroit.[173]

On May 21, 2014 JPMorgan Chase announced that it was injecting $100 million over five years into the Detroit economy, providing development funding for a variety of projects that would increase employment, population, and community programs. It is the largest commitment made to any one city by the nation's biggest bank. Of the $100 million, $50 million will go toward development projects, $25 million will go toward city blight removal, $12.5 million for job training, $7 million for small businesses in the city and, $5.5 million will go toward the M-1 light rail project.[174]

Surrounding areas

Detroit and the surrounding region constitute a major center of commerce and global trade, most notably as home to America's 'Big Three' automobile companies, General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler. Detroit's six county Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) has a population of about 4.3 million and a workforce of about 2.1 million.[175] In May 2012, the Department of Labor reported metropolitan Detroit's unemployment rate at 9.9%.[159][176] The Detroit MSA had a Gross Metropolitan Product (GMP) of $197.7 billion in 2010.[177]

| Top City Employers Source: Crain's Detroit Business[178] | |||||

| Rank | Company/Organization | # | |||

| 1 | Detroit Medical Center | 11,497 | |||

| 2 | City of Detroit | 9,591 | |||

| 3 | Quicken Loans | 9,192 | |||

| 4 | Henry Ford Health System | 8,807 | |||

| 5 | Detroit Public Schools | 6,586 | |||

| 6 | U.S. Government | 6,308 | |||

| 7 | Wayne State University | 6,023 | |||

| 8 | Chrysler | 5,426 | |||

| 9 | Blue Cross Blue Shield | 5,415 | |||

| 10 | General Motors | 4,327 | |||

| 11 | State of Michigan | 3,911 | |||

| 12 | DTE Energy | 3,700 | |||

| 13 | St. John Providence Health System | 3,566 | |||

| 14 | U.S. Postal Service | 2,643 | |||

| 15 | Wayne County | 2,566 | |||

| 16 | MGM Grand Detroit | 2,551 | |||

| 17 | MotorCity Casino | 1,973 | |||

| 18 | Compuware | 1,912 | |||

| 19 | Detroit Diesel | 1,685 | |||

| 20 | Greektown Casino | 1,521 | |||

| 21 | Comerica | 1,194 | |||

| 22 | Deloitte | 942 | |||

| 23 | Johnson Controls | 760 | |||

| 24 | PricewaterhouseCoopers | 756 | |||

| 25 | Ally Financial | 715 | |||

Labor force distribution in Detroit by category: Construction Manufacturing Trade, transportation, utilities Information Finance

Professional and business services

Education and health services

Leisure and hospitality

Other services

Government | |||||

Firms in the region pursue emerging technologies including biotechnology, nanotechnology, information technology, and hydrogen fuel cell development.

Metro Detroit area is one of the leading health care economies in the U.S. according to a 2003 study measuring health care industry components, with the region's hospital sector ranked fourth in the nation.[179]

Casino gaming plays an important economic role, with Detroit the largest city in the United States to offer casino resort hotels.[180] Caesars Windsor, Canada's largest, complements the MGM Grand Detroit, MotorCity Casino, and Greektown Casino in Detroit. The casino hotels contribute significant tax revenue along with thousands of jobs for residents. Gaming revenues have grown steadily, with Detroit ranked as the fifth largest gambling market in the United States for 2007. When Casino Windsor is included, Detroit's gambling market ranks third or fourth.

There are about four thousand factories in the area.[181] The domestic auto industry is primarily headquartered in Metro Detroit.

The area is also an important source of engineering job opportunities.[182] A 2004 Border Transportation Partnership study showed that 150,000 jobs in the Windsor-Detroit region and $13 billion in annual production depend on the City of Detroit's international border crossing.[183]

A rise in automated manufacturing using robotic technology has created related industries in the area.[184][185]

In addition to property taxes, residents pay an income tax rate of 2.50%.[186]

Detroit automakers and local manufacturers have made significant restructurings in response to market competition. GM made its initial public offering (IPO) of stock in 2010, after bankruptcy, bailout, and restructuring by the federal government.[187] Domestic automakers reported significant 2010 profits, interpreted by some analysts as indicating the beginning of an industry rebound and an economic recovery for the Detroit area.[188][189][190]

Culture and contemporary life

In the central portions of Detroit, the population of young professionals, artists, and other transplants is growing and retail is expanding.[165][166] This dynamic is luring additional new residents, and former residents returning from other cities, to the city's Downtown along with the revitalized Midtown and New Center areas.[152][152][165][165][166][168]

A desire to be closer to the urban scene has also attracted some young professionals to reside in inner ring suburbs such as Grosse Pointe and Royal Oak.[191] Detroit's proximity to Windsor, Ontario, provides for views and nightlife, along with Ontario's minimum drinking age of 19.[192] A 2011 study by Walk Score recognized Detroit for its above average walkability among large U.S. cities.[193] About two-thirds of suburban residents occasionally dine and attend cultural events or take in professional games in the city of Detroit.[194]

Entertainment and performing arts

Live music has been a prominent feature of Detroit's nightlife since the late 1940s, bringing the city recognition under the nickname 'Motown'. The metropolitan area has many nationally prominent live music venues. Concerts hosted by Live Nation perform throughout the Detroit area. Large concerts are held at DTE Energy Music Theatre and The Palace of Auburn Hills. The city's theatre venue circuit is the United States' second largest and hosts Broadway performances.[195][196]

Major theaters include the Fox Theatre (5,174 seats), Music Hall (1,770 seats), the Gem Theatre (451 seats), Masonic Temple Theatre (4,404 seats), the Detroit Opera House (2,765 seats), the Fisher Theatre (2,089 seats), The Fillmore Detroit (2,200 seats), St. Andrews Hall, the Majestic Theatre, and Orchestra Hall (2,286 seats) which hosts the renowned Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The Nederlander Organization, the largest controller of Broadway productions in New York City, originated with the purchase of the Detroit Opera House in 1922 by the Nederlander family.[16]

Motown Motion Picture Studios with 535,000 square feet (49,700 m2) produces movies in Detroit and the surrounding area based at the Pontiac Centerpoint Business Campus for a film industry expected to employ over 4,000 people in the metro area.[197]

The city of Detroit has a rich musical heritage and has contributed to a number of different genres over the decades leading into the new millennium.[16] Important music events in the city include: the Detroit International Jazz Festival, the Detroit Electronic Music Festival, the Motor City Music Conference (MC2), the Urban Organic Music Conference, the Concert of Colors, and the hip-hop Summer Jamz festival.[16]

In the 1940s, Detroit blues artist John Lee Hooker became a long-term resident in the city's southwest Delray neighborhood. Hooker, among other important blues musicians migrated from his home in Mississippi bringing the Delta Blues to northern cities like Detroit. Hooker recorded for Fortune Records, the biggest pre-Motown blues/soul label. During the 1950s, the city became a center for jazz, with stars performing in the Black Bottom neighborhood.[29] Prominent emerging Jazz musicians of the 1960s included: trumpet player Donald Byrd who attended Cass Tech and performed with Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers early in his career and Saxophonist Pepper Adams who enjoyed a solo career and accompanied Byrd on several albums. The Graystone International Jazz Museum documents jazz in Detroit.[198]

Other, prominent Motor City R&B stars in the 1950s and early 1960s was Nolan Strong, Andre Williams and Nathaniel Mayer – who all scored local and national hits on the Fortune Records label. According to Smokey Robinson, Strong was a primary influence on his voice as a teenager. The Fortune label was a family-operated label located on Third Avenue in Detroit, and was owned by the husband and wife team of Jack Brown and Devora Brown. Fortune, which also released country, gospel and rockabilly LPs and 45s, laid the groundwork for Motown, which became Detroit's most legendary record label.[199]

Berry Gordy, Jr. founded Motown Records which rose to prominence during the 1960s and early 1970s with acts such as Stevie Wonder, The Temptations, The Four Tops, Smokey Robinson & The Miracles, Diana Ross & The Supremes, the Jackson 5, Martha and the Vandellas, The Spinners, Gladys Knight & the Pips, The Marvelettes, The Elgins, The Monitors, The Velvelettes and Marvin Gaye. Artists were backed by in-house vocalists [200]The Andantes and The Funk Brothers, the Motown house band that was featured in Paul Justman's 2002 documentary film Standing in the Shadows of Motown, based on Allan Slutsky's book of the same name.

The Motown Sound played an important role in the crossover appeal with popular music, since it was the first African American owned record label to primarily feature African-American artists. Gordy moved Motown to Los Angeles in 1972 to pursue film production, but the company has since returned to Detroit. Aretha Franklin, another Detroit R&B star, carried the Motown Sound; however, she did not record with Berry's Motown Label.[16]

Local artists and bands rose to prominence in the 1960s and 70s including: the MC5, The Stooges, Bob Seger, Amboy Dukes featuring Ted Nugent, Mitch Ryder and The Detroit Wheels, Rare Earth, Alice Cooper, and Suzi Quatro. The group Kiss emphasized the city's connection with rock in the song Detroit Rock City and the movie produced in 1999. In the 1980s, Detroit was an important center of the hardcore punk rock underground with many nationally known bands coming out of the city and its suburbs, such as The Necros, The Meatmen, and Negative Approach.[199]

In the 1990s and the new millennium, the city has produced a number of influential hip hop artists, including Eminem, the hip-hop artist with the highest cumulative sales, hip-hop producer J Dilla, rapper and producer Esham and hip hop duo Insane Clown Posse. The city is also home to rappers Big Sean and Danny Brown. The band Sponge toured and produced music, with artists such as Kid Rock and Uncle Kracker.[16][199] The city also has an active garage rock genre that has generated national attention with acts such as: The White Stripes, The Von Bondies, The Detroit Cobras, The Dirtbombs, Electric Six, and The Hard Lessons.[16]

Detroit is cited as the birthplace of techno music in the early 1980s.[201] The city also lends its name to an early and pioneering genre of electronic dance music, "Detroit techno". Featuring science fiction imagery and robotic themes, its futuristic style was greatly influenced by the geography of Detroit's urban decline and its industrial past.[29] Prominent Detroit techno artists include Juan Atkins, Derrick May, and Kevin Saunderson. The Detroit Electronic Music Festival, now known as "Movement", occurs annually in late May on Memorial Day Weekend, and takes place in Hart Plaza. In the early years (2000-2002), this was a landmark event, boasting over a million estimated attendees annually, coming from all over the world to celebrate Techno music in the city of its birth.

Tourism

Many of the area's prominent museums are located in the historic cultural center neighborhood around Wayne State University and the College for Creative Studies. These museums include the Detroit Institute of Arts, the Detroit Historical Museum, Charles H. Wright Museum of African American History, the Detroit Science Center, as well as the main branch of the Detroit Public Library. Other cultural highlights include Motown Historical Museum, the Pewabic Pottery studio and school, the Tuskegee Airmen Museum, Fort Wayne, the Dossin Great Lakes Museum, the Museum of Contemporary Art Detroit (MOCAD), the Contemporary Art Institute of Detroit (CAID), and the Belle Isle Conservatory.