Design of experiments

In general usage, design of experiments (DOE) or experimental design is the design of any information-gathering exercises where variation is present, whether under the full control of the experimenter or not. However, in statistics, these terms are usually used for controlled experiments. Formal planned experimentation is often used in evaluating physical objects, chemical formulations, structures, components, and materials. Other types of study, and their design, are discussed in the articles on computer experiments, opinion polls and statistical surveys (which are types of observational study), natural experiments and quasi-experiments (for example, quasi-experimental design). See Experiment for the distinction between these types of experiments or studies.

In the design of experiments, the experimenter is often interested in the effect of some process or intervention (the "treatment") on some objects (the "experimental units"), which may be people, parts of people, groups of people, plants, animals, etc. Design of experiments is thus a discipline that has very broad application across all the natural and social sciences and engineering.

History of development

Controlled experimentation on scurvy

In 1747, while serving as surgeon on HMS Salisbury, James Lind carried out a controlled experiment to develop a cure for scurvy.[1]

Lind selected 12 men from the ship, all suffering from scurvy. Lind limited his subjects to men who "were as similar as I could have them", that is he provided strict entry requirements to reduce extraneous variation. He divided them into six pairs, giving each pair different supplements to their basic diet for two weeks. The treatments were all remedies that had been proposed:

- A quart of cider every day

- Twenty five gutts (drops) of vitriol (sulphuric acid) three times a day upon an empty stomach

- One half-pint of seawater every day

- A mixture of garlic, mustard, and horseradish in a lump the size of a nutmeg

- Two spoonfuls of vinegar three times a day

- Two oranges and one lemon every day

The men given citrus fruits recovered dramatically within a week. One of them returned to duty after six days, and the others cared for the rest. The other subjects experienced some improvement, but nothing compared to the subjects who ate the citrus fruits, which proved substantially superior to the other treatments.

Statistical experiments, following Charles S. Peirce

A theory of statistical inference was developed by Charles S. Peirce in "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" (1877–1878) and "A Theory of Probable Inference" (1883), two publications that emphasized the importance of randomization-based inference in statistics.

Randomized experiments

Charles S. Peirce randomly assigned volunteers to a blinded, repeated-measures design to evaluate their ability to discriminate weights.[2][3][4][5] Peirce's experiment inspired other researchers in psychology and education, which developed a research tradition of randomized experiments in laboratories and specialized textbooks in the 1800s.[2][3][4][5]

Optimal designs for regression models

Charles S. Peirce also contributed the first English-language publication on an optimal design for regression models in 1876.[6] A pioneering optimal design for polynomial regression was suggested by Gergonne in 1815. In 1918 Kirstine Smith published optimal designs for polynomials of degree six (and less).

Sequences of experiments

The use of a sequence of experiments, where the design of each may depend on the results of previous experiments, including the possible decision to stop experimenting, is within the scope of Sequential analysis, a field that was pioneered[7] by Abraham Wald in the context of sequential tests of statistical hypotheses.[8] Herman Chernoff wrote an overview of optimal sequential designs,[9] while adaptive designs have been surveyed by S. Zacks.[10] One specific type of sequential design is the "two-armed bandit", generalized to the multi-armed bandit, on which early work was done by Herbert Robbins in 1952.[11]

Principles of experimental design, following Ronald A. Fisher

A methodology for designing experiments was proposed by Ronald A. Fisher, in his innovative books: "The Arrangement of Field Experiments" (1926) and The Design of Experiments (1935). Much of his pioneering work dealt with agricultural applications of statistical methods. As a mundane example, he described how to test the hypothesis that a certain lady could distinguish by flavour alone whether the milk or the tea was first placed in the cup (AKA the "Lady tasting tea" experiment). These methods have been broadly adapted in the physical and social sciences, and are still used in agricultural engineering. The concepts presented here differ from the design and analysis of computer experiments.

- Comparison

- In some fields of study it is not possible to have independent measurements to a traceable standard. Comparisons between treatments are much more valuable and are usually preferable. Often one compares against a scientific control or traditional treatment that acts as baseline.

- Randomization

- Random assignment is the process of assigning individuals at random to groups or to different groups in an experiment. The random assignment of individuals to groups (or conditions within a group) distinguishes a rigorous, "true" experiment from an observational study or "quasi-experiment".[12] There is an extensive body of mathematical theory that explores the consequences of making the allocation of units to treatments by means of some random mechanism such as tables of random numbers, or the use of randomization devices such as playing cards or dice. Assigning units to treatments at random tends to mitigate confounding, which makes effects due to factors other than the treatment to appear to result from the treatment. The risks associated with random allocation (such as having a serious imbalance in a key characteristic between a treatment group and a control group) are calculable and hence can be managed down to an acceptable level by using enough experimental units. The results of an experiment can be generalized reliably from the experimental units to a larger population of units only if the experimental units are a random sample from the larger population; the probable error of such an extrapolation depends on the sample size, among other things. Random does not mean haphazard, and great care must be taken that appropriate random methods are used.

- Replication

- Measurements are usually subject to variation and uncertainty. Measurements are repeated and full experiments are replicated to help identify the sources of variation, to better estimate the true effects of treatments, to further strengthen the experiment's reliability and validity, and to add to the existing knowledge of the topic.[13] However, certain conditions must be met before the replication of the experiment is commenced: the original research question has been published in a peer-reviewed journal or widely cited, the researcher is independent of the original experiment, the researcher must first try to replicate the original findings using the original data, and the write-up should state that the study conducted is a replication study that tried to follow the original study as strictly as possible.[14]

- Blocking

- Blocking is the arrangement of experimental units into groups (blocks/lots) consisting of units that are similar to one another. Blocking reduces known but irrelevant sources of variation between units and thus allows greater precision in the estimation of the source of variation under study.

- Orthogonality concerns the forms of comparison (contrasts) that can be legitimately and efficiently carried out. Contrasts can be represented by vectors and sets of orthogonal contrasts are uncorrelated and independently distributed if the data are normal. Because of this independence, each orthogonal treatment provides different information to the others. If there are T treatments and T – 1 orthogonal contrasts, all the information that can be captured from the experiment is obtainable from the set of contrasts.

- Factorial experiments

- Use of factorial experiments instead of the one-factor-at-a-time method. These are efficient at evaluating the effects and possible interactions of several factors (independent variables). Analysis of experiment design is built on the foundation of the analysis of variance, a collection of models that partition the observed variance into components, according to what factors the experiment must estimate or test.

Example

This example is attributed to Harold Hotelling.[9] It conveys some of the flavor of those aspects of the subject that involve combinatorial designs.

Weights of eight objects are measured using a pan balance and set of standard weights. Each weighing measures the weight difference between objects in the left pan vs. any objects in the right pan by adding calibrated weights to the lighter pan until the balance is in equilibrium. Each measurement has a random error. The average error is zero; the standard deviations of the probability distribution of the errors is the same number σ on different weighings; and errors on different weighings are independent. Denote the true weights by

We consider two different experiments:

- Weigh each object in one pan, with the other pan empty. Let Xi be the measured weight of the ith object, for i = 1, ..., 8.

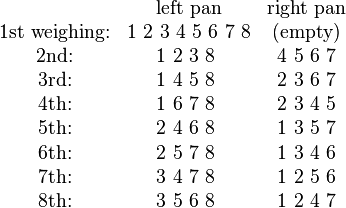

- Do the eight weighings according to the following schedule and let Yi be the measured difference for i = 1, ..., 8:

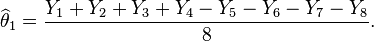

- Then the estimated value of the weight θ1 is

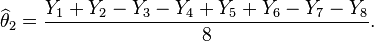

- Similar estimates can be found for the weights of the other items. For example

The question of design of experiments is: which experiment is better?

The variance of the estimate X1 of θ1 is σ2 if we use the first experiment. But if we use the second experiment, the variance of the estimate given above is σ2/8. Thus the second experiment gives us 8 times as much precision for the estimate of a single item, and estimates all items simultaneously, with the same precision. What the second experiment achieves with eight would require 64 weighings if the items are weighed separately. However, note that the estimates for the items obtained in the second experiment have errors that correlate with each other.

Many problems of the design of experiments involve combinatorial designs, as in this example and others.[15]

Avoiding false positives

False positive conclusions, often resulting from the pressure to publish or the author's own confirmation bias, are an inherent hazard in many fields, and experimental designs with undisclosed degrees of freedom are a problem.[16] This can lead to conscious or unconscious "p-hacking": trying multiple things until you get the desired result. It typically involves the manipulation - perhaps unconsciously - of the process of statistical analysis and the degrees of freedom until they return a figure below the p<.05 level of statistical significance.[17][18] So the design of the experiment should include a clear statement proposing the analyses to be undertaken.

Clear and complete documentation of the experimental methodology is also important in order to support replication of results.[19]

Discussion topics when setting up an experimental design

An experimental design or randomized clinical trial requires careful consideration of several factors before actually doing the experiment.[20] An experimental design is the laying out of a detailed experimental plan in advance of doing the experiment. Some of the following topics have already been discussed in the principles of experimental design section:

- How many factors does the design have? and are the levels of these factors fixed or random?

- Are control conditions needed, and what should they be?

- Manipulation checks; did the manipulation really work?

- What are the background variables?

- What is the sample size. How many units must be collected for the experiment to be generalisable and have enough power?

- What is the relevance of interactions between factors?

- What is the influence of delayed effects of substantive factors on outcomes?

- How do response shifts affect self-report measures?

- How feasible is repeated administration of the same measurement instruments to the same units at different occasions, with a post-test and follow-up tests?

- What about using a proxy pretest?

- Are there lurking variables?

- Should the client/patient, researcher or even the analyst of the data be blind to conditions?

- What is the feasibility of subsequent application of different conditions to the same units?

- How many of each control and noise factors should be taken into account?

Statistical control

It is best that a process be in reasonable statistical control prior to conducting designed experiments. When this is not possible, proper blocking, replication, and randomization allow for the careful conduct of designed experiments.[21] To control for nuisance variables, researchers institute control checks as additional measures. Investigators should ensure that uncontrolled influences (e.g., source credibility perception) do not skew the findings of the study. A manipulation check is one example of a control check. Manipulation checks allow investigators to isolate the chief variables to strengthen support that these variables are operating as planned.

One of the most important requirements of experimental research designs is the necessity of eliminating the effects of spurious, intervening, and antecedent variables. In the most basic model, cause (X) leads to effect (Y). But there could be a third variable (Z) that influences (Y), and X might not be the true cause at all. Z is said to be a spurious variable and must be controlled for. The same is true for intervening variables (a variable in between the supposed cause (X) and the effect (Y)), and anteceding variables (a variable prior to the supposed cause (X) that is the true cause). When a third variable is involved and has not been controlled for, the relation is said to be a zero order relationship. In most practical applications of experimental research designs there are several causes (X1, X2, X3). In most designs, only one of these causes is manipulated at a time.

Experimental designs after Fisher

Some efficient designs for estimating several main effects were found independently and in near succession by Raj Chandra Bose and K. Kishen in 1940 at the Indian Statistical Institute, but remained little known until the Plackett-Burman designs were published in Biometrika in 1946. About the same time, C. R. Rao introduced the concepts of orthogonal arrays as experimental designs. This concept played a central role in the development of Taguchi methods by Genichi Taguchi, which took place during his visit to Indian Statistical Institute in early 1950s. His methods were successfully applied and adopted by Japanese and Indian industries and subsequently were also embraced by US industry albeit with some reservations.

In 1950, Gertrude Mary Cox and William Gemmell Cochran published the book Experimental Designs, which became the major reference work on the design of experiments for statisticians for years afterwards.

Developments of the theory of linear models have encompassed and surpassed the cases that concerned early writers. Today, the theory rests on advanced topics in linear algebra, algebra and combinatorics.

As with other branches of statistics, experimental design is pursued using both frequentist and Bayesian approaches: In evaluating statistical procedures like experimental designs, frequentist statistics studies the sampling distribution while Bayesian statistics updates a probability distribution on the parameter space.

Some important contributors to the field of experimental designs are C. S. Peirce, R. A. Fisher, F. Yates, C. R. Rao, R. C. Bose, J. N. Srivastava, Shrikhande S. S., D. Raghavarao, W. G. Cochran, O. Kempthorne, W. T. Federer, V. V. Fedorov, A. S. Hedayat, J. A. Nelder, R. A. Bailey, J. Kiefer, W. J. Studden, A. Pázman, F. Pukelsheim, D. R. Cox, H. P. Wynn, A. C. Atkinson, G. E. P. Box and G. Taguchi. The textbooks of D. Montgomery and R. Myers have reached generations of students and practitioners.[22] [23] [24]

Human participant experimental design constraints

Laws and ethical considerations preclude some carefully designed experiments with human subjects. Legal constraints are dependent on jurisdiction. Constraints may involve institutional review boards, informed consent and confidentiality affecting both clinical (medical) trials and behavioral and social science experiments.[25] In the field of toxicology, for example, experimentation is performed on laboratory animals with the goal of defining safe exposure limits for humans.[26] Balancing the constraints are views from the medical field.[27] Regarding the randomization of patients, "... if no one knows which therapy is better, there is no ethical imperative to use one therapy or another." (p 380) Regarding experimental design, "...it is clearly not ethical to place subjects at risk to collect data in a poorly designed study when this situation can be easily avoided...". (p 393)

See also

- Adversarial collaboration

- Bayesian experimental design

- Clinical trial

- Computer experiment

- Control variable

- Controlling for a variable

- Experimetrics (econometrics-related experiments)

- Factor analysis

- First-in-man study

- Glossary of experimental design

- Grey box model

- Instrument effect

- Law of large numbers

- Manipulation checks

- Multifactor design of experiments software

- Probabilistic design

- Protocol (natural sciences)

- Quasi-experimental design

- Randomized block design

- Randomized controlled trial

- Research design

- Robust parameter design

- Supersaturated design

- Survey sampling

- System identification

- Taguchi methods

Notes

- ↑ Dunn, Peter (January 1997). "James Lind (1716-94) of Edinburgh and the treatment of scurvy". Archive of Disease in Childhood Foetal Neonatal (United Kingdom: British Medical Journal Publishing Group) 76 (1): 64–65. doi:10.1136/fn.76.1.F64. PMC 1720613. PMID 9059193. Retrieved 2009-01-17.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Peirce, Charles Sanders; Jastrow, Joseph (1885). "On Small Differences in Sensation". Memoirs of the National Academy of Sciences 3: 73–83.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Hacking, Ian (September 1988). "Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design". Isis 79 (3): 427–451. doi:10.1086/354775. JSTOR 234674. MR 1013489.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Stephen M. Stigler (November 1992). "A Historical View of Statistical Concepts in Psychology and Educational Research". American Journal of Education 101 (1): 60–70. doi:10.1086/444032. JSTOR 1085417.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Trudy Dehue (December 1997). "Deception, Efficiency, and Random Groups: Psychology and the Gradual Origination of the Random Group Design". Isis 88 (4): 653–673. doi:10.1086/383850. PMID 9519574.

- ↑ Peirce, C. S. (1876). "Note on the Theory of the Economy of Research". Coast Survey Report: 197–201., actually published 1879, NOAA PDF Eprint.

Reprinted in Collected Papers 7, paragraphs 139–157, also in Writings 4, pp. 72–78, and in Peirce, C. S. (July–August 1967). "Note on the Theory of the Economy of Research". Operations Research 15 (4): 643–648. doi:10.1287/opre.15.4.643. JSTOR 168276. - ↑ Johnson, N.L. (1961). "Sequential analysis: a survey." Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series A. Vol. 124 (3), 372–411. (pages 375–376)

- ↑ Wald, A. (1945) "Sequential Tests of Statistical Hypotheses", Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 16 (2), 117–186.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Herman Chernoff, Sequential Analysis and Optimal Design, SIAM Monograph, 1972.

- ↑ Zacks, S. (1996) "Adaptive Designs for Parametric Models". In: Ghosh, S. and Rao, C. R., (Eds) (1996). "Design and Analysis of Experiments," Handbook of Statistics, Volume 13. North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-82061-2. (pages 151–180)

- ↑ Robbins, H. (1952). "Some Aspects of the Sequential Design of Experiments". Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society 58 (5): 527–535. doi:10.1090/S0002-9904-1952-09620-8.

- ↑ Creswell, J.W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 2008, p. 300. ISBN 0-13-613550-1

- ↑ Dr. Hani (2009). "Replication study". Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ Burman, Leonard E.; Robert W. Reed; James Alm (2010). "A call for replication studies" (JOURNAL ARTICLE). Public Finance Review. pp. 787–793. doi:10.1177/1091142110385210. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ↑ Jack Sifri (8 December 2014). "How to Use Design of Experiments to Create Robust Designs With High Yield". youtube.com. Retrieved 2015-02-11.

- ↑ Simmons, Joseph; Leif Nelson; Uri Simonsohn (November 2011). "False-Positive Psychology: Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant". Psychological Science (Washington DC: Association for Psychological Science) 22 (11): 1359–1366. doi:10.1177/0956797611417632. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 22006061. Retrieved 29 January 2012.

- ↑ "Science, Trust And Psychology In Crisis". KPLU. 2014-06-02. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ↑ "Why Statistically Significant Studies Can Be Insignificant". Pacific Standard. 2014-06-04. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ↑ Chris Chambers (2014-06-10). "Physics envy: Do ‘hard’ sciences hold the solution to the replication crisis in psychology?". theguardian.com. Retrieved 2014-06-12.

- ↑ Ader, Mellenberg & Hand (2008) "Advising on Research Methods: A consultant's companion"

- ↑ Bisgaard, S (2008) "Must a Process be in Statistical Control before Conducting Designed Experiments?", Quality Engineering, ASQ, 20 (2), pp 143 - 176

- ↑ Montgomery, Douglas (2013). Design and analysis of experiments (8th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc. ISBN 9781118146927.

- ↑ Walpole, Ronald E.; Myers, Raymond H.; Myers, Sharon L.; Ye, Keying (2007). Probability & statistics for engineers & scientists (8 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall. ISBN 978-0131877115.

- ↑ Myers, Raymond H.; Montgomery, Douglas C.; Vining, G. Geoffrey; Robinson, Timothy J. (2010). Generalized linear models : with applications in engineering and the sciences (2 ed.). Hoboken, N.J: Wiley. ISBN 978-0470454633.

- ↑ Moore, David S.; Notz, William I. (2006). Statistics : concepts and controversies (6th ed.). New York: W.H. Freeman. pp. Chapter 7: Data ethics. ISBN 9780716786368.

- ↑ Ottoboni, M. Alice (1991). The dose makes the poison : a plain-language guide to toxicology (2nd ed.). New York, N.Y: Van Nostrand Reinhold. ISBN 0442006608.

- ↑ Glantz, Stanton A. (1992). Primer of biostatistics (3rd ed.). ISBN 0-07-023511-2.

References

- Peirce, C. S. (1877–1878), "Illustrations of the Logic of Science" (series), Popular Science Monthly, vols. 12-13. Relevant individual papers:

- (1878 March), "The Doctrine of Chances", Popular Science Monthly, v. 12, March issue, pp. 604–615. Internet Archive Eprint.

- (1878 April), "The Probability of Induction", Popular Science Monthly, v. 12, pp. 705–718. Internet Archive Eprint.

- (1878 June), "The Order of Nature", Popular Science Monthly, v. 13, pp. 203–217.Internet Archive Eprint.

- (1878 August), "Deduction, Induction, and Hypothesis", Popular Science Monthly, v. 13, pp. 470–482. Internet Archive Eprint.

- Peirce, C. S. (1883), "A Theory of Probable Inference", Studies in Logic, pp. 126-181, Little, Brown, and Company. (Reprinted 1983, John Benjamins Publishing Company, ISBN 90-272-3271-7)

Further reading

- Atkinson, A. C. and Donev, A. N. and Tobias, R. D. (2007). Optimum Experimental Designs, with SAS. Oxford University Press. pp. 511+xvi. ISBN 978-0-19-929660-6.

- Bailey, R.A. (2008). Design of Comparative Experiments. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68357-9. Pre-publication chapters are available on-line.

- Box, G. E. P., & Draper, N. R. (1987). Empirical model-building and response surfaces. New York: Wiley.

- Box, G. E., Hunter,W.G., Hunter, J.S., Hunter,W.G., "Statistics for Experimenters: Design, Innovation, and Discovery", 2nd Edition, Wiley, 2005, ISBN 0-471-71813-0

- Caliński, Tadeusz and Kageyama, Sanpei (2000). Block designs: A Randomization approach, Volume I: Analysis. Lecture Notes in Statistics 150. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-98578-6.

- George Casella (2008). Statistical design. Springer. ISBN 978-0-387-75965-4.

- Ghosh, S. and Rao, C. R., ed. (1996). Design and Analysis of Experiments. Handbook of Statistics 13. North-Holland. ISBN 0-444-82061-2.

- Goos, Peter and Jones, Bradley (2011). Optimal Design of Experiments: A Case Study Approach. Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-74461-1.

- Hacking, Ian (September 1988). "Telepathy: Origins of Randomization in Experimental Design". Isis 79 (3): 427–451. doi:10.1086/354775. JSTOR 234674. MR 1013489.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus and Kempthorne, Oscar (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments. I and II (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-470-38551-7.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus and Kempthorne, Oscar (2008). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume I: Introduction to Experimental Design (Second ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-72756-9.

- Hinkelmann, Klaus and Kempthorne, Oscar (2005). Design and Analysis of Experiments, Volume 2: Advanced Experimental Design (First ed.). Wiley. ISBN 978-0-471-55177-5.

- Mason, R. L., Gunst, R. F., & Hess, J. L. (1989). Statistical design and analysis of experiments with applications to engineering and science. New York: Wiley.

- Pearl, Judea. Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

- Peirce, C. S. (1876), "Note on the Theory of the Economy of Research", Appendix No. 14 in Coast Survey Report, pp. 197–201, NOAA PDF Eprint. Reprinted 1958 in Collected Papers of Charles Sanders Peirce 7, paragraphs 139–157 and in 1967 in Operations Research 15 (4): pp. 643–648, abstract at JSTOR. Peirce, C. S. (1967). "Note on the Theory of the Economy of Research". Operations Research 15 (4): 643. doi:10.1287/opre.15.4.643.

- Smith, Kirstine (1918). "On the Standard Deviations of Adjusted and Interpolated Values of an Observed Polynomial Function and its Constants and the Guidance They Give Towards a Proper Choice of the Distribution of the Observations". Biometrika 12 (1): 1–85. doi:10.2307/2331929.

- Taguchi, G. (1987). Jikken keikakuho (3rd ed., Vol I & II). Tokyo: Maruzen. English translation edited by D. Clausing. System of experimental design. New York: UNIPUB/Kraus International.

External links

| Library resources about Experimental design |

- A chapter from a "NIST/SEMATECH Handbook on Engineering Statistics" at NIST

- Box–Behnken designs from a "NIST/SEMATECH Handbook on Engineering Statistics" ] at NIST

- Articles on Design of Experiments

- Case Studies and Articles on Design of Experiments (DOE)

- Czitrom (1999) "One-Factor-at-a-Time Versus Designed Experiments", American Statistician, 53, 2.

- Design Resources Server a mobile library on Design of Experiments. The server is dynamic in nature and new additions would be posted on this site from time to time.

- Gosset: A General-Purpose Program for Designing Experiments

- SAS Examples for Experimental Design

- Matlab SUrrogate MOdeling Toolbox - SUMO Toolbox – Matlab code for Design of Experiments + Sequential Design + Surrogate Modeling

- Design DB: A database of combinatorial, statistical, experimental block designs

- The I-Optimal Design Assistant: a free on-line library of I-Optimal designs

- Warning Signs in Experimental Design and Interpretation by Peter Norvig, chief of research at Google

- Knowledge Base, Research Methods: A good explanation of the basic idea of experimental designs

- The Controlled Experiment vs. The Comparative Experiment: "How to experiment" for science fair projects

- Spall, J. C. (2010), "Factorial Design for Choosing Input Values in Experimentation: Generating Informative Data for System Identification," IEEE Control Systems Magazine, vol. 30(5), pp. 38–53. General introduction from a systems perspective

- DOE used for engine calibration reduces fuel consumption by 2 to 4 percent

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||