Denmark

| Kingdom of Denmark |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Anthem: Der er et yndigt land There is a lovely country Kong Christian stod ved højen mast[N 1] |

||||||

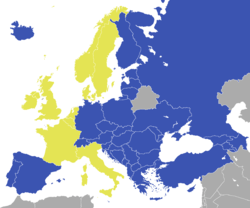

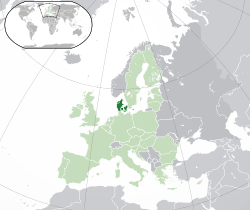

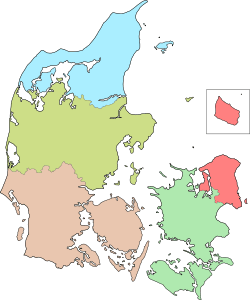

Location of Denmark[N 2] (dark green), in Europe (dark grey) and in the European Union (light green)

|

||||||

.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Copenhagen 55°43′N 12°34′E / 55.717°N 12.567°E | |||||

| Official languages | Danish | |||||

| Recognised regional languages | ||||||

| Religion | Evangelical Lutheranism | |||||

| Demonym | ||||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

|||||

| - | Monarch | Margrethe II | ||||

| - | Prime Minister | Helle Thorning-Schmidt | ||||

| Legislature | The Folketing | |||||

| Establishment | ||||||

| - | Consolidation | c. 10th century | ||||

| - | Constitutional Act | 5 June 1849 | ||||

| - | Danish Realm | 24 March 1948[N 4] | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Denmark[N 2] | 42,915.7 km2[2] (133rd) (16,562.1) sq mi |

||||

| - | Greenland | 2,166,086 km2 (836,330 sq mi) | ||||

| - | Faroe Islands | 1,399 km2 (540.16 sq mi) | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | January 2015 estimate | 5,659,715[3] (113th) | ||||

| - | Greenland | 56,370[4][N 5] | ||||

| - | Faroe Islands | 49,709[5][N 5] | ||||

| - | Density (Denmark) | 131/km2 339.3/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $255.866 billion[6][N 6] (52nd) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $45,451[6] (19th) | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2015 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $297.359 billion[6][N 6] (34th) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $52,822[6] (6th) | ||||

| Gini (2012) | low |

|||||

| HDI (2013) | very high · 10th |

|||||

| Currency | Danish krone[N 7] (DKK) | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | +45[N 8] | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | DK | |||||

| Internet TLD | .dk[N 9] | |||||

Denmark (![]() i/ˈdɛnmɑrk/; Danish: Danmark)[N 10] is a country in Northern Europe. The southernmost of the Nordic countries, it is located southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark forms part of the cultural region called Scandinavia, together with Sweden and Norway. The Kingdom of Denmark[N 11] is a sovereign state that comprises Denmark and two autonomous constituent countries in the North Atlantic Ocean: the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Denmark proper has an area of 43,094 square kilometres (16,639 sq mi),[9] and a population of 5,659,715 (January 2015).[3] The country consists of a peninsula, Jutland, and an archipelago of 443 named islands,[10] of which around 70 are inhabited. The islands are characterised by flat, arable land and sandy coasts, low elevation and a temperate climate.

i/ˈdɛnmɑrk/; Danish: Danmark)[N 10] is a country in Northern Europe. The southernmost of the Nordic countries, it is located southwest of Sweden and south of Norway, and bordered to the south by Germany. Denmark forms part of the cultural region called Scandinavia, together with Sweden and Norway. The Kingdom of Denmark[N 11] is a sovereign state that comprises Denmark and two autonomous constituent countries in the North Atlantic Ocean: the Faroe Islands and Greenland. Denmark proper has an area of 43,094 square kilometres (16,639 sq mi),[9] and a population of 5,659,715 (January 2015).[3] The country consists of a peninsula, Jutland, and an archipelago of 443 named islands,[10] of which around 70 are inhabited. The islands are characterised by flat, arable land and sandy coasts, low elevation and a temperate climate.

The unified kingdom of Denmark emerged in the 10th century as a proficient seafaring nation in the struggle for control of the Baltic Sea. Danish rule over the personal Kalmar Union, established in 1397 (over Norway and Sweden), ended with Swedish secession in 1523. However, Denmark still kept a union over Norway which lasted until its dissolution in 1814. Denmark inherited an expansive colonial empire from this union, of which the Faroe Islands and Greenland are remnants. Beginning in the 17th century, there were several cessions of territory; these culminated in the 1830s with a surge of nationalist movements, which were defeated in the 1864 Second Schleswig War. Denmark remained neutral during World War I. In April 1940, a German invasion saw brief military skirmishes while the Danish resistance movement was active from 1943 until the German surrender in May 1945. An industrialized exporter of agricultural produce in the second half of the 19th century, Denmark introduced social and labour-market reforms in the early 20th century, making the basis for the present welfare state model with a highly developed mixed economy.

The Constitution of Denmark was signed on 5 June 1849, ending the absolute monarchy which had begun in 1660. It establishes a constitutional monarchy—the current monarch is Queen Margrethe II—organised as a parliamentary democracy. The government and national parliament are seated in Copenhagen, the nation's capital, largest city and main commercial centre. Denmark[N 2] exercises hegemonic influence in the Danish Realm, devolving powers to handle internal affairs. Denmark became a member of the European Union in 1973, maintaining certain opt-outs; it retains its own currency, the krone. It is among the founding members of NATO, the Nordic Council, the OECD, OSCE, and the United Nations; it is also part of the Schengen Area.

Danes enjoy a high standard of living and the country ranks highly in numerous comparisons of national performance, including education, health care, protection of civil liberties, democratic governance, prosperity and human development.[12][13][14] Denmark is frequently ranked as one of the happiest countries in the world in cross-national studies of happiness.[15][16] The country ranks as having the world's highest social mobility,[17] a high level of income equality,[18] has one of the world's highest per capita incomes, and has one of the world's highest personal income tax rates.[19] A large majority of Danes are members of the National Church, though the Constitution guarantees freedom of religion.[20]

Etymology

The etymology of the word Denmark, and especially the relationship between Danes and Denmark and the unifying of Denmark as a single kingdom, is a subject which attracts debate.[21][22] This is centred primarily on the prefix "Dan" and whether it refers to the Dani or a historical person Dan and the exact meaning of the -"mark" ending. The issue is further complicated by a number of references to various Dani people in Scandinavia or other places in Europe in Greek and Roman accounts (like Ptolemy, Jordanes, and Gregory of Tours), as well as mediaeval literature (like Adam of Bremen, Beowulf, Widsith, and Poetic Edda).

Most handbooks derive the first part of the word, and the name of the people, from a word meaning "flat land",[23] related to German Tenne "threshing floor", English den "cave",.[23] The -mark is believed to mean woodland or borderland (see marches), with probable references to the border forests in south Schleswig.[24]

The first recorded use of the word Danmark within Denmark itself is found on the two Jelling stones, which are runestones believed to have been erected by Gorm the Old (c. 955) and Harald Bluetooth (c. 965). The larger stone of the two is popularly cited as Denmark's baptismal certificate (dåbsattest),[25] though both use the word "Denmark", in the form of accusative ᛏᛅᚾᛘᛅᚢᚱᚴ "tanmaurk" ([danmɒrk]) on the large stone, and genitive ᛏᛅᚾᛘᛅᚱᚴᛅᚱ "tanmarkar" (pronounced [danmarkaɽ]) on the small stone.[26] The inhabitants of Denmark are there called "tani" ([danɪ]), or "Danes", in the accusative.

History

Prehistory

The earliest archaeological findings in Denmark date back to the Eem interglacial period from 130,000–110,000 BC.[27] Denmark has been inhabited since around 12,500 BC and agriculture has been evident since 3900 BC.[28] The Nordic Bronze Age (1800–600 BC) in Denmark was marked by burial mounds, which left an abundance of findings including lurs and the Sun Chariot.

During the Pre-Roman Iron Age (500 BC – AD 1), native groups began migrating south, although[28] the first Danish people came to the country between the Pre-Roman and the Germanic Iron Age,[29] in the Roman Iron Age (AD 1–400). The Roman provinces maintained trade routes and relations with native tribes in Denmark, and Roman coins have been found in Denmark. Evidence of strong Celtic cultural influence dates from this period in Denmark and much of North-West Europe and is among other things reflected in the finding of the Gundestrup cauldron.

Historians believe that before the arrival of the precursors to the Danes, who came from the east Danish islands (Zealand) and Skåne and spoke an early form of North Germanic, most of Jutland and the nearest islands were settled by Jutes. They were later invited to Great Britain as mercenaries by Brythonic King Vortigern and were granted the south-eastern territories of Kent, the Isle of Wight among other areas, where they settled. They were later absorbed or ethnically cleansed by the invading Angles and Saxons, who formed the Anglo-Saxons. The remaining population in Jutland assimilated in with the Danes.

A short note about the Dani in "Getica" by the historian Jordanes is believed to be an early mention of the Danes, one of the ethnic groups from whom modern Danes are descended.[30][31] The Danevirke defence structures were built in phases from the 3rd century forward and the sheer size of the construction efforts in AD 737 are attributed to the emergence of a Danish king.[32][32] A new runic alphabet was first used around the same time and Ribe, the oldest town of Denmark, was founded about AD 700.

Viking and Middle Ages

From the 8th to the 10th century, the Danes, Norwegians and Swedes were known as Vikings. They colonized, raided, and traded in all parts of Europe. Viking explorers first discovered Iceland by accident in the 9th century, on the way towards the Faroe Islands and eventually came across "Vinland" (Land of wine), known today as Newfoundland, in Canada. The Danish Vikings were most active in the British Isles and Western Europe. They conquered and settled parts of England (known as the Danelaw) under King Sweyn Forkbeard in 1013, Ireland, and France where they founded Normandy. More Anglo-Saxon pence of this period have been found in Denmark than in England.[33]

As attested by the Jelling stones, the Danes were united and Christianised about 965 by Harald Bluetooth. It is believed that Denmark became Christian for political reasons so as not to get invaded by the rising Christian power in Europe, the Holy Roman Empire, which was an important trading area for the Danes. In that case Harald built six fortresses around Denmark called Trelleborg and built a further Danevirke. In the early 11th century, Canute the Great won and united Denmark, England, and Norway for almost 30 years.[33]

Throughout the High and Late Middle Ages, Denmark also included Skåneland (Skåne, Halland, and Blekinge) and Danish kings ruled Danish Estonia, as well as the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein. Most of the latter two now form the state of Schleswig-Holstein in northern Germany.

In 1397, Denmark entered into a personal union with Norway and Sweden, united under Queen Margaret I. The three countries were to be treated as equals in the union. However, even from the start Margaret may not have been so idealistic—treating Denmark as the clear "senior" partner of the union.[34] Thus, much of the next 125 years of Scandinavian history revolves around this union, with Sweden breaking off and being re-conquered repeatedly. The issue was for practical purposes resolved on 17 June 1523, as Swedish King Gustav Vasa conquered the city of Stockholm.

The Protestant Reformation came to Scandinavia in the 1530s, and following the Count's Feud civil war, Denmark converted to Lutheranism in 1536. Later that year, Denmark entered into a union with Norway.

Early modern history (1536–1849)

After Sweden permanently broke away from the Kalmar Union in 1523, Denmark tried on two occasions to reassert control over Sweden. The first was in the Northern Seven Years' War which lasted from 1563 until 1570. The second occasion was the Kalmar War when King Christian IV attacked Sweden in 1611 but failed to accomplish his main objective of forcing Sweden to return to the union with Denmark. The war led to no territorial changes, but Sweden was forced to pay a war indemnity of 1 million silver riksdaler to Denmark, an amount known as the Älvsborg ransom.[35] This turned out to be the last great Danish victory over Sweden. In the following decades Sweden gained the upper hand in the battles for supremacy in Scandinavia. Even today Sweden remains the largest Scandinavian country in terms of area and population.

King Christian used the money from the war reparations to found several towns and fortresses, most notably Glückstadt (founded as a rival to Hamburg), Christiania (following a fire destroying the original city of Oslo), Christianshavn, Christianstad, and Christiansand. Christian also constructed a number of buildings, most notably Børsen, Rundetårn, Nyboder, Rosenborg, a silver mine, and a copper mill. Inspired by the Dutch East India Company, he founded a similar Danish company and planned to claim Ceylon as a colony, but the company only managed to acquire Tranquebar on India's Coromandel Coast. Denmark's large colonial aspirations were limited to a few key trading posts in Africa and India. The empire was sustained by trade with other major powers, and plantations – ultimately a lack of resources led to its stagnation.[36]

In the Thirty Years' War, Christian tried to become the leader of the Lutheran states in Germany but suffered a crushing defeat at the Battle of Lutter.[37] The result was that the Catholic army under Albrecht von Wallenstein was able to invade, occupy, and pillage Jutland, forcing Denmark to withdraw from the war.[38] Denmark managed to avoid territorial concessions, but Gustavus Adolphus' intervention in Germany was seen as a sign that the military power of Sweden was on the rise while Denmark's influence in the region was declining. Swedish armies invaded Jutland in 1643 and claimed Skåne in 1644. According to Geoffrey Parker, "The Swedish occupation caused a drop in agricultural production and a shortage of capital; harvest failure and plague ravaged the land between 1647 and 1651; Denmark's population fell by 20 per cent."[39]

In the 1645 Treaty of Brømsebro, Denmark surrendered Halland, Gotland, the last parts of Danish Estonia, and several provinces in Norway. In 1657, King Frederick III declared war on Sweden and marched on Bremen-Verden. This led to a massive Danish defeat and the armies of King Charles X Gustav of Sweden conquered both Jutland, Funen, and much of Zealand before signing the Peace of Roskilde in February 1658 which gave Sweden control of Skåne, Blekinge, Trøndelag, and the island of Bornholm. Charles X Gustav quickly regretted not having destroyed Denmark completely and in August 1658 he began a two-year-long siege of Copenhagen but failed to take the capital. In the following peace settlement, Denmark managed to maintain its independence and regain control of Trøndelag and Bornholm.

Denmark tried to regain control of Skåne in the Scanian War (1675–79) but this attempt was a failure. Following the Great Northern War (1700–21), Denmark managed to restore control of the parts of Schleswig and Holstein ruled by the house of Holstein-Gottorp in 1721 and 1773, respectively. In the Napoleonic Wars, Denmark originally tried to pursue a policy of neutrality and trade with both France and the United Kingdom and joined the League of Armed Neutrality with Russia, Sweden, and Prussia. The British considered this a hostile act and attacked Copenhagen in both 1801 and 1807, in one case carrying off the Danish fleet, in the other, burning large parts of Copenhagen.

This led to the so-called Danish-British Gunboat War. The British control of the waterways between Denmark and Norway proved disastrous to the union's economy and in 1813, Denmark-Norway went bankrupt. The Danish-Norwegian union was dissolved by the Treaty of Kiel in 1814. In the treaty the Danish monarchy "irrevocably and forever" renounced claims to the Kingdom of Norway in favour of the Swedish king. After the dissolution of the union with Norway, Denmark kept the possessions of Iceland (which retained the Danish monarchy until 1944), the Faroe Islands, and Greenland.[40]

Constitutional monarchy (1849–present)

A nascent Danish liberal and national movement gained momentum in the 1830s; after the European Revolutions of 1848, Denmark peacefully became a constitutional monarchy on 5 June 1849. A two-chamber parliament was established. Denmark faced war against both Prussia and Habsburg Austria in what became known as the Second Schleswig War, lasting from February to October 1864. Denmark was easily defeated and obliged to cede Schleswig and Holstein to Prussia. This loss came as the latest in the long series of defeats and territorial loss that had begun in the 17th century. After these events, Denmark pursued a policy of neutrality in Europe.

Industrialization came to Denmark in the second half of the 19th century.[41] The nation's first railroads were constructed in the 1850s, and improved communications and overseas trade allowed industry to develop in spite of Denmark's lack of natural resources. Trade unions developed starting in the 1870s. There was a considerable migration of people from the countryside to the cities, and Danish agriculture became centred on the export of dairy and meat products.

Denmark maintained its neutral stance during the First World War. After the defeat of Germany, the Versailles powers offered to return the region of Schleswig-Holstein to Denmark. Fearing German irredentism, Denmark refused to consider the return of the area without a plebiscite. The two Schleswig Plebiscites took place on 10 February and 14 March 1920, respectively. On 10 July 1920, Northern Schleswig (Sønderjylland) was recovered by Denmark, thereby adding some 163,600 inhabitants and 3,984 square kilometres (1,538 sq mi). The reunion day (Genforeningsdag) is celebrated every 15 June on Valdemarsdag.

In 1939 Denmark signed a 10-year non-aggression pact with Nazi Germany but Germany invaded Denmark on 9 April 1940 and the Danish government quickly surrendered after only two hours of military resistance. World War II in Denmark was characterized by economic co-operation with Germany until 1943, when the Danish government refused further co-operation and its navy scuttled most of its ships and sent many of its officers to Sweden. The government and the Danish resistance performed a rescue operation that managed to evacuate several thousand Jews and their families to safety in Sweden before the Germans could send them to death camps. Some Danes supported nazism by joining the Danish Nazi Party or volunteering to fight with Germany as part of the Frikorps Danmark.[42] Iceland severed ties to Denmark and became an independent republic in 1944; Germany surrendered in May 1945; in 1948, the Faroe Islands gained home rule.

Post-war (1945–present)

After World War II, Denmark became one of the founding members of the European Free Trade Association, NATO, and the United Nations. During the 1960s, the EFTA countries were often referred to as the Outer Seven, as opposed to the Inner Six of what was then the European Economic Community (EEC).[43]

In 1973, along with Britain and Ireland, Denmark joined the European Economic Community after a public referendum. The Maastricht Treaty, which involved further European integration, was rejected by the Danish people in 1992; it was only accepted after a second referendum in 1993, which provided for four opt-outs from European Union policies (as outlined in the 1992 Edinburgh Agreement). The Danes rejected the euro as the national currency in a referendum in 2000. Greenland gained home rule in 1979 and was awarded self-determination in 2009. Neither the Faroe Islands nor Greenland are members of the Union, the Faroese having declined membership of the EEC in 1973 and Greenland in 1986, in both cases because of fisheries policies.

Constitutional change in 1953 led to a single-chamber parliament elected by proportional representation, female accession to the Danish throne, and Greenland becoming an integral part of Denmark. The Social Democrats led a string of coalition governments for most of the second half of the 20th century in a country generally known for its liberal traditions. Poul Schlüter then became the first Prime Minister from the Conservative People's Party in 1982, leading a centre-right coalition until 1993, when he was succeeded by the Social Democrat Poul Nyrup Rasmussen.

.jpg)

A centre-right coalition, headed by Anders Fogh Rasmussen, came to power in 2001 promising tighter immigration controls. A third successive centre-right leader, Lars Løkke Rasmussen, was Prime Minister from 2009 to 2011 due to Anders Fogh Rasmussen resigning to become the Secretary General of NATO. The Rasmussen governments were dependent on the right-wing populist Danish People's Party throughout the 2000s to push through legislation, during which time immigration and integration emerged as major issues of public debate. Helle Thorning-Schmidt from the Social Democrats became Denmark's first female Prime Minister in 2011, ending a decade of centre-right rule.

Despite its modest size, Denmark has participated in generally UN-sanctioned, and often NATO-led, military and humanitarian operations, including: Cyprus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Korea, Egypt, Croatia, Kosovo, Ethiopia, Afghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, and Libya.

Geography

Located in Northern Europe, Denmark[N 2] consists of the peninsula of Jutland and 443 named islands (1,419 islands above 100 square metres (1,100 sq ft) in total).[44] Of these, 74 are inhabited (January 2015),[45] with the largest being Zealand, the North Jutlandic Island, and Funen. The island of Bornholm is located east of the rest of the country, in the Baltic Sea. Many of the larger islands are connected by bridges; the Øresund Bridge connects Zealand with Sweden; the Great Belt Bridge connects Funen with Zealand; and the Little Belt Bridge connects Jutland with Funen. Ferries or small aircraft connect to the smaller islands. The largest cities with populations over 100,000 are the capital Copenhagen on Zealand; Aarhus and Aalborg in Jutland; and Odense on Funen.

The country occupies a total area of 43,094 square kilometres (16,639 sq mi)[9][46] The area of inland water is 700 km2 (270 sq mi), variously stated as from 500 - 700 km2 (193-270 sq m). The size of the land area cannot be stated exactly since the ocean constantly erodes and adds material to the coastline, and because of human land reclamation projects (to counter erosion). A circle enclosing the same area as Denmark would be 234 kilometres (more than 145 miles) in diameter with a circumference of 742 km (461 mi). It shares a border of 68 kilometres (42 mi) with Germany to the south and is otherwise surrounded by 8,750 km (5,437 mi) of tidal shoreline (including small bays and inlets).[47] No location in Denmark is further from the coast than 52 km (32 mi). On the south-west coast of Jutland, the tide is between 1 and 2 m (3.28 and 6.56 ft), and the tideline moves outward and inward on a 10 km (6.2 mi) stretch.[48] Denmark's territorial waters total 105,000 square kilometres (40,541 square miles).

Denmark's northernmost point is Skagen's point (the north beach of the Skaw) at 57° 45' 7" northern latitude; the southernmost is Gedser point (the southern tip of Falster) at 54° 33' 35" northern latitude; the westernmost point is Blåvandshuk at 8° 4' 22" eastern longitude; and the easternmost point is Østerskær at 15° 11' 55" eastern longitude. This is in the archipelago Ertholmene 18 kilometres (11 mi) north-east of Bornholm. The distance from east to west is 452 kilometres (281 mi), from north to south 368 kilometres (229 mi).

The country is flat with little elevation; having an average height above sea level of 31 metres (102 ft). The highest natural point is Møllehøj, at 170.86 metres (560.56 ft).[49] A sizeable portion of Denmark's terrain consists of rolling plains whilst the coastline is sandy, with large dunes in northern Jutland. Although once extensively forested, today Denmark largely consists of arable land. The country is drained by a dozen or so rivers, and the most significant include the Gudenå, Odense, Skjern, Suså and Vidå—a river that flows along its southern border with Germany.

The Kingdom of Denmark also includes the much larger, self-governing territory of Greenland, situated near North America and the autonomous territory of the Faroe Islands in the North Atlantic Ocean. Phytogeographically, the Kingdom belongs to the Boreal Kingdom and is shared between the Arctic, Atlantic European, and Central European provinces of the Circumboreal Region. According to the World Wide Fund for Nature, the territory of Denmark proper can be subdivided into two ecoregions: the Atlantic mixed forests and Baltic mixed forests. The Faroe Islands are covered by the Faroe Islands boreal grasslands, while Greenland hosts the ecoregions of Kalaallit Nunaat high arctic tundra and Kalaallit Nunaat low arctic tundra.

On 15 December 2014, the Government of the Kingdom of Denmark and Greenland presented a claim to the UN, claiming that the Lomonosov Ridge is connected to the continental shelf of Greenland, meaning that Denmark has territorial claim over the North Pole and other territory North of Greenland.[50]

Climate

Denmark has a temperate climate, characterised by mild winters, with mean temperatures in January of 1.5 °C (34.7 °F), and cool summers, with a mean temperature in August of 17.2 °C (63.0 °F).[51] Denmark has an average of 179 days per year with precipitation, on average receiving a total of 765 millimetres (30 in) per year; autumn is the wettest season and spring the driest.[51]

Because of Denmark's northern location, there are large seasonal variations in daylight. There are short days during the winter with sunrise coming around 8:45 am and sunset 3:45 pm (standard time), as well as long summer days with sunrise at 4:30 am and sunset at 10 pm (daylight saving time).[52]

The Faroe Islands has a mean temperature in January of 4.5 °C (40.1 °F), in July the mean temperature was 10.1 in 2012 and all that year it was 6.7 °C (44.1 °F). In 2012 the Faroe Islands had 195 days with precipitation and received a total of 1,262 millimetres (50 in) that year.[53]

| Climate data for Denmark (2001–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 3.3 (37.9) |

3.3 (37.9) |

6.1 (43) |

11.5 (52.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

18.5 (65.3) |

21.6 (70.9) |

21.2 (70.2) |

17.5 (63.5) |

12.3 (54.1) |

7.9 (46.2) |

4.2 (39.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 1.5 (34.7) |

1.2 (34.2) |

3.0 (37.4) |

7.5 (45.5) |

11.4 (52.5) |

14.6 (58.3) |

17.4 (63.3) |

17.2 (63) |

13.8 (56.8) |

9.4 (48.9) |

5.7 (42.3) |

2.2 (36) |

8.8 (47.8) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.8 (30.6) |

−1.3 (29.7) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

3.6 (38.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

10.6 (51.1) |

13.4 (56.1) |

13.5 (56.3) |

10.2 (50.4) |

6.2 (43.2) |

3.2 (37.8) |

−0.3 (31.5) |

5.5 (41.9) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 66 (2.6) |

50 (1.97) |

43 (1.69) |

37 (1.46) |

53 (2.09) |

68 (2.68) |

77 (3.03) |

91 (3.58) |

62 (2.44) |

83 (3.27) |

75 (2.95) |

61 (2.4) |

765 (30.12) |

| Avg. rainy days (≥ 1mm) | 18 | 15 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 14 | 17 | 20 | 17 | 181 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 47 | 71 | 146 | 198 | 235 | 239 | 232 | 196 | 162 | 111 | 58 | 45 | 1,739 |

| Source: Danmarks Meteorologiske Institut | |||||||||||||

Environment

Denmark has historically taken a progressive stance on environmental preservation; in 1971 Denmark established a Ministry of Environment and was the first country in the world to implement an environmental law in 1973.[54] To mitigate environmental degradation and global warming the Danish Government has signed the following international agreements: Antarctic Treaty; Climate Change-Kyoto Protocol etc.[46] However, Denmark’s per capita ecological footprint (global hectares demanded per person) was almost 8 gha compared to a world average of 1.7 gha in 2010, which was the fourth highest global footprint on a national level after Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates; contributing factors to this value are an exceptional high value for cropland but also a relatively high value for grazing land,[55] which can, in part, be explained by the substantially high meat consumption in Denmark (115.8 kg meat per capita and year, which is the second highest amount in the European union after Cyprus) and by the fact that meat and dairy industries play a large economic role in the country.[56]

Copenhagen is the spearhead of the bright green environmental movement in Denmark.[57] Copenhagen's most important environment research institutions are the University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen Business School,[58] Risø DTU National Laboratory for Sustainable Energy and the Technical University of Denmark, which Risø is now part of. Leading up to the 2009 United Nations Climate Change Conference (Copenhagen Summit), the University of Copenhagen held the Climate Change: Global Risks, Challenges and Decisions conference where the need for comprehensive action to mitigate climate change was stressed by the international scientific community. Notable figures such as Rajendra K. Pachauri, Chairman of the IPCC, Professor Nicholas Stern, author of the Stern Report, and Professor Daniel Kammen all emphasised the good example set by Copenhagen and Denmark in capitalising on cleantech and achieving economic growth while stabilising carbon emissions.

Denmark's greenhouse gas emissions per dollar of value produced has been for the most part unstable since 1990, seeing sudden growths and falls. Overall though, there has been a reduction in gas emissions per dollar value added to its market.[59] It lags behind other Nordic countries such as Norway[60] and Sweden.[61] In December 2014, the Climate Change Performance Index for 2015 placed Denmark at the top of the table, explaining that although emissions are still quite high, the country was able to implement effective climate protection policies.[62]

Administrative and statistical divisions

Denmark, with a total area of 43,094 square kilometres (16,639 sq mi), is divided into five administrative regions (Danish: regioner). Danmarks Statistik has divided the five regions into eleven provinces (landsdele). The provincial level is needed for statistical matters mainly. In national elections there are 10 provinces. Regions are divided into provinces except for North Jutland, which isn't divided and the region there equals the province as well. The Capital Region is divided into four provinces, of which the Baltic Sea island Bornholm comprices one province. The Greater Copenhagen metropolitan area consists of the other three provinces in the Capital Region together with the province Eastern Zealand.[63]

The regions are further subdivided into 98 municipalities (kommuner). The easternmost land in Denmark, the Ertholmene archipelago, with an area of 39 hectares (0.16 sq m), is neither part of a municipality nor a region but belongs to the Ministry of Defence.[64]

The regions were created on 1 January 2007 to replace the sixteen former counties. At the same time, smaller municipalities were merged into larger units, reducing the number from 270. Most municipalities have a population of at least 20,000 to give them financial and professional sustainability, although a few exceptions were made to this rule.[65] The administrative divisions are led by directly elected councils, elected proportionally every four years; the most recent Danish local elections were held on 19 November 2013. Other regional structures use the municipal boundaries as a layout, including the police districts, the court districts and the electoral wards.

Regions

The governing bodies of the regions are the regional councils with forty-one members elected for four-year terms. The head of the council is the regional council chairman (regionsrådsformand), who is elected by the council.[66] The areas of responsibility for the regional councils are the national health service, social services and regional development.[66] Unlike the counties they replaced, the regions are not allowed to levy taxes and the health service is primarily financed by a national health care contribution of eight per cent (sundhedsbidrag) combined with funds from both government and municipalities.[67] The wider responsibilities of the counties were transferred to the new, enlarged municipalities.

The area and populations of the regions vary widely; for example, the Capital Region, which encompasses the Copenhagen metropolitan area and the island of Bornholm, has a population three times larger than that of North Denmark Region, which covers the more sparsely populated area of northern Jutland. Under the county system certain densely populated municipalities, such as Copenhagen Municipality and Frederiksberg, had been given a status equivalent to that of counties, making them first-level administrative divisions. These sui generis municipalities were incorporated into the new regions under the 2007 reforms.

| Danish name | English name | Admin. centre | Largest city (populous) | Population (January 2015) | Total area (km²) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hovedstaden | Capital Region of Denmark | Hillerød | Copenhagen | 1,768,125 | 2,568.29 | |

| Midtjylland | Central Denmark Region | Viborg | Aarhus | 1,282,750 | 13,095.80 | |

| Nordjylland | North Denmark Region | Aalborg | Aalborg | 582,632 | 7,907.09 | |

| Sjælland | Region Zealand | Sorø | Roskilde | 820,480 | 7,268.75 | |

| Syddanmark | Region of Southern Denmark | Vejle | Odense | 1,205,728 | 12,132.21 | |

| Source: Regional and municipal key figures | ||||||

Greenland and the Faroe Islands

The Kingdom of Denmark is a unitary state that comprises, in addition to Denmark proper, two autonomous constituent countries in the North Atlantic Ocean, Greenland and the Faroe Islands. They have been integrated parts of the Danish Realm since the 18th century; however, due to their separate historical and cultural identities, these parts of the Realm have extensive autonomy and have assumed legislative and administrative responsibility in a substantial number of fields.[68] The Faroe Islands gained home rule in 1948 and Greenland in 1979, having previously had the status of counties.[69]

The two territories have their own home governments and legislatures and are effectively self-governing in regards to domestic affairs.[69] High Commissioners (Rigsombudsmand) act as representatives of the Danish government in the Faroese Løgting and in the Greenlandic Parliament, but they can not vote.[69] These devolved legislatures are subordinate to the Danish Parliament (Folketinget), where the two territories are represented by two seats each. The Faroese home government is defined to be an equal partner with the Danish national government,[70] while the Greenlandic people are defined as a separate people with the right to self-determination.[71]

| Constituent country | Population (2013) | Total area | Capital | National parliament | Prime Minister |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |

56,370[4] | 2,166,086 km2 (836,330 sq mi) | |

Inatsisartut | Kim Kielsen |

| |

49,709[5] | 1,399 km2 (540.16 sq mi) | |

Løgting | Kaj Leo Johannesen |

Governance

The Kingdom of Denmark is a constitutional monarchy, in which Queen Margrethe II is the head of state. The monarch officially retains executive power and presides over the Council of State (privy council).[72][73] However, following the introduction of a parliamentary system of government, the duties of the monarch have since become strictly representative and ceremonial,[74] such as the formal appointment and dismissal of the Prime Minister and other ministers in the executive government. The monarch is not answerable for his or her actions, and the monarch's person is sacrosanct.[75]

The Economist Intelligence Unit, while acknowledging that democracy is difficult to measure, listed Denmark 4th on its index of democracy.[12] Denmark, along with New Zealand, ranks 1st on the Corruption Perceptions Index, for government transparency and lack of corruption.[76]

Political system

The Danish political system operates under a framework laid out in the Constitution of Denmark. Changes to it require an absolute majority in two consecutive parliamentary terms and majority approval through a referendum (and the referendum majority must constitute at least 40 per cent of the electorate).[77] It has been revised four times, most recently in 1953.

The Folketing (Folketinget, "the people's assembly") is the unicameral national parliament, the supreme legislative body of Denmark. In theory, it has the ultimate legislative authority according to the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty; it is able to legislate on any matter and not bound by decisions of its predecessors. Legislation may be initiated by the government or by members of parliament. All bills passed must be presented before the Council of State to receive Royal Assent within thirty days in order to become law.[78]

Denmark is a constitutional monarchy and a representative democracy with universal suffrage. Membership of the Folketing is based on proportional representation of political parties,[79] with a 2% electoral threshold. Danes elect 175 members to the Folketing, with Greenland and the Faroe Islands electing an additional two members each.[80] Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years, but it is within the powers of the Prime Minister to ask the monarch to call for an election before the term has elapsed. On a vote of no confidence, the Folketing may force a single minister or the entire government to resign.[81]

Executive authority is exercised, formally on behalf of the monarch, by the Prime Minister and other cabinet ministers, who head ministries. The position of Prime Minister is allocated to the member of parliament who can obtain the confidence of a majority in the Folketing; this is usually the current leader of the largest political party or, more effectively, through a coalition of parties. A single party generally does not have sufficient political power in terms of the number of seats to form a government on its own. Denmark has often been ruled by coalition governments, themselves sometimes minority governments.[82]

Since the September 2011 election, Social Democrat Helle Thorning-Schmidt has been Prime Minister, initially heading a cabinet consisting of the Social Democrats, the Danish Social Liberal Party and the Socialist People's Party. She succeeded Lars Løkke Rasmussen, who had been heading a right-wing coalition cabinet comprising Venstre (a conservative-liberal party) and the Conservative People's Party, with parliamentary support from the national-conservative Danish People's Party. A second Thorning-Schmidt cabinet was formed on 3 February 2014, following the withdrawal of the Socialist People's Party.

Judicial system

The judicial system of Denmark is a civil law system divided between courts with regular civil and criminal jurisdiction and administrative courts with jurisdiction over litigation between individuals and the public administration. The Kingdom of Denmark does not have a single unified judicial system – Denmark has one system, Greenland another, and the Faroe Islands a third.[83] However, decisions by the highest courts in Greenland and the Faroe Islands may be appealed to the Danish High Courts. The Danish Supreme Court is the highest civil and criminal court responsible for the administration of justice in the Kingdom.

Articles sixty-two and sixty-four of the Constitution ensure judicial independence from government and Parliament by providing that judges shall only be guided by the law, including acts, statutes and practice.[84]

Foreign relations and the military

Foreign relations are substantially influenced by membership of the European Union (EU), which Denmark joined in 1973. It held the Presidency of the Council of the European Union on seven occasions, most recently from January to June 2012.[85] Following World War II, Denmark ended its two-hundred-year-long policy of neutrality. It has been a member of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) since its founding in 1949, and membership remains highly popular.[86] Denmark is today pursuing an active foreign policy, where human rights, democracy and other crucial values are to be defended actively. In recent years Greenland and the Faroe Islands have been guaranteed a say in foreign policy issues such as fishing, whaling, and geopolitical concerns.

The Kingdom of Denmark's armed forces are known as the Danish Defence (Danish: Forsvaret). During peacetime, the Ministry of Defence in Denmark employs around 33,000 in total. The main military branches employ almost 27,000: 15,460 in the Danish Army, 5,300 in the Royal Danish Navy and 6,050 in the Royal Danish Air Force (all including conscripts). The monarch is commander-in-chief of the Danish Defence, and serves as chief diplomatic official abroad.

The Danish Emergency Management Agency (Beredskabsstyrelsen) employs 2,000 (including conscripts), and about 4,000 are in non-branch-specific services like the Danish Defence Command, the Danish Defence Research Establishment and the Danish Defence Intelligence Service. Furthermore around 55,000 serve as volunteers in the Danish Home Guard (Hjemmeværnet).

The country is a strong supporter of international peacekeeping. The Danish Defence has around 1,400[87] staff in international missions, not including standing contributions to NATO SNMCMG1. The three largest contributions are in Afghanistan (ISAF), Kosovo (KFOR) and Lebanon (UNIFIL). Between 2003 and 2007, there were approximately 450 Danish soldiers in Iraq.[88] It has been involved in coordinating Western assistance to the Baltic states (Estonia,[89] Latvia, and Lithuania) in the Alliance.

Economy

Denmark has a high-income economy that ranks 21st in the world in terms of GDP (PPP) per capita and 10th in nominal GDP per capita. A liberalisation of import tariffs in 1797 marked the end of mercantilism and further liberalisation in the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century established the Danish liberal tradition in international trade that was only to be broken by the 1930s.[90][91] Property rights have enjoyed strong protection. Denmark's economy stands out as one of the most free in the Index of Economic Freedom and the Economic Freedom of the World.[92][93] Denmark is one of the most competitive economies in the world according to World Economic Forum 2008 report, IMD and The Economist.[94] The country also ranks highest in the world for workers' rights.[95] GDP per hour worked was the 13th highest in 2009. The country has a market income inequality close to the OECD average,[96][97] but after public cash transfers the income inequality is very low. According to the IMF, Denmark has the world's highest minimum wage.[98] As Denmark has no minimum wage law, the high wage floor has been attributed to the power of trade unions. For example, as the result of a collective bargaining agreement between the 3F trade union and the employers group Horesta, workers at McDonald's, Burger King and other fast food chains make the equivalent of $20 an hour, which is more than double what their counterparts earn in the United States, and have access to five weeks’ paid vacation, paid maternity and paternity leave and a pension plan.[99] The country has very high wealth inequality with a wealth Gini coefficient of 0.808. Denmark is among the countries with the highest credit rating.

As a result of its acclaimed "flexicurity" model, Denmark has the most free labour market in Europe, according to the World Bank. Employers can hire and fire whenever they want (flexibility), and between jobs, unemployment compensation is very high (security). The World Bank ranks Denmark as the easiest place in Europe to do business. Establishing a business can be done in a matter of hours and at very low costs.[100] No restrictions apply regarding overtime work, which allows companies to operate 24 hours a day, 365 days a year.[101] Denmark has a competitive company tax rate of 24.5% and a special time-limited tax regime for expatriates.[102] The Danish taxation system is broad based, with a 25% VAT, in addition to excise taxes, income taxes and other fees. The overall level of taxation (sum of all taxes, as a percentage of GDP) is estimated to be 46% in 2011.[103]

Denmark has the fourth highest ratio of tertiary degree holders in the world.[104] EF English Proficiency Index ranked Danes as the best non-native English speakers in the world.[105]

Once a predominantly agricultural country on account of its arable landscape, since 1945 Denmark has greatly expanded its industrial base so that by 2006 industry contributed about 25% of GDP and agriculture less than 2%.[106] In 2013, the 20 largest companies by turnover were A.P. Møller-Mærsk, Wrist Group, ISS, Novo Nordisk, Carlsberg, Dong Energy, Arla Foods, United Shipping & Trading Company, Danish Crown, Dansk Supermarked, Vestas Wind Systems, DLG, DSV, Coop Danmark, Danfoss, Statoil Refining Danmark, SAS Group, Skandinavisk Holding, TDC, and FLSmidth & Co..[107] Smaller notable companies include Grundfos and Lego Group. Denmark hasn't given birth to many young companies. As of 2013, only 3 of the 100 largest companies in Denmark were founded since 1970. For comparison, in California the number is over ten times higher.[108]

Denmark's currency, the krone (DKK), is pegged at approximately 7.46 kroner per euro through the ERM. Although a September 2000 referendum rejected adopting the euro,[109] the country in practice follows the policies set forth in the Economic and Monetary Union of the European Union and meets the economic convergence criteria needed to adopt the euro. The majority of the political parties in the parliament are for the euro, but as yet a new referendum has not been held, despite plans;[110] scepticism of the EU among Danish voters has historically been strong.

Support for free trade is high – in a 2007 poll 76% responded that globalisation is a good thing.[111] 70% of trade flows are inside the European Union. As of 2011, Denmark has the 10th highest export per capita in the world.[46] Denmark's main exports are: industrial production/manufactured goods 73.3% (of which machinery and instruments were 21.4%, and fuels (oil, natural gas), chemicals, etc. 26%); agricultural products and others for consumption 18.7% (in 2009 meat and meat products were 5.5% of total export; fish and fish products 2.9%).[46] Denmark is a net exporter of food and energy and has for a number of years had a balance of payments surplus while battling an equivalent of approximately 39% of GNP foreign debt or more than DKK 300 billion.[112]

StatBank is the name of a large statistical database maintained by the central authority of statistics in Denmark. Online distribution of statistics has been a part of the dissemination strategy in Denmark since 1985. In providing this service, Denmark is a leading nation in the electronic dissemination of government statistical data.

Energy

Denmark has considerably large deposits of oil and natural gas in the North Sea and ranks as number 32 in the world among net exporters of crude oil[113] and was producing 259,980 barrels of crude oil a day in 2009.[114] Most electricity is produced from coal, but 25–28% of electricity demand is supplied through wind turbines.[115] Denmark is a long-time leader in wind energy, and in May 2011 Denmark derived 3.1% of its gross domestic product from renewable (clean) energy technology and energy efficiency, or around €6.5 billion ($9.4 billion).[116] Denmark is connected by electric transmission lines to other European countries. On 6 September 2012, Denmark launched the biggest wind turbine in the world, and will add four more over the next four years.

Denmark's electricity sector has integrated energy sources such as wind power into the national grid. Denmark now aims to focus on intelligent battery systems (V2G) and plug-in vehicles in the transport sector.[117][118] The country is a member nation of the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA).[119]

Transport

Copenhagen Airport is Scandinavia's busiest passenger airport and handles over 21 million passengers a year. Other notable airports are Billund Airport, Aalborg Airport, and Aarhus Airport.

Significant investment has been made in building road and rail links between regions in Denmark, most notably the Great Belt Fixed Link, which connects Zealand and Funen. It is now possible to drive from Frederikshavn in northern Jutland to Copenhagen on eastern Zealand without leaving the motorway. The main railway operator is DSB for passenger services and DB Schenker Rail for freight trains. The railway tracks are maintained by Banedanmark. The North Sea and the Baltic Sea are intertwined by various, international ferry links. Construction of the Fehmarn Belt Fixed Link, connecting Denmark and Germany with a second link, will start in 2015.

Copenhagen has a Metro system, the Copenhagen Metro, and the Greater Copenhagen area has an extensive electrified suburban railway network, the S-train. In the four biggest cities - Copenhagen, Århus, Odense, Aalborg - light rail systems are planned to be in operation around 2020. The light rail in Greater Copenhagen will traverse 11 municipalities, providing a much needed corridor from Lyngby in the north to Ishøj in the south .[121] With Norway and Sweden, Denmark is part of the Scandinavian Airlines, and Copenhagen Airport forms the largest hub in Scandinavia.

Cycling in Denmark is a common form of transport, particularly for the young and for city dwellers. With a network of bicycle routes extending more than 12,000 km[122] and an estimated 7,000 km[123] of segregated dedicated bicycle paths and lanes, Denmark has a solid bicycle infrastructure.

Private vehicles are increasingly used as a means of transport. Because of the high registration tax (180%), VAT (25%), and one of the world's highest income tax rates, new cars are very expensive. The purpose of the tax is to discourage car ownership. The car fleet has increased by 45% over the last 30 years. In 2007, an attempt was made by the government to favour environmentally friendly cars by slightly reducing taxes on high mileage vehicles. However, this has had little effect, and in 2008 Denmark experienced an increase in the import of fuel inefficient old cars[124] primarily from Germany, as the cost for older cars—including taxes—keeps them within the budget of many Danes. The average car age (year 2011) is 9.2 years.[125]

Technology

In the 20th century, Danes have also been innovative in several fields of the technology sector. Danish companies have been influential in the shipping industry with the design of the largest and most energy efficient container ships in the world, and Danish engineers have contributed to the design of MAN Diesel engines. In the software and electronic field, Denmark contributed to design and manufacturing of Nordic Mobile Telephones, and the now-defunct Danish company DanCall was among the first to develop GSM mobile phones.[126]

Danish engineers are world-leading in providing diabetes care equipment and medication products from Novo Nordisk and, since 2000, the Danish biotech company Novozymes, the world market leader in enzymes for first generation starch based bioethanol, has pioneered development of enzymes for converting waste to cellulosic ethanol.[127] Medicon Valley, spanning the Øresund Region between Zealand and Sweden, is one of Europe's largest life science clusters, containing a large number of life science companies and research institutions located within a very small geographical area. Danish software engineers have taken leading roles in some of the world's important programming languages: Anders Hejlsberg, (Turbo Pascal, Delphi, C#); Rasmus Lerdorf, (PHP); Bjarne Stroustrup, (C++); David Heinemeier Hansson, (Ruby on Rails); Lars Bak, a pioneer in virtual machines (V8, Java VM, Dart); Lene Vestergaard Hau (physicist), the first person to stop light, leading to advances in quantum computing, nanoscale engineering and linear optics.

Public policy

After deregulating the labour market in the 1990s, Denmark has one of the most free labour markets among the European countries. According to World Bank labour market rankings, the labour market flexibility is at the same levels as the United States. The model is called Flexicurity. Denmark is also characterized by the Nordic model. The largest taxes are 25% value-added tax and personal income tax (minimum tax rate for adults is 42% scaling to over 60%, except for the residents of Ertholmene that escape the otherwise ubiquitous 8% healthcare tax fraction of the income taxes[129][130]). Other taxes include the registration tax on private vehicles, at a rate of 180%, on top of VAT. In July 2007, this was changed slightly in an attempt to favour more fuel efficient cars whilst maintaining the average taxation level.[131]

A growing number of people make contracts individually rather than collectively, and many (four out of ten employees) are contemplating dropping especially unemployment fund but occasionally even union membership altogether. The average employee receives a benefit at 47% of their wage level if they have to claim benefits when unemployed. With low unemployment, very few expect to be claiming benefits at all. The only reason then to pay the earmarked money to the unemployment fund would be to retire early and receive early retirement pay (efterløn), which is possible from the age of 60 provided an additional earmarked contribution is paid to the unemployment fund.[132]

In July 2013 the unemployment rate was at 6.7%, which was below the EU average of 10.9%.[133] The number of unemployed people is forecast to be 65,000 in 2015. The number of people in the working age group, less disability pensioners etc., will grow by 10,000 to 2,860,000, and jobs by 70,000 to 2,790,000;[134] part-time jobs are included.[135] Because of the present high demand and short supply of skilled labour, for instance for factory and service jobs, including hospital nurses and physicians, the annual average working hours have risen, especially compared with the recession 1987–1993.[136] Increasingly, service workers of all kinds are in demand, i.e. in the postal services and as bus drivers, and academics.[137] In the fall of 2007, more than 250,000 foreigners are working in the country, of which 23,000 still reside in Germany or Sweden.[138] According to a sampling survey of over 14,000 enterprises from December 2007 to April 2008 39,000 jobs were not filled, a number much lower than earlier surveys, confirming a downturn in the economic cycle.[139]

The level of unemployment benefits is dependent on former employment (the maximum benefit is at 90% of the wage) and at times also on membership of an unemployment fund, which is almost always—but need not be—administered by a trade union, and the previous payment of contributions. However, the largest share of the financing is still carried by the central government and is financed by general taxation, and only to a minor degree from earmarked contributions. There is no taxation, however, on proceeds gained from selling one's home (provided there was any home equity (friværdi)), as the marginal tax rate on capital income from housing savings is around 0%.[140] In 2011, 13.4% of Denmark's population was reported to live below the poverty line.[141] When adjusted for taxes and transfers, the poverty rate drops from 24% to 6%, one of the lowest of all OECD nations.[142][143]

Demographics

Population by ancestry (2012)[144]

According to 2012 figures from Statistics Denmark, 89.6% of Denmark's population of over 5,580,516 is of Danish descent (defined as having at least one parent who was born in Denmark and has Danish citizenship).[144][N 6] Many of the remaining 10.4% are immigrants—or descendants of recent immigrants—that came mainly from Turkey, Iraq, Somalia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, South Asia and the Middle East. Of the 10.4%, approximately 200,000 (34%) are of a Western background, and approx. 390,000 (66%) have a non-Western background (primarily Turkey, Iraq, Romani, Somalia, Pakistan, Iran, and Thailand).[145]

According to Feridun,[146] immigration has implications for the labor market in Denmark. Moreover, according to the figures from Danmarks Statistik, crime rate among refugees and their descendants is 73% higher than for the male population average, even when taking into account their socioeconomic background. A report from Teori- og Metodecentret from 2006 found that seven out of ten young people placed on the secured youth institutions in Denmark are immigrants (with 40 percent of them being refugees).[147]

The median age is 41.4 years, with 0.97 males per female. 99% of the population (age 15 and up) is literate. The fertility rate is 1.73 children born per woman (2013 est.). Despite the low birth rate, the population is still growing at an average annual rate of 0.23%.[46]

Denmark is frequently ranked as the happiest country in the world in cross-national studies of happiness.[15][16][148] This has been attributed to the country's highly regarded education and health care systems,[149] and its low level of income inequality.[7]

Languages

Danish is the de facto national language of Denmark and the official language of the Kingdom of Denmark.[150] Faroese and Greenlandic are the official regional languages of the Faroe Islands and Greenland respectively.[150] German is a recognised minority language in the area of the former South Jutland County (now part of the Region of Southern Denmark), which was part of the German Empire prior to the Treaty of Versailles.[150]

Danish and Faroese belong to the North Germanic (Nordic) branch of the Indo-European languages, along with Icelandic, Norwegian and Swedish.[151] The languages are so closely related that it is possible for Danish, Norwegian and Swedish speakers to understand each other with relatively little effort. Danish is more distantly related to German, which is a West Germanic language. Greenlandic or "Kalaallisut" belongs to the Eskimo–Aleut languages; it is closely related to the Inuit languages in Canada, such as Inuktitut, and entirely unrelated to Danish.[151]

A large majority (86%) of Danes speak English as a second language.[152] German is the second-most spoken foreign language, with 47% reporting a conversational level of proficiency.[150] Denmark had 25,900 native German speakers in 2007 (mostly in the Southern Jutland region).[150]

Religion

In January 2015, 77.8%[153] of the population of Denmark were members of the Church of Denmark (Den Danske Folkekirke), the officially established church, which is Lutheran in tradition.[154] This is down 0.6% compared to the year earlier and 1.3% down compared to two years earlier. Despite the high membership figures, only 3% of the population regularly attend Sunday services.[155][156]

The Constitution states that a member of the Royal Family must be a member of the Church of Denmark, though the rest of the population is free to adhere to other faiths.[157][158][159] In 1682 the state granted limited recognition to three religious groups dissenting from the Established Church: Roman Catholicism, the Reformed Church and Judaism,[159] although conversion to these groups from the Church of Denmark remained illegal initially. Until the 1970s, the state formally recognised "religious societies" by royal decree. Today, religious groups do not need official government recognition, they can be granted the right to perform weddings and other ceremonies without this recognition.[159]

Denmark's Muslims make up approximately 3% of the population and form the country's second largest religious community and largest minority religion.[155][160] As of 2009 there are nineteen recognised Muslim communities in Denmark.[160][161] As per an overview of various religions and denominations by the Danish Foreign Ministry, other religious groups comprise less than 1% of the population individually and approximately 2% when taken all together.[162]

According to a 2010 Eurobarometer Poll,[163] 28% of Danish citizens polled responded that they "believe there is a God", 47% responded that they "believe there is some sort of spirit or life force" and 24% responded that they "do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force". Another poll, carried out in 2009, found that 25% of Danes believe Jesus is the son of God, and 18% believe he is the saviour of the world.[164]

Education

The Danish education system provides access to primary school, secondary school and higher education. All college and university education in Denmark is free of charges; there are no tuition fees to enroll in courses. Students in secondary school or higher and aged 18 or above may apply for state educational support grants, known as Statens Uddannelsesstøtte (SU) which provides fixed financial support, disbursed monthly.[165] The Education Index lists Denmark 16th in 2011 based on mean years of schooling (of adults) and expected years of schooling (of children).[166]

Primary school is known as the folkeskole. Attendance at primary school is not compulsory, but most Danish children go to primary school for 10 years, from the age of 6 to 16. Whilst attending a primary school is not compulsory, receiving education at primary school-level is and must be provided for nine years. There are no final exams, but pupils in primary schools can choose to go to a test when finishing ninth grade. The test is obligatory if further education is to be attended. Pupils can alternatively attend a private independent school (friskole), or a private school (privatskole) – schools that are not under the administration of the municipalities, such as Christian schools or Waldorf schools.

Following graduation from primary school, there are several educational opportunities; the Gymnasium (STX) attaches importance in teaching a mix of humanities and science, Higher Technical Examination Programme (HTX) focuses on scientific subjects and the Higher Commercial Examination Programme emphasizes on subjects in economics. Higher Preparatory Examination (HF) is similar to Gymnasium (STX), but is one year shorter. For specific professions, there is the vocational education, training young people for work in specific trades by a combination of teaching and apprenticeship.

Danish universities and other higher education institutions offer international students a range of opportunities for obtaining an internationally recognised qualification in Denmark. Many programmes may be taught in the English language, the academic lingua franca, in bachelor's degrees, master's degrees, Ph.D.s and student exchange programmes.[167]

Health

As of 2012, Denmark has a life expectancy of 79.5 years at birth (77 for men, 82 for women), up from 75 years in 1990.[168] This ranks it 37th among 193 nations, behind the other Nordic countries. The National Institute of Public Health of the University of Southern Denmark has calculated 19 major risk factors among Danes that contribute to a lowering of the life expectancy; this includes smoking, alcohol, drug abuse and physical inactivity.[169] The large number of Danes becoming overweight is an increasing problem and results in an annual additional consumption in the health care system of DKK 1,625 million.[169]

Denmark has a universal health care system, characterised by being publicly financed through taxes and, for most of the services, run directly by the regional authorities. The primary source of income is a national health care contribution of 8 per cent (sundhedsbidrag), combined with funds from both government and municipalities.[67] This means that most health care provision is free at the point of delivery for all residents. Additionally, roughly two in five have complementary private insurance to cover services not fully covered by the state, such as physiotherapy.[170] As of 2012, Denmark spends 11.2% of its GDP on health care; this is up from 9.8% in 2007 (US$3,512 per capita).[170] This places Denmark above the OECD average and above the other Nordic countries.[170][171]

Culture

Denmark shares strong cultural and historic ties with its Scandinavian neighbours Sweden and Norway. It has historically been one of the most socially progressive cultures in the world. In 1969, Denmark was the first country to legalise pornography,[172] and in 2012, Denmark replaced its "registered partnership" laws, which it had been the first country to introduce in 1989,[173][174] with gender-neutral marriage.[175][176] Modesty, punctuality but above all equality are important aspects of the Danish way of life.[177]

The astronomical discoveries of Tycho Brahe (1546–1601), Ludwig A. Colding's (1815–88) neglected articulation of the principle of conservation of energy, and the contributions to atomic physics of Niels Bohr (1885–1962) indicate the range of Danish scientific achievement. The fairy tales of Hans Christian Andersen (1805–1875), the philosophical essays of Søren Kierkegaard (1813–55), the short stories of Karen Blixen (penname Isak Dinesen), (1885–1962), the plays of Ludvig Holberg (1684–1754), and the dense, aphoristic poetry of Piet Hein (1905–96), have earned international recognition, as have the symphonies of Carl Nielsen (1865–1931). From the mid-1990s, Danish films have attracted international attention, especially those associated with Dogme 95 like those of Lars von Trier.

There are three Danish heritage sites inscribed on the UNESCO World Heritage list in Northern Europe: Roskilde Cathedral, the main burial site for Danish monarchs since the 15th century; Kronborg castle, immortalized in the play Hamlet; and the Jelling stones, carved runestones that are often called Denmark's "baptismal certificate."

Popular media

Danish cinema dates back to 1897 and since the 1980s has maintained a steady stream of product due largely to funding by the state-supported Danish Film Institute. There have been three big internationally important waves of Danish cinema: erotic melodrama of the silent era; the increasingly explicit sex films of the 1960s and 1970s; and lastly, the Dogme 95 movement of the late 1990s, where directors often used hand-held cameras to dynamic effect in a conscious reaction against big-budget studios. Danish films have been noted for their realism, religious and moral themes, sexual frankness and technical innovation. The Danish filmmaker Carl Th. Dreyer (1889–1968) is considered one of the greatest directors of early cinema.[178][179]

Other Danish filmmakers of note include Erik Balling, the creator of the popular Olsen-banden films; Gabriel Axel, an Oscar-winner for Babette's Feast in 1987; and Bille August, the Oscar-, Palme d'Or- and Golden Globe-winner for Pelle the Conqueror in 1988. In the modern era, notable filmmakers in Denmark include Lars von Trier, who co-created the Dogme movement, and multiple award-winners Susanne Bier and Nicolas Winding Refn. Mads Mikkelsen is a world-renowned Danish actor, having starred in films such as King Arthur, Casino Royale, the Danish film The Hunt, and currently in the American TV series Hannibal. Another renowned Danish actor Nikolaj Coster-Waldau is internationally known for playing the role of Jaime Lannister in the critically acclaimed HBO series Game of Thrones.

Danish mass media and news programming are dominated by a few large corporations. In printed media JP/Politikens Hus and Berlingske Media, between them, control the largest newspapers Politiken, Berlingske Tidende and Jyllands-Posten and major tabloids B.T. and Ekstra Bladet. In television, publicly owned stations DR and TV 2 have large shares of the viewers.[180] Especially DR is famous for its high quality TV-series often sold to foreign broadcast and often with strong leading female characters like internationally known actresses Sidse Babett Knudsen and Sofie Gråbøl. In radio, DR has a near monopoly, currently broadcasting on all four nationally available FM channels, competing only with local stations.[181]

| Carl Nielsen Wind Quintet, Op. 43 1st movement |

|---|

| |

Copenhagen and its multiple outlying islands have a wide range of folk traditions. The Royal Danish Orchestra is among the world's oldest orchestras.[182] Denmark's most famous classical composer is Carl Nielsen, especially remembered for his six symphonies and his Wind Quintet, while the Royal Danish Ballet specializes in the work of the Danish choreographer August Bournonville. Danes have distinguished themselves as jazz musicians, and the Copenhagen Jazz Festival has acquired an international reputation. The modern pop and rock scene has produced a few names of note, including Aqua, D-A-D, The Raveonettes, Michael Learns to Rock, Alphabeat, Kashmir and Mew, among others. All together, Lars Ulrich, the drummer of the band Metallica, has become the first Danish musician to be inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

More recently, in 2013 Denmark entered the Eurovision Song Contest and won with Emmelie de Forest's song "Only Teardrops". The 2014 contest was hosted in Copenhagen.[183]

Architecture and design

Denmark's architecture became firmly established in the Middle Ages when first Romanesque, then Gothic churches and cathedrals sprang up throughout the country. From the 16th century, Dutch and Flemish designers were brought to Denmark, initially to improve the country's fortifications, but increasingly to build magnificent royal castles and palaces in the Renaissance style. During the 17th century, many impressive buildings were built in the Baroque style, both in the capital and the provinces. Neoclassicism from France was slowly adopted by native Danish architects who increasingly participated in defining architectural style. A productive period of Historicism ultimately merged into the 19th-century National Romantic style.[184]

The 20th century brought along new architectural styles; including expressionism, best exemplified by the designs of architect Peder Vilhelm Jensen-Klint, which relied heavily on Scandinavian brick Gothic traditions; and Nordic Classicism, which enjoyed brief popularity in the early decades of the century. It was in the 1960s that Danish architects such as Arne Jacobsen entered the world scene with their highly successful Functionalist architecture. This, in turn, has evolved into more recent world-class masterpieces including Jørn Utzon's Sydney Opera House and Johan Otto von Spreckelsen's Grande Arche de la Défense in Paris, paving the way for a number of contemporary Danish designers such as Bjarke Ingels to be rewarded for excellence both at home and abroad.[185]

Danish design is a term often used to describe a style of functionalistic design and architecture that was developed in mid-20th century, originating in Denmark. Danish design is typically applied to industrial design, furniture and household objects, which have won many international awards.

The Danish Porcelain Factory ("Royal Copenhagen") is famous for the quality of its ceramics and export products worldwide. Danish design is also a well-known brand, often associated with world-famous, 20th-century designers and architects such as Børge Mogensen, Finn Juhl, Hans Wegner, Arne Jacobsen, Poul Henningsen and Verner Panton.[186]

Other designers of note include Kristian Solmer Vedel (1923–2003) in the area of industrial design, Jens Harald Quistgaard (1919–2008) for kitchen furniture and implements and Ole Wanscher (1903–1985) who had a classical approach to furniture design.

Literature and philosophy

The first known Danish literature is myths and folklore from the 10th and 11th century. Saxo Grammaticus, normally considered the first Danish writer, worked for bishop Absalon on a chronicle of Danish history (Gesta Danorum). Very little is known of other Danish literature from the Middle Ages. With the Age of Enlightenment came Ludvig Holberg whose comedy plays are still being performed.

In the late 19th century, literature was seen as a way to influence society. Known as the Modern Breakthrough, this movement was championed by Georg Brandes, Henrik Pontoppidan (awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature) and J. P. Jacobsen. Romanticism influenced the renowned writer and poet Hans Christian Andersen, known for his stories and fairy tales, e.g. The Ugly Duckling, The Little Mermaid and The Snow Queen. In recent history Johannes Vilhelm Jensen was also awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature. Karen Blixen is famous for her novels and short stories. Other Danish writers of importance are Herman Bang, Gustav Wied, William Heinesen, Martin Andersen Nexø, Piet Hein, Hans Scherfig, Klaus Rifbjerg, Dan Turèll, Tove Ditlevsen, Inger Christensen and Peter Høeg.

Danish philosophy has a long tradition as part of Western philosophy. Perhaps the most influential Danish philosopher was Søren Kierkegaard, the creator of Christian existentialism. Kierkegaard had a few Danish followers, including Harald Høffding, who later in his life moved on to join the movement of positivism. Among Kierkegaard's other followers include Jean-Paul Sartre who was impressed with Kierkegaard's views on the individual, and Rollo May, who helped create humanistic psychology. Another Danish philosopher of note is Grundtvig, whose philosophy gave rise to a new form of non-aggressive nationalism in Denmark, and who is also influential for his theological and historical works.

Painting and photography

While Danish art was influenced over the centuries by trends in Germany and the Netherlands, the 15th- and 16th-century church frescos, which can be seen in many of the country's older churches, are of particular interest as they were painted in a style typical of native Danish painters.[187]

The Danish Golden Age, which began in the first half of the 19th century, was inspired by a new feeling of nationalism and romanticism, typified in the later previous century by history painter Nicolai Abildgaard. Christoffer Wilhelm Eckersberg was not only a productive artist in his own right but taught at the Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts where his students included notable painters such as Wilhelm Bendz, Christen Købke, Martinus Rørbye, Constantin Hansen, and Wilhelm Marstrand. The sculpture of Bertel Thorvaldsen was also significant during this period.[188]

In 1871, Holger Drachmann and Karl Madsen visited Skagen in the far north of Jutland where they quickly built up one of Scandinavia's most successful artists' colonies specializing in Naturalism and Realism rather than in the traditional approach favoured by the Academy. Hosted by Michael and his wife Anna, they were soon joined by P.S. Krøyer, Carl Locher and Laurits Tuxen. All participated in painting the natural surroundings and local people.[189] Similar trends developed on Funen with the Fynboerne who included Johannes Larsen, Fritz Syberg and Peter Hansen,[190] and on the island of Bornholm with the Bornholm school of painters including Niels Lergaard, Kræsten Iversen and Oluf Høst.[191]

Danish photography has developed from strong participation and interest in the very beginnings of the art in 1839 to the success of a considerable number of Danes in the world of photography today. Pioneers such as Mads Alstrup and Georg Emil Hansen paved the way for a rapidly growing profession during the last half of the 19th century while both artistic and press photographers made internationally recognised contributions. Today Danish photographers such as Astrid Kruse Jensen and Jacob Aue Sobol are active both at home and abroad, participating in key exhibitions around the world.[192]

Collections of modern art enjoy unusually attractive settings at the Louisiana Museum of Modern Art north of Copenhagen and at the North Jutland Art Museum in Aalborg. Notable artists include the Neo-Expressionist Per Kirkeby, Tal R with his wild and colourful paintings,[193] Olafur Eliasson's space exhibitions[194] and Jeppe Hein's installations.[195]

Cuisine

The cuisine of Denmark, like that of the other Nordic countries and of Northern Germany, consists mainly of meat and fish. This stems from the country's agricultural past, its geography, and its climate of long, cold winters. With 145.9 kg (321.7 lb) of meat per person consumed in 2002, Denmark has the highest consumption of meat per person of any country in the world.[196]

The open sandwiches, known as smørrebrød, which in their basic form are the usual fare for lunch, can be considered a national speciality when prepared and decorated with a variety of fine ingredients. Hot meals traditionally consist of ground meats, such as frikadeller (meat balls), or of more substantial meat and fish dishes such as flæskesteg (roast pork with crackling) or kogt torsk (poached cod) with mustard sauce and trimmings. In 2014, stegt flæsk was voted the national dish of Denmark. Denmark is known for its Carlsberg and Tuborg beers and for its akvavit and bitters although imported wine is now gaining popularity.