Demographics of the Soviet Union

| ||||||||||||

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Soviet Union | ||||||||||||

|

Leadership |

||||||||||||

|

Governance

|

||||||||||||

|

Judiciary

|

||||||||||||

|

History and politics

|

||||||||||||

|

Society

|

||||||||||||

|

Soviet Union portal | ||||||||||||

According to data from the 1989 Soviet census, the population of the Soviet Union was 70% East Slavs, 12% Turkic peoples, and all other ethnic groups below 10%. Alongside the atheist majority of 60% there were sizable minorities of Russian Orthodox followers (approx. 20%) and Muslims (approx. 15%).

Demographic statistics

The following demographic statistics are from the 1990 edition of the CIA World Factbook,[1] unless otherwise indicated. (Note: The CIA did not include the Baltic states in its statistic calculations.)

Population

- Population: 290,938,469 (July 1990)

Population growth rate

- 0.7% (1990)

Crude birth rate

- 18 births/1,000 population (1990)

Crude death rate

- 10 deaths/1,000 population (1990)

Net migration rate

- 0 migrants/1,000 population (1990)

Infant mortality rate

- 24 deaths/1,000 live births (1990)

Life expectancy at birth

- 65 years male, 74 years female (1990)

Total fertility rate

- 2.4 children born/woman (1990)

Nationality

- noun - Soviet(s); adjective - Soviet

Literacy

- 99.9%

Labor force

Labor force: 152,300,000 civilians; 80% industry and other nonagricultural fields, 20% agriculture; shortage of skilled labor (1989)

Organized labor: 98% of workers are union members; all trade unions are organized within the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (AUCCTU) and conduct their work under guidance of the Communist party

-

Soviet Union population density map 1982

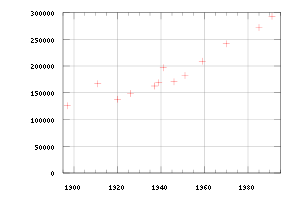

Population

The Russian Empire lost territories with about 30 million inhabitants after the Russian Revolution (Poland 18 mil; Finland 3 mil; Romania 3 mil; the Baltic states 5 mil and Kars to Turkey 400 thous). World War II losses were estimated between 27-30 million, including an increase in infant mortality of 1.3 million. Total war losses include territories annexed by Soviet Union in 1939-45.

Although the population growth rate decreased over time, it remained positive throughout the history of the Soviet Union in all republics, and the population grew each year by more than 2 million except during periods of wartime, collectivisation, and famine.

| Date | Population |

|---|---|

| January 1897 (Russian Empire): | 125,640,000 |

| 1911 (Russian Empire): | 167,003,000 |

| January 1920 (Russian SFSR): | 137,727,000* |

| January 1926 : | 148,656,000[2] |

| January 1937: | 162,500,000[2] |

| January 1939: | 168,524,000[2] |

| June 1941: | 196,716,000[2] |

| January 1946: | 170,548,000[2] |

| January 1951: | 182,321,000[2] |

| January 1959: | 209,035,000[2] |

| January 1970: | 241,720,000[3] |

| 1977: | 257,700,000 |

| July 1982: | 270,000,000 |

| July 1985: | 277,700,000 |

| July 1990: | 290,938,469 |

| July 1991: | 293,047,571 |

Ethnic groups

The Soviet Union was one of the world's most ethnically diverse countries, with more than 100 distinct national ethnicities living within its borders.

| Republic | Population of Republic (000s) 1979 | 1989 | % urban 1979 | Titular nationality (1989) | Russian (1989) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soviet Union | 262,436 | 286,717 | 67 | - | 51.4 |

| Russian SFSR | 137,551 | 147,386 | 74 | 81.3 | 81.3 |

| Ukrainian SSR | 49,755 | 51,704 | 68 | 72.7 | 22.1 |

| Byelorussian SSR | 9,560 | 10,200 | 67 | 77.9 | 13.2 |

| Moldavian SSR | 3,947 | 4,341 | 47 | 64.5 | 13.0 |

| Azerbaijan SSR | 6,028 | 7,029 | 54 | 82.7 | 5.6 |

| Georgian SSR | 5,015 | 5,449 | 57 | 70.1 | 6.3 |

| Armenian SSR | 3,031 | 3,283 | 68 | 93.3 | 1.6 |

| Uzbek SSR | 15,391 | 19,906 | 42 | 71.4 | 8.3 |

| Kazakh SSR | 14,685 | 16,538 | 57 | 39.7 | 37.8 |

| Tajik SSR | 3,801 | 5,112 | 33 | 62.3 | 7.6 |

| Kirghiz SSR | 3,529 | 4,291 | 38 | 52.4 | 21.5 |

| Turkmen SSR | 2,759 | 3,534 | 45 | 72.0 | 9.5 |

| Lithuanian SSR | 3,398 | 3,690 | 68 | 79.6 | 9.4 |

| Latvian SSR | 2,521 | 2,681 | 72 | 52.0 | 34.0 |

| Estonian SSR | 1,466 | 1,573 | 72 | 61.5 | 30.3 |

Other ethnic groups included Abkhaz, Adyghes, Aleuts, Assyrians, Avars, Bashkirs, Bulgarians, Buryats, Chechens, Chinese, Chuvash, Cossacks, Evenks, Finns, Gagauz, Germans, Greeks, Hungarians, Ingushes, Inuit, Jews, Kalmyks, Karakalpaks, Karelians, Kets, Koreans, Lezgins, Maris, Mongols, Mordvins, Nenetses, Ossetians, Poles, Roma, Romanians, Tats, Tatars, Tuvans, Udmurts, and Yakuts.

Religion

The Soviet Union adhered to the doctrine of State atheism from 1928–1941, in which religion was largely discouraged and heavily persecuted, and a secular state from 1945 until its dissolution. However, according to various Soviet and Western sources, over one-third of the country's people professed religious beliefs: Russian Orthodox 20%, Muslim 15%, Protestant, Georgian Orthodox, Armenian Orthodox, and Roman Catholic 7%, Jewish less than 1%, atheist 60% (1990 est.).[1] There were some indigenous pagan belief systems existent in the Siberian and Russian Far Eastern lands in the local populations.

Language

Russian became the official language of the Soviet Union in 1990.[5] Until that time it was still necessary to have a language of common communication. The choice inevitably fell on Russian, which was the native tongue of most Soviet citizens.[6]

Overall there were more than 200 languages and dialects spoken (at least 18 with more than 1 million speakers); Slavic group 75%, other Indo-European 8%, Altaic 12%, Uralian 3%, Caucasian 2% (1990 est.)[1]

Life expectancy and infant mortality

After the October revolution, the life expectancy for all age groups went up. A newborn child in 1926-27 had a life expectancy of 44.4 years, up from 32.3 years thirty years before. In 1958-59 the life expectancy for newborns went up to 68.6 years. This improvement was seen in itself by some as immediate proof that the socialist system was superior to the capitalist system.[7]

The trend continued into the 1960s, when the life expectancy in the Soviet Union went beyond the life expectancy in the United States. The life expectancy in Soviet Union were fairly stable during most years, although in the 1970s went slightly down probably because of alcohol abuse.

The improvement in infant mortality leveled out eventually, and after a while infant mortality began to rise. After 1974 the government stopped publishing statistics on this. This trend can be partly explained by the number of pregnancies went drastically up in the Asian part of the country where infant mortality was highest, while the number of pregnancies was markedly down in the more developed European part of the Soviet Union. For example, the number of births per citizens of Tajikistan went up from 1.92 in 1958-59 to 2.91 in 1979-80, while the number in Latvia was down to 0.91 in 1979-80.[7]

Population dynamics in the 1970s and 1980s

The crude birth rate in the Soviet Union throughout its history had been decreasing - from 44.0 per thousand in 1926 to 18.0 in 1974, mostly due to urbanization and rising average age of marriages. The crude death rate had been gradually decreasing as well - from 23.7 per thousand in 1926 to 8.7 in 1974.[8] While death rates did not differ greatly across regions of the Soviet Union through much of Soviet history, birth rates in southern republics of Transcaucasia and Central Asia were much higher than those in the northern parts of the Soviet Union, and in some cases even increased in the post-World War II period. This was partly due to slower rates of urbanization and traditionally early marriages in southern republics.[8]

As a result mainly of differential birthrates, with most of the European nationalities moving toward sub-replacement fertility and the Central Asian and other nationalities of southern republics having well-above replacement-level fertility, the percentage who were Russians was gradually being reduced. According to some Western scenarios of the 1990s, if the Soviet Union had stayed together it is likely that Russians would have lost their majority status in the 2000s (decade).[9] This differential could not be offset by assimilation of non-Russians by Russians, in part because the nationalities of southern republics maintained a distinct ethnic consciousness and were not easily assimilated.

The late 1960s and the 1970s witnessed a dramatic reversal of the path of declining mortality in the Soviet Union, and was especially notable among men in working ages, and also especially in Russia and other predominantly Slavic areas of the country.[10] While not unique to the Soviet Union (Hungary in particular showed a pattern that was similar to Russia), this male mortality increase, accompanied by a noticeable increase in infant mortality rates in the early 1970s, drew the attention of Western demographers and Sovietologists at the time.[11]

An analysis of the official data from the late 1980s showed that after worsening in the late 1970s and the early 1980s, the situation for adult mortality began to improve again.[12] Referring to data for the two decades ending in 1989-1990, while noting some abatement in adult mortality rates in the Soviet republics in the 1980s, Ward Kingkade and Eduardo Arriaga characterized this situation as follows: "All of the former Soviet countries have followed the universal tendency for mortality to decline as infectious diseases are brought under control while death rates from degenerative diseases rise. What is exceptional in the former Soviet countries and some of their East European neighbors is that a subsequent increase in mortality from causes other than infectious disease has brought about overall rises in mortality from all causes combined. Another distinctive characteristic of the former Soviet case is the presence of unusually high levels of mortality from accidents and other external causes, which are typically associated with alcoholism."[13]

The rising infant mortality rates in the Soviet Union in the 1970s became the subject of much discussion and debate among Western demographers. The infant mortality rate (IMR) had increased from 24.7 in 1970 to 27.9 in 1974. Some researchers regarded the rise in infant mortality as largely real, a consequence of worsening health conditions and services.[14] Others regarded it as largely an artifact of improved reporting of infant deaths, and found the increases to be concentrated in the Central Asian republics where improvement in coverage and reporting of births and deaths might well have the greatest effect on increasing the published rates.[15]

The rising reported adult mortality and infant mortality was not explained or defended by Soviet officials at the time. Instead, they simply stopped publishing all mortality statistics for ten years. Soviet demographers and health specialists remained silent about the mortality increases until the late 1980s when the publication of mortality data resumed and researchers could delve into the real and artifactual aspects of the reported mortality increases. When these researchers began to report their findings, they accepted the increases in adult male mortality as real and focused their research on explaining its causes and finding solutions.[16] In contrast, investigations of the rise in reported infant mortality concluded that while the reported increases in the IMR were largely an artifact of improved reporting of infant deaths in the Central Asian republics, the actual levels in this region were much higher than had yet been reported officially.[17] In this sense the reported rise in infant mortality in the Soviet Union as a whole was an artifact of improved statistical reporting, but reflected the reality of a much higher actual infant mortality level than had previously been recognized in official statistics.

As the detailed data series that was ultimately published in the late 1980s showed, the reported IMR for the Soviet Union as a whole increased from 24.7 in 1970 to a peak of 31.4 in 1976. After that the IMR gradually decreased and by 1989 it had fallen to 22.7, which was lower than had been reported in any previous year (though close to the figure of 22.9 in 1971).[18] In 1989, the IMR ranged from a low of 11.1 in the Latvian SSR to a high of 54.7 in the Turkmen SSR.[19]

Research conducted subsequent to the dissolution of the Soviet Union revealed that the originally reported mortality rates very substantially underestimated the actual rates, especially for infant mortality. This has been shown for Transcaucasian and Central Asian republics.[20][21]

See also

- Demography of Central Asia

- Religion in the Soviet Union

- Family in the Soviet Union

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 CIA Factbook 1990 Retrieved on 2009-04-10

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Andreev, E.M., et al., Naselenie Sovetskogo Soiuza, 1922-1991. Moscow, Nauka, 1993. ISBN 5-02-013479-1

- ↑ Statoids population figures of the Soviet Union Retrieved on 2009-04-10

- ↑ Sakwa, Richard (1998). Soviet Politics in Perspective. London: Routledge. pp. 242–250. ISBN 0-415-07153-4.

- ↑ "ЗАКОН СССР ОТ 24.04.1990 О ЯЗЫКАХ НАРОДОВ СССР" (The April 24, 1990 Soviet Union Law about the Languages of the Soviet Union) (Russian)

- ↑ Bernard Comrie, The Languages of the Soviet Union, page 31, the Press Syndicate of the University of Cambridge, 1981. ISBN 0-521-23230-9

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 The Seeming Paradox of Increasing Mortality in a Highly Industrialized Nation: the Example of the Soviet Union : 1985. author Dinkel, R. H.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Great Soviet Encyclopedia. (in Russian) (3rd ed. ed.). Moscow: Sovetskaya Entsiklopediya. 1977. vol. 24 (part II), p. 15.

- ↑ Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver. 1990. "Growth and Diversity of the Population of the Soviet Union," Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Sciences, No. 510: 155-77.

- ↑ The first to call attention to the reversal of declining adult mortality in the Soviet Union (in contrast to trends in Western Europe) were J. Vallin and J. C. Chesnais, "Recent Developments of Mortality in Europe, English-Speaking Countries and the Soviet Union, 1960-1970," Population 29 (4-5): 861-898. For a probe into the age-specific and regional aspects of the trends, once new mortality tables were released in the late 1980s, see Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver. 1989. "The Changing Shape of Soviet Mortality, 1958-1985: An Evaluation of Old and New Evidence," Population Studies 43: 243-265. Also see Alain Blum and Roland Pressat. 1987. "Une nouvelle table de mortalité pour l'URSS (1984-1985)," Population, 42e Année, No. 6 (Nov.): 843-862.

- ↑ For a summary of the mortality trends and the literature concerning them, see Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver. 1990. "Trends in Mortality of the Soviet Population," Soviet Economy 6, No. 3: 191-251.

- ↑ Michael Ryan, "Life expectancy and mortality data from the Soviet Union," British Medical Journal, Vol. 296, No. 6635 (May 28, 1988): 1,513-1515.

- ↑ W. Ward Kingkade and Eduardo E. Arriaga, “Mortality in the New Independent States: Patterns and Impacts,” in José Luis Bobadilla, Christine A. Costello, and Faith Mitchell, Eds., Premature Death in the New Independent States (Washington, D.C., National Academy Press 1997), 156-183, citation at p. 157.

- ↑ Most notably, see Christopher Davis and Murray Feshbach. 1980. "Rising Infant Mortality in the Soviet Union in the 1970s," U.S. Bureau of the Census, International Population Reports, Series P-95, Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office. The following article, which ostensibly reviewed the Davis and Feshbach report, brought widespread attention to the issue of health care in the Soviet Union: Nick Eberstadt, "The Health Crisis in the Soviet Union," New York Review of Books 28, No. 2 (February 19, 1981).

- ↑ Most notably, see Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver. 1986. "Infant Mortality in the Soviet Union: Regional Differences and Measurement Issues," Population and Development Review 12, No. 4: 705-737, and Barbara A. Anderson and Brian D. Silver, "The Geodemography of Infant Mortality in the Soviet Union, 1950-1990," in G. J. Demko, Z. Zaionchkovskaya, S. Pontius, and G. Ioffe, Eds., Population Under Duress: The Geodemography of Post-Soviet Russia, Westview Press, pp. 73-103 (1999).

- ↑ See, for example, Juris Krumins. 1990. "The Changing Mortality Patterns in Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia: Experience of the Past Three Decades," Paper presented at the International Conference on Health, Morbidity and Mortality by Cause of Death in Europe. December 3–7. Vilnius; A. G. Vishnevskiy, V.M. Shkolnikov, and S.A. Vasin. 1990. "Epidemiological Transition in the Soviet Union as Mirrored by Regional Disparities," Paper presented at the International Conference on Health, Morbidity and Mortality by Cause of Death in Europe. December 3–7. Vilnius; and F. Meslé, V. Shkolnikov, and J. Vallin. 1991. "Mortality by Cause in the Soviet Union in 1970-1987: The Reconstruction of Time Series," Paper presented at the European Population Conference, October 21–25, Paris.

- ↑ See, for example, A. A. Baranov, V. Y. Al‘bitskiy, and Y. M. Komarov. 1990. "Тенденции младенческой смертности в СССР в 70-80е годы [Trends in infant mortality in the Soviet Union in the 70's and 80's]," Советское здравоохранение, 3: 3-37; and Y. M. Andreyev and N. Y. Ksenofontova. 1991. "Оценка достоверности данных о младенческой смертности“ [Assessment of the reliability of data on infant mortality], Вестник статистики, 8: 21-28.

- ↑ Comecon Secretariat, Статистический ежегодник стран-членов Совета экономической взаимопомощи, 1990 [Yearbook of the Member-Countries of Comecon] (Moscow: Finansy i statistika, 1990), and Goskomstat SSSR, Демографический ежегодник СССР 1990 [Demographic Yearbook of the Soviet Union] (Moscow: Finansy i statistika, 1990).

- ↑ See Демографический ежегодник СССР 1990, at p. 382.

- ↑ Géraldine Duthé, Irina Badurashvili, Karine Kuyumjyan, France Meslé, and Jacques Vallin, "Mortality in the Caucasus: An attempt to re-estimate recent mortality trends in Armenia and Georgia," Demographic Research, Vol. 22, art. 23, pp. 691-732 (2010).

- ↑ Michel Guillot, So-jung Lim, Liudmila Torgasheva & Mikhail Denisenko, "Infant mortality in Kyrgyzstan before and after the break-up of the Soviet Union," Population Studies, Vol. 67, No. 3: 335-352 (2013).

General sources

- CIA World Factbook 1991 - most figures, unless attributed to another source.

- J. A. Newth: The 1970 Soviet Census, Soviet Studies vol. 24, issue 2 (October 1972) pp. 200–222. - Population figures from 1897 - 1970.

- The Russian State Archive of the Economy: Soviet Censuses of 1937 and 1939 - Population figures for 1937 and 1939. http://www.library.yale.edu/slavic/census3739.html