Demographic-economic paradox

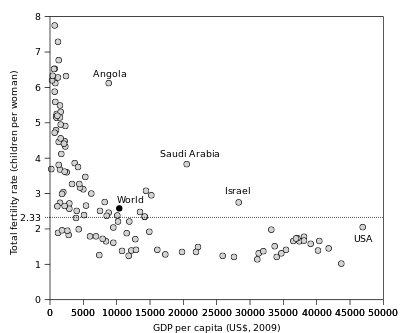

The demographic-economic paradox is the inverse correlation found between wealth and fertility within and between nations. The higher the degree of education and GDP per capita of a human population, subpopulation or social stratum, the fewer children are born in any industrialized country. In a 1974 UN population conference in Bucharest, Karan Singh, a former minister of population in India, illustrated this trend by stating "Development is the best contraceptive."[1]

The term "paradox" comes from the notion that greater means would necessitate the production of more offspring as suggested by the influential Thomas Malthus.[2] Roughly speaking, nations or subpopulations with higher GDP per capita are observed to have fewer children, even though a richer population can support more children. Malthus held that in order to prevent widespread suffering, from famine for example, what he called "moral restraint" (which included abstinence) was required. The demographic-economic paradox suggests that reproductive restraint arises naturally as a consequence of economic progress.

It is hypothesized that the observed trend has come about as a response to increased life expectancy, reduced childhood mortality, improved female literacy and independence, and urbanization that all result from increased GDP per capita,[3] consistent with the demographic transition model.

According to the UN, "[a]mong the 201 countries or areas with at least 90,000 inhabitants in 2013, 50 countries in 1990-1995 and 71 countries in 2005-2010 had below-replacement fertility. In 2005-2010, 27 countries had very low fertility, below 1.5 children per woman, and all of these countries are located in Eastern Asia or Europe." [4]

Demographic transition

.svg.png)

Note the vertical axis is logarithmic and represents millions of people.

Before the 19th century demographic transition of the western world, a minority of children would survive to the age of 20, and life expectancies were short even for those who reached adulthood. For example, in the 17th century in York, England 15% of children were still alive at age 15 and only 10% of children survived to age 20.[3]

Birth rates were correspondingly high, resulting in slow population growth. The second agricultural revolution and improvements in hygiene then brought about dramatic reductions in mortality rates in wealthy industrialized countries, initially without affecting birth rates. In the 20th century, birth rates of industrialized countries began to fall, as societies became accustomed to the higher probability that their children would survive them. Cultural value changes were also contributors, as urbanization and female employment rose.

Since wealth is what drives this demographic transition, it follows that nations that lag behind in wealth also lag behind in this demographic transition. The developing world's equivalent Green Revolution did not begin until the mid-twentieth century. This creates the existing spread in fertility rates as a function of GDP per capita.

Religion

Another contributor to the demographic-economic paradox may be religion. Religious societies tend to have higher birth rates than secular ones, and richer, more educated nations tend to advance secularization.[5] This may help explain the Israeli and Saudi Arabian exceptions, the two notable outliers in the graph of fertility versus GDP per capita at the top of this article. The role of different religions in determining family size is complex. For example, the Catholic countries of southern Europe traditionally had a much higher fertility rate than was the case in Protestant northern Europe. However, economic growth in Spain, Italy, Poland etc., has been accompanied by a particularly sharp fall in the fertility rate, to a level below that of the Protestant north. This suggests that the demographic-economic paradox applies more strongly in Catholic countries, although Catholic fertility started to fall when the liberalizing reforms of Vatican II were implemented. It remains to be seen if the fertility rate among (mostly Catholic) Hispanics in the U.S. will follow a similar pattern.

United States

In his book America Alone: The End of the World as We Know It, Mark Steyn asserts that the United States has higher fertility rates because of its greater economic freedom compared to other industrialized countries. However, the countries with the highest assessed economic freedom, Hong Kong and Singapore, have significantly lower birthrates than the United States. According to the Index of Economic Freedom, Hong Kong is the most economically free country in the world.[6] Hong Kong also has one of the world's lowest birth rates.[7]

Fertility and population density

Studies have also suggested a correlation between population density and fertility rate.[8][9][10] Hong Kong and Singapore have the third and fourth-highest population densities in the world. This may account for their very low birth rates despite high economic freedom. By contrast, the United States ranks 180 out of 241 countries and dependencies by population density.

Consequences

A reduction in fertility can lead to an aging population which leads to a variety of problems, see for example the Demographics of Japan.

A related concern is that high birth rates tend to place a greater burden of child rearing and education on populations already struggling with poverty. Consequently, inequality lowers average education and hampers economic growth.[11] Also, in countries with a high burden of this kind, a reduction in fertility can hamper economic growth as well as the other way around.[12]

Recent scientific criticism

Some scholars have recently questioned the assumption that economic development and fertility are correlated in a simple negative manner. A study published in Nature in 2009 has found that when using the Human Development Index instead of the GDP as measure for economic development, fertility follows a j-shaped curve: with rising economic development, fertility rates indeed do drop at first, but then begin to rise again with even greater levels of social and economic development.[13] [14]

See also

- Advanced maternal age

- Aging of Europe

- Aging of Japan

- Demographic economics

- Fertility and intelligence

- Total fertility rate

References

- ↑ Weil, David N. (2004). Economic Growth. Addison-Wesley. p. 111. ISBN 0-201-68026-2.

- ↑ Malthus, Thomas Robert (1826), An Essay on the Principle of Population (6 ed.), London: John Murray, archived from the original on 28 August 2013

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Montgomery, Keith, The demographic transition, University of Wisconsin-Marathon County, archived from the original on 18 October 2012

- ↑ http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/pdf/fertility/world-fertility-patterns-2013.pdf

- ↑ Blume, Michael; Ramsel, Carsten; Graupner, Sven (June 2006), "Religiousity as a demographic factor - an underestimated connection?" (PDF), Marburg Journal of Religion 11 (1), archived from the original (PDF) on 25 April 2012

- ↑ 2013 Index of Economic Freedom, The Heritage Foundation, 2013, retrieved 25 October 2013

- ↑ The World Factbook – Rank Order – Birth rate, Central Intelligence Agency, archived from the original on 27 September 2013

- ↑ Sato, Yasuhiro (30 July 2006), "Economic geography, fertility and migration", Journal of Urban Economics, retrieved 31 March 2008

- ↑ Pan, Chia-lin (1966), "An Estimate of the Long-Term Crude Birth Rate of the Agricultural Population of China", Demography 3 (1), retrieved 31 March 2008

- ↑ Gattis, Tory (15 January 2006), High-density smart growth = population implosion?, archived from the original on 13 March 2012, retrieved 31 March 2008

- ↑ de la Croix, David and Matthias Doepcke: Inequality and growth: why differential fertility matters. American Economic Review 4 (2003) 1091–1113.

- ↑ UNFPA: Population and poverty. Achieving equity, equality and sustainability. Population and development series no. 8, 2003.

- ↑ "The best of all possible worlds? A link between wealth and breeding". The Economist. August 6, 2009.

- ↑ Mikko Myrskylä; Hans-Peter Kohler; Francesco C. Billari (6 August 2009). "Advances in development reverse fertility declines". Nature 460: 741-743. doi:10.1038/nature0823.

External links

- Macleod, Mairi (29 October 2013), Population paradox: Why richer people have fewer kids (2940), New Scientist