Democratic deficit in the European Union

| European Union |

This article is part of a series on the |

Policies and issues

|

Elections

|

The concept of a democratic deficit within the European Union is the idea that the governance of the European Union in some way lacks democratic legitimacy. The term was initially used to criticise the transfer of legislative powers from national governments to the Council of ministers of the EU. This led to an elected European Parliament being created and given the power to approve or reject EU legislation. Since then, usage of the term has broadened to describe newer issues facing the European Union.

Opinions differ as to whether the European Union has a democratic deficit[1] or how it should be remedied if it exists.[2][3] Proponents of Pro-Europeanism or European unification argue that the European Union should reform its institutions to make them more accountable, while Eurosceptics argue that the European Union should reduce its powers.

Use and meaning of the term

The phrase democratic deficit is cited as first being used by David Marquand in 1979, referring to the then European Economic Community, the forerunner of the European Union. He argued that the European Parliament (then the Assembly) suffered from a democratic deficit as it was not directly elected by the citizens of Europe.[4] 'Democratic deficit' in relation to the European Union, refers to a perceived lack of accessibility to the ordinary citizen, or lack of representation of the ordinary citizen, and lack of accountability of European Union institutions.[5][6]

Constitutional nature of the democratic deficit

In the European Union, there are two sources of democratic legitimacy: the European Parliament, directly elected by the people of the European Union as a whole, and the Council (together with the European Council) representing the peoples of the individual states, the civil service being appointed by the two bodies jointly. Democratic legitimacy within the EU can be compared with the dual legitimacy provided for in a federal polity, like the United States, where there are two independent sources of democratic legitimacy, with decisions being approved both by one institution representing the people as a whole and by a separate body representing the peoples of the individual states.[7]

The democratic deficit has been called a 'structural democratic deficit', in that it is inherent in the construction of the European Union as a supranational union that is neither a pure intergovernmental organisation, nor a true federal state. The Federal Constitutional Court of Germany, for instance, argues that decision-making processes in the EU remain largely those of an international organisation, which would ordinarily be based on the principle of the equality of states. The principle of equality of states and the principle of equality of citizens cannot be reconciled in a Staatenverbund.[2] In other words, in a supranational union or confederation (which is not a federal state) there is a problem of how to reconcile the principle of equality among nation states, which applies to international (intergovernmental) organisations, and the principle of equality among citizens, which applies within nation states.[3] A 2014 report from the British Electoral Reform Society wrote that "This unique institutional structure makes it difficult to apply the usual democratic standards without significant changes of emphasis. Certainly, the principles of representativeness, accountability and democratic engagement are vital, but the protection of the rights of minorities is perhaps especially important. The EU is a political regime that is, in one sense at least, entirely made up of minorities"[8]

European Commission

One criticism of democratic illegitimacy focuses on the role of the European Commission in initiating legislation. This criticism has, in turn, been criticised, using comparisons with the situation in national governments where few members' bills are ever debated and "fewer than 15% are ever successfully adopted in any form", while government proposals "generally pass without substantial or substantive amendments from the legislature".[9] The European Commission is appointed every five years after approval by the Council of Ministers and the European Pariament.[10] This is the principal democratic illegitimacy of the EU executive.

According to R. Daniel Kelemen, fragmented power systems like the European Union and the United States may tend to produce more detailed regulations that give member states less discretion in implementation.[11]

Voting in the Council is usually by qualified majority voting, and sometimes unanimity is required. This means that for the vast majority of EU legislation the corresponding national government has usually voted in favour in the Council. To give an example, up to September 2006, out of the 86 pieces of legislation adopted in that year the government of the United Kingdom had voted in favour of the legislation 84 times, abstained from voting twice and never voted against.[12]

In an attempt to strengthen democratic legitimacy, the Lisbon Treaty provided that the nomination of the President of the European Commission should "take account" of the result of the European parliamentary elections, interpreted by the larger parliamentary groups to mean that the European Council should nominate the candidate (Spitzenkandidat) proposed by the dominant parliamentary group. However, this has also been criticized from the point of view of democratic legitimacy on the grounds that the European Union is not a country and the European Commission is not a government, also having a semi-judicial role that requires it to act as a "referee" or "policeman" rather than a partisan actor. The fear is that a "semi-elected" Commission president might be "too partisan to retain the trust of national leaders; too powerless to win the loyalty of citizens". This, too, is seen as a possibly insoluble problem resulting from the European's dual nature, partly an international organization and partly a federation.[13]

The Electoral Reform Society observed polling evidence from Germany which showed that support for the CDU/CSU (EPP group) ahead of the 2014 European Parliament elections was higher than support for the Social Democrats (S&D group) and that there was little difference between their support in the opinion polls for national and European Parliament elections. This was despite another poll showing that S&D candidate Martin Schulz was more popular among German voters than EPP candidate Jean-Claude Juncker. They concluded that "[t]his does not suggest that the majority of German voters are treating the contest as a chance to choose a Commission President." However, they recommended that the candidate model be kept with "a clearer set of rules for future elections."[8]

European Parliament

One criticism of democratic illegitimacy focuses on the alleged weakness of the European Parliament. This has been countered by a number of political scientists, who have compared the systems of governance in the European Union with that of the United States, and stated that the alleged powerless or dysfunctional nature of the European Parliament is now a "myth".[9] It is argued that there are important differences from national European parliaments, such as the role of committees, bipartisan voting, decentralized political parties, executive-legislative divide and absence of Government-opposition divide. All these traits are considered as signs of weakness or unaccountability, but these very same traits are found in the US House of Representatives to a lesser or greater degree, the European Parliament is more appropriately compared with the US House of Representatives.[9] In that sense, it is now a powerful parliament, as it is not controlled by a "governing majority": majorities have to be built afresh for each item of legislation by explanation, persuasion and negotiation.

Legislative initiative in the EU rests solely with the commission, while in member states it is shared between parliament and executive; however less than 15% of legislative initiatives from MEPs become law when they do not have the backing of the executive. The European Parliament can only propose amendments, but unlike in national parliaments, the executive has no guaranteed majority to secure the passage of its legislation. In national parliaments, amendments are usually proposed by the opposition, who lack a majority for their approval and usually fail. But given the European Parliament's independence, and the need to obtain majority approval from it, proposals made by its many parties (none of which hold a majority alone) have an unusually high 80% success rate in the adoption of its amendments. Even in controversial proposals, its success rate is 30%, something not mirrored by national legislatures.[9]

Liberal Democrat (ELDR) MEP Chris Davies, says he has far more influence as a member of the European Parliament than he did as an opposition MP in the House of Commons. "Here I started to have an impact on day one", "And there has not been a month since when words I tabled did not end up in legislation."[14]

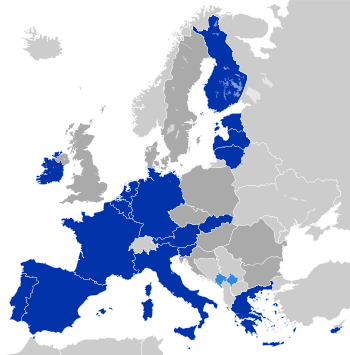

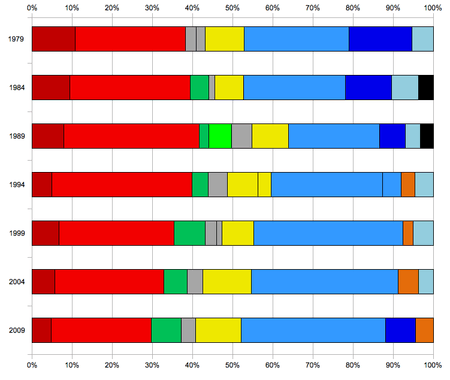

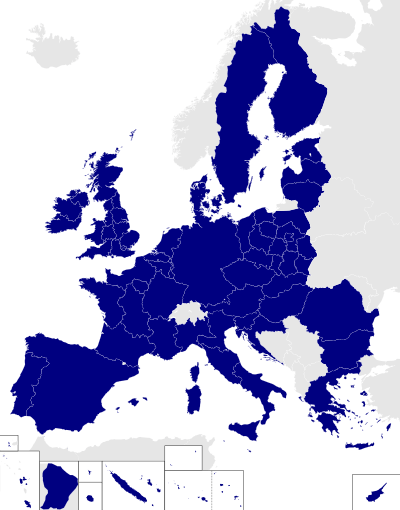

European elections

The low turnout at European elections has been cited as weakening the democratic legitimacy of the European Parliament: the BBC commented that in Britain many more votes were cast in an election on the reality show Big Brother than in the 1999 European Parliament election. On the other hand, the President of the European Parliament compared the turnout for the European Parliament to the presidential elections in the United States:

| “ | Turnout across Europe (1999) was higher than in the last US presidential election, and I don't hear people questioning the legitimacy of the presidency of the United States | ” |

In fact,the figures that are compared, the European Parliament voter turnout from 1999 (49.51%)[15] and the US presidential voter turnout from 1996 (49%)[16] are only marginally different, and the US voter turnout for 1996 was the lowest turnout in the US since 1924 (when it was 48.9%). The turnout in European elections has also been declining every election without exception to a low of 42.54% in 2014.[17]

According to one observer, the EU democratic deficit can be viewed as having a formal component (which is likely to be remedied) but also a social component resulting from people's low acceptance of the EU, as evidenced by low voter turnout.[18]

Legal commentators such as Schmidt and Follesdal argue that the European Union lacks politics that individual citizens understand. This flows from the lack of knowledge of political parties and is reinforced by the lack of votes at European Union elections.

Development of democratic legitimacy and transparency

Over time, a number of constitutional changes have been introduced to increase democratic legitimacy:

- The Maastricht Treaty introduced

- the status of EU citizenship, granting EU citizens the right to vote and stand in elections to the European Parliament and municipal elections in their country of residence, irrespective of their nationality (subject to age and residency qualifications).[19]

- the legislative procedure known as the "co-decision procedure", giving the directly elected European Parliament the right of "co-deciding" legislation on an equal footing with the Council of the European Union.[19]

- The Treaty of Lisbon, which came into force on 1 December 2009 introduced

- a separate treaty title confirming that the functioning of the EU shall be founded on representative democracy and giving EU citizens both direct representation through the European Parliament and indirect representation via national governments through the Council of the European Union[20]

- the establishment of the co-decision procedure as the standard ("ordinary") legislative procedure[20]

- a significant increase in the powers of the European Parliament[20]

- Any EU citizen or resident now has the right to petition the European Parliament "on any matter which comes within the Union's field of activity and which affects him, her, or it directly".[Article 227 TFEU].[21]

- Meetings of the Council are now public when there is a general debate and when a proposal for a legislative act is voted on. These debates can be viewed[22] in real time on the Internet.[23]

- The Lisbon Treaty enhanced the role of national parliaments in EU legislation.[24]

- With the Treaty of Lisbon, the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union, which was solemnly proclaimed by the European Parliament, the Council of the European Union and the European Commission in the year 2000 was given full legal effect.[25]

See also

References

- ↑ The Myth of Europe's Democratic Deficit, Princeton University

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Press release no. 72/2009. Judgment of 30 June 2009" (Press release). German Federal Constitutional Court – Press office. 30 June 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

The extent of the Union's freedom of action has steadily and considerably increased, not least by the Treaty of Lisbon, so that meanwhile in some fields of policy, the European Union has a shape that corresponds to that of a federal state, i.e. is analogous to that of a state. In contrast, the internal decision-making and appointment procedures remain predominantly committed to the pattern of an international organisation, i.e. are analogous to international law; as before, the structure of the European Union essentially follows the principle of the equality of states. [. . .] Due to this structural democratic deficit, which cannot be resolved in a Staatenverbund, further steps of integration that go beyond the status quo may undermine neither the States’ political power of action nor the principle of conferral. The peoples of the Member States are the holders of the constituent power. [. . .] The constitutional identity is an inalienable element of the democratic self-determination of a people.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Pernice, Ingolf; Katharina Pistor (2004). "Institutional settlements for an enlarged European Union". In George A. Bermann and Katharina Pistor. Law and governance in an enlarged European Union: essays in European law. Hart Publishing. pp. 3–38. ISBN 978-1-84113-426-0.

Among the most difficult challenges has been reconciling the two faces of equality – equality of states versus equality of citizens. In an international organization [. . .] the principle of equality of states would ordinarily prevail. However, the Union is of a different nature, having developed into a fully fledged 'supranational Union', a polity sui generis. But to the extent that such a polity is based upon the will of, and is constituted by, its citizens, democratic principles require that all citizens have equal rights.

- ↑ Marquand, David (1979). Parliament for Europe. Cape. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-224-01716-9.

The resulting 'democratic deficit' would not be acceptable in a Community committed to democratic principles.

Chalmers, Damian et al. (2006). European Union law: text and materials. Cambridge University Press. p. 64. ISBN 978-0-521-52741-5.'Democratic deficit' is a term coined in 1979 by the British political scientist . . . David Marquand .

Meny, Yves (2003). "De La Democratie En Europe: Old Concepts and New Challenges". Journal of Common Market Studies 41: 1–13. doi:10.1111/1468-5965.t01-1-00408.Since David Marquand coined his famous phrase 'democratic deficit' to describe the functioning of the European Community, the debate has raged about the extent and content of this deficit.

- ↑ "Glossary: Democratic deficit". European Commission. Retrieved 2009-08-06.

The democratic deficit is a concept invoked principally in the argument that the European Union and its various bodies suffer from a lack of democracy and seem inaccessible to the ordinary citizen because their method of operating is so complex. The view is that the Community institutional set-up is dominated by an institution combining legislative and government powers (the Council of the European Union) and an institution that lacks democratic legitimacy (the European Commission).

- ↑ Chryssochoou, Dimitris N. (007). "Democracy and the European polity". In Michelle Cini. European Union politics (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press, 2007. p. 360. ISBN 978-0-19-928195-4. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ Schütze, Robert (2012). European Constitutional Law. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–77. ISBN 9780521732758.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Electoral Reform Society — Close the Gap — Tackling Europe's democratic deficit.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 Kreppel, Amie (2006). "Understanding the European Parliament from a Federalist Perspective: The Legislatures of the USA and EU Compared" (PDF). Center for European Studies, University of Florida. Retrieved 2008-09-26.

- ↑ http://ec.europa.eu/about/index_en.htm

- ↑ Kelemen, R. Daniel (2012). The Rules of Federalism: Institutions and Regulatory Politics in the EU and Beyond. Harvard University Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-674-01309-4.

- ↑ http://www.consilium.europa.eu/cms3_fo/showPage.asp?id=1279&lang=EN

- ↑ "A democratic nightmare: Seeking to confront the rise of Eurosceptics and fill the democratic deficit". The Economist''. Retrieved 3 October 2014.|date=26 October 2013|

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 "The EU's democratic challenge". BBC News. 21 November 2003. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ↑ http://www.ukpolitical.info/european-parliament-election-turnout.htm

- ↑ Voter turnout in the United States presidential elections

- ↑ http://www.euractiv.com/sections/eu-elections-2014/its-official-last-eu-election-had-lowest-ever-turnout-307773

- ↑ Avbelj, Matej. "Can the New European Constitution Remedy the EU 'Democratic Deficit'?". Open Society Institute. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009.

In its formal character, the democratic deficit is measured according to the ideal of a formal legitimacy which corresponds to legality understood in the sense that democratic institutions and processes created the law on which they are based and comply with. In its social character, the democratic deficit strives for a social legitimacy that connotes a broad, empirically determined social acceptance of the system.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Schütze, Robert (2012). European Constitutional Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 31–32. ISBN 978-0-521-73275-8.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Schütze, Robert (2012). European Constitutional Law. Cambridge University Press. pp. 43–44. ISBN 978-0-521-73275-8.

- ↑ Schütze, Robert (2012). European Constitutional Law. Cambridge University Press. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-521-73275-8.

- ↑ video.consilium.europa.eu

- ↑ "The Council of the European Union)".

- ↑ "IPEX Interparliamentary EU Information Exchange )" (PDF).

- ↑ Craig, Paul; Grainne De Burca; P. P. Craig (2007). "Chapter 11 Human rights in the EU". EU Law: Text, Cases and Materials (4th ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 379. ISBN 978-0-19-927389-8.

Further reading

- Corbett, Richard; Jacobs, Francis; Shackleton, Michael (2011), 'The European Parliament' (8 ed.), London: John Harper Publishing, ISBN 978-0-9564508-5-2

- Follesdal, A and Hix, S. (2005) ‘Why there is a democratic deficit in the EU‘ European Governance Papers (EUROGOV) No. C-05-02

- Kelemen, Dr. R. Daniel; (2004) ‘The Rules of Federalism: Institutions and Regulatory Politics in the EU and Beyond‘ Harvard University Press

- Majone, G. (2005) 'Dilemmas of European Integration'.

- Marsh, M. (1998) ‘Testing the second-order election model after four European elections’ British Journal of Political Science Research. Vol 32.

- Moravcsik, A. (2002) ‘In defence of the democratic deficit: reassessing legitimacy in the European Union’ Journal of Common Market Studies. Vol 40, Issue 4.

- Reif, K and Schmitt, S. (1980) ‘Nine second-order national elections: a conceptual framework for the analysis of European election results’ European Journal of Political Research. Vol 8, Issue 1.