Demetrios Palaiologos

| Demetrios Palaiologos | |

|---|---|

| Despot of the Morea | |

| Reign | 1436–1460 |

| Predecessor | Constantine Palaiologos |

| Wives |

|

| Issue | Helena Palaiologina |

| Dynasty | Palaiologos |

| Father | Manuel II Palaiologos |

| Mother | Helena Dragaš |

| Born | 1407 |

| Died | May 12, 1470 (aged 62) |

| Signature |

[[File: |

Demetrios Palaiologos or Demetrius Palaeologus (Greek: Δημήτριος Παλαιολόγος, Dēmētrios Palaiologos; 1407–1470), Despot in the Morea de facto 1436–1438 and 1451–1460 and de jure 1438–1451, previously governor of Lemnos 1422–1440, and of Mesembria 1440–1451. He would have been the legitimate claimant to the Byzantine throne after 1453, until his desertion to the Ottomans in 1460.

Life

Demetrios Palaiologos was a younger son of the Byzantine Emperor Manuel II Palaiologos and his wife Helena Dragaš. His maternal grandfather was Constantine Dragaš. His brothers included emperors John VIII Palaiologos and Constantine XI Palaiologos, as well as Theodore II Palaiologos and Thomas Palaiologos, rulers of the Despotate of Morea, and Andronikos Palaiologos, despot in Thessalonica.

As a younger son Demetrios was not expected to rule, but was granted the court title of despot in accordance with standard practice. His ambition apparently led to conflict in the imperial family. Although he then received possession of the island of Lemnos from his father Emperor Manuel II in 1422, he refused to live there and fled to the court of King Sigismund of Hungary in 1423, requesting protection against his brothers. More than a year passed until he moved to Lemnos, in 1425, where he lived in peace for the next decade.

Perhaps too untrustworthy to leave behind, he was part of the entourage of his brother Emperor John VIII Palaiologos, arriving in Ferrara for the Council of Basel-Ferrara-Florence in 1437, which sought to reunite the Roman Catholic Church and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Opposed to the union, Demetrios left for home in 1439 before the conclusion of the council in Florence, leaving the emperor behind.

Forced to surrender Lemnos as penalty for returning home without the Emperor's consent, Demetrios was compensated with a more distant appanage at Mesembria on the Black Sea in 1440. Accordingly, in 1442 he made an alliance with the Ottoman Turks, who lent him military support and besieged Constantinople, demanding that Demetrios be given control of the more strategic appanage of Selymbria, nearer the capital.[1] This effort failed, and the appanage of Selymbria was turned over first to Constantine Palaiologos and then to Theodore II Palaiologos.

On October 31, 1448, John VIII died, while his designated heir Constantine was in the Morea. Exploiting his location nearer Constantinople, Demetrios tried to stage a coup d'état and secure the throne for himself. His attempt failed, mostly due to the intervention of their mother, Helena Dragaš. In 1449, the new Emperor Constantine XI gave Demetrios half of the Morea in order to remove him from the vicinity of Constantinople.

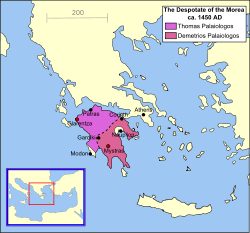

After the fall of Constantinople to the forces of Mehmed II of the Ottoman Empire on May 29, 1453, the Morea remained the last surviving remnant of the Byzantine Empire. The fall of the capital became a sign for the last members of Kantakouzenos family to try take power from the Palaiologoi in this last free province, and Demetrios I Kantakouzenos's grandchild Manuel began a revolt. The following year the forces of the Palaiologos brothers, with Ottoman aid, destroyed the rebel forces. Not long after this victory, civil war erupted between Demetrios and his younger brother Thomas, who had ruled in the Morea alongside Constantine from 1428. As Thomas was threatening to dislodge Demetrios, the latter called on the Ottoman Sultan Mehmed II for support, and surrendered Mistra in 1460.

After the Turks chased out Thomas and his family (who escaped to Italy), Mehmed II refused to return the Morea to Demetrios, of whom the Sultan commented that "he is not man enough to rule any country". He was allowed to spend his life at the palace of Adrianople and was granted the taxes collected from the islands of Imbros, Lemnos, Samothrace and Thasos.

Demetrios lived in honorary captivity until falling out of favor with Mehmed II in 1467. He was then exiled to Didymoteicho until 1469, when he was recalled to court but fell sick during the following year. He briefly became a monk under the name "David" before dying in 1470. His wife Theodora died a few weeks later.

Family

Demetrios Palaiologos was married first to Zoe Paraspondyle (March 1436)[2] and then to Theodora Asanina, daughter of Paul (Paulos) Asanes (16 April 1441)[3] By his second wife he had at least one daughter:

- Helena Palaiologina (died before 1470)[4] was taken into the Sultan's harem.[5]

Ancestry

| Ancestors of Demetrios Palaiologos | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Demetrios Palaiologos Palaiologos dynasty Born: 1407 Died: 1470 | ||

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Constantine Palaiologos |

Despot of the Morea 1451–1460 with Thomas Palaiologos |

Succeeded by Office abolished Claimants in exile |

| Titles in pretence | ||

| Preceded by Constantine XI Palaiologos |

— TITULAR — Byzantine Emperor (formally "Emperor of Constantinople") 1453–1460 with Thomas Palaiologos Reason for succession failure: The Fall of Constantinople led to the Ottoman conquest of the Byzantine Empire |

Succeeded by Thomas Palaiologos |

References

- ↑ George Sphrantzes, 25, 1-3; translated in Marios Phillipides, The Fall of the Byzantine Empire: A Chronicle by George Sphrantzes, 1401-1477 (Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 1980), p. 53

- ↑ Sphrantzes, 22.6; Phillipides, The Fall of the Byzantine Empire, p. 48

- ↑ Sphrantzes, 24.9; Phillipides, The Fall of the Byzantine Empire, p. 52

- ↑ Nicol, Donald MacGillivray (1992). The immortal emperor: the life and legend of Constantine Palaiologos, last emperor of the Romans. Cambridge [England]: Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 0-521-89409-3.

- ↑ Karpat, Kemal H. (2002). Studies on Ottoman Social and Political History: Selected Articles and Essays (Social, Economic and Political Studies of the Middle East and Asia). Brill Academic Publishers. pp. 597, 598. ISBN 90-04-12101-3.

Bibliography

- Oxford Dictionary of Byzantium, Oxford University Press, 1991.

- Joseph Freiherr von Hammer-Purgstall, Geschichte des Osmanischen Reiches

- Nea Domi (Νέα Δομή), vol. 26, article: Helena Palaeologus (Ελένη Παλαιολόγου)