Delphi Archaeological Museum

| Delphi Archaeological museum | |

|---|---|

| Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Δελφών | |

|

Delphi Archaeological Museum | |

Location within Greece | |

| Established | 1903 |

| Location | Τ.Κ. 33054, Delphi, Greece |

| Coordinates | 38°28′48″N 22°29′59″E / 38.4801°N 22.4997°E |

| Type | Archaeological museum |

| Collections | Greek antiquities |

| Visitors | 137,550 (2009)[1] |

| Owner | Greek Ministry of Culture (10th ephorate of prehistoric and classical antiquities |

| Website | Outline on the website of the Greek Ministry of Culture |

Delphi Archaeological museum (Modern Greek : Αρχαιολογικό Μουσείο Δελφών) is one of the principal museums of Greece and one of the most visited. It is operated by the Greek Ministry of Culture (10th ephorate of prehistoric and classical antiquities). Founded in 1903, it has been re-arranged multiple times and houses the discoveries made at the panhellenic sanctuary of Delphi, which date from the prehistoric period through to late Antiquity.

Organised in fourteen rooms on two levels, the museum mainly displays statues, including the famous Charioteer of Delphi; architectural elements, like the frieze of the Siphnian Treasury; and offerings made to the sanctuary of Pythian Apollo, like the Sphinx of Naxos. The exhibition floor space is more than 2270m2, while the storage and conservation rooms (mosaics, ceramics and metals) take up 558m2. Visitors are also catered to by an entrance hall, a cafeteria and a gift shop.[2]

is the museum that houses the ancient artifacts that were found in Delphi, Greece. Its centerpiece are the antiquities found in the complex of the ancient Oracle of Delphi from the 18th century BC when the oracle was founded to its decline in Late Antiquity. Its exhibits are mainly offerings to the oracle and architectural parts of the buildings.

History of the museum

First museum

A first, small museum was inaugurated on 2 May 1903 to celebrate the end of the first great campaign of French excavations and to hold the discoveries. The building was designed by the French architect Albert Tournaire, financed by the Greek banker and philanthropist Andreas Syngros and built in the location where it remains to this day, although it has since been entirely transformed. Two wings framed a small central building. The arrangement of the collection, entrusted to the leader of the archaeological expedition, Théophile Homolle, was rudimentary. The guides asserted its aesthetic value, but visitors claimed likened it to a warehouse. Either way, it lacked any chronological or thematic arrangement. The quality of the exhibits themselves were meant to be enough. The novel factor was the focus on the restoration of the principle monuments of the site with plaster, in order to display the discoveries in a more accessible way.[3]

Renovations

In the 1930s, although the museum had achieved undeniable success with the international public, it was becoming too small to hold the new discoveries on the site or the increasing number of tourists.[2] In addition, its arrangement (or absence of arrangement) and the plaster restorations were increasingly criticised. Finally, its appearance was criticised as a little too "French" in a period which insisted on "Greekness." In 1935, the construction of a new building was begun. It took three years. The new museum was, like its predecessor, representative of the architectural fashion of its time. The work, including a new arrangement of the objects by the Professor of Archaeology at Thessaloniki, Constantinos Romalos, was completed in 1939. The reorganisation of the Archaic collections was entrusted to the Frenchman Pierre de La Coste-Messelière, who determined the new arrangement, without the plaster restorations of significant artefacts, including that of the Siphnian Treasury, which had become the principle attraction. The antiquities were presented in a chronological fashion, catalogued and labelled.[4]

However, this arrangement was only briefly in use. The antiquities were put into storage at the beginning of the Second World War. Part was kept at Delphi in the ancient Roman tombs or in specially dug pits in front of the museum. The most precious objects (the chryselephantine objects, the silver Statue of a Bull discovered three months before the outbreak of war and the Charioteer) were sent to Athens in order to be stored in the vaults of the Bank of Greece. They remained there for ten years. The charioteer was on display in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens until 1951. The region of Delphi was at the heart of the combat zone in the Greek civil war and the museum was not reopened until 1952. For six years, visitors could view the arrangement that had been envisioned in 1939. However, very quickly, the museum proved insufficient and it was necessary to undertake a new phase of construction, completed in 1958.[5]

The renovation of the museum was entrusted to the architect Patroklos Karatinos and the archaeologist Christos Karouzos was sent from the National Archaeological Museum of Athens to rearrange the collection, under the supervision of the ephor of Delphi, Ioanna Constantinou. Karatinos created two new exhibition halls and modified the structure to allow in more natural light. The arrangement of the collection remained chronological, but a greater focus was placed on the sculpture, with statues increasingly separated from their architectural contexts. The museum reopened its doors in 1961.[6] The museum became one of the most visited tourist attractions in Greece: in 1998, it received more than 300,200 visitors, almost as much as the National Archaeological Museum of Athens in the same period (325,000 visitors).[1][6]

Current Museum

Between 1999 and 2003, the museum underwent yet another phase of renovations, carried out by the Greek architect Alexandros Tombazis. Thes renovations included a new facade in a contemporary style and a new hall for the charioteer. The rest of the museum was modernised and adjusted to facilitate the circulation of visitors. A new lobby, a cafeteria and a gift shop with replicas of the antiquities were also created.[2] The collection was rearranged in order to reconcile the need to display the main attractions of the museum effectively and the wish to present the latest theories and discoveries of ancient Greek history. They also attempted to redeem neglected objects, like the classical facade of the Temple of Apollo. The museum opened its doors once more for its centenary.[7]

Collections

The collections of the Delphi Archaeological Museum are arranged chronologically in fourteen rooms.

Rooms 1 & 2

The first two rooms are devoted to the most ancient objects. The first room presents bronze votive offerings, dating to the 8th and 7th centuries BC, including shields and tripods. The second room includes most of the kouroi (archaic male statues).[8]

-

Head of a Griffon (bronze)

-

Bronze votive shield

-

Daedelic style kouros, bronze

-

Torso of a kouros

Room 3

Room 3 is dominated by the Parian marble statues known as Cleobis and Biton, which were produced at Argos between 610 and 580 BC. It also contains the metopes of the Sicyonian Treasury.[9]

-

Cleobis and Biton

Room 4

This is dedicated to the very precious offerings found in an offering pit on the Sacred Way: the silver Statue of a Bull and the chryselephantine statues.[9]

-

Chryselephantine objects.

-

Chryselephantine objects.

Room 5

This room displays the Sphinx of Naxos and the friezes of the Siphnian Treasury.[10]

-

Part of one of the friezes of the Siphnian Treasury

-

East pediment of the Siphnian Treasury

-

caryatid from the Siphnian Treasury

Room 6

This room contains the archaic and classical facades of the Temple of Apollo.[11]

Rooms 7 & 8

These two rooms contain objects from the Treasury of the Athenians; the first room contains the metopes, the second contains acroteria, pedimental sculpture and inscriptions.[12]

-

Metope of the Treasury of the Athenians

-

Metope of the Treasury of the Athenians

Rooms 9 & 10

The objects in these two rooms come from the sanctuary of Athena Pronoia.[12]

Room 11

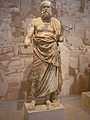

The room contains Late Classical and early Hellenistic objects, among which the Dancers of Delphi, the dedication of Daochos, and the Omphalos stand out.[12]

-

Statue of Agias of Pharsala, possibly by Lysippos or his son Euthykrates, part of the dedication of Daochos

-

Dedication of Daochos

Room 12

Room 12 contains Late Hellenistic and Roman objects, including a famous statue of Antinous.[12]

-

Bust of the Roman consul Titus Quinctius Flamininus

-

Head of a philosopher, said to be Plutarch

Room 13

This is the room of the Charioteer.[13]

-

Charioteer of Delphi, bronze, beginning of the 5th century BC

Room 14

This last room is devoted to the final years of the sanctuary.[13]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 General Secretariat of the National Statistical Service

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Museum, outline on the website of the Greek Ministry of Culture

- ↑ (Colonia 2006, p. 17)

- ↑ (Colonia 2006, p. 18 et 24)

- ↑ (Colonia 2006, p. 24-25)

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (Colonia 2006, p. 25)

- ↑ (Colonia 2006, p. 15 et 25)

- ↑ Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 411 & 414.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 415.

- ↑ Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 414-415.

- ↑ Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 415-416.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 12.3 Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 416.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Grèce continentale. Guide bleu., p. 417.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Archaeological Museum of Delphi. |