Death of Freddie Gray

|

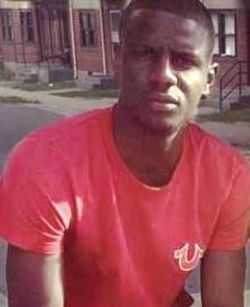

Freddie Carlos Gray, Jr. August 16, 1989 – April 19, 2015 | |

| Date | Incident on April 12, 2015 |

|---|---|

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland, U.S. |

| Type | Death while in police custody |

| Cause | Spinal cord injury |

| Filmed by | Two witnesses to Gray's arrest |

| Participants | Freddie C. Gray, six Baltimore police officers |

| Outcome | Death of Freddie Gray on April 19, 2015 |

| Burial | April 27, 2015 |

| Inquiries |

|

| Accused | Caesar R. Goodson Jr., William G. Porter, Brian W. Rice, Edward M. Nero, Garrett Miller, Alicia D. White[1] |

| Charges |

Goodson: Second-degree murder Others: involuntary manslaughter, second-degree assault, manslaughter by vehicle, misconduct in office, false imprisonment[1] |

On April 12, 2015, Freddie Gray, a 25-year-old African-American man, was taken into custody by the Baltimore Police Department for allegedly possessing a switchblade; however, Baltimore state's attorney Marilyn J. Mosby subsequently stated "The knife was not a switchblade and is lawful under Maryland law".[2] While being transported in a police van, Gray fell into a coma and was taken to a trauma center.[3][4] Gray died on April 19, 2015. His death was ascribed to injuries to his spinal cord.[4] On April 21, 2015, pending an investigation of the incident, six Baltimore police officers were temporarily suspended with pay.[3]

The circumstances of the injuries were initially unclear; eyewitness accounts suggested that the officers involved had partaken in unnecessary use of force against Gray while arresting him—a claim denied by an officer involved.[3][4][5] Commissioner Anthony Batts reported that the officers did not buckle him inside the van when being transported to the police station—a report supported by a medical investigation which found that Gray had sustained the injuries while in transport.[6][7]

On May 1, 2015, Baltimore prosecutors ruled that Gray's death was a homicide, and that his arrest was illegal because the alleged switchblade was a legal-sized pocket knife. The prosecutors stated that they had probable cause to file criminal charges against the six police officers who were believed to be involved in his death.[2] One officer was charged with second degree depraved-heart murder, and others were charged with crimes ranging from manslaughter to illegal arrest.[2]

Gray's death resulted in an ongoing series of protests and civil disorder, in the spirit of the reaction to the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown. A major protest in downtown Baltimore on April 25, 2015, turned violent, resulting in 34 arrests and injuries to 15 police officers.[8] After Gray's funeral on April 27, civil unrest intensified with looting and burning of local businesses and a CVS drug store, culminating with a state of emergency declaration by Governor Larry Hogan and Maryland National Guard deployment to Baltimore.

Background

Freddie C. Gray was the 25-year-old son of Gloria Darden. He had a twin sister, Fredericka, as well as another sister, Carolina.[9] At the time of his death, Gray lived in the home owned by his sisters in the Gilmor Homes neighborhood.[9] He stood 5 feet 8 inches (1.73 m) and weighed 145 pounds (66 kg).[10]

Gray had a criminal record, mainly for misdemeanors and drug-related offenses.[10] Gray had been involved in 20 criminal court cases, five of which were still active at the time of his death, and was due in court on a possession charge on April 24.[11][10]

Arrest and death

Police encountered Freddie Gray on the morning of April 12, 2015,[5] in the street near Baltimore’s Gilmor Homes housing project,[12] an area known to have high levels of home foreclosures, poverty, drug deals and violent crimes. According to the charging documents submitted by the Baltimore police,[13] At around 8:45 A.M., the police "made eye contact" with Gray,[12] who proceeded to flee on foot "unprovoked upon noticing police presence", was apprehended after a brief foot chase, and was taken into custody without the use of force or incident. During the arrest, the officer stated that he "noticed a knife clipped to the inside of his front right pocket ...The knife was recovered by this officer and found to be a spring assisted one hand operated knife." [5][14] The formal charge filed by Officer Garrett Miller accused Gray of violating statute 19 59 22 - "unlawfully carry, possess, and sell a knife commonly known as a switchblade knife, with an automatic spring or other device for opening and/or closing the blade within the limits of Baltimore City." This was found to be false during the investigation, as the knife was of folding type which is not illegal.[15]

Two bystanders captured Gray's arrest with video recordings, showing Gray, apparently in pain, being dragged into a police van by officers. A bystander with connections to Gray stated that the officers were previously "folding" Gray—with one officer bending Gray's legs backwards, and another holding Gray down by pressing a knee into Gray's neck, subsequent to which most witnesses contemporaneously commented that he "couldn't walk" [16], "can't use his legs" [17], and "his leg look broke and you all dragging him like that"[18] Another witness told the Baltimore Sun that they had witnessed Gray being beaten with batons.[5][19]

According to the police timeline, Gray was placed in a transport van within 11 minutes of his arrest, and within 30 minutes, paramedics were summoned to take Gray to a hospital.[20] The van made four confirmed stops while Gray was detained. At 8:46 a.m., Gray was unloaded in order to be placed in leg irons because police said he was "irate." A later stop, recorded by a private security camera, shows the van stopped at a grocery store. At 8:59 a.m., a second prisoner was placed in the vehicle while officers checked on Gray's condition. In the official police report, officer Miller stated that “during transport to Western District via wagon transport, the defendant suffered a medical emergency and was immediately transported to Shock Trauma via Medic.”[21] [5][22]He was taken to the University of Maryland R Adams Cowley Shock Trauma Center in a coma.[23]

The media has suggested the possibility of a so-called "rough ride"—where a handcuffed prisoner is placed without a seatbelt in an erratically driven vehicle—as a contributing factor in Gray's injury.[24][25]

In the following week, according to the Gray family attorney, Gray suffered from total cardiopulmonary arrest at least once but was resuscitated without ever regaining consciousness. He remained in a coma, and underwent extensive surgery in an effort to save his life.[26] According to his family, he lapsed into a coma with three fractured vertebrae, injuries to his "voice box", and his spine "80% severed" at his neck. Police confirmed that the spinal injury led to Gray’s death.[3][4] The attorney also disputed the claim that Gray had been in possession of a switchblade, and stated that it was actually a "pocketknife of legal size".[27] He died on April 19, 2015, a week after his arrest.[14]

Aftermath

Investigation

The Baltimore Police Department suspended six officers with pay pending an investigation of Gray's death.[14] The six officers involved in the arrest were identified as Lieutenant Brian Rice, 41 (18 years on the force), Sergeant Alicia White, 30 (5 years on the force), Officer William Porter, 25 (5 years on the force), Officer Garrett Miller, 26 (3 years on the force), Officer Edward Nero, 29 (3 years on force), and Officer Caesar Goodson, 45 (16 years on the force).[28] On April 24, 2015, Police Commissioner Anthony Batts said, "We know our police employees failed to get him medical attention in a timely manner multiple times."[6] Batts also acknowledged police did not follow procedure when they failed to buckle Gray in the van while he was being transported to the police station.[6] The U.S. Department of Justice also opened an investigation into the case.[29]

On April 30, 2015, Kevin Moore, the man who filmed Gray's arrest, was arrested at gunpoint following "harassment and intimidation" by police. Moore stated to have cooperated with police and gave over his video of Gray's arrest for investigation. He claimed, despite aiding in the investigation, his photo was made public by police for further questioning.[30] Moore was later released from custody, but two other individuals who were arrested along with Moore remained in custody.[31] The same day, medical examiners reported Gray sustained more injuries as a result of him slamming into the inside of the transport van, "apparently breaking his neck; a head injury he sustained matches a bolt in the back of the van". [7]

Charges

On May 1, 2015, the Baltimore State's Attorney's office ruled that Freddie Gray's death was a homicide, and that they had probable cause to file criminal charges against the six officers involved. Marilyn Mosby, the state's attorney for Baltimore City, said that the Baltimore police had acted illegally and that "No crime had been committed" (by Freddie Gray).[32] Mosby said that Gray "suffered a critical neck injury as a result of being handcuffed, shackled by his feet and unrestrained inside the BPD wagon."[33][34] Mosby said officers had "failed to establish probable cause for Mr. Gray’s arrest, as no crime had been committed,”[35] and charged officers with false imprisonment, because Gray was carrying a pocket knife of legal size, and not the switchblade police claimed he had possessed at the time of his arrest.[15]

Three of the officers are facing manslaughter charges and one faces an additional count of second degree depraved-heart murder. The murder charge carries a possible penalty of 30 years in prison; the manslaughter and assault offenses carry a maximum penalty of 10 years in prison. [36]

- Officer Caesar R. Goodson, Jr.: Second degree depraved heart murder; involuntary manslaughter; second-degree assault; manslaughter by vehicle (gross negligence); manslaughter by vehicle (criminal negligence); misconduct in office[36]

- Officer William G. Porter: Involuntary manslaughter; second degree assault; misconduct in office[36]

- Lt. Brian W. Rice: Involuntary manslaughter; two counts of second degree assault; manslaughter by vehicle (gross negligence); two counts of misconduct in office; false imprisonment[36]

- Officer Edward M. Nero: Two counts of second degree assault; manslaughter by vehicle (gross negligence); two counts of misconduct in office; false imprisonment[36]

- Officer Garrett E. Miller: Two counts of second degree assault; two counts of misconduct in office; false imprisonment[36]

- Sgt. Alicia D. White: Involuntary manslaughter; second degree assault; misconduct [36]

As of May 1, all six officers were in custody.[37]

Response to charges

Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake said there was no place in the Baltimore Police department for those police officers who "choose to engage in violence, brutality, racism and brutality.[35] Gene Ryan, president of the police union chapter said that despite the tragic situation, "none of the officers involved are responsible for the death of Mr. Gray."[35]

Public response

Public reaction to the death has drawn parallels to the response to the 2014 shooting of Michael Brown, as part of a larger string of controversial uses of force by police officers in the United States—especially against African-Americans.[15][38][39] As of April 30, 2015, 22 demonstrations had been held nationwide in direct response to Gray's death or in solidarity with Baltimore.[40]

On April 18, 2015, hundreds of people participated in a protest outside the Baltimore Police Department.[41] Three days later, on April 21, 2015, according to Reuters, "[h]undreds of demonstrators gathered in Baltimore", protesting Gray's death.[19] The next day, Gene Ryan, the president of the local lodge of the Fraternal Order of Police, expressed sympathy for the Gray family, but criticized the "rhetoric of protests" and suggested that "the images seen on television look and sound much like a lynch mob." William Murphy, attorney for the Gray family, demanded an "immediate apology and a retraction".[42] Ryan defended his statement two days later, while admitting that the wording was poor.[43] Charles M. Blow of The New York Times, reminded of a column he wrote several years ago, said that comparing protests to lynch mobs was too extreme because it inflames racial tensions by belittling the significance of the history of lynching in the United States.[44]

On April 25, 2015, protests were organized in downtown Baltimore, and the protests turned violent as protesters threw rocks and set fires.[45] At least 34 people were arrested, and 15 officers were injured.[8][46][47] On April 27, rioting and looting began after the funeral of Gray,[48] with two patrol cars destroyed and 15 officers reported injured.[8] Protesters looted and burned down a CVS Pharmacy location in downtown Baltimore.[49]

In reaction to the unrest, the Maryland State Police sent 82 troopers to protect the city.[50] A Baltimore Orioles baseball game against the Chicago White Sox scheduled for the evening was postponed due to the unrest.[51] The next game commenced as scheduled but, as a precautionary measure, fans were barred from attending.[52] Maryland Governor Larry Hogan declared a state of emergency, and activated the Maryland National Guard.[53][54] Hogan also activated 500 state troopers for duty in Baltimore and requested an additional 5,000 police officers from other locales.[55][56]

At a press conference, Baltimore's mayor announced there would be a citywide curfew from 10:00 p.m. to 5:00 a.m.[57][58][59] School trips were canceled until mid-May,[60][61] and Baltimore's city schools were closed on April 28.[62] In addition, both the University of Maryland campus in downtown Baltimore and the Mondawmin Mall were closed early.[63]

Protests outside Baltimore also took place in other U.S. cities. In New York City, 143 people at Union Square were arrested on April 29, 2015 for blocking traffic and refusing to relocate. On the same day, outside the White House in Washington, D.C., nearly 500 protesters converged without an incident. In Denver, eleven people were arrested as protesters were involved in physical altercations with officers. Other protests in response to Gray's death took place in cities including Philadelphia, Minneapolis, and Portland.[64]

See also

- Death of Eric Garner

- List of cases of police brutality in the United States

- List of killings by law enforcement officers in the United States, April 2015

- List of riots

- Police brutality in the United States

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Gordon, Kalani (2015-05-01). "The charges". Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Blinder, Alan (May 1, 2015). "Prosecutors Charge 6 Baltimore Officers in Freddie Gray Death". New York Times. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Laughland, Oliver; Swaine, Jon (April 20, 2015). "Six Baltimore officers suspended over police-van death of Freddie Gray". The Guardian. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Graham, David A. (April 22, 2015). "The Mysterious Death of Freddie Gray". Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Rector, Kevin. "The 45-minute mystery of Freddie Gray's death". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Payne, Ed; Almasy, Steve; Pearson, Michael (April 24, 2015). "Police: Freddie Gray didn't get timely medical care after arrest". CNN. Retrieved April 24, 2015.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 "Report: Freddie Gray sustained injury in back of police van". CNN.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Bacon, John (April 27, 2015). "Baltimore police, protesters clash; 15 officers hurt". USA Today. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Marbella, Jean (April 23, 2015). "Beginning of Freddie Gray's life as sad as its end, court case shows". Retrieved April 23, 2015.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 Muskal, Michael (April 22, 2015). "The death of Freddie Gray: What we know - and don't know". Los Angeles Times (in en-US). ISSN 0458-3035. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ "What we know, don't know about Freddie Gray's death". CNN.com. 22 April 2015. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Freddie Gray’s Death Becomes a Murder Case". The New Yorker. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "Charging documents for Freddie Gray". Baltimore Sun. Tribune Publishing. 2015-04-28. Retrieved 2015-04-30.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 McLaughlin, Eliott (April 21, 2015). "Freddie Gray death: Protesters rally in Baltimore". CNN.com. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 "Freddie Gray: Baltimore police to face criminal charges". BBC News. 1 May 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "Freddie Gray witness speaks to Anderson Cooper". CNN. CNN. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- ↑ "New video shows arrest of Freddie Gray in Baltimore". CNN. CNN. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

- ↑ "Baltimore police drag Freddie Gray". Daily Mail. Daily Mail accessdate=2015-05-01.

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Simpson, Ian (April 21, 2015). "Crowds protest death of man after arrest by Baltimore police". Reuters. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ "The Timeline of Freddie Gray’s Arrest and the Charges Filed". NYTimes.com. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Events Leading to Freddie Gray's Death". nydailynews.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Peralta, Eyder (April 20, 2015). "Baltimore Police Promise Full Investigation Into Man's Death After Arrest". NPR. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ Bever, Lindsey; Ohlheiser, Abby (April 20, 2015). "Baltimore police: Freddie Gray died from a 'tragic injury to his spinal cord'". The Washington Post (in en-US). ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved April 26, 2015.

- ↑ Donovan, Doug; Puente, Mark (April 23, 2015). "Freddie Gray not the first to come out of Baltimore police van with serious injuries". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Broom, Scott. "Baltimore police prisoner rough ride history". WUSA 9. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ McLaughlin, Eliott C.; Brumfield, Ben; Ford (April 20, 2015). "Baltimore looks into Freddie Gray police custody death". CNN. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ "Arresting officers provide statements in Freddie Gray death". CNN.com. April 22, 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ Miller, Jayne. 6 officers suspended in Freddie Gray case, WBAL, April 20, 2015. Retrieved on April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Boswell, Craig (April 21, 2015). "Feds investigating Baltimore man's death in police custody". www.cbsnews.com. Retrieved April 22, 2015.

- ↑ "The Man Who Filmed Freddie Gray Video has been Arrested at Gunpoint". independent.co.uk. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Kevin Moore: Five Facts You Need to Know". heavy.com. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ Jon Swaine; Oliver Laughland; Raya Jalabi (1 May 2015). "Freddie Gray death: cries of 'justice' in Baltimore after six officers charged". The Guardian. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "6 Baltimore Police Officers Charged in Freddie Gray Death". Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ "Six Baltimore police officers face murder, other charges in death of black man". Reuters.com. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Alan Blinder and Richard Perez-Pena (1 May 2015). "6 Baltimore Police Officers Charged in Freddie Gray Death". NY Times. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 36.4 36.5 36.6 "Charges Against Officers In Freddie Gray's Death Range From Murder To Assault". npr.org. Retrieved May 1, 2015.

- ↑ "Six officers charged in death of Freddie Gray". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- ↑ Swift, Tim. "Baltimore's dual identity explains unrest". BBC News. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (27 April 2015). "Baltimore Enlists National Guard and a Curfew to Fight Riots and Looting". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- ↑ "At least 857 Black Lives Matter demonstrations have been held in the last 286 days". Elephrame. Elephrame. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Fenton, Justin (18 April 2015). "Hundreds at Baltimore police station protest over man's injuries during arrest". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 30 April 2015.

- ↑ Baltimore Sun (April 22, 2015). "Baltimore police union president likens protests to 'lynch mob'". baltimoresun.com. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ "Police Union Chief Defends Calling Baltimore Protesters A 'Lynch Mob'". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Blow, Charles M. (April 27, 2015). "‘Lynch Mob’: Misuse of Language". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

“Lynch mob” is the same ghastly rhetorical overreach that is often bandied about in political discussions — including in this column I wrote seven years ago. It was a too-extreme comparison then, and it’s a too-extreme comparison now.

- ↑ Stolberg, Sheryl Grey (August 27, 2015). "National Guard Activated in Baltimore as Police and Youths Clash After Funeral for Freddie Gray". New York Times. Retrieved April 28, 2015.

- ↑ Marquez, Miguel; Almasy, Steve (April 25, 2015). "Freddie Gray death: 12 arrested during protests - CNN.com". CNN. Retrieved April 25, 2015.

- ↑ Wenger, Yvonne; Campbell, Colin. City leader calls for peace after 35 arrested, 6 officers injured, Baltimore Sun, April 26, 2015.

- ↑ "Freddie Gray’s Funeral Draws Thousands in Baltimore". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Ford, Dana (April 27, 2015). "Baltimore protests turn violent; police injured - CNN.com". CNN.com. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Gov. declares state of emergency; activates National Guard". WBAL-TV.

- ↑ "Tonight's Orioles game postponed amid violence downtown". Baltimore Sun. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Mayor Stephanie Rawlings Blake Defends Barring Fans". abcnews.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

- ↑ Shapiro, Emily (April 27, 2015). "Maryland Gov. Declares State of Emergency After Violent Clashes in Baltimore". ABC News. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Governor Larry Hogan Signs Executive Order Declaring State Of Emergency, Activating National Guard" (PDF). Government of Maryland. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ matthewhaybrown (April 27, 2015). "Maryland State Police activating 500 officers for Baltimore; requesting up to 5,000 from neighboring states" (Tweet).

- ↑ "Riots erupt across West Baltimore, downtown". The Baltimore Sun.

- ↑ Muskal, Michael; Hennigan, W.J. (April 27, 2015). "Baltimore mayor orders curfew; 'thugs' trying to tear down city, she says". latimes.com. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Al Jazeera and The Associated Press (April 27, 2015). "Violent clashes flare in Baltimore after Freddie Gray funeral | Al Jazeera America". america.aljazeera.com. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "Baltimore Mayor Imposes Curfew, Says 'Thugs' Trying To Tear Down City". CBS Baltimore. Associated Press. April 27, 2015. Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- ↑ "Gov. declares state of emergency; activates National Guard". WBAL-TV. Hearst Television. April 27, 2015. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Staff, WMAR. "Concerns over violence leads to area closings in Baltimore". WMAR. The E.W. Scripps Company. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ Bacon, John; Welch, William M. (April 27, 2015). "Baltimore police, protesters clash; 15 officers hurt". USA Today. Gannett Company. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

Police said more than two dozen people were arrested. The city's schools were canceled for Tuesday.

- ↑ Stolberg, Sheryl Gay (April 27, 2015). "National Guard Called Out in Baltimore as Police and Youths Clash After Funeral for Freddie Gray". The New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- ↑ "In Philadelphia, Supporters of Baltimore Protests take to the Streets". cnn.com. Retrieved April 30, 2015.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||