Dean & Son

.jpg)

Dean & Son was a 19th-century London publishing firm, best known for making and mass-producing moveable children's books and toy books, established around 1800.[1] Thomas Dean founded the firm, probably in the late 1790s, bringing to it innovative lithographic printing processes. By the time his son George became a partner in 1847,[2] the firm was the preeminent publisher of novelty children's books in London.[1] The firm was first located on Threadneedle Street early in the century; it moved to Ludgate Hill in the middle of the century, and then to Fleet Street from 1871 to 1890.[3] In the mid-20th century the firm published books by Enid Blyton.[2]

Dean & Son were one of the first firms to introduce pop-up books for children—which they were able to publish in large numbers. In the 1860s they invented "living picture" books, "animated" by pulling a tab and moving the pictures. Their "pantomime books" were books where the scenes changed in the pictures, created by the use of different page sizes.[1] The books were characterized by engraved illustrations (using technology developed in Germany in the 1790) that were then lavishly hand-coloured.[1] By the end of the 1850s they published more than 200 titles, each book of equal size, each costing sixpence.[2]

The books' subject matter varied, from fairy tales, to stories about anthropomorphized animals, to well-known stories such as Robinson Crusoe.[1] Generally, the books were meant to entertain rather than to be didactic or provide instruction, although some of their books, such as Dean's Moveable Dogs Party, showed upper class Victorian class divisions and taught social mores.[4]

The books were expensive to make: they were printed on letterpress, then hand-coloured in "pouchoir" stencil method, and most likely printed in limited editions.[4] Nevertheless, the firm was the first to bring to the mass market moving picture books,[1] having up to 50 titles of moveable books in print by the latter half of the 19th century, making them leading publisher of these books.[4]

Children found the moveable books entertaining and were induced to play with the clever mechanisms,[4] Various innovative types of mechanisms were designed in Dean's workshops. "Peep show" style consisted of cutting out sections of illustrated scenes, stacking and then folding flat. Turning the page caused the attaching ribbon be pulled and a three-dimensional scene popped up. "Living pictures" were animated by pulling a tab to move or "animate" different parts of the scene on the page. "Pantomime books" were made with pages of varying sizes; turning a page caused the scene to change. These were released in the "Home Pantomime Toy Book" series that included sumptuously coloured and illustrated chromolithographs, and became popular editions, such as their printing of "Beauty and the Beast".[1]

The pricing varied from simple toy books that sold for sixpence to elaborately quarto sized coloured moving books that sold for 5 shillings, with the most of titles selling for 1 shilling, sixpence. Many of their books were sold in a series with names such as the "Royal Picture Toy Books", (priced at 1 shilling, sixpence), Aunt Fanny's "Pictures to Amuse with Tales to Please" series, (priced at 5 shillings),[5] the "Miss Mary Merryheart" series,[6] and their popular "New Scenic Series" introduced in the mid-1850s.[1]

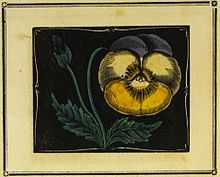

Moveable pictures gallery

-

Folded illustration showing Cinderella trying on the shoe

-

The picture shows Cinderella with the Prince when refolded

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 University of North Texas Library University of Texas Libraries. Retrieved January 24, 2013

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Carpenter, Humphrey, and Mari Prichard. (1984). The Oxford Companion to Children's Literature. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-211582-0, 143

- ↑ "Historical Children's Literature Collection". University of Washington Libraries. Retrieved January 24, 2013

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 University of Virginia Retrieved January 24, 2013.

- ↑ The Publisher's Circular and General Record of British and Foreign Literature, Vol. 42, Dec. 1879, Samson Low. 723.

- ↑ "The Collection of the Lilly Library". Indiana University, Bloomington Illinois. Retrieved January 24, 2013.