De Bruijn graph

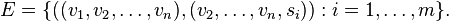

In graph theory, an n-dimensional De Bruijn graph of m symbols is a directed graph representing overlaps between sequences of symbols. It has mn vertices, consisting of all possible length-n sequences of the given symbols; the same symbol may appear multiple times in a sequence. If we have the set of m symbols  then the set of vertices is:

then the set of vertices is:

If one of the vertices can be expressed as another vertex by shifting all its symbols by one place to the left and adding a new symbol at the end of this vertex, then the latter has a directed edge to the former vertex. Thus the set of arcs (aka directed edges) is

Although De Bruijn graphs are named after Nicolaas Govert de Bruijn, they were discovered independently by both De Bruijn[1] and I. J. Good.[2] Much earlier, Camille Flye Sainte-Marie[3] implicitly used their properties.

Properties

- If

then the condition for any two vertices forming an edge holds vacuously, and hence all the vertices are connected forming a total of

then the condition for any two vertices forming an edge holds vacuously, and hence all the vertices are connected forming a total of  edges.

edges. - Each vertex has exactly

incoming and

incoming and  outgoing edges.

outgoing edges. - Each

-dimensional De Bruijn graph is the line digraph of the

-dimensional De Bruijn graph is the line digraph of the  -dimensional De Bruijn graph with the same set of symbols.[4]

-dimensional De Bruijn graph with the same set of symbols.[4] - Each De Bruijn graph is Eulerian and Hamiltonian. The Euler cycles and Hamiltonian cycles of these graphs (equivalent to each other via the line graph construction) are De Bruijn sequences.

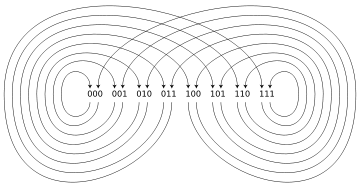

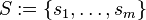

The line graph construction of the three smallest binary De Bruijn graphs is depicted below. As can be seen in the illustration, each vertex of the  -dimensional De Bruijn graph corresponds to an edge of the

-dimensional De Bruijn graph corresponds to an edge of the  -dimensional De Bruijn graph, and each edge in the

-dimensional De Bruijn graph, and each edge in the  -dimensional De Bruijn graph corresponds to a two-edge path in the

-dimensional De Bruijn graph corresponds to a two-edge path in the  -dimensional De Bruijn graph.

-dimensional De Bruijn graph.

Dynamical systems

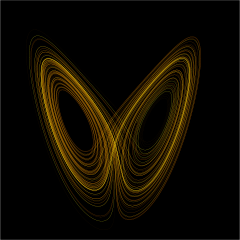

Binary De Bruijn graphs can be drawn (below, left) in such a way that they resemble objects from the theory of dynamical systems, such as the Lorenz attractor (below, right):

This analogy can be made rigorous: the n-dimensional m-symbol De Bruijn graph is a model of the Bernoulli map

The Bernoulli map (also called the 2x mod 1 map for m = 2) is an ergodic dynamical system, which can be understood to be a single shift of a m-adic number.[5] The trajectories of this dynamical system correspond to walks in the De Bruijn graph, where the correspondence is given by mapping each real x in the interval [0,1) to the vertex corresponding to the first n digits in the base-m representation of x. Equivalently, walks in the De Bruijn graph correspond to trajectories in a one-sided subshift of finite type.

Uses

- Some grid network topologies are De Bruijn graphs.

- The distributed hash table protocol Koorde uses a De Bruijn graph.

- In bioinformatics, De Bruijn graphs are used for de novo assembly of (short) read sequences into a genome.[6][7][8][9]

See also

References

- ↑ de Bruijn, N. G. (1946). "A Combinatorial Problem". Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie v. Wetenschappen 49: 758–764.

- ↑ Good, I. J. (1946). "Normal recurring decimals". Journal of the London Mathematical Society 21 (3): 167–169. doi:10.1112/jlms/s1-21.3.167.

- ↑ Flye Sainte-Marie, C. (1894). "Question 48". L'Intermédiaire Math. 1: 107–110.

- ↑ Zhang, Fu Ji; Lin, Guo Ning (1987). "On the de Bruijn-Good graphs". Acta Math. Sinica 30 (2): 195–205.

- ↑ Leroux, Philippe (2002), Coassociative grammar, periodic orbits and quantum random walk over Z, arXiv:quant-ph/0209100, Bibcode:2002quant.ph..9100P

- ↑ Pevzner, Pavel A.; Tang, Haixu; Waterman, Michael S. (2001). "An Eulerian path approach to DNA fragment assembly". PNAS 98 (17): 9748–9753. Bibcode:2001PNAS...98.9748P. doi:10.1073/pnas.171285098. PMC 55524. PMID 11504945.

- ↑ Pevzner, Pavel A.; Tang, Haixu (2001). "Fragment Assembly with Double-Barreled Data". Bioinformatics/ISMB 1: 1–9.

- ↑ Zerbino, Daniel R.; Birney, Ewan (2008). "Velvet: algorithms for de novo short read assembly using de Bruijn graphs". Genome Research 18 (5): 821–829. doi:10.1101/gr.074492.107. PMC 2336801. PMID 18349386.

- ↑ Chikhi, Limasset, Jackman, Simpson, Medvedev (2014). "On the representation of de Bruijn graphs". RECOMB.