Dave Gallaher

| |||

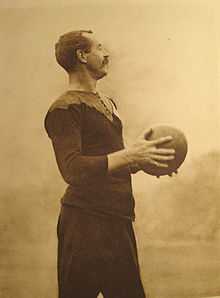

| Gallaher in 1905 during the Original All Blacks' tour. | |||

| Full name | David Gallaher | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date of birth | 30 October 1873 | ||

| Place of birth | Ramelton, County Donegal, Ireland | ||

| Date of death | 4 October 1917 (aged 43) | ||

| Place of death | Passchendaele, Belgium | ||

| Height | 1.83 m (6 ft 0 in) | ||

| Weight | 84 kg (13.2 st) | ||

| School | Katikati School | ||

| Occupation(s) | Freezing works foreman, soldier[1] | ||

| Rugby union career | |||

| Playing career | |||

| Position | hooker, wing-forward | ||

| New Zealand No. | 97 | ||

| Amateur clubs | |||

| Years | Club / team | ||

| 1896–1909 | Ponsonby | ||

| Provincial/State sides | |||

| Years | Club / team | Caps | (points) |

|

|

||

| National team(s) | |||

| Years | Club / team | Caps | (points) |

| 1903–06 | New Zealand | 36 | (14) |

| Coaching career | |||

| Years | Club / team | ||

| |||

| Rugby union career | |||

| Dave Gallaher | |

|---|---|

| Buried at | Nine Elms British Cemetery, Belgium |

| Allegiance | British Crown |

| Service/branch | New Zealand Army |

| Years of service | 1901–02, 1916–17 |

| Rank | Sergeant |

| Service number | 32513[3] |

| Unit |

|

| Memorials | |

David "Dave" Gallaher (born David Gallagher, 30 October 1873 – 4 October 1917) was a New Zealand rugby union footballer best known as the captain of the first New Zealand national team to tour the British Isles – now known as the Original All Blacks. Under his leadership the Originals lost only one of their 35 matches, a narrow and controversial loss to Wales. Gallaher also played in New Zealand's first ever Test match, contested against Australia at Sydney in 1903. The next year he played in their second ever Test – against the touring British Isles team in Wellington. After touring with the Original All Blacks in 1905–06, he retired as a player and took up coaching and selecting, and was a selector for both Auckland and New Zealand for most of the following decade. He worked at a freezing works for most of his adult life apart from in 1901 and 1902 when he served with the New Zealand Contingent in the Anglo-Boer War. In 1916 he enlisted with the New Zealand Division for service in the First World War, and was killed at Passchendaele the following year.

Gallaher was born in Ramelton, Ireland, but emigrated to New Zealand with his family as a child. After moving to Auckland, he initially played rugby for the Parnell club, but in 1895 joined Ponsonby RFC. He was first selected to represent Auckland in 1896, and after returning from fighting in South Africa in August 1902, he continued to play for both Ponsonby and his province. He was first selected for New Zealand for their tour of Australia in 1903. After playing against the touring British Isles team for both New Zealand and Auckland in 1904, he was selected to captain the historic tour of the British Isles, France, and North America the following year. Although his appointment was not universally endorsed, he led his side to 34 wins from 35 matches, where they scored 976 points and conceded only 59. The team received an enthusiastic reception on their return to New Zealand, but Gallaher was widely criticised for his role as wing-forward by the British press, who felt that he deliberately obstructed opponents. His leadership qualities were widely praised, and he co-wrote with vice-captain Billy Stead The Complete Rugby Footballer – a book on rugby tactics and play considered a classic. He married Nellie Francis in 1906, and in 1908 they had their only child, daughter Nora.

Although Gallaher's Originals helped cement rugby as New Zealand's national sport, his role as wing-forward contributed to a strained relationship between the rugby authorities of New Zealand and the Home Nations. A number of memorials exist in Gallaher's honour, including the Gallaher Shield for the winner of Auckland's club championship, the Dave Gallaher Trophy contested between the national teams of France and New Zealand, the Dave Gallaher Memorial Park near his birthplace in Ireland, and a statue of him outside Eden Park in Auckland. He has been inducted into the IRB Hall of Fame, International Rugby Hall of Fame, and New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame.

Early life

David Gallagher, born at Ramelton, County Donegal, Ireland, on 30 October 1873, was the third son of James Henry Gallagher, a 69-year-old shopkeeper, and his wife, 29-year-old Maria Hardy Gallagher (née McCloskie).[4][5] James was a widower who had married Maria a year after the death of his first wife. James had two children from his first marriage, and David was the seventh from his marriage to Maria. The couple had three more children after David, but of their ten offspring, three died in infancy. The couple's other offspring were: Joseph (1867), Isabella (1868), James (1869), Maria (called Molly, 1870), Jane (1871), Thomas (1872), William (1875), Oswald (1876), and James Patrick (1878).[4][lower-alpha 1] David was baptised in the First Ramelton Meeting House on 8 January 1874.[5]

After the struggling in his drapery business in Ramelton, James decided to emigrate with his family to New Zealand as part of George Vesey Stewart's Katikati Special Settlement scheme.[6] In May 1878 the Gallaghers – minus the sick James Patrick who at eight weeks old was too weak to make the trip[lower-alpha 2] – sailed from Belfast on the Lady Jocelyn for Katikati in the Bay of Plenty.[8][9] On arriving in New Zealand, the family altered their name from Gallagher to Gallaher to avoid confusion over spelling and pronunciation.[9]

The Gallaher couple and their six children arrived in Auckland after a three-month voyage,[10] and from there sailed to Tauranga in the Bay of Plenty, before their final voyage to Katikati.[11] On arrival they found the settlement scheme was not what they had envisaged or been promised:[12] the land allocated to the family required enormous work to be broken in before being suitable for farming,[13] there was no easy access to water,[14] and the settlement was very hilly.[15] It had been hoped that James would be employed as the agent for the Donegal Knitting Company in New Zealand, which was to be established by Lord George Augusta Hill. But Hill died unexpectedly and his successor did not support the initiative.[16][17] As the family's poor quality land was insufficient to make a living, the children's mother Maria soon became the chief breadwinner after she obtained a position teaching for £2 a week at the new No. 2 School.[7]

In January 1886 David spent a week in Auckland hospital undergoing surgery to treat stunted muscles in his left leg which had led to curvature of his spine.[18] His mother became sick that same year, and in 1887 lost her teaching position. His mother's condition worsened and she died of cancer on 9 September 1887.[19] With his father in his seventies, in order to assist his brothers in supporting the family, David left school at 13 and took a job working for a local stock and station agent. The older children worked to keep the family together and avoid the younger ones being put up for adoption.[20]

In 1889, with the exception of William who remained in Katikati, the family moved to join Joseph in Auckland where he had found work.[21] David – who was by now 17 years old – was able to obtain work at the Northern Roller Mills Company,[22] and was soon a member of the firm's junior cricket team.[23] In the late 1890s Gallaher took employment at the Auckland Farmers' Freezing Company as a labourer,[24] and had risen to the position of foreman by the time of his deployment for the First World War.[8] His work required the constant handling of heavy animal carcasses, which built up his upper body strength and kept him fit.[24]

Early rugby career

Gallaher first gained attention for his talents as a rugby player while living in Katikati.[5] After moving to Auckland he played junior rugby for the Parnell club from 1890,[25][26] but after the family moved to Freemans Bay following the marriage of his brother Joseph to Nell Burchell,[25] he joined the Ponsonby District Rugby Football Club in 1895.[27] Gallaher, who played at hooker, was selected for an Auckland 'B' side that year, and made his debut for the Auckland provincial side against the touring Queensland team on 8 August 1896.[28] The Aucklanders won 15–6,[28] and Gallaher went on to play in Auckland's remaining fixtures that season; defeats to Wellington, Taranaki and Otago.[29]

In 1897 Gallaher's Ponsonby club won eight of their nine matches, and also the Auckland club championship. He was selected to play for Auckland against the New Zealand representative side that had just completed a tour of Australia. The Aucklanders won 11–10 after scoring a late try;[30] it was only New Zealand's second loss of their eleven-match tour.[31] Later Gallaher was selected for Auckland's three-match tour where they defeated Taranaki, Wellington and Wanganui.[32] Wellington's defeat was their first loss at home since the formation of the Wellington Rugby Football Union.[33] The following season was less eventful for Gallaher, he played much of the season for Ponsonby, but injury prevented his selection for Auckland.[34]

After missing the 1898 season for Auckland, Gallaher continued to be selected for his province throughout 1899 and 1900. The side was undefeated over this time, with him playing for them twice in 1899, and in all four matches in 1900.[35] He represented his province a total of 26 times over his career.[8]

Anglo-Boer War

In January 1901 Gallaher enlisted with the Sixth New Zealand Contingent of Mounted Rifles for service in the Anglo-Boer War. When enlisting he put his birthday as 31 October 1876, back nearly three years.[36] Gallaher was given a send-off by his Ponsonby club before the contingent departed from Auckland on 31 January.[37] After arriving in East London on 14 March 1901,[38] Gallaher's contingent immediately embarked for Pretoria,[39] and it was there that, under the command of General Herbert Plumer,[40] they set about their task of "rid[ding] the Northern Transvaal of Boer guerrillas and sympathizers".[41]

A member of the contingent's 16th (Auckland) Company,[42] he served as a scout of the advanced guard[36] – who rode ahead of their column to look for threats.[43] In October 1901 Gallaher contracted malaria, and was hospitalised in Charlestown. In a letter he composed to his sister while recovering he wrote:

.. we have been all over S[outh] Africa pretty well I believe, on the trek the whole time and it looks as if we will be trekking till the end of the Chapter. We have a fair share of the fighting all the time and I am still alive and kicking although I have had a couple of pretty close calls, one day I thought I would have to say good bye to old New Zealand but I had my usual luck and so came out all right[44]— Dave Gallaher, Letter to his sister Molly, 18 October 1901

Between late December and early January Gallaher and his Contingent were involved in a number of skirmishes.[45] He described one incident where he had several enemies in his sights, but did not have "the heart"[46] to fire at them as they were rescuing their comrade.[47] Writing about a later encounter in a letter to his sister Gallaher wrote: "We had a total of 22 killed and 36 injured and a few taken prisoners it was a pretty mournful sight to see the Red Cross bearers cruising around the field fetching all the dead and wounded who were laying all over the place".[48] By March 1902 he had reached the rank of squadron sergeant-major,[36] and his contingent was travelling to Durban.[49] From there they departed to New Zealand,[49] but Gallaher remained in South Africa and transferred to the Tenth New Zealand Contingent. His new unit did not see active service,[50] and he returned with them to New Zealand in August 1902.[36] For his service Gallaher received the Queen's South Africa Medal (Cape Colony, Orange Free State, and Transvaal Clasps), and King's South Africa Medal (South Africa 1901 and South Africa 1902 Clasps).[51]

Resumption of his rugby career

During his time in South Africa Gallaher did play some rugby,[51] including captaining the New Zealand military team that played ten games and won the rugby championship among the English and Colonial forces.[35] But he was not fit enough to play immediately upon his return to New Zealand,[52] and so did not resume playing rugby for Ponsonby until the 1903 season.[51] When he did return for his club, for the first match of the year, he was described as "the outstanding forward" of the game – in comprehensive defeat of Parnell.[51]

Despite having missed two seasons of provincial rugby, Gallaher was nominated for selection in a New Zealand team to tour Australia. He was duly chosen for the 22-man squad, and became the first ever All Black – as New Zealand representative players are called – from Ponsonby.[53] According to rugby journalist Winston McCarthy (writing in 1968): "The 1903 New Zealand team to Australia is still regarded by old-timers as the greatest team to ever leave New Zealand".[54] However the tour did not start well, a preliminary match against Wellington was lost 14–5,[55] although Gallaher did score his first ever try for New Zealand.[56]

Gallaher played eight matches – the first four as hooker and the remainder as wing-forward[lower-alpha 3][57] – out of eleven during the six week tour. The party was captained by veteran Otago player Jimmy Duncan, who was known as a master tactician.[58] The first match in Australia was against New South Wales, and won comfortable 12–0 by the New Zealanders, despite them having a man sent off.[59] After playing a Combined Western Districts side, a second match was played against New South Wales. This was again won, but only by the narrow margin of 3–0; with the game having been played on a flooded Sydney Cricket Ground surface.[60] The side continued touring the state before making their way north to Queensland, where they twice played the state side. The New Zealanders then returned to New South Wales where they faced Australia for the first time.[61]

Since the selection of the first New Zealand team in 1884, inter-colonial games had been played against New South Wales – for ten wins from thirteen matches, and Queensland – for seven wins, but none against a combined Australian side.[62] This changed on tour, and Gallaher was capped when New Zealand played their first ever Test match – against Australia in Sydney.[8] The match was won 22–3 by the New Zealanders, who scored three tries to nil. The last match of the tour was against New South Wales Country, which was won 32–0.[63] On their ten-match tour of Australia, New Zealand had scored 276 points, and conceded only 13.[58]

After returning from tour, Gallaher was selected for the North Island in his first ever Inter-Island match; won 12–5 by the South.[64] He then continued playing for Auckland, who were conducting a tour of both islands. Gallaher appeared in six of their seven matches:[55] against Taranaki, Wellington, Southland, Otago, Canterbury, and South Canterbury – the first two matches were lost, but the last four won.[64]

In 1904 the first Ranfurly Shield match was played; Gallaher played for Auckland in that game, but his side lost the shield in their 6–3 defeat to Wellington.[65] He was then selected for the New Zealand team that faced the touring British Isles side in what was New Zealand's first ever home Test match.[8] The British team were conducting a tour of Australia and New Zealand, and had finished their unbeaten Australian leg before travelling to New Zealand. The New Zealanders were coached by Jimmy Duncan, by then retired as a player, who said before the historic match: "I have given them directions. It's man for man all the time, and I have bet Gallaher a new hat that he can't catch [Percy] Bush. Bush has never been collared in Australia but he'll get it today".[66] The match was tied 3–3 at half-time, but New Zealand were the stronger side in the second half and eventually won 9–3.[67] While Gallaher was praised by press for his all-round display at wing-forward, it was in particular for his successful harassment of the British Isles' half-back Tommy Vile.[68]

That was the first tour loss for the British side, who then drew with a combined Taranaki-Wanganui-Manawatu side before travelling to Auckland. Gallaher played for Auckland against the tourists and scored one of the tries in their 13–0 victory.[69] He was part of a forward pack that dominated their opponents, and again he troubled Vile.[70] According to historian Terry McLean, "his display could be ranked with the finest exhibitions of wing-forward play" after his tackling of Vile and Bush killed many British attacks.[67] Gallaher represented Auckland once more that season, a 3–0 loss to Taranaki.[71]

1905 tour

Background and preparations

At the end of the 1904 season the New Zealand Rugby Football Union (NZRFU) suspended Gallaher from playing after a disagreement over a claim for expenses he had submitted to the Auckland Rugby Football Union for travel to play in the match against the British Isles.[72] Eventually the matter was resolved when, under protest, Gallaher repaid the disputed amount.[73] This settlement coupled with his performance in 26–0 North Island win over the South Island in the pre-tour trial allowed Gallaher to be considered for selection for New Zealand's 1905 tour of Europe and North America.[74]

Gallaher was named as the tour captain, with Billy Stead as vice captain.[75] A week into the voyage to Britain aboard the SS Rumutaka, rumours circulated that some of the southern players were not happy with what they perceived as an Auckland bias in the squad, and with the appointment of Gallaher.[76] Both Gallaher and Stead had been appointed by the NZRFU, but many of the players believed that the appointments should have been chosen by the team as per the practice on the 1897 and 1903 tours to Australia.[77] Gallaher recognised the damage factionalism could do to the team and offered to resign,[78] and so did vice-captain Stead.[77] Although the teams' manager refused to accept the resignations, the players still took a vote; 17 to 12 in favour of endorsing the NZRFU's selections.[79][80]

During the voyage to England the team conducted training drills; for this the forwards were coached by Gallaher and fellow player Bill Cunningham,[81] while in charge of the backs was vice-captain Stead.[82] Consequently the services of NZRFU-appointed coach Jimmy Duncan were not used; his appointment had caused opposition from many in the squad who believed his expertise was not required, and that an extra player should have been taken on tour instead.[83] After a six week voyage, on 8 September the team arrived in Plymouth, England.[84]

Early tour matches

No man before or since has been pilloried as was Gallaher in the British Isles in 1905, both by press and public. Castigated from all angles, Gallaher, in his firm belief that the wing-forward tactics were within the Laws, took it all with serenity.[85]

The first match was played against the Devon county side at Exeter, and while a close match was expected,[86] New Zealand ran out 55–4 winners; they scored twelve tries and conceded only a drop-goal. Reaction to the match was mixed – the team were accompanied by a cheering crowd and marching band following the win, but the play of Gallaher at wing-forward provoked some criticism in the press.[87] He was accused of obstruction, however referee Percy Coles – an official with England's Rugby Football Union (RFU) – rarely penalised him.[88] Billy Wallace blamed New Zealand's superior scrum for making Gallaher's play more prominent,[88][lower-alpha 4] while Gallaher later said "I think my play is fair – I sincerely trust so – and surely the fact that both Mr Percy Coles and Mr D. H. Bowen – two of the referees of our matches, and fairly representative of English and Welsh ideas, have taken no exception so it ought to have some weight."[90] The criticism of Gallaher and the wing-forward position by the British press continued throughout the tour.[8]

Following the opening match the All Blacks – as the New Zealand team came to be known[lower-alpha 5] – defeated Cornwall and then Bristol, both 41–0. They then defeated Northampton 32–0.[91] The tour continued in much the same way, with the All Blacks defeating Leicester, Middlesex, Durham, Hartlepool Clubs and Northumberland; in nearly all cases the defeats were inflicted without conceding any points, the one exception was Durham, who scored a try against the New Zealanders.[92] They then comfortably defeated Gloucester and Somerset before facing Devonport Albion – who were the English club champions.[93] The club had not lost at home in 18 months, but were beaten 21–3 in front of a crowd of 20,000. Gallaher scored the All Blacks' final try, which was described by the Plymouth Herald as, "... a gem. It was a tearing rush for about fifty yards with clockwork-like passing all the way".[94]

The team won their next seven matches, including victories over Blackheath, Oxford University and Cambridge University.[91] Full-back Billy Wallace believed the win over Blackheath was when their form peaked; he later said that "after this game injuries began to take their toll and prevented us ever putting in so fine a team again on the tour".[95] By the time the All Blacks played their first Test match, against Scotland, the team had played and won nineteen matches, and scored 612 points while conceding only 15.[96]

Scotland, Ireland and England internationals

The team were not warmly welcomed by administrators from the Scottish Football Union (SFU), the governing body for rugby union in Scotland; they did not receive an official welcome and were greeted by only one official on their arrival in Edinburgh.[97] As well, the SFU refused a guarantee for the match, but eventually promised the entire gate to the New Zealanders instead; this meant that the NZRFU had to take on all financial responsibilities for the match.[96][lower-alpha 6] One reason for the cold reception from the SFU may have been because of negative reports from David Bedell-Sivright, who was Scotland's captain and had also captained the British Isles team on their 1904 tour of New Zealand. Bedell-Sivright had reported unfavourably on his experiences in New Zealand the previous year, especially regarding the wing-forward play of Gallaher.[98]

When time for the Scotland Test did arrive, it was discovered that as the ground had not been covered for protection from the elements, and was consequently frozen from frost.[99] The SFU wanted to abandon the match, but Gallaher and tour manager George Dixon believed the weather would improve enough to thaw the frost,[100] and the match was allowed to proceed.[97][101] The Test was closely contested, with Scotland leading 7–6 at half-time, however the All Blacks scored two late tries to win 12–7; despite the close score-line, the New Zealanders were clearly the better of the two sides.[102][103]

Four days later they played a West of Scotland selection, where they received a much warmer reception than for the Scotland match, before travelling via Belfast to Dublin where they faced Ireland in a Test match. Gallaher did not play in either match due to a leg injury suffered during the Scotland Test.[104] The Ireland match was comfortably won 15–0, and was followed up by defeat of Munster.[91] The next game was against England in London – by this point Gallaher had recovered from his injury.[105][106]

The England game was played in front of between 40,000 and 80,000 spectators,[107][lower-alpha 7] and the All Blacks won convincingly, scoring five tries (four to wing Duncan McGregor) to win 15–0.[97] According to England player Dai Gent, the victory would have been greater if the match conditions had been dry.[108] Following the England match Gallaher said: "One cannot help thinking that England might have picked a stronger side. From our experience, we did not think that this side was fully representative of the best men to be found in the country".[109] Gallaher's form during the match showed that he was still suffering from his leg injury.[110] Three more matches were contested in England, wins over Cheltenham, Cheshire, and Yorkshire, before the team travelled to Wales.[111][57]

Wales

Three days after defeating Yorkshire, Gallaher and his team faced Wales.[112] By this point the All Blacks had played 27 matches on tour, scoring 801 points while conceding only 22,[102] and all in only 88 days.[113] They were struggling to field fifteen fit players, and a number of their best players, including Stead, were unavailable.[114][115] Wales were the dominant rugby country of the four Home Nations, and were in the middle of a "golden age".[116][lower-alpha 8]

The match was preceded by an All Black haka, and the crowd responded by singing Land of my Fathers – the Welsh national anthem.[97] The match was closely contested, but Wales were the better side. They had developed tactics to negate the New Zealander's seven-man scrum,[117] and removed a man from their scrum to play as a 'rover' – equivalent to Gallaher's wing-forward position.[118] As well as this Gallaher was consistently penalised by the Scottish referee, John Dallas,[118] for allegedly feeding the ball into the scrum incorrectly.[119] This eventually forced Gallaher to instruct his team not to contest for possession at the scrums.[119] Bob Deans later said that Dallas had gone "out to penalise Gallaher – there is no doubt about that".[120] The Welsh eventually scored an unconverted try, to Teddy Morgan, shortly before half-time to lead 3–0.[121]

The All Black backs had been poor in the first half,[118] and the general form of the side well below that they had displayed earlier in the tour.[117] However the team were the better side in the second half,[118][122] with the play of Welsh fullback Bert Winfield keeping Wales in the game.[118] The most controversial of the tour happened late the half when Wallace recovered a Welsh kick and cut across the field,[97] and with only Winfield to beat, passed to wing Deans.[123][124] What happened next has provoked intense debate, but one of the Welsh players tackled Deans, and he either fell short of the try-line, or placed the ball over it before being dragged back.[125][97] Referee Dallas, who was unsuitably dressed for the role, was behind the play, and when he arrived deemed that Deans was short of the try-line.[125][126] Play continued, but the All Blacks could not score, and Wales won 3–0; New Zealand's first loss of the tour.[97]

Following the match Gallaher was asked if he was unhappy with any aspect of the game, and replied that "the better team won and I am content".[127] When asked about the refereeing of Dallas, he said "I have always made it a point never to express a view regarding the referee in any match in which I have played".[128] Gallaher was gracious in defeat, but Dixon was highly critical of Dallas, and the Welsh newspapers, who he said had "violently and unjustly" attacked the captain.[129] Later Gallaher would admit that he was annoyed at the criticism he was subjected to in Wales, which he found unfair – he also pointed out that the Welsh had adopted some elements of wing-forward play, despite their condemnation of the position.[130][131][26] Later on the tour, when discussing the issue of his feeding the ball into the scrum, he said:[26]

No referee could accuse me throughout the tour of putting the ball in unfairly or of putting ‘bias’ on it. I would be quite content to accept the verdict on such referees as Mr. Gil Evans or Mr. Percy Coles on the point. There were times when the scrum work was done so neatly that as soon as the ball had left my hands the forwards shoved over the top of it, and it was heeled out, and Roberts was off with it before you could say ‘knife’. It was all over so quickly that almost everyone – the referee sometimes included – thought there was something unfair about it, some ‘trickery’ and that the ball had not only been put in but passed out unfairly. People here have been accustomed when the ball was put into the scrum to see it wobbling about and frequently never coming out in a proper way. How can a man possibly put ‘bias’ on a ball if he rolls it into the scrum? The only way to put my screw on a ball would be, I would say, to throw it straight down, shoulder high, on to its end, so that it may possibly bounce in the desired direction. I have never done that – in fact, it can’t be done in the scrum and if I had ever attempted it I should have expected to be penalised immediately.— Dave Gallaher

Four more matches were contested in Wales,[97] with Gallaher appearing in three.[57] He played against Glamorgan, won 9–0, but had his finger bitten, which was serious enough for him to miss the fixture against Newport. He returned to face Cardiff – who were Welsh champions – on Boxing Day.[132] Gallaher was again booed by the Welsh crowd, and again the All Blacks were troubled in the scrum, this time after losing a player to injury.[lower-alpha 9] The New Zealanders won narrowly, and Gallaher admitted after the match that Cardiff was the strongest club side they had met.[133] The team then faced Swansea in their last match in the British Isles;[91] Gallaher against struggled to field a fit side, and at 3–0 down late in the match they were heading for their second defeat on tour. However Wallace kicked a drop-goal – then worth four points – late in the game to give the All Blacks a 4–3 victory.[134]

France, North America, and return

The side departed Wales and travelled to Paris, where they faced France on 1 January. This was France's first ever Test match, which the All Blacks won 38–8. The match was comfortably won by the New Zealanders, who eased off in the second half after leading 18–3 at the break.[135] After the French scored their second try, giving them 8 points – the most any team had scored against the All Blacks – the New Zealanders responded with six unanswered tries.[136] After returning to London the team discovered that New Zealand's Prime Minister – Richard Seddon – had arranged for them to return home via North America. Not all of the players were keen on the idea, and four did not make the trip,[lower-alpha 10] but the team had over two weeks to spend in England before their departure.[97]

The side travelled to New York, playing an exhibition game, before making their way to San Francisco. There they played two official matches, against British Columbia, with both won easily. These were the last matches of the tour; 35 games had been played for only one loss, and Gallaher had played in 26 of those matches, including four Tests.[137][57] Over their 32 matches in the British Isles the side scored 830 points and conceded 39, and overall they scored 976 points and conceded only 59.[97] The team finally arrived in New Zealand at Auckland on 6 March 1906 where they were welcomed by a crowd of 10,000 before being hosted at a civic reception.[138] Gallaher was invited to speak at the reception, saying: "We did not go behind our back to talk about the Welshman, but candidly said that on that day the better team had won. I have one recommendation to make to the New Zealand [Rugby] Union, if it was to undertake such a tour again, and that is to play the Welsh matches first".[139]

The Complete Rugby Footballer

Before the squad departed Britain for North America, Stead and Gallaher were approached by English publisher Henry Leach to author a book on rugby tactics and play.[140] They were each paid £50 and completed the book in less than two weeks. The book, The Complete Rugby Footballer, was 322 pages and included chapters on tactics and play, as well as a summary of rugby's history in New Zealand including the 1905 tour.[141] It was mainly authored by Stead, a bootmaker, with Gallaher contributing most of the diagrams.[142] Gallaher almost certainly made some contributions to the text, including sections on Auckland club rugby, and on forward play.[143] The book "remains one of the most influential books produced in the realms of rugby literature",[144] and according to Matt Elliott is "marvellously astute".[145] It showed that the All Blacks' tactics and planning were superior to others of the time,[57] and reaction to its publication was universally positive.[146]

Aftermath and impact

The 1905 Originals are remembered as perhaps the greatest of All Black sides,[3] and set the standard for all their successors.[147] They introduced a number of innovations, including specialised forward positions.[97] But while their success helped establish rugby as New Zealand's national sport and fed a growing sporting nationalism,[148][149] the controversial wing-forward position contributed to strained ties with the Home Nations' rugby authorities.[150] British and Irish administrators were also weary of New Zealand's commitment to the amateur ethos, and questioned their sportsmanship.[150] Many in the traditional rugby establishment believed that: "Excessive striving for victory introduced an unhealthy spirit of competition, transforming a character-building 'mock fight' into 'serious fighting'. Training and specialization degraded sport to the level of work".[151]

The success of the Originals provoked plans for a professional team of players to tour England and play Northern Union clubs in what is now known as rugby league. Unlike rugby league, which was professional, rugby union was strictly amateur at the time,[lower-alpha 11] and in 1907 a professional team from New Zealand, known as the All Golds (originally a play on All Blacks) toured England and Wales before introducing rugby league to both New Zealand and Australia.[153][lower-alpha 12] According to historian Greg Ryan, the All Golds tour "confirmed many British suspicions about the rugby culture that had shaped the 1905 team".[150]

These factors may have contributed to the gap between All Black tours of the British Isles – they next toured in 1924.[155][lower-alpha 13] As well as that, the NZRFU was denied representation on the International Rugby Football Board (IRFB) – which composed of members exclusively from England, Ireland, Scotland and Wales – until 1948.[156] After complaining of the wing-forward for years, the Home Nations-dominated IRFB made a series of law changes effectively outlawing the position in 1931.[157]

Auckland and All Black selector

He retired from playing after the All Blacks' tour,[130] but remained involved in the sport as a coach and selector.[26] He coached at age group level for Ponsonby, and in 1906 succeeded Fred Murray as sole selector of the Auckland provincial team.[26][158] He was Auckland selector until 1916; over this time Auckland played 65 games, won 48, lost 11 and drew 6.[2] Gallaher did make a brief comeback as a player – travelling as the selector of an injury depleted Auckland team – he turned out against Marlborough at Blenheim in 1909; Marlborough won 8–3.[159] He also played against the Maniapoto sub-union just over a week later.[160] Between 1905 and 1913 Auckland held the Ranfurly Shield; defending it 23 times. The team struggled to retain the shield during 1912 and 1913, and eventually lost it to Taranaki after a 14–11 defeat.[1] Notable victories for Auckland while Gallaher was selector include a 11–0 defeat of the touring 1908 Anglo-Welsh side,[161] against the New Zealand Māori in 1910,[162] and a 15–11 defeat of Australia in 1913.[163]

He was a national selector from 1907 to 1914,[lower-alpha 14] and co-coached the All Blacks against the 1908 Anglo-Welsh team alongside George Nicholson. A number of Gallaher's team-mates from the 1905–06 tour were included in the New Zealand squad during the series, and the All Blacks eventually won two, and drew one, of the three Tests.[131] During his period as national selector, the All Blacks played 50 games (including 16 Tests), won 44, lost 4 and drew 2. They won 13 Tests, drawing two and losing one.[2] While selector he still found time to coach the Auckland Grammar School rugby team.[165]

First World War

Although exempt from conscription due to his age,[57] Gallaher enlisted in May 1916. While awaiting for his call-up to begin training he learnt that his younger brother Company Sergeant-Major Douglas Wallace Gallaher had been killed while serving with the 11th Australian Battalion at Laventie near Fromelles on 3 June 1916.[166] Prior to the war Douglas had been living in Perth, Australia and had previously been wounded at Gallipoli.[167] Biographer Matt Elliott describes it as a "myth" that Gallaher enlisted to avenge his younger brother;[168] rather he claims that it was most likely due to "loyalty and duty".[169]

After enlisting and completing his basic training at Trentham he was posted to 22nd Reinforcements, 2nd Battalion of the Auckland Regiment, New Zealand Division.[164][170] On 16 February 1917 he sailed from New Zealand aboard the Aparima.[171] The force reached Devonport, Plymouth on 2 June,[171] where he was promoted to the rank of temporary sergeant and was dispatched to Sling Camp for further training. On 1 June 1917 his rank was confirmed as sergeant.[170]

Gallaher's unit fought in the Third Battle for Ypres, near La Basse Ville, and in August and September they trained for the upcoming Passchendaele offensive.[164] In the attack on Gravenstafel Spur on 4 October 1917, Gallaher was wounded by a piece of shrapnel that penetrated through his helmet and died later that day at the 3rd Australian Casualty Clearing Station, Gravenstafel Spur, aged almost 44.[172][173]

He is buried in grave No. 32513 at Nine Elms British Cemetery,[174] which is located west of Poperinge on the Helleketelweg, a road leading from the R33 Poperinge ring road in Belgium. His regulation gravestone bears the silver fern – and incorrectly gives his age as 41. Since 1924, All Blacks teams playing in Britain and France have made pilgrimages to this grave site.[175] For his war service he was posthumously awarded the British War Medal, and Victory Medal.[51] His brother Henry who was a miner served with the Australian 51st Battalion and was killed on 24 April 1917.[176] Henry's twin brother, Charles, also served in the war and survived being badly wounded at Gallipoli.[167]

Leadership and personality

That Gallaher was a talented leader is considered beyond dispute.[57] His military experience gave him an appreciation for "discipline, cohesion and steadiness under pressure".[8] He was however quiet,[8] even dour,[26] and preferred to lead by example.[177] He insisted players spend an hour "contemplating the game ahead" on match days, and also that they pay attention to detail.[147] Original All Black Ernie Booth wrote of Gallaher: "To us All Blacks his words would often be, ‘Give nothing away; take no chance.’ As a skipper he was somewhat a disciplinarian, doubtless imbibed from his previous military experience in South Africa. Still, he treated us all like men, not kids, who were out to ‘play the game’ for good old New Zealand”.[26] Another contemporary said he was "perhaps not the greatest of wing-forwards, as such; but he was acutely skilled as a judge of men and moves".[178] According to historian Terry McLean: "In a long experience of reading and hearing about the man, one has never encountered, from the New Zealand angle, or from his fellow players, criticism of his qualities as a leader".[178]

Personal life

On 10 October 1906 Gallaher married "Nellie" Ellen Ivy May Francis at All Saints Anglican Church, Ponsonby, Auckland.[179][164] Nellie was the daughter of Nora Francis, and the sister of New Zealand dual-code rugby international Arthur ('Bolla') Francis.[180] For many years prior to the marriage Gallaher had boarded at the Francis family home,[164] where he had come to know Nellie who was eleven years younger than him.[179] Both had also attended the All Saints Anglican Church where Nellie sang in the choir. With his limited income and frequent absences from work playing rugby he found boarding his best accommodation option.[180] On 28 September 1908 their daughter Nora Tahatu (later Nora Simpson) was born.[181] Nellie Gallaher died in January 1969.[174]

Gallaher's brother-in-law Bolla Francis played for Ponsonby, Auckland and New Zealand sides for a number of years, including when Gallaher was a selector. In 1911, at age 29, and in the twilight of his All Blacks' career, he decided to switch to the professional sport of rugby league. It is unlikely this was done without Gallaher's knowledge.[182] Francis did eventually return to rugby union as a coach.[130]

Gallaher was also a member of the fraternal organisation the United Ancient Order of the Druids, and attended meetings fortnightly in Newton, not far from Ponsonby.[183] He also played several sports in addition to rugby, including cricket, yachting and athletics.[184]

Memorials

In 1922, the Auckland Rugby Football Union introduced the Gallaher Shield in his honour as the trophy for that union's premier men's club competition. Gallaher's club Ponsonby have won the title more than any other club.[185] The Dave Gallaher Trophy is contested between New Zealand and France.[186] The trophy is held by the side that wins a one-off Test or Test series, and was first awarded when New Zealand defeated France on Armistice Day in 2000.[187] Gallaher has been inducted into the International Rugby Hall of Fame,[35] the IRB Hall of Fame,[26] and the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame.[188][lower-alpha 15]

In 2005 members of the All Blacks witnessed the unveiling of a plaque at Gallaher's birthplace in Ramelton,[187] which was presented in conjunction with the renaming of Letterkenny RFC's home ground to Dave Gallaher Park.[57] Gallaher's name is also incorporated into the club's crest.[187] The ground was upgraded following its renaming, and in 2012 the Letterkenny section of the ground was opened by former All Black, and Ponsonby stalwart, Bryan Williams.[190][191]

In 2011 New Zealand's then oldest living All Black, Sir Fred Allen, unveiled a 2.7-metre (8 ft 10 in) high bronze statue of Gallaher besides one of the entrances at Eden Park in Auckland. The statue was created by Malcolm Evans.[192]

See also

Footnotes

Notes

- ↑ Isabella, James and Jane all died as infants.[4]

- ↑ James Patrick was left with family in Ireland, but died aged two.[7]

- ↑ For a description of the archaic wing-forward position and 2-3-2 scrum formation used by teams throughout New Zealand at the time see Thomas Ellison § Wing-forward.

- ↑ Unlike teams in the British Isles, the New Zealanders employed specialists positions for their players within the scrum. This meant that despite often facing an extra man, the New Zealand scrum "drove like a cleaver through British forward packs".[89]

- ↑ For background on how the name was popularised on the tour see The Original All Blacks § Name.

- ↑ In addition, the SFU initially refused to award caps for the match, and even demanded that the New Zealanders supply the ball.[97]

- ↑ The discrepancy in crowd size is because the unknown number of non-paying spectators.[107]

- ↑ Wales had won the Triple Crown in 1905.[114]

- ↑ There was no provision for injury replacements.

- ↑ All returned to New Zealand however.[97]

- ↑ The International Rugby Board slowly loosened the amateur regulations, especially for international players, before declaring the game "open" to professionals in late 1995.[152]

- ↑ The All Golds also appropriated the playing colours and name of the All Blacks for their tour.[154]

- ↑ Between visits a South African team was twice invited to tour.[155]

- ↑ Unlike with Auckland where he was sole selector, New Zealand had three other selectors alongside Gallaher.[164]

- ↑ The collective 1905 All Blacks are also an inductee into the New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame.[189]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Verdon 2000, p. 30.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Elliott 2012, p. 283.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 McLean 1987, p. 34.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Elliott 2012, p. 13.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 McLean 1987, p. 35.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Elliott 2012, p. 32.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 8.7 McLean 2013.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Elliott 2012, p. 18.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 24.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 27.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 28–29.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 30.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 29.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 28.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 17–18.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 31.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 33–34.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 34–36.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 36–37.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 37.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 48.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 49.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Elliott 2012, p. 62.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Elliott 2012, p. 50.

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 26.3 26.4 26.5 26.6 26.7 "2010 Inductee".

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 52.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Elliott 2012, pp. 56–57.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 57.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 59.

- ↑ "in New South Wales and Queensland".

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 60.

- ↑ Swan & Jackson 1952.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 61.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Dave Gallaher (IRHF).

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 36.3 McLean 1987, p. 36.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 79.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 80.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 271.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 81.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 69.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 91.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 93–95.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 94.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 95.

- ↑ 49.0 49.1 Elliott 2012, p. 97.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 98.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 51.2 51.3 51.4 McLean 1987, p. 37.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 99.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 103.

- ↑ McCarthy 1968, p. 27.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 McLean 1987, p. 38.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 104.

- ↑ 57.0 57.1 57.2 57.3 57.4 57.5 57.6 57.7 Dave Gallaher (NZRU).

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Verdon 2000, p. 19.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 107.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 107–108.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Verdon 2000, p. 17.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 110.

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 Elliott 2012, p. 111.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 114–115.

- ↑ Verdon 2000, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ 67.0 67.1 McLean 1987, p. 40.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 122–124.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 124–125.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 126.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 126–128.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 130–31.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 131–32.

- ↑ Ryan 2005, p. 196.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 145–146.

- ↑ 77.0 77.1 Ryan 2005, p. 63.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 146.

- ↑ Ryan 2005, p. 64.

- ↑ McLean 1987, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 149.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 26.

- ↑ Verdon 2000, p. 20.

- ↑ Tobin 2005, p. 30.

- ↑ McCarthy 1968, p. 41.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 154.

- ↑ 56th All Black Game.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 Elliott 2012, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 45.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 159–160.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 91.2 91.3 "in the British Isles, France and North America".

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 160–161.

- ↑ Tobin 2005, p. 59.

- ↑ 67th All Black Game.

- ↑ Tobin 2005, pp. 72–73.

- ↑ 96.0 96.1 McCarthy 1968, p. 45.

- ↑ 97.0 97.1 97.2 97.3 97.4 97.5 97.6 97.7 97.8 97.9 97.10 97.11 97.12 1905/06 'Originals'.

- ↑ McLean 1987, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 41.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 166–167.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 42.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 McCarthy 1968, p. 46.

- ↑ 4th All Black Test.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 169.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 171–172.

- ↑ 6th All Black Test.

- ↑ 107.0 107.1 Elliott 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Gabe 1954, p. 38.

- ↑ Gabe 1954, p. 37.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 174.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 176.

- ↑ Gabe 1954, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 177.

- ↑ 114.0 114.1 Elliott 2012, p. 178.

- ↑ McCarthy 1968, p. 47.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 46.

- ↑ 117.0 117.1 Gabe 1954, p. 42.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 118.2 118.3 118.4 McCarthy 1968, p. 48.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 Elliott 2012, p. 180.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 202.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 181.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 182.

- ↑ McCarthy 1968, pp. 48–49.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 182–183.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 Elliott 2012, pp. 183–184.

- ↑ McCarthy 1968, p. 49.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 184–185.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 185.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 185–186.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 McLean 1987, p. 47.

- ↑ 131.0 131.1 Verdon 2000, p. 29.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 188.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 189.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 189–190.

- ↑ 8th All Black Test.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 193.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 197–198.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 198–199.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 200–201.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 205.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 207–208.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 206.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 208.

- ↑ Jenkins 2011.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 210.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 211–213.

- ↑ 147.0 147.1 Verdon 2000, p. 27.

- ↑ Ryan 2011, pp. 1409–1410.

- ↑ King 2003, p. 281.

- ↑ 150.0 150.1 150.2 Ryan 2011, p. 1411.

- ↑ Vincent 1998, p. 124.

- ↑ Williams 2002, pp. 128–133.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 221–224.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 224.

- ↑ 155.0 155.1 Ryan 2011, pp. 1412–1414.

- ↑ Ryan 2011, p. 1422.

- ↑ Ryan 2011, p. 1421.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 218.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 242.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 244.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 236.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 246.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 252.

- ↑ 164.0 164.1 164.2 164.3 164.4 McLean 1987, p. 48.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 241.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 258–259.

- ↑ 167.0 167.1 Elliott 2012, pp. 257–258.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 258.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 259.

- ↑ 170.0 170.1 Elliott 2012, p. 267.

- ↑ 171.0 171.1 Elliott 2012, p. 264.

- ↑ McLean 1987, p. 49.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 272–274.

- ↑ 174.0 174.1 Elliott 2012, p. 278.

- ↑ New Zealand Army Museum http://www.armymuseum.co.nz/kiwis-at-war/voices-from-the-past/sergeant-dave-gallaher-32513/. Retrieved 22 April 2015. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 276.

- ↑ Gallagher 2000.

- ↑ 178.0 178.1 McLean 1987, p. 44.

- ↑ 179.0 179.1 Elliott 2012, p. 219.

- ↑ 180.0 180.1 Elliott 2012, p. 112.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 239.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 247.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 221.

- ↑ Elliott 2012, p. 279.

- ↑ "Gallaher statue ..".

- ↑ 187.0 187.1 187.2 Elliott 2012, p. 280.

- ↑ Dave Gallaher (NZ Sports Hall of Fame.

- ↑ All Blacks, 1905.

- ↑ "All Blacks legend to unveil ..".

- ↑ Walsh 2012.

- ↑ Horrell 2011.

Sources

Books and articles

- Carter, A. Kay (2011). Maria Gallaher – Her Short Life and Her Children's Stories. Paraparaumu. ISBN 9780987653802.

- Elliott, Matt (2012). Dave Gallaher – The Original All Black Captain (paperback). London: Harper Collins. ISBN 978-1-86950-968-2.

- Gabe, Rhys T. (1954). "The 1905–06 Tour". In Wooller, Wilfred; Owen, David. Fifty Years of the All Blacks: A Complete History of New Zealand Rugby Touring Teams in the British Isles. London: Phoenix House Ltd.

- King, Michael (2003). The Penguin History of New Zealand. New Zealand: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-301867-4.

- McCarthy, Winston (1968). Haka! The All Blacks Story. London: Pelham Books.

- McLean, Terry (1987). New Zealand Rugby Legends. Auckland, New Zealand: MOA Publications. ISBN 0-908570-15-5.

- Ryan, Greg (2005). The Contest for Rugby Supremacy – Accounting for the 1905 All Blacks. Canterbury University Press. ISBN 1-877257-36-2.

- Ryan, Greg (2011). "A Tale of Two Dinners: New Zealand Rugby and the Embrace of Empire, 1919–32". The International Journal of the History of Sport (Routledge) 28 (10): 1409–1425. doi:10.1080/09523367.2011.577641.

- Swan, Arthur C.; Jackson, Gordon F. W. (1952). Wellington's Rugby History 1870 – 1950. Wellington, New Zealand: A. H. & A. W. Reed.

- Tobin, Christopher (2005). The Original All Blacks 1905–06. Auckland, New Zealand: Hodder Moa Beckett. ISBN 1-86958-995-5.

- Verdon, Paul (2000). Born to Lead – The Untold Story of the All Black Test Captains. Auckland, New Zealand: Celebrity Books. ISBN 1-877252-05-0.

- Vincent, V. T. (1998). "Practical Imperialism: The Anglo‐Welsh Rugby Tour of New Zealand, 1908". The International Journal of the History of Sport (Routledge) 15 (1): 123–140. doi:10.1080/09523369808714015.

- Williams, Peter (2002). "Battle Lines on Three Fronts: The RFU and the Lost War Against Professionalism". The International Journal of the History of Sport (Routledge) 19 (4): 114–136. doi:10.1080/714001793.

News

- "All Blacks legend to unveil plaque at Dave Gallagher Park in Letterkenny". Donegal Democrat. 1 November 2012. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- "Gallaher statue unveiled at Eden Park". sportal.co.nz. 15 July 2011. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Gallagher, Brendan (3 November 2000). "Hero Gallaher remembered". The Telegraph. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Horrell, Rhiannon (15 July 2011). "Eden Park unveils statue of legend". stuff.co.nz. Retrieved 5 September 2014.

- Jenkins, Graham (25 September 2011). "Rucking all over the world". ESPN. Retrieved 8 October 2014.

- Walsh, Harry (3 November 2012). "All Black legend visits Letterkenny". Derry People Donegal News. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

Web

- "4th All Black Test". allblacks.com. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "6th All Black Test". allblacks.com. Retrieved 4 November 2014.

- "8th All Black Test". allblacks.com. Retrieved 10 November 2014.

- "56th All Black Game". allblacks.com. Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- "67th All Black Game". allblacks.com. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- "2010 Inductee: Dave Gallaher". International Rugby Board. 15 May 2011. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- "Dave Gallaher". The International Rugby Hall of Fame. Archived from the original on 12 May 2013.

- "Dave Gallaher". allblacks.com. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "in New South Wales and Queensland". allblacks.com. Retrieved 23 October 2014.

- "in the British Isles, France and North America". allblacks.com. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- McLean, Denis (25 September 2013). "Gallaher, David". Dictionary of New Zealand Biography. Te Ara – the Encyclopedia of New Zealand. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "The 1905/06 'Originals'". New Zealand Rugby Museum. Archived from the original on 26 March 2013. Retrieved 26 March 2013.

- "Dave Gallaher". New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- "All Blacks, 1905". New Zealand Sports Hall of Fame. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dave Gallaher. |

- "Casualty Details – Gallaher, David". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "Passchendaele Casualty Forms – Gallaher, David". Archives New Zealand. Retrieved 6 August 2014.

- "David Gallaher's Death". Evening Post (Wellington). 16 January 1918. p. 8. Retrieved 17 March 2013.

- Baines, Huw. "Dave Gallaher". ESPN. Retrieved 8 August 2014.

- "New Zealand Footballers: The All Blacks' Arrival & Reception at Auckland, 1906". The New Zealand Archive of Film, Television and Sound Ngā Taonga Whitiāhua Me Ngā Taonga Kōrero. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

|