Das Mirakel (1912 film)

| Das Mirakel | |

|---|---|

|

Publicity shot for Mirakel | |

| Directed by | Mime Misu |

| Screenplay by | Mime Misu |

| Based on | The Miracle (play) by Karl Vollmoeller |

| Starring | Lore Giesen, Mime Misu, Anton Ernst Rückert |

| Cinematography | Emil Schünemann |

Production company | |

| Distributed by |

New York Film Company (USA) Elite Sales Agency (UK) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 4,000 feet |

| Country | Germany |

| Language | Silent with intertitles |

Das Mirakel is a black-and white silent German film made and released in 1912, directed by Mime Misu for the Berlin film production company Continental-Kunstfilm GmbH. It was based (without permission) on the Karl Vollmoeller play The Miracle. The film was originally advertised as The Miracle in Britain and the USA, but after copyright litigation in both countries it was shown as Sister Beatrix and Sister Beatrice respectively. In Germany it was known as Das Marienwunder: eine alte Legende.[1]

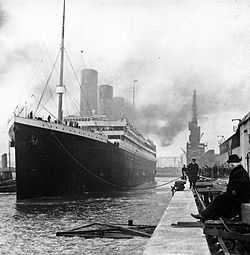

The film stars Lore Giesen, Mime Misu and Anton Ernst Rückert. The screenplay was by Mime Misu, and the cinematographer was Emil Schünemann, who was also behind the camera for Misu's film about the RMS Titanic disaster, In Nacht und Eis (Shipwrecked in Icebergs').

Plot

The film opens in the nave of a cathedral. People cry out in awe as a blind woman's lost sight is restored. A procession forms, including many pilgrims and nuns. They pass through the cloisters, chanting.

Among the nuns there is one younger and more beautiful named Beatrix. Among the pilgrims is a handsome knight. The two are attracted to each other during the service in the cathedral. Disturbed by her weakness Beatrix struggles to control her emotions.

Gradually the knight overcomes the Beatrix's resistance, aided by the Spirit of Evil, a sinister apparition that makes its appearance several times throughout the story. It in turn is countered by a second apparition that appears as a beautiful nun, the Spirit of Good.

When worshippers leave the cathedral after vespers, Beatrix throws down her robe and keys and flees with her handsome knight. The building is now empty and silent, with light falling on the motionless statue of the Virgin. Then the miracle happens. The statue of the Madonna comes to life and steps down from her throne. She picks up the garment discarded by the infatuated nun, and takes up her place before the barren altar.

The other nuns return notice that the statue of the Virgin has vanished. Assuming it has been stolen, they turn upon the woman they think to be Beatrix, and are about to lead her with execrations when the Madonna rises slowly from her feet into the air, and stands before them.

In the second half of the drama deals with the adventures of the nun in the world. We see her gradual degradation physically and spiritually as she goes from one lover to another. The Spirit of Evil urges on her degradation and uses her as a pawn to destroy the souls of others she encounters.

At last, the Spirit of Good appears and leads a worn out Beatrix back to the gates of the cathedral. She sneaks inside afraid and ashamed. She finds the cathedral empty except for a single figure, which stands motionless before the empty altar. Beatrix goes forward to throw herself upon the mercy of the solitary watcher—and then the figure turns, and the Madonna reveals herself to the nun whose place she has taken.

Beatrix is about to run in fright when the sanctuary gates close miraculously, and she finds herself imprisoned in the cathedral. She prostrates herself upon the ground. A smile of pity comes over the face of the Virgin Mother. She stretches out her hand and raises Beatrix up. She then returns to her throne, leaving the pardoned penitent Beatrix to take up the pure life once again. Beatrix is now tranquil. A shaft of sunlight breaks through the cathedral windows and illuminates the scene.[2]

Background

Two films with the title The Miracle were made and released in 1912: the Continental-Kunstfilm version directed by Mime Misu, and the 'authorised' version (possibly directed by Michel Carré) with most of the principal cast, the costumes and music from the original London production by Max Reinhardt of The Miracle (play).

- Das Mirakel (1912 film) produced by Continental-Kunstfilm GmbH (UK & US working title: The Miracle)

- The Miracle (1912 film) by Joseph Menchen (German title: Das Mirakel)

From December 1911 to March 1912 London's Olympia Exhibition Hall exhibition hall was turned into an enormous stage set for one of the biggest theatrical shows London had ever experienced. This was Max Reinhardt's production of The Miracle (play), a wordless mime play (US:Pantomime) by Karl Vollmoeller with music by Engelbert Humperdinck. The production involved (apart from the 15 or so principal players) a cast of around 1,000 minor players plus girl dancers and miscellaneous boys and girls, with an orchestra of 200 players, a chorus of 500 and a specially-installed organ.[3] This spectacular mediaeval pageant was performed before a nightly audience of 8,000, with two matinees a week.

Although Vollmoeller's play had been copyrighted, it was largely based on the well-known legend of 'Sister Beatrice', originally collected in the 13th century by Caesar of Heisterbach in his Dialogus miraculorum (1219-1223).[4] The tale was revived by Maurice Maeterlinck in 1901 in a minor play named Soeur Beatrice (Sister Beatrice), drawing on versions by Villiers de l'Isle-Adam and on the 14th-century Dutch poem Beatrijs.

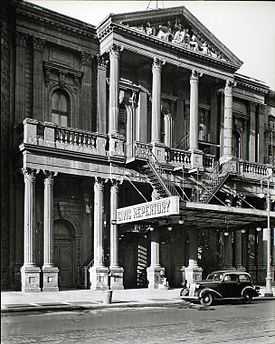

The legitimate worldwide film rights to the Reinhardt production, and to the play and the music, were acquired by Joseph Menchen, an inventor who had built up his own electrical theatre lighting business in New York.[5] He had been previously involved in the earliest days of the cinema, projecting early Edison and Vitascope films with his Kineoptikon at Tony Pastor's vaudeville theatre in New York from 1896-1899.[6]

From the outset the advertising for the Continental version played heavily on the play's success at Olympia, hinting (without explicitly claiming) that it was a film of the actual production.

Continental's film was completed and copyrighted by October 1912, while Joseph Menchen's authorised production of The Miracle (1912 film) started production near Vienna, Austria in early October and was finished by December 1912.

Production

Some of the film was shot on location at Chorin Abbey (Kloster Chorin) near the German-Polish border.[7]

According to evidence given in a copyright court case involving the two 'Miracle' films, production of Das Mirakel began in Germany in March 1912, and was finished by July 1912.[5] However, from after April until July Misu was engaged in filming In Nacht und Eis, which was passed by the Berlin censors on 6 July.[8] It seems possible, therefore, that Das Mirakel was already in production when the Titanic sank, and that Misu immediately made In Nacht und Eis before completing Mirakel. At any rate, the Berlin police censor's decision to ban the film (possibly for its pro-catholic stance) was dated 19 October 1912.[8][9]

Timeline

"Battle of the Miracles"

Although Das Mirakel (under the title "The Miracle") was well-received by the critics in the USA, it seems to have been made in a deliberate attempt to compete with the 'authorised' film of Max Reinhardt's production, The Miracle (1912 film) produced and co-directed by Joseph Menchen and Michel Carré. The release of two visually similar films in 1912 (one authorized, one not) with the same title and dealing with the same subject has inevitably led to confusion, including the false notion that a film named "The Miracle" went down with the RMS Titanic. See The Miracle (1912 film)#US performances.

The film's history is inextricably intertwined with that of Menchen's.

- The Miracle US: Sinking of the Titanic, death of Henry Harris (Menchen's US distributor), April 1912. Al. Woods buys US rights after this date & before May announcement on return to US. Woods acquired the rights in April, according to (Frohlich & Schwab 1918, pp. 412–415)

- The Miracle US: Woods prints a warning that he owns the motion picture rights in the US [10]

- Das Mirakel US: A trade magazine ad reads "Coming Soon!! The Miracle. A sensational Cathedral play that aroused discussion throughout the world. New York Film Co, 12 Union Square, New York.2"[11]

- The Miracle UK: In June 1912 Menchen announced in the British cinema trade press that a colour film (with voice effects) of The Miracle was going to be made in Vienna, the next venue for Reinhardt's production.[12]

- Das Mirakel US: Continental-Kunstfilm appointed the New York Film Company as their US distributors as from 1 July 1912, and announced the future release of four films including In Nacht und Eis (At Night Through Icebergs) and The Miracle (Das Mirakel)[13]

- Das Mirakel UK: Elite Sales Agency formed on 3 October 1912.[14]

- The Miracle AT: Shooting started Monday 7 October 1912 in Perchtoldsdorf, Vienna.[15]

- Das Mirakel US: Imported the film (as negatives?)[16][17] into US 9 October. Al Woods attempted to have the film confiscated by the US Customs on the grounds that he owned the rights to the film. The chief customs officer declined to intervene, and decided it was a matter for a judge.[18] The matter eventually came to court on 3 March 1913.[19]

- Das Mirakel US: Das Mirakel first shown in the US to Al Woods' lawyers and the press at 9 a.m. on Friday 18 October 1912 at the Fourteenth Street Theatre, New York[20][21]

- Das Mirakel DE: Misu's film banned by the Berlin police censor on 19 October 1912[22]

- Das Mirakel US: Film copyrighted in the USA as The Miracle: a legend of mediaeval times on 24 October 1912.[23]

- Das Mirakel UK: Trade press ad, 5 November 1912 : "The Elite Sales Agency of Gloucester Mansions, Cambridge Circus, have secured a remarkably fine film of The Miracle, which runs to a length of some 4,000 feet [...] The drawing power of The Miracle when it was at Olympia was unlimited and, as with the play, so it will be with the film ; for The Miracle is a spectacle of which one can never tire."[24]

- Das Mirakel US: New York Film Co. took out a full-page advertisement "10 Facts about the Miracle, and one Don't", 16 November 1912 [20]

- The Miracle UK: Announced film was completed, being coloured in Paris[25] 9 December 1912

- Das Mirakel UK: Announced private screening of Das Mirakel as The Miracle at the Shaftesbury Pavilion (prop. Isaac Davis and his Electric Pavilions inc. Ritzy Cinema and Hammersmith Apollo), week of 9 December.

- Das Mirakel UK: On 12 December 1912, the Shaftesbury Feature Film Company Ltd, 55-59 Shaftesbury Avenue, was formed with capital of £1,125 (£1 shares) to take over the UK distribution of 10 films by Continental Kunstfilm from Elite Sales Agency Ltd. (SFFC ceased trading 13 July 1914.) David Beck was a director of both firms.[26]

- Das Mirakel US: The film received its US general public première at the Hyperion Theatre, New Haven, Conn. on 15 December 1912.[27][note 1]

- The Miracle UK: Seeks court injunction to prevent Conti/SFFCo from showing their film. Court case 16–17 December 1912, Menchen v. Elite Sales Agency. The judge couldn't rule on the copyright, but allowed the film to be shown under another name. He suggested that Das Mirakel be shown under the name 'Sister Beatrice'.[28][29][5][30] The Shaftesbury Feature Film Co. released it that day as Sister Beatrix, a few days before Menchen's film.

- UK showings

- Das Mirakel UK: Première of the Continental film as the 3-reeler Sister Beatrix at the Shaftesbury Pavilion to a "storm of applause" on 17 December 1912, the same day as the injunction was granted.[31]

- The Miracle UK: Première of The Miracle (1912 film) in full colour, with orchestra, chorus and live actors at Covent Garden, 21 December 1912.

- Das Mirakel UK: The Shaftesbury Feature Film Co arranged a number of single showings of Sister Beatrix around the UK, but these were one-offs, not regular scheduled performances, typically being shown at 11 a. m.[32]

- The Office of the Cinematograph Trading Co., Ltd., Metropole Buildings, The Hayes, Cardiff, 11 a.m., Monday, 13 January

- The Office of Messrs. The Walturdaw Co., Ltd., 192, Corporation Street, Birmingham, 11 a.m., Wednesday, 15 January

- The Office of The New Century Film Service, 2-4, Quebec Street, Leeds. 11 a.m., Friday, 17 January

- Manchester. Monday, 20 January Please communicate for time and place.

- By arrangement with Films, Ltd., of Manchester Road, Liverpool: The Electra Theatre, London Road, Liverpool, 11 a.m., Tuesday, 21 January.

- By arrangement with Henderson's film Bureau, Irving House, Newcastle-on-Tyne: The Royal Electric Theatre, Great Market, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Thursday, 12 noon, 23 January.

- The Miracle UK: The Miracle transferred to the Picture House Oxford Street, (junc. Poland St) on Friday 24 January 1913 after a month at the Royal Opera House, where it had still been showing three times daily (3, 6.30 and 9pm) with chorus and orchestra of 200 singers for as little as sixpence.[33]

- The Miracle UK: The Miracle was booked for 72 towns in the United Kingdom. "When the history of cinematography comes to be written it seems to me that "The Miracle" will have to be recorded as the record film."[34] "The Miracle has broken all records at Kings's Hall, Leyton, Curzon Hall, Birmingham, Royal Electric Theatre, Coventry and the Popular Picture Palace, Gravesend."[35][note 2]

- Das Mirakel UK: The Shaftesbury Feature Film Co.'s Sister Beatrix advertisement for Easter week (March 23) read: "We have two copies vacant for Easter week. Bookings allocated in strict rotation". Easter Sunday 1913 was 23 March.[36] By contrast there were 90 copies of Menchen's film being exhibited throughout the UK to capacity audiences.[37]

- The Miracle UK: Menchen's full-page advertisement after Easter (March 23) read: "The Easter Triumph. Max Reinhardt's wordless Lyricscope play / The Miracle. Nothing like it ever presented. Re-booked everywhere. A marvellous box office magnet."[38]

Mirakel in the USA

In the USA the film faced legal opposition from Albert H. Woods, the owner of rights to and distributor of the 'official' film of Max Reinhardt's The Miracle: the battle ended in a temporary injunction against its distributors, the New York Film Company, from leasing the Continental film under the title of The Miracle.

After court cases involving the rival version made by Joseph Menchen, the Continental version distributed by the New York Film Co. was known (after 22 March 1913 at the latest) as Sister Beatrice in the USA.[39] The name change to Sister Beatrice was suggested by a judge during a similar copyright court case in London.[40][5]

The film's UK distributor, Elite Sales Co., ceased trading in October 1913, citing heavy losses.

Critical Reaction

A review by an anonymous critic in Billboard of Misu's 4-reel film, after a press showing at 9 a.m., Friday 18 October 1913: "Like most European productions so much emphasis ls placed on the ensemble numbers and on the settings that the whole play is staged at a distance from the camera. Facial expressions are therefore not vivid or intense, although discernable and good considering the conditions." [21]

The critic W. Stephen Bush[note 3] thought the film good enough to use in a lecture about the use of film in teaching history.

In the lecture room of the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences, before a distinguished audience of educators headed by Professor Franklin Hooper, one of the best known pedagogues of the country, a special exhibition of the films [sic][41] known as "The Miracle" was given a few days ago. The picture was shown primarily to demonstrate the high and unique teaching power of the cinematograph and its special fitness as an illustrator of history. Before the exhibition, Mr. W. Steven Bush, of The Moving Picture World, delivered an interesting lecture on the cinematograph as a most valuable teaching agent in history.[42]

The Miracle was shown in Baltimore and in Washington D. C. at Tom Moore's Garden Theater[note 4] to positive notices:

"The Miracle the well-known four-reel production of the German Art Film Society, was exhibited in Baltimore at Albaugh's Theater in the week ending January 6th 1913. The attendance was good and the presentation of the films very creditable. An orchestra of twelve pieces rendered the special musical score, which had been prepared by Mr. E. Luz. Mr. Louis Bache, formerly assistant manager of the Electric Theater Supply Company and recently connected in a prominent way with the General Film Company of Philadelphia, had charge of the projection and his skillful work elicited praise from the press and the public. Prices ranged from 25 cents to one dollar."[43]

"The Miracle, the four-reel feature of the German Art Film Company, had a sensational run at Tom Moore's Garden Theater at Washington, D. C. The reels had been hired for three days, but the crowds came so fast that the engagement was extended to a whole week."[44]

German premières

On 13 May 1914 Max Reinhardt's original spectacular stage production of Karl Vollmoeller's pantomime The Miracle ended its Europe-wide run in Berlin at the Circus Busch, a purpose-built indoor circus arena.

Das Marienwunder: eine alte legende remained banned in Germany until some time in May 1914, when the film was re-classified as over 18 only (jugendverbot) by the Berlin police censor and released with cuts.[45]

The Miracle (as Das Mirakel) received its German première on Monday, 15 May 1914 at the Palast am Zoo cinema (later Ufa-Palast am Zoo), Charlottenburg, Berlin, with full score by Engelbert Humperdinck, full orchestra and chorus, church bells and processions of actors.[46]

See also

- The Miracle (play)

- The Miracle (1912 film)

- The Miracle (1959 film)

- List of films made by Continental-Kunstfilm

References

- Notes

- ↑ NB Lengthy assorted notes on Hyperion Theatre

- "The Moving Picture World of October 4, 1912, reported that the Hyperion Theatre had begun its final season as a legitimate house. It was to be operated by the Shuberts until May 1, 1914, when the lease would expire, and then be taken over by S. Z. Poli, to be operated as a movie and vaudeville house (the new Shubert Theatre opened in 1914.) The Hyperion’s career as a stage house was not entirely over, though, as I’ve found references to a repertory season being presented there by Poli in 1920."

- Manager at some point was E. D. Eldridge.

- The Hyperion Theatre was not located on the campus of Yale as many people believe. It was a commercial theatre in New Haven that various Yale organizations used for performances before the University Theatre opened in 1927.

The Hyperion opened in 1880 as Carll's Opera House, and became the Hyperion in 1897. It was owned around this time, by George Bunnell, who also owned the New Haven Grand Opera House. The Hyperion burned in November 1921 with 4 dead and 80 injured, (source: New York Times 28 November 1921) and later became the College Street Theatre (a movie house) in the mid-1930's and Loew's College Theatre. It closed in the mid-1970's and was demolished in 1998. The location is now a parking lot. (Source: Hyperion Theatre at Cigar Label Junkie) - Hyperion known as the Poli-College after its owner S. Z. Poli.

- Pic of interior - BoxOffice Magazine 7 August 1961.

- ↑

- King's Hall, Leyton at CinemaTreasures.org was later taken over by Clavering & Rose, possibly related to the Clavering who was a director of Elite Sales Agency, or one of his brothers.

- The first cinema shows in Birmingham had been presented in the Curzon Hall, Suffolk Street, a hall originally designed in 1864 for dog shows. It held 3,000 people. Its proprietor, Walter Jeffs, had originally included films as a subsidiary part of a show: in time, they became the main attraction. In 1915 it became known as the West End Cinema. Source: 'Economic and Social History: Social History since 1815'. A History of the County of Warwick: Volume 7: The City of Birmingham (1964), pp. 223-245. Accessed: 21 December 2012

- Popular Picture Palace: see 'Super Cinema' at Cinema Treasures

- ↑ For more information on W. Stephen Bush, see "The Moving Picture World of W. Stephen Bush", Film History Vol. 2 No. 1, Winter 1988 (JSTOR)

- ↑ See Central Theatre and Shubert Theatre at CinemaTreasures.org.

Tom Moore's Garden Theater was at 425-433 9th Street NW, Washington, DC 20004. Originally opened as Imperial Theatre on 20 November 1911, then taken over by Tom Moore in 1913. In 1922 its new owner Henry Crandall re-opened it as the Central Theatre on 21 December 1922. The Crandall theatres were taken over by the Stanley organisation who in turn were merged into the Warner Bros. Circuit Management.

When the old Gayety theatre at 513 9th Street NW, was taken over by the Shuberts to show serious plays, the name and burlesque style of entertainment was transferred to the Central, which became the Gayety Theatre until it closed and was demolished in 1973.

- Citations

- ↑ Film-Kurier, 2 March 1921 (in German)

- ↑ Cinema News & Property Journal, 1 January 1913, pp. 43-45

- ↑ Carter 1914, p. 140.

- ↑ Heisterbach 1851, pp. 42–43 (pdf p. 52), De Beatrice custode, Book VII, Ch. XXXIV

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 'The Stage' Year Book 1913, pp. 293–294.

- ↑ New York Dramatic Mirror, 16 February 1897

- ↑ Lamprecht 1969, p. 187.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lehmann & von Wendrin 1997, p. 46.

- ↑ "The makers of the New York Film Company's production have secured exclusive rights in Germany, although the film has been forbidden to be shown by the Government on account of the subject being strongly argumentative for the Catholic Church." "Fight over 'Miracle'". The Billboard, 19 October 1912, p. 14, col. 3. The article also mentions the laxness of copyright law in the US.

- ↑ Moving Picture World Vol. 12, No. 8, 25 May 1912, page 869 (Volume starts p. 700)

- ↑ MPW 1912b, p. 871 Vol. 12 No. 8, 25 May 1912

- ↑ The Cinema News and Property Gazette Vol. 1, November 1912, p. 25

- ↑ MPW 1912c, p. 89 Vol 13 No. 1, 6 July 1912)

- ↑ London Project

- ↑ P'dorf Rundschau 2006, pp. 4–5.

- ↑ MPW 1912c, p. 89.

- ↑ The Billboard, 16 November 1912, p. 55

- ↑ Frohlich & Schwab 1918, pp. 412–415, 640–644.

- ↑ New York Dramatic Mirror, 12 March 1913, p. 30, col. 2

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Billboard, 16 November 1912, p. 55.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Billboard, 19 October 1913.

- ↑ Mirakel at filmportal.de

- ↑ Library of Congress. Copyright Office 1912, p. 598.

- ↑ The Cinema News & Property Gazette, Volume I, 5 November 1912, p.17

- ↑ "Film show in Covent Garden", New York Times, 9 December 1912.]

- ↑ "Shaftsbury Feature Film Co Ltd" entry at The London Project

- ↑ "Alleged Miracle piracy", Variety, XXIX:13, 28 February 1913, p. 15, col. 3

- ↑ Copinger 1915, p. 69n.

- ↑ MPW 1913a, p. 146 4 January 1913. Vol. 15, no. 1.

- ↑ The Times, 18 December 1912.

- ↑ Cinema News 1913, p. 1 January, p. 45.

- ↑ The Cinema News and Property Gazette Vol. II, 8 January 1913, p. 15

- ↑ The Cinema News & Property Gazette, Number 13, Volume II (New series) 29 January 1913, pp 21 & 42 (pdf pp. 413 & 434)

- ↑ The Cinema News & Property Gazette, Number 13, Vol. II, 22 January 1913, p. 7, pdf p.303

- ↑ The Cinema News & Property Gazette, Number 13, Volume II (New series) 26 February 1913, p. 29, pdf p. 809

- ↑ The Cinema News and Property Gazette Vol. 2, 5 March 1913, p. 14

- ↑ The Cinema News and Property Gazette, Vol. 2, 12 March 1913, p. 3 (pdf p. 999)

- ↑ The Cinema News and Property Gazette, Vol. 2, 26 March 1913, p. 26

- ↑ Woods obtained an injunction to stop NYFC selling pictures representing The Miracle. Motion Picture World, 15:12, 22 March 1913 ((MPW 1913a, p. 1232))

- ↑ MPW 1913a, p. 1281.

- ↑ The review is dated 7 December 1912, before Menchen's film received its première in London, so "films" may well mean the four separate reels.

- ↑ MPW 1912d, p. 959 7 December 1912

- ↑ MPW 1913a, p. 441

- ↑ MPW 1913a, p. 685

- ↑ Mirakel at filmportal.de

- ↑ Lichtbild-Bühne, Nr. 26, 16 May 1914 (in German) at filmportal.de Certain (translated) phrases from the hand of one Jos. Menchen can be detected in this purple prose.

- Sources

- Birett, Herbert (1980). Verzeichnis in Deutschland gelaufener Filme 1911-1920 (in German). Munich. ISBN 3-598-10067-1.

- Bottomore, Stephen (2000). The Titanic and Silent Cinema. Volume 9 in a series of monographs on pre-cinema and early fiction. The Projection Box. ISBN 978-1903000-00-7.

- Carter, Huntly (1914). The Theatre of Max Reinhardt. New York: Mitchell Kennerley.

- "The Cinema News and Property Gazette". 1912.

- "The Cinema News and Property Gazette". 1913.

- Copinger, Walter Arthur (1915). Easton, J. M., ed. The law of copyright, in works of literature, art, architecture, photography, music and the drama : including chapters on mechanical contrivances and cinematographs: together with international and foreign copyright, with the statutes relating thereto (5th ed.). London: Stevens and Haynes. p. 69n.

- Frohlich, Louis D.; Schwab, Charles (1918). The law of motion pictures including the law of the theatre. New York: Baker, Voorhis and Co.

- Heisterbach, Caesar of (1851). Strange, Joseph, ed. Dialogus miraculorum, vol. II (in Latin). Cologne, Bonn and Brussels: J. M. Heberle (H. Lempertz & Co.). (See also Volume I)

- Lamprecht, Gerhard (1969). Deutsche Stummfilme 1903-1912 (in German). Berlin: Deutsche Kinemathek e.V.

- Lehmann, Kirsten; von Wendrin, Lydia Wiehring (1997). "Mime Misu - Der Regisseur des Titanic-Films In Nacht und Eis (D 1912)". Filmblatt (in German) (CineGraph Babelsberg e.V., Berlin-BrandenburgischesCentrum für Filmforschung) 2 (6, Winter 1997). ISSN 1433-2051.

- Library of Congress. Copyright Office (1912). Catalogue of copyright entries: Pamphlets, leaflets,... motion pictures, Volume 9, Issue 2. Washington, D.C.: Govt. Printing Office.

- "The Moving Picture World, July to September 1912" XIII. New York: Chalmers Publishing. 1912c.

- "The Moving Picture World, October to December 1912" XIV. New York: Chalmers Publishing. 1912d.

- "The Moving Picture World, January to March 1913" XV. New York: Chalmers Publishing. 1913a.

- "Winterwunder in Perchtoldsdorf" (PDF). Perchtoldsdorfer Rundschau (in German) (Marktgemeindeamt Perchtoldsdorf). December 2006. Retrieved 2012-06-23.

- 'The Stage' Year Book. 1913. pp. 293–294.

- Wedel, Michael (1999). "'Napoleon der Filmkunst' oder: Der amerikanische Bluff. Neuigkeitenzur Biographie von Mime Misu". Filmblatt (in German) (CineGraph Babelsberg e.V., Berlin-Brandenburgisches Centrum für Filmforschung) 4 (9, Winter 1998–1999). ISSN 1433-2051.