Dark Ages (historiography)

The Dark Ages is a historical periodization used originally for the Middle Ages, which emphasizes the cultural and economic deterioration that supposedly occurred in Western Europe following the decline of the Roman Empire.[1][2] The label employs traditional light-versus-darkness imagery to contrast the "darkness" of the period with earlier and later periods of "light".[3] The period is characterized by a relative scarcity of historical and other written records at least for some areas of Europe, rendering it obscure to historians. The term "Dark Age" derives from the Latin saeculum obscurum, originally applied by Caesar Baronius in 1602 to a tumultuous period in the 10th and 11th centuries.[4]

The term once characterized the bulk of the Middle Ages, or roughly the 6th to 13th centuries, as a period of intellectual darkness between extinguishing the "light of Rome" after the end of Late Antiquity, and the rise of the Italian Renaissance in the 14th century.[3][5] This definition is still found in popular use,[1][2][6] but increased recognition of the accomplishments of the Middle Ages has led to the label being restricted in application. Since the 20th century, it is frequently applied to the earlier part of the era, the Early Middle Ages (c. 5th–10th century).[7][8] However, many modern scholars who study the era tend to avoid the term altogether for its negative connotations, finding it misleading and inaccurate for any part of the Middle Ages.[9][10][11]

The concept of a Dark Age originated with the Italian scholar Petrarch (Francesco Petrarca) in the 1330s, and was originally intended as a sweeping criticism of the character of Late Latin literature.[3][12] Petrarch regarded the post-Roman centuries as "dark" compared to the light of classical antiquity. Later historians expanded the term to refer to the transitional period between Roman times and the High Middle Ages (c. 11th–13th century), including the lack of Latin literature, and a lack of contemporary written history, general demographic decline, limited building activity and material cultural achievements in general. Later historians and writers picked up the concept, and popular culture has further expanded on it as a vehicle to depict the early Middle Ages as a time of backwardness, extending its pejorative use and expanding its scope.[13]

History

The term "Dark Ages" originally was intended to denote the entire period between the fall of Rome and the Renaissance; the term "Middle Ages" has a similar motivation, implying an intermediate period between Classical Antiquity and the Modern era. In the 19th century scholars began to recognize the accomplishments made during the period, thereby challenging the image of the Middle Ages as a time of darkness and decay.[6] Now the term is not used by scholars to refer to the entire medieval period;[10] when used, it is generally restricted to the Early Middle Ages.[1]

The rise of archaeology and other specialties in the 20th century has shed much light on the period and offered a more nuanced understanding of its positive developments.[13] Other terms of periodization have come to the fore: Late Antiquity, the Early Middle Ages, and the Great Migrations, depending on which aspects of culture are being emphasized. When modern scholarly study of the Middle Ages arose in the 19th century, the term "Dark Ages" was at first kept, with all its critical overtones. On the rare occasions when the term "Dark Ages" is used by historians today, it is intended to be neutral, namely, to express the idea that the events of the period often seem "dark" because of the scarcity of artistic and cultural output,[14] including historical records, when compared with both earlier and later times.[10]

Petrarch

The idea of a Dark Age originated with Petrarch in the 1330s.[3][6] Writing of those who had come before him, he said: "Amidst the errors there shone forth men of genius; no less keen were their eyes, although they were surrounded by darkness and dense gloom".[15] Christian writers, including Petrarch himself,[3] had long used traditional metaphors of "light versus darkness" to describe "good versus evil". Petrarch was the first to co-opt the metaphor and give it secular meaning by reversing its application. Classical Antiquity, so long considered the "dark" age for its lack of Christianity, was now seen by Petrarch as the age of "light" because of its cultural achievements, while Petrarch's time, allegedly lacking such cultural achievements, was seen as the age of darkness.[3]

As an Italian, Petrarch saw the Roman Empire and the classical period as expressions of Italian greatness.[3] He spent much of his time travelling through Europe rediscovering and republishing classic Latin and Greek texts. He wanted to restore the classical Latin language to its former purity. Humanists saw the preceding 900-year period as a time of stagnation. They saw history unfolding, not along the religious outline of Saint Augustine's Six Ages of the World, but in cultural (or secular) terms through the progressive developments of classical ideals, literature, and art.

Petrarch wrote that history had two periods: the classic period of the Greeks and Romans, followed by a time of darkness, in which he saw himself as still living. In around 1343, in the conclusion to his epic Africa, he wrote: "My fate is to live among varied and confusing storms. But for you perhaps, if as I hope and wish you will live long after me, there will follow a better age. This sleep of forgetfulness will not last for ever. When the darkness has been dispersed, our descendants can come again in the former pure radiance."[16] In the 15th century, historians Leonardo Bruni and Flavio Biondo developed a three tier outline of history. They used Petrarch's two ages, plus a modern, "better age", which they believed the world had entered. The term "Middle Ages," in Latin media tempestas (1469) or medium aevum (1604), was later used to describe the period of supposed decline.[17]

Reformation

During the Protestant Reformation of the 16th and 17th centuries, Protestants wrote of the Middle Ages as a period of Catholic corruption. Just as Petrarch's writing was not an attack on Christianity per se — along with his humanism, he was deeply occupied with the search for God — neither was this an attack on Christianity: it was a drive to restore what Protestants saw as biblical Christianity.

The Magdeburg Centuries was a work of ecclesiastical history compiled by Lutheran scholars and published between 1559 and 1574. Devoting a volume to each century, it covered the first thirteen centuries of Christianity up to 1298. The work was virulently anti-Catholic. Identifying the Papacy as the Antichrist, it painted a "dark" picture of church history after the 5th century, characterizing it as "increments of errors and their corrupting influences".

Baronius

In response to the Protestants, Roman Catholics developed a counter-image, depicting the High Middle Ages in particular as a period of social and religious harmony, and not "dark" at all.[18] The most important Catholic reply to the Magdeburg Centuries was the Annales Ecclesiastici by Cardinal Caesar Baronius. Baronius was a trained historian who kept theology in the background and produced a work that the Encyclopædia Britannica in 1911 described as "far surpassing anything before his day"[19] and that Acton regarded as "the greatest history of the Church ever written".[20] The Annales, covering the first twelve centuries of Christianity up to 1198, was published in twelve volumes between 1588 and 1607. It was in Volume X that Baronius coined the term "dark age" for the period between the end of the Carolingian Empire in 888[21] and the first inklings of the Gregorian Reform under Pope Clement II in 1046:

The new age (saeculum) which was beginning, for its harshness and barrenness of good could well be called iron, for its baseness and abounding evil leaden, and moreover for its lack of writers (inopia scriptorum) dark (obscurum).[22]

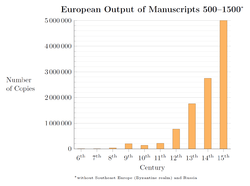

Significantly, Baronius termed the age "dark" because of the paucity of written records capable of throwing light on it for the historian. The "lack of writers" he referred to may be illustrated by comparing the number of volumes in Migne's Patrologia Latina containing the work of Latin writers from the 10th century (the heart of the age he called "dark") with the number of volumes containing the work of writers from the preceding and succeeding centuries. A minority of these writers were historians.

| Century | Migne Volume Nos | Volumes |

|---|---|---|

| 7th | 80–88 | 8 |

| 8th | 89–96 | 7 |

| 9th | 97–130 | 33 |

| 10th | 131–138 | 7 |

| 11th | 139–151 | 12 |

| 12th | 162–191 | 39 |

| 13th | 192–217 | 25 |

There is a sharp drop from 33 volumes in the 9th century to just 7 in the 10th. The 11th century, with 12 volumes, evidences a certain recovery, and the 12th century, with 39, surpasses the 9th, something the 13th, with just 25 volumes, fails to do. There was indeed a "dark age", in Baronius's sense of a "lack of writers", between the Carolingian Renaissance in the 9th century and the beginnings, some time in the 11th, of what has been called the Renaissance of the 12th century. Furthermore, besides the "dark age" named by Baronius, there was an earlier one, for regarding "lack of writers" the 7th and 8th centuries are pretty much on a par with the 10th. In short, in Western Europe during the 1st millennium, two "dark ages" can be identified, separated by the brilliant but all too brief Carolingian Renaissance.

Baronius's "dark age" seems to have struck historians as something they could use, for it was in the 17th century that the terms "dark age" and "dark ages" started to proliferate in the various European languages, with his original Latin term, "saeculum obscurum", being reserved for the period he had applied it to. But while some historians, following Baronius's lead, used "dark age" neutrally to refer to a dearth of written records, others, in the manner of the early humanists and Protestants (and later the Enlightenment writers and their successors right up to the present day) used it pejoratively, lapsing into that lack of neutrality and objectivity that has quite spoilt the term for many modern historians.

The first British historian to use the term was most likely Gilbert Burnet, in the form "darker ages", which appears several times in his work in the last quarter of the 17th century. His earliest use of it seems to have been in 1679 in the "Epistle Dedicatory" to Volume I of The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, where he writes: "The design of the reformation was to restore Christianity to what it was at first, and to purge it of those corruptions, with which it was overrun in the later and darker ages."[25] He uses it again in 1682 in Volume II of the History, where he dismisses the story of "St George's fighting with the dragon" as "a legend formed in the darker ages to support the humour of chivalry".[26] Burnet was a Protestant bishop chronicling how England became Protestant and his use of the term is invariably pejorative.

Enlightenment

During the 17th and 18th centuries, in the Age of Enlightenment, many critical thinkers saw religion as antithetical to reason. For them the Middle Ages, or "Age of Faith", was therefore the polar opposite of the Age of Reason.[27] Kant and Voltaire, among others, were vocal in attacking the religiously dominated Middle Ages as a period of social regress, while Gibbon in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire expressed contempt for the "rubbish of the Dark Ages".[28] Yet just as Petrarch, seeing himself on the threshold of a "new age", was criticizing the centuries until his own time, so too were the Enlightenment writers criticizing the centuries until their own. These extended well after Petrarch's time, since religious domination and conflict were still common into the 17th century and beyond, albeit diminished in scope.

Consequently, an evolution had occurred in at least three ways. Petrarch's original metaphor of light versus dark had been expanded in time, implicitly at least. Even if the early humanists after him no longer saw themselves living in a dark age, their times were still not light enough for 18th-century writers who saw themselves as living in the real Age of Enlightenment, while the period covered by their own condemnation had been stretched to include what we now call Early Modern times. Additionally, Petrarch's metaphor of darkness, which he used mainly to deplore what he saw as a lack of secular achievements, was sharpened to take on a more explicitly anti-religious and anti-clerical meaning.

In spite of this, the term "Middle Ages", used by Biondo and other early humanists after Petrarch, was the name in general use before the 18th century to denote the period until the Renaissance. The earliest recorded use of the English word "medieval" was in 1827. The concept of the Dark Ages was also in use, but by the 18th century, it tended to be confined to the earlier part of this medieval period. The earliest entry for a capitalised "Dark Ages" in the Oxford English Dictionary is a reference in Henry Thomas Buckle's History of Civilization in England in 1857.[1] Starting and ending dates varied: the Dark Ages were considered by some to start in 410, by others in 476 when there was no longer an emperor in Rome, and to end about 800, at the time of the Carolingian Renaissance under Charlemagne, or to extend through the rest of the 1st millennium.

Romanticism

In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, the Romantics reversed the negative assessment of Enlightenment critics and launched a vogue for medievalism.[29] The word "Gothic" had been a term of opprobrium akin to "Vandal" until a few self-confident mid-18th-century English "Goths" like Horace Walpole initiated the Gothic Revival in the arts. This sparked off an interest in the Middle Ages, which for the following Romantic generation began to take on an idyllic image of the "Age of Faith". This image, in reaction to a world dominated by Enlightenment rationalism in which reason trumped emotion, expressed a romantic view of a Golden Age of chivalry. The Middle Ages were seen with romantic nostalgia as a period of social and environmental harmony and spiritual inspiration, in contrast to the excesses of the French Revolution and, most of all, to the environmental and social upheavals and sterile utilitarianism of the emerging industrial revolution.[30] The Romantics' view of these earlier centuries can still be seen in modern-day fairs and festivals celebrating the period with costumes and events.

Just as Petrarch had turned the meaning of light versus darkness, so had the Romantics turned the judgment of Enlightenment critics. However, the period idealized by the Romantics focused largely on what is now known as the High Middle Ages, extending into Early Modern times. In one respect, this was a reversal of the religious aspect of Petrarch's judgment, since these later centuries were those when the universal power and prestige of the Church was at its height. To many users of the term, the scope of the Dark Ages was becoming divorced from this period, denoting mainly the earlier centuries after the fall of Rome.

Modern academic use

In the 19th century, the term "Dark Ages" was widely used by historians. In 1860, in The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, Jacob Burckhardt delineated the contrast between the "dark ages" of the medieval period and the more enlightened period of the Renaissance, which had revived the cultural and intellectual achievements of antiquity.[31] However, the early 20th century saw a radical re-evaluation of the Middle Ages, and with it a calling into question of the terminology of darkness,[10] or at least of its pejorative use. Historian Denys Hay exemplified this when he spoke ironically of "the lively centuries which we call dark".[32]

When the term "Dark Ages" is used by historians today, therefore, it is intended to be neutral, namely, to express the idea that the events of the period often seem "dark" to us because of the paucity of historical records compared with both earlier and later times.[10] The term is used in this sense (often in the singular) to reference the Bronze Age collapse and the subsequent Greek Dark Ages,[1] the dark ages of Cambodia (c. 1450-1863), and also a hypothetical Digital Dark Age which would ensue if the electronic documents produced in the current period were to become unreadable at some point in the future.[33] Some Byzantinists have used the term "Byzantine Dark Ages" to refer to the period from the earliest Muslim conquests to about 800,[34] because there are no extant historical texts in Greek from this period, and thus the history of the Byzantine Empire and formerly Byzantine territories that were conquered by the Muslims is poorly understood and must be reconstructed from other types of contemporaneous sources, such as religious texts.[35] It is also known that very few Greek manuscripts were copied in this period, indicating that the 7th and 8th centuries, which were a period of crisis for the Byzantines because of the Muslim conquests, were also less intellectually active than other periods.[36] The term "dark age" is not restricted to the discipline of history. Since the archaeological evidence for some periods is abundant and for others scanty, there are also archaeological dark ages.[37]

Since the Late Middle Ages significantly overlap with the Renaissance, the term "Dark Ages" has become restricted to distinct times and places in medieval Europe. Thus the 5th and 6th centuries in Britain, at the height of the Saxon invasions, have been called "the darkest of the Dark Ages",[38] in view of the societal collapse that characterized the period and the consequent lack of historical records compared with either the Roman era before or the centuries that followed. Further south and east, the same was true in the formerly Roman province of Dacia, where history after the Roman withdrawal went unrecorded for centuries as Slavs, Avars, Bulgars, and others struggled for supremacy in the Danube basin, and events there are still disputed. However, at this time the Arab Empire is often considered to have experienced its Golden Age rather than Dark Age; consequently, this usage of the term must also differentiate geographically. While Petrarch's concept of a Dark Age corresponded to a mostly Christian period following pre-Christian Rome, the use of the term today applies mainly to those cultures and periods in Europe least Christianized and thus most sparsely covered by chronicles and other contemporary sources, nearly all written by Catholic clergy at this date.

However, from the mid-20th century onwards, other historians became critical of even this nonjudgmental use of the term for two main reasons.[10] First, it is questionable whether it is possible to use the term "Dark Ages" effectively in a neutral way; scholars may intend this, but it does not mean that ordinary readers will so understand it. Second, the explosion of new knowledge and insight into the history and culture of the Early Middle Ages, which 20th-century scholarship has achieved,[39] means that these centuries are no longer dark even in the sense of "unknown to us". To avoid the value judgment implied by the expression, many historians avoid it altogether.[40]

Historians who use the term usually flag it as incorrect. A recently published history of German literature describes "the dark ages" as "a popular if ignorant manner of speaking" about "the mediaeval period", but then immediately (in the next sentence) goes on to use the term "dark age" to mean "little studied."[41]

Modern popular use

Rational thought and the study of nature

The medieval period is frequently caricatured as supposedly a "time of ignorance and superstition" which placed "the word of religious authorities over personal experience and rational activity."[42] However, rationality was increasingly held in high regard as the Middle Ages progressed. The historian of science Edward Grant, writes that "If revolutionary rational thoughts were expressed [in the 18th century], they were made possible because of the long medieval tradition that established the use of reason as one of the most important of human activities".[43] Furthermore, David Lindberg says that, contrary to common belief, "the late medieval scholar rarely experienced the coercive power of the church and would have regarded himself as free (particularly in the natural sciences) to follow reason and observation wherever they led".[44]

The caricature of the period is also reflected in a number of more specific notions. For instance, a claim that was first propagated in the 19th century[45][46] and is still very common in popular culture is the supposition that all people in the Middle Ages believed that the Earth was flat. This claim is mistaken.[46][47] In fact, lecturers in the medieval universities commonly advanced evidence in favor of the idea that the Earth was a sphere.[48] Lindberg and Ronald Numbers write: "There was scarcely a Christian scholar of the Middle Ages who did not acknowledge [Earth's] sphericity and even know its approximate circumference".[49]

Other misconceptions such as: "the Church prohibited autopsies and dissections during the Middle Ages", "the rise of Christianity killed off ancient science", and "the medieval Christian church suppressed the growth of natural philosophy", are all cited by Ronald Numbers as examples of widely popular myths that still pass as historical truth, although they are not supported by current historical research.[50] They help maintain the idea of a "Dark Age" spanning through the medieval period.

Unlike pagan Rome, Christian Europe did not exercise a universal prohibition of the dissection and autopsy of the human body and some examinations were carried out from at least the 13th century [51][52][53] It has even been suggested by a modern Jesuit scholar that the Christian theology contributed significantly to the revival of human dissection and autopsy by providing a new socio-religious and cultural context in which the human cadaver was no longer seen as sacrosanct.[51]

See also

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Oxford English Dictionary (2 ed.). Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. 1989.

a term sometimes applied to the period of the Middle Ages to mark the intellectual darkness characteristic of the time; often restricted to the early period of the Middle Ages, between the time of the fall of Rome and the appearance of vernacular written documents.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Dark age" in Merriam-Webster

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 Mommsen, Theodore (1942). "Petrarch's Conception of the 'Dark Ages'". Speculum (Cambridge MA: Medieval Academy of America) 17 (2): 226–242. doi:10.2307/2856364. JSTOR 2856364.

- ↑ Dwyer, John C., Church history: twenty centuries of Catholic Christianity, (1998) p. 155.

Baronius, Caesar. Annales Ecclesiastici, Vol. X. Roma, 1602, p. 647 - ↑ Petrarca, De sui ipsius et multorum ignorantia, ed. M. Capelli (Paris, 1906), p. 45.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Franklin, James (1982). "The Renaissance Myth". Quadrant 26 (11): 51–60., for example. Franklin is a mathematician who is discussing popularly-held misconceptions about mathematics and science, such as that "Galileo revolutionised physics by dropping weights from the Leaning Tower of Pisa." From his perspective as a mathematician, he says that the Dark Ages were sometimes very real, citing Isadore of Seville's writing that a cylinder was 'a square figure with a semicircle on top'.

- ↑ Ker, W. P. (1904). The dark ages. New York: C. Scribner's Sons. Page 1. (cf. The Dark Ages and the Middle Ages — or the Middle Age — used to be the same; two names for the same period. But they have come to be distinguished, and the Dark Ages are now no more than the first part of the Middle Age, while the term mediaeval is often restricted to the later centuries, about 1100 to 1500, the age of chivalry, the time between the first Crusade and the Renaissance. This was not the old view, and it does not agree with the proper meaning of the name.)

- ↑ Syed Ziaur Rahman, Were the “Dark Ages” Really Dark?, Grey Matter (The Co-curricular Journal of Jawaharlal Nehru Medical College), Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh, 2003: 7-10

- ↑ Snyder, Christopher A. (1998). An Age of Tyrants: Britain and the Britons A.D. 400–600. University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press. pp. xiii–xiv. ISBN 0-271-01780-5.. In explaining his approach to writing the work, Snyder refers to the "so-called Dark Ages", noting that "Historians and archaeologists have never liked the label Dark Ages ... there are numerous indicators that these centuries were neither 'dark' nor 'barbarous' in comparison with other eras."

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Jordan, Chester William (2004). Dictionary of the Middle Ages, Supplement 1. Verdun, Kathleen, "Medievalism" pp. 389–397. Sections 'Victorian Medievalism', 'Nineteenth-Century Europe', 'Medievalism in America 1500–1900', 'The 20th Century'. Same volume, Freedman, Paul, "Medieval Studies", pp. 383–389.

- ↑ Raico, Ralph. "The European Miracle". Retrieved 14 August 2011. "The stereotype of the Middle Ages as 'the Dark Ages' fostered by Renaissance humanists and Enlightenment philosophes has, of course, long since been abandoned by scholars."

- ↑ Thompson, Bard (1996). Humanists and Reformers: A History of the Renaissance and Reformation. Grand Rapids, MI: Erdmans. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8028-6348-5.

Petrarch was the very first to speak of the Middle Ages as a 'dark age', one that separated him from the riches and pleasures of classical antiquity and that broke the connection between his own age and the civilization of the Greeks and the Romans.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Tainter, Joseph A.; Barker, Graeme (ed.) (1999). "Post Collapse Societies". Companion Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Abingdon, England: Routledge. p. 988. ISBN 0-415-06448-1.

- ↑ Clark, Kenneth (1969), Civilisation (BBC Books)

- ↑ Petrarch (1367). Apologia cuiusdam anonymi Galli calumnias (Defence against the calumnies of an anonymous Frenchman), in Petrarch, Opera Omnia, Basel, 1554, p. 1195. This quotation comes from the English translation of Mommsen's article, where the source is given in a footnote. Cf. also Marsh, D, ed., (2003), Invectives, Harvard University Press, p. 457.

- ↑ Petrarch (1343). Africa, IX, 451-7. This quotation comes from the English translation of Mommsen's article.

- ↑ Albrow, Martin, The global age: state and society beyond modernity (1997), p. 205.

- ↑ Daileader, Philip (2001). The High Middle Ages. The Teaching Company. ISBN 1-56585-827-1. "Catholics living during the Protestant Reformation were not going to take this assault lying down. They, too, turned to the study of the Middle Ages, going back to prove that, far from being a period of religious corruption, the Middle Ages were superior to the era of the Protestant Reformation, because the Middle Ages were free of the religious schisms and religious wars that were plaguing the 16th and 17th centuries."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 1911: "History"

- ↑ Lord Acton (1906). Lectures on Modern History, p. 121.

- ↑ Baronius's actual starting-point for the "dark age" was 900 (annus Redemptoris nongentesimus), but that was an arbitrary rounding off due mainly to his strictly annalistic approach. Later historians, e.g. Marco Porri in his Catholic History of the Church (Storia della Chiesa) or the Lutheran Christian Cyclopedia ("Saeculum Obscurum"), have tended to amend it to the more historically significant date of 888, often rounding it down further to 880. The first weeks of 888 witnessed both the final break-up of the Carolingian Empire and the death of its deposed ruler Charles the Fat. Unlike the end of the Carolingian Empire, however, the end of the Carolingian Renaissance cannot be precisely dated, and it was the latter development that was responsible for the "lack of writers" that Baronius, as a historian, found so irksome.

- ↑ Baronius, Caesar (1602). Annales Ecclesiastici, Vol. X. Roma, p. 647. "Novum incohatur saeculum quod, sua asperitate ac boni sterilitate ferreum, malique exudantis deformitate plumbeum, atque inopia scriptorum, appellari consuevit obscurum."

- ↑ Schaff, Philip (1882). History of the Christian Church, Vol. IV: Mediaeval Christianity, A.D. 570–1073, Ch. XIII, §138. "Prevailing Ignorance in the Western Church"

- ↑ Buringh, Eltjo; van Zanden, Jan Luiten: "Charting the “Rise of the West”: Manuscripts and Printed Books in Europe, A Long-Term Perspective from the Sixth through Eighteenth Centuries", The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 69, No. 2 (2009), pp. 409–445 (416, table 1)

- ↑ Burnet, Gilbert (1679). The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, Vol. I. Oxford, 1929, p. ii.

- ↑ Burnet, Gilbert (1682). The History of the Reformation of the Church of England, Vol. II. Oxford, 1829, p. 423. Burnet also uses the term in 1682 in The Abridgement of the History of the Reformation of the Church of England (2nd Edition, London, 1683, p. 52) and in 1687 in Travels through France, Italy, Germany and Switzerland (London, 1750, p. 257). The Oxford English Dictionary erroneously cites the last of these as the earliest recorded use of the term in English.

- ↑ Bartlett, Robert (2001). "Introduction: Perspectives on the Medieval World", in Medieval Panorama. ISBN 0-89236-642-7. "Disdain about the medieval past was especially forthright amongst the critical and rationalist thinkers of the Enlightenment. For them the Middle Ages epitomized the barbaric, priest-ridden world they were attempting to transform."

- ↑ Gibbon, Edward (1788). The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Vol. 6, Ch. XXXVII, paragraph 619.

- ↑ Alexander, Michael (2007). Medievalism: The Middle Ages in Modern England. Yale University Press.

- ↑ Chandler, Alice K. (1971). A Dream of Order: The Medieval Ideal in Nineteenth-Century English Literature. University of Nebraska Press, p. 4.

- ↑ Barber, John (2008). The Road from Eden: Studies in Christianity and Culture. Palo Alto, CA: Academica Press, p. 148, fn 3.

- ↑ Hay, Denys (1977). Annalists and Historians. London: Methuen, p. 50.

- ↑ 'Digital Dark Age' May Doom Some Data, Science Daily, October 29, 2008.

- ↑ Lemerle, Paul (1986). Byzantine Humanism, translated by Helen Lindsay and Ann Moffat. Canberra, p. 81-82.

- ↑ Whitby, Michael (1992). "Greek historical writing after Procopius" in Byzantine and Early Islamic Near East, ed. Averil Cameron and Lawrence I. Conrad, Princeton, p. 25-80.

- ↑ Lemerle, Paul (1986). Byzantine Humanism, translated by Helen Lindsay and Ann Moffat. Canberra, p. 81-84.

- ↑ Project: Exploring the Early Holocene Occupation of North-Central Anatolia: New Approaches for Studying Archaeological Dark Ages Period of Project: 09/2007-09/2011

- ↑ Cannon, John and Griffiths, Ralph (2000). The Oxford Illustrated History of the British Monarchy (Oxford Illustrated Histories), 2nd Revised edition. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press, p. 1. The first chapter opens with the sentence: "In the darkest of the Dark Ages, the fifth and sixth centuries, there were many kings in Britain but no kingdoms."

- ↑ Welch, Martin (1993). Discovering Anglo-Saxon England. University Park, PA: Penn State Press.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica "It is now rarely used by historians because of the value judgment it implies. Though sometimes taken to derive its meaning from the fact that little was then known about the period, the term's more usual and pejorative sense is of a period of intellectual darkness and barbarity."

- ↑ Dunphy, Graeme (2007). "Literary Transitions, 1300–1500: From Late Mediaeval to Early Modern" in: The Camden House History of German Literature vol IV: "Early Modern German Literature". The chapter opens with the words: "A popular if uninformed manner of speaking refers to the medieval period as "the dark ages." If there is a dark age in the literary history of Germany, however, it is the one that follows: the fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, the time between the Middle High German Blütezeit and the full blossoming of the Renaissance. it may be called a dark age, not because literary production waned in these decades, but because nineteenth-century aesthetics and twentieth-century university curricula allowed the achievements of that time to fade into obscurity."

- ↑ David C. Lindberg, "The Medieval Church Encounters the Classical Tradition: Saint Augustine, Roger Bacon, and the Handmaiden Metaphor", in David C. Lindberg and Ronald L. Numbers, ed. When Science & Christianity Meet, (Chicago: University of Chicago Pr., 2003), p.8

- ↑ Edward Grant. God and Reason in the Middle Ages, Cambridge 2001, p. 9.

- ↑ quoted in the essay of Ted Peters about Science and Religion at "Lindsay Jones (editor in chief). Encyclopedia of Religion, Second Edition. Thomson Gale. 2005. p.8182"

- ↑ Historian Jeffrey Burton Russell, in his book Inventing the Flat Earth "... shows how nineteenth-century anti-Christians invented and spread the falsehood that educated people in the Middle Ages believed that the earth was flat" Russell's summary of his book

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Russell, Jeffey Burton (1991). Inventing the Flat Earth—Columbus and Modern Historians. Westport, CT: Praeger. pp. 49–58. ISBN 0-275-95904-X.

- ↑ A recent study of medieval concepts of the sphericity of the Earth notes that "since the eighth century, no cosmographer worthy of note has called into question the sphericity of the Earth." Klaus Anselm Vogel, "Sphaera terrae - das mittelalterliche Bild der Erde und die kosmographische Revolution", PhD dissertation, Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, 1995, p. 19

- ↑ E. Grant, Planets. Stars, & Orbs: The Medieval Cosmos, 1200-1687, (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Pr., 1994), pp. 626-630.

- ↑ Lindberg, David C.; Numbers, Ronald L. (1986). "Beyond War and Peace: A Reappraisal of the Encounter between Christianity and Science". Church History (Cambridge University Press) 55 (3): 338–354. doi:10.2307/3166822. JSTOR 3166822.

- ↑ Ronald Numbers (Lecturer) (May 11, 2006). Myths and Truths in Science and Religion: A historical perspective (Video Lecture). University of Cambridge (Howard Building, Downing College): The Faraday Institute for Science and Religion.

- ↑ 51.0 51.1 P Prioreschi, Determinants of the revival of dissection of the human body in the Middle Ages', Medical Hypotheses (2001) 56(2), 229–234)

- ↑ 'In the 13th century, the realisation that human anatomy could best be taught by dissection of the human body resulted in its legalisation of publicly dissecting criminals in some European countries between 1283 and 1365' - this was, however, still contrary to the edicts of the Church. Philip Cheung 'Public Trust in Medical Research?.', (2007), page 36

- ↑ 'Indeed, very early in the thirteenth century, a religious official, namely, Pope Innocent III (1198-1216), ordered the postmortem autopsy of a person whose death was suspicious', Toby Huff, 'The Rise Of Modern Science' (2003), page 195

Bibliography

- Wells, Peter S. (2008-07-14). Barbarians to Angels: The Dark Ages Reconsidered. W. W. Norton. p. 256. ISBN 0-393-06075-6.

- López, Robert Sabatino (1959). The Tenth Century: How Dark the Dark Ages?. Rinehart. p. 58.

- Herbermann, Charles G. "The Myths of the 'Dark' Ages," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XIII, 1888.

- Magevney, Eugene. "Christian Education in the 'Dark Ages'," The American Catholic Quarterly Review, Vol. XXIII, January/October 1898.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Dark Ages |

- "Dark Ages" in Encyclopædia Britannica Online.

- "Decline and fall of the Roman myth" by Terry Jones.

- "Why the Middle Ages are called the Dark Ages".

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||